Dakota people

The Dakota (pronounced [daˈkˣota], Dakota language: Dakȟóta/Dakhóta) are a Native American tribe and First Nations band government in North America. They compose two of the three main subcultures of the Sioux people, and are typically divided into the Eastern Dakota and the Western Dakota.

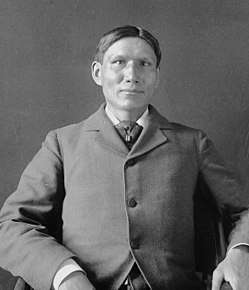

Charles Alex Eastman (1858–1939), physician, author, and co-founder of the Boy Scouts of America | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 20,460 (2010)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Dakota,[1] English | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (incl. syncretistic forms), traditional tribal religion, Native American Church, Wocekiye | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Lakota, Assiniboine, Stoney (Nakota), and other Sioux |

The Eastern Dakota are the Santee (Isáŋyathi or Isáŋ-athi; "knife" + "encampment", ″dwells at the place of knife flint″), who reside in the eastern Dakotas, central Minnesota and northern Iowa. They have federally recognized tribes established in several places.

The Western Dakota are the Yankton, and the Yanktonai (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ and Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna; "Village-at-the-end" and "Little village-at-the-end"), who reside in the Upper Missouri River area. The Yankton-Yanktonai are collectively also referred to by the endonym Wičhíyena (″Those Who Speak Like Men″). They also have distinct federally recognized tribes.

In the past the Western Dakota have been erroneously classified as Nakota, a branch of the Sioux who moved further west. The latter are now located in Montana and across the border in Canada, where they are known as Stoney.[2]

Name

The word Dakota means "ally" in the Dakota language, and their autonyms include Ikčé Wičhášta ("Indian people") and Dakhóta Oyáte ("Dakota people").[3]

History

Before the 17th century, the Santee Dakota (Isáŋyathi; "Knife" also known as the Eastern Dakota) lived around Lake Superior with territories in present-day northern Minnesota and Wisconsin. They gathered wild rice, hunted woodland animals and used canoes to fish. Wars with the Ojibwe throughout the 1700s pushed the Dakota into southern Minnesota, where the Western Dakota (Yankton, Yanktonai) and Teton (Lakota) were residing. In the 1800s, the Dakota signed treaties with the United States, ceding much of their land in Minnesota. Failure of the United States to make treaty payments on time, as well as low food supplies, led to the Dakota War of 1862, which resulted in the Dakota being exiled from Minnesota to numerous reservations in Nebraska, North and South Dakota and Canada. After 1870, the Dakota people began to return to Minnesota, creating the present-day reservations in the state.

The Yankton and Yanktonai Dakota (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ and Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna; "Village-at-the-end" and "Little village-at-the-end"), collectively also referred to by the endonym Wičhíyena, resided in the Minnesota River area before ceding their land and moving to South Dakota in 1858. Despite ceding their lands, their treaty with the U.S. government allowed them to maintain their traditional role in the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ as the caretakers of the Pipestone Quarry, which is the cultural center of the Sioux people. They are considered to be the Western Dakota (also called middle Sioux), and have in the past been erroneously classified as Nakota.[4] The actual Nakota are the Assiniboine and Stoney of Western Canada and Montana.

Ethnic groups

The Eastern and Western Dakota are two of the three groupings belonging to the Sioux nation (also called Dakota in a broad sense), the third being the Lakota (Thítȟuŋwaŋ or Teton). The three groupings speak dialects that are still relatively mutually intelligible. This is referred to as a common language, Dakota-Lakota, or Sioux.[5]

The other two languages of the Dakotan dialect continuum, Assiniboine and Stoney (spoken by the Nakota or Nakoda peoples), have grown widely or completely unintelligible to Dakota and Lakota speakers.[6]

The Dakota include the following bands:

- Santee division (Eastern Dakota) (Isáŋyathi, meaning "knife camp"[3])[6]

- Mdewakanton (Bdewékhaŋthuŋwaŋ "Spirit Lake Village" or "people of the mystic lake"[3])[6]

- notable persons: Taoyateduta

- Sisseton (Sisíthuŋwaŋ, translating to "swamp/lake/fish scale village"[3])

- Wahpekute (Waȟpékhute, "Leaf Archers")[6]

- notable persons: Inkpaduta

- Wahpeton (Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ, "Leaf Village")[6]

- Mdewakanton (Bdewékhaŋthuŋwaŋ "Spirit Lake Village" or "people of the mystic lake"[3])[6]

- Yankton-Yanktonai division (Western Dakota) (Wičhíyena)

Santee (Isáŋyathi or Eastern Dakota)

The Santee migrated north and westward from the Southeast United States, first into Ohio, then to Minnesota. Some came up from the Santee River and Lake Marion, area of South Carolina. The Santee River was named after them, and some of their ancestors' ancient earthwork mounds have survived along the portion of the dammed-up river that forms Lake Marion. In the past, they were a Woodland people who thrived on hunting, fishing and farming.

Migrations of Ojibwe people from the east in the 17th and 18th centuries, with muskets supplied by the French and British, pushed the Dakota further into Minnesota and west and southward. The US gave the name "Dakota Territory" to the northern expanse west of the Mississippi River and up to its headwaters.[8]

In the 21st century, the majority of the Santee live on reservations, reserves, and communities in Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Canada. Some have moved to cities for more work opportunities.

After the Dakota War of 1862, the federal government expelled the Santee from Minnesota. Many were sent to Crow Creek Indian Reservation. In 1864 some from the Crow Creek Reservation were sent to St. Louis and then by boat up the Missouri River, ultimately to the Santee Sioux Reservation. The Bdewákaŋthuŋwaŋ (Mdewakanton) live predominantly at the Prairie Island and Shakopee reservations in Minnesota.

Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ-Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna (Yankton-Yanktonai or Western Dakota)

The Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ-Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna, also known by the anglicized spelling Yankton (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋ: "End village") and Yanktonai (Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna: "Little end village") divisions consist of two bands or two of the seven council fires. According to Nasunatanka and Matononpa in 1880, the Yanktonai are divided into two sub-groups known as the Upper Yanktonai and the Lower Yanktonai (Húŋkpathina).[8]

They were involved in quarrying pipestone. The Yankton-Yanktonai moved into northern Minnesota. In the 18th century, they were recorded as living in the Mankato (Maka To – Earth Blue/Blue Earth) region of southwestern Minnesota along the Blue Earth River.[9]

Most of the Yankton live on the Yankton Indian Reservation in southeastern South Dakota. Some Yankton live on the Lower Brule Indian Reservation and Crow Creek Reservation, which is also occupied by the Lower Yanktonai. The Upper Yanktonai live in the northern part of Standing Rock Reservation, on the Spirit Lake Reservation in central North Dakota. Others live in the eastern half of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeastern Montana. In addition, they reside at several Canadian reserves, including Birdtail, Oak Lake, and Whitecap (formerly Moose Woods).

Modern geographic divisions

The Dakota maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations and communities in North America: in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Montana in the United States; and in Manitoba, southern Saskatchewan in Canada.

The earliest known European record of the Dakota identified them in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin. After the introduction of the horse in the early 18th century, the Sioux dominated larger areas of land—from present day Central Canada to the Platte River, from Minnesota to the Yellowstone River, including the Powder River country.[10]

Modern reservations, reserves, and communities of the Sioux

| Reserve/Reservation[11] | Community | Bands residing | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fort Peck Indian Reservation | Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes | Hunkpapa, Upper Yanktonai (Pabaksa), Sisseton, Wahpeton, and the Hudesabina (Red Bottom), Wadopabina (Canoe Paddler), Wadopahnatonwan (Canoe Paddlerrs Who Live on the Prairie), Sahiyaiyeskabi (Plains Cree-Speakers), Inyantonwanbina (Stone People) and Fat Horse Band of the Assiniboine | Montana, United States |

| Spirit Lake Reservation

(Formerly Devil's Lake Reservation) |

Spirit Lake Tribe

(Mni Wakan Oyate) |

Wahpeton, Sisseton, Upper Yanktonai | North Dakota, USA |

| Standing Rock Indian Reservation | Standing Rock Sioux Tribe | Upper Yanktonai, Hunkpapa | North Dakota, South Dakota, USA |

| Lake Traverse Indian Reservation | Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate | Sisseton, Wahpeton | South Dakota, USA |

| Flandreau Indian Reservation | Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Wahpeton | South Dakota, USA |

| Crow Creek Indian Reservation | Crow Creek Sioux Tribe | Lower Yanktonai | South Dakota, USA |

| Yankton Sioux Indian Reservation | Yankton Sioux Tribe | Yankton | South Dakota, USA |

| Upper Sioux Indian Reservation | Upper Sioux Community

(Pejuhutazizi Oyate) |

Mdewakanton, Sisseton, Wahpeton | Minnesota, USA |

| Lower Sioux Indian Reservation | Lower Sioux Indian Community | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Minnesota, USA |

| Shakopee-Mdewakanton Indian Reservation

(Formerly Prior Lake Indian Reservation) |

Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Minnesota, USA |

| Prairie Island Indian Community | Prairie Island Indian Community | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Minnesota, USA |

| Santee Indian Reservation | Santee Sioux Nation | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute | Nebraska, USA |

| Sioux Valley Dakota Nation Reserve, Fishing Station 62A Reserve* | Sioux Valley First Nation | Sisseton, Mdewakanton, Wahpeton, Wahpekute | Manitoba, Canada |

| Dakota Plains Indian Reserve 6A | Dakota Plains Wahpeton First Nation | Wahpeton, Sisseton | Manitoba, Canada |

| Dakota Tipi 1 Reserve | Dakota Tipi First Nation | Wahpeton | Manitoba, Canada |

| Birdtail Creek 57 Reserve, Birdtail Hay Lands 57A Reserve, Fishing Station 62A Reserve* | Birdtail Sioux First Nation | Mdewakanton, Wahpekute, Yanktonai | Manitoba, Canada |

| Canupawakpa Dakota First Nation, Oak Lake 59A Reserve, Fishing Station 62A Reserve* | Canupawakpa Dakota First Nation | Wahpekute, Wahpeton, Yanktonai | Manitoba, Canada |

| Standing Buffalo 78 Reserve | Standing Buffalo Dakota First Nation | Sisseton, Wahpeton | Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Whitecap 94 Reserve | Whitecap Dakota First Nation | Wahpeton, Sisseton | Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Wahpaton 94A, Wahpaton 94B | Wahpeton Dakota Nation | Wahpeton | Saskatchewan, Canada |

| Wood Mountain 160 Reserve, Treaty Four Reserve Grounds Indian Reserve No. 77* | Wood Mountain | Hunkpapa | Saskatchewan, Canada |

(* Reserves shared with other First Nations)

Language

The Dakota language is a Mississippi Valley Siouan language, belonging to the greater Siouan-Catawban language family. It is closely related to and mutually intelligible with the Lakota language, and both are also more distantly related to the Stoney and Assiniboine languages. Dakota is written in the Latin script and has a dictionary and grammar.[1]

- Eastern Dakota (also known as Santee-Sisseton or Dakhóta)

- Santee (Isáŋyáthi: Bdewákhathuŋwaŋ, Waȟpékhute)

- Sisseton (Sisíthuŋwaŋ, Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ)

- Western Dakota (or Yankton-Yanktonai or Dakȟóta)

- Yankton (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋ)

- Yanktonai (Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna)

- Upper Yanktonai (Wičhíyena)

Notable Dakota people

Historical

- Inkpaduta (Scarlet Point/Red End), Wahpekute Dakota war chief

- Ištáȟba (Sleepy Eye), Sisseton Dakota chief

- Maḣpiya Wic̣aṡṭa (Cloud Man), Mdewakanton Dakota chief

- Ohíyes'a (Charles Eastman), Dakota author, physician and reformer

- Tamaha (One Eye/Standing Moose), Mdewekanton Dakota chief

- Thaóyate Dúta (Little Crow/His Red Nation), Mdewakanton Dakota chief and warrior

- Wanata, War Eagle, Húŋkpathina

- Waŋbdí Tháŋka (Big Eagle), Mdewakanton Dakota chief

- Zitkala-Ša (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, 1876–1938), Yankton author, educator, musician and political activist

Contemporary

- Ella Cara Deloria (1889 – 1971), author, ethnographer, linguist

- Vine Deloria Jr. (1933–2005), Standing Rock author, activist, historian and theologian

- Floyd Red Crow Westerman/Kanghi Duta (1936–2007), Sisseton Wahpeton actor

- John Trudell (1946–2015), Santee activist, American Indian Movement leader

Contemporary Sioux people are also listed under the tribes to which they belong:

By individual tribe

- Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation

- Crow Creek Sioux Tribe of the Crow Creek Reservation

- Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe

- Lower Brule Sioux Tribe of the Lower Brule Reservation

- Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community

- Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate

- Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of North and South Dakota

- Yankton Sioux Tribe of South Dakota

See also

Footnotes

- "Dakota." Ethnologue. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- For a report on the long-established blunder of misnaming the Yankton and the Yanktonai as "Nakota", see the article Nakota

- Barry M. Pritzker, A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000; pg. 316

- for a report on the long-established blunder of misnaming as "Nakota", the Yankton and the Yanktonai, see the article Nakota

- Parks, Douglas R.; & Rankin, Robert L., "The Siouan languages"; in DeMallie, R.J. (ed) (2001). Handbook of North American Indians: Plains (Vol. 13, Part 1, pp. 94–114) [W. C. Sturtevant (Gen. Ed.)]. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution: pp. 97 ff; ISBN 0-16-050400-7.

- Ullrich, Jan (2008). New Lakota Dictionary (Incorporating the Dakota Dialects of Yankton-Yanktonai and Santee-Sisseton). Lakota Language Consortium. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-9761082-9-1.

- not to be confused with the Oglala thiyóšpaye bearing the same name, "Húŋkpathila"

- Riggs, Stephen R. (1893). Dakota Grammar, Texts, and Ethnography. Washington Government Printing Office, Ross & Haines, Inc. ISBN 0-87018-052-5.

- OneRoad, Amos E.; Alanson Skinner (2003). Being Dakota: Tales and Traditions of the Sisseton and Wahpeton. Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-453-X.

- Mails, Thomas E. (1973). Dog Soldiers, Bear Men, and Buffalo Women: A Study of the Societies and Cults of the Plains Indians. Prentice-Hall, Inc. ISBN 0-13-217216-X.

- Johnson, Michael (2000). The Tribes of the Sioux Nation. Osprey Publishing Oxford. ISBN 1-85532-878-X.

Further reading

- Catherine J. Denial, Making Marriage: Husbands, Wives, and the American State in Dakota and Ojibwe Country. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2013.

- Cynthia Leanne Landrum, The Dakota Sioux Experience at Flandreau and Pipestone Indian Schools. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dakota (Sioux). |

- About Dakota Wicohan