Yahya bey Dukagjini

Yahya bey Dukagjini (1498–1582; known in Turkish as Dukaginzâde Yahyâ bey or Taşlicali Yahyâ bey, and in Albanian as Jahja bej Dukagjini) was an Ottoman poet and military figure. He is one of the best-known diwan poets of the 16th century.[1] He wrote in Ottoman Turkish.

Dukaginzâde Yahyâ | |

|---|---|

Extract from Gencine-i Raz, a diwan literature work of Yahya bey Dukagjini, National Manuscript Library, Istanbul | |

| Born | 1498 Taşlıca, Sanjak of Herzegovina |

| Died | 1582 (mostly accepted) |

| Occupation | Poet, military |

| Language | Ottoman Turkish |

| Nationality | Ottoman |

| Education | Acemi oglan |

| Literary movement | Diwan poetry |

The Ottomans recruited Dukagjini through the devşirme system in his early youth. In addition to being a poet, he was an important Ottoman military figure during the expansion and apogee period of the empire, serving as a bölükbaşı (senior captain) and participating in the 1514 Battle of Chaldiran, the 1516–17 Ottoman–Mamluk War, the Baghdad expedition of 1535, and the Siege of Szigetvár in 1566. Because of an elegy that he wrote about Şehzade Mustafa, Suleiman the Magnificent's first-born son, he fell out of favor with the perpetrator of the murder, Grand Vizier, Rüstem Pasha, who exiled Dukagjini back to the Balkans, where he spent his last years.

As a poet, Dukagjini is noted for his originality. Despite borrowing some themes from Persian literature, he told stories in his own manner, such as in his poem Yusuf ve Züleyha. His subsequent work, a diwan of poems and of a collection of five mesnevî, parts ways with the influence of Persian tradition.

Life

Early life

Yahya was born in 1498 in Taşlıca (modern day Pljevlja in Montenegro), therefore sometimes he is named Taşlicali (English: from Taslica) although according to the Turkish poet Muallim Naci he did not use the title "Taşlicali".[2] He was related to the other Ottoman poet Dukaginzade Ahmad Bey.[3] The exact year of birth is unknown but is believed to be 1498. An Albanian by birth, according to Elsie descendant of the Catholic Dukagjini tribe which lays in a mountainous region close to the Prokletije, or Dukagjini noble family according to Houtsma, his life took a different path when he was recruited as an Ottoman devşirme.[3] Yahya was enlisted to become a janissary, he was put in the corps of "Acemi oglan" where officers for janissaries and spahis were trained and received the rank of yayabashi (infantry officer) and bölükbaşı (senior captain). The Shihāb al-Dīn, the Katib (secretary) of the janissaries, recognized his skills and accredited him a lot of freedom, which he used to get access to an intellectual coterie composed of Kadri Efendy, Ibn Kemal, Nishandji Tadji-zade Dja'fer Çelebi, Pargalı Ibrahim Pasha, and İskender Çelebi.[3]

Yahya stayed aware of his origin and referenced it in his verses.[4] Nevertheless, for Yahya Bey, the cruel devşirme was his opportunity for rise to fame, considering that back then birth did not count much, whereas good luck and particularly tact with superiors mattered greatly.[3]

Rise as a soldier and poet

Yahya Bey is known to have taken part during his youth in the Battle of Chaldiran of 23 August 1514 led by Sultan Selim I, also in the Ottoman–Mamluk War of 1516–17, and in Baghdad's expedition of 1535 under Sultan Suleiman. He earned the respect of powerful key people (between others the Sultan himself) because of his poetry.[5] Yahya spent most of his early years in Ottoman campaigns, which inspired him.[4] According to E. J. W. Gibb, he was inspired to write the "Yusuf and Züleyha" while in Palestine, on the road to Mecca. Egypt was also an inspiration for him, especially Cairo, which he called "the city of Joseph".[6]

Yahya was a bitter enemy of Khayali Mehmed Bey,[7] another contemporary poet whom he had first met in 1536. He satirically attacked Khayali Mehmed Bey in his verses. Yahya wrote a qasida (a kind of panegyric) against him and presented it during the Persian campaign to the Sultan and Grand Vizier Rüstem Paşa, who was declared as "enemy of the poets". Rustem Pasha was so delighted with the level of contempt towards Khayali, that Yahya was made administrator of several foundations in Bursa and Istanbul.[3][5]

Exile and last years

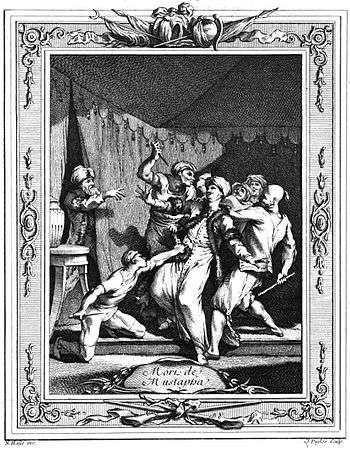

In 1553, near Ereğli in Konya, Suleiman the Magnificent, whilst on a military campaign to Iran, and upon false information given to him from Grand Vizier Rüstem Pasha, had his first born, Prince Şehzade (Prince) Mustafa executed. Yahya Bey wrote an elegy named Şehzade Mersiyesi (Prince's Dirge) upon the murder, which was well received by the public. But the mastermind behind the murder, Rüstem Pasha, was not happy at all about the poem. He had Yahya summoned and asked how he "dared to bewail one whom the Sultan had condemned". Yahya responded "we indeed condemned him with the Sultan, but we bewailed him with the people".[8]

[a] ...

Yalancınun kuru bühtânı bugz-ı pinhânı / Akıtdı yaşumuzı yakdı nâr-ı hicrânı

(The slander and the secret grudge of the liars shed tears from our eyes; ignited the fire of separation}

Cinâyet itmedi cânî gibi anun cânı / Boguldı seyl-i belâya tagıldı erkânı

(He never murdered anybody, but his life was drowned in the flood of calamity, his comrades were disbanded}

N'olaydı görmeye idi bu mâcerâyı gözüm / Yazuklar ana revâ görmedi bu râyı gözüm

(I wish I had never seen this event. What a shame: my eyes didn't approve this treatment to him)

...

The Vizier wanted and did everything he could to get Yahya executed.[3] The Sultan prohibited his execution but approved only to deprive him from his offices, which Rüstem Pasha did in the most offensive manner.[8] As a member of the askeri class, apparently he could not be left to starve.[9] In order to escape persecution, Yahya went to exile back in the Balkans, without forgetting to write a satirical lament on Rustem Pasha after his death. There are divergences on the location where he was sent. According to some sources, he took over a fief near Zvornik in today's Bosnia and lived pretty well afterwards receiving a 27,000[3] or 30,000[9] akçe annual income.[4] Others point to Tamışvar, center of the Province of Temeşvar,[5] where he for sure fought at a certain point.[3] Though not young anymore, he took part together with his men at the siege of Szigetvar in 1565. There he wrote a qasida and presented it to Sultan Suleiman. After that, due to his age, he turned to Islamic Mysticism.

While in exile in Bosnia, Yahya met in 1574-75 with Mustafa Âlî, a local and well known Ottoman historian and bureaucrat. The life-story of Yahya made an impression on Ali, who would later use it as a baseline when he referred to himself as "a poet too talented to be supported by jealous politicians and subsequently condemned to exile in the border provinces".[9] Yahya sent his son, Adem Çelebi, to Ali with a draft of the most recent revision of his diwan for Ali to proofread, especially the Arabic construction parts, although apparently there was no need for that.[9]

There is no wide consensus for Yahya bey's year of death. Most of the sources pointing to 1582,[4][10] while others say he may have died in 1575,[11] 1573 (982 in IC), 1578-79 (986 in IC), or 1582 (990).[3] Place of death also varies. Most sources indicate Loznica, Sanjak of Zvornik,[4] some Timișoara in Romania,[5] There are also claims that he was buried in Istanbul, while Bursalı Mehmet Tahir Bey and Muhamed Hadžijahić place also Loznica as place of death.[2]

Poetry

Yahya's poetry is described by E.J.W.Gibb to be as interesting as his life was. Gibb praised Dukagjini as the one who won a position of real eminence, out of all non-Turks, Asiatics, and well as Europeans, who have essayed to write Turkish poetry. According to Gibb, there is nothing in Dukagjini's language to spot him as a non-Constantinopolitan by birth and education. Gibb added that there is sustained simplicity, vigor, and originality in Dukagjini's writings.[8] According to Gibb, the originality shows for instance in his poem Yusuf ve Züleyha. The subject of the poem is borrowed from Persian literature, which was so popular during that time, that it was considered a universal theme, nevertheless, he rejects being a translator or paraphraser, but tells the story on a manner of his own.[8]

As he declares himself in the epilogue of Yusuf ve Züleyha:[b]

This fair book, this pearl of wisdom,

Is (of) my own imagining, for the most part;

Translation would not be fitting this story;

I would not take a dead men's sweetmeat into my mouth.

And also in Kitab-ı Usul's epilogue:

I have not translated the words of another,

I have not mixed with it [my poem] the words of strangers.

My tongue has not been the dragoman of the Persians,

I would not eat the food of dead Persians.

Dukagjini's core work consists of a large diwan of poems and of a collection of five mesnevî poems of rhymed couplets. As mentioned above, they lack the influence of Persian traditions.[5] They were put together in a Khamsa ("five poems"). The khamsa forms the most important section of Yahya's work. The most popular of the poems is Shâh u gedâ (The King and the Beggar), his favorite[8] and which he claimed to had finished in just one week, and Yusuf ve Züleyha (Yusuf and Züleyha), a romance on the pure love of two young people.[4][8]

Unlike the first two poems of the khamse, which are mostly lyrical, the last three consist of aphorisms on morality and rules of life. Kitab-ı Usul is divided into 10 "stations" (maqām-s),: each one of them attempts to inculcate moral qualities to the reader and is illustrated by anecdotes, to demonstrate the advantages of following certain right moral paths. The anecdotes are full of descriptions, historic and fictitious, and are derived from all kind of sources. The following couplets are used as a refrain at the end of introductory cantos in most of the "stations", and elsewhere throughout the work:

What need for dispute, and what reason for strife?

By this Book of Precepts ordain thou thy life.

His Gül-i Şadberk (Rose of a Thousand Petals) is a poem which describes Prophet Muhammed's miracles,[10] and was written probably at an old age and has a pure religious tone. Gülşen-i Envar is divided into 40 short sections called "discourses".[8]

The first two poems were published in diwan collections in Istanbul in 1867-1868.[12]

Like many other poets, Yahya's work was inspired by the work of Sufi poet Mevlevî (also known as Rumi, Mevlânâ, or Jalāl ad-Dīn, founder of Mevlevi Order). Mevlevi is referenced in a few places inside Yahya's diwan and khamsa as well, where he is mentioned as "Mevlana", "Molla Hünkar", or "Molla-i Rum". Mevlana is a leading character in three of the khamsa's poems: Gencine-i Raz, Kitab-i Usul, and Gulşen-i Envar. The prominent work of Mevlana, Masnavi, contains a story about Prophet Suleiman, and a mosquito (Süleyman Peygamber'le Sivrisinek), which Yahya retold, without changing it.[2]

Yahya also wrote "Şehrengiz" (City Book), where he describes the cities of Edirne and Istanbul.

Works

The following is a list of Yahya bey Dukajini's works:[3]

- Diwan, printed in Istanbul in 1977 (selections from his Collected Poems were published by Mehmet Çavuşoğlu in 1983).

- Khamsa (Five Poems):

- Şah ü Geda - The King and the Beggar

- Yusuf ve Züleyha - Yusuf and Züleyha

- Gencine-i Raz - Treasure of Secret

- Gülşen-i Envar - Rose Garden of the Lights

- Kitab-ı Usul - Book of Procedures

- Şehrengiz-i İstanbul (City Book of İstanbul), published by Mehmet Çavuşoğlu in Türk Dili ve Edebiyatı Dergisi, 1969

- Şehrengiz-i Edirne (City Book of Edirne)

Two additional poems are usually attributed to Dukagjini:[3]

- Nāz ü-Niyāz (Coyness and Yearning)

- Sulaimān-nāme (Book of Sulaiman: this poem is of around 2,000 verses, but left unfinished)

Legacy

A brave soldier, Dukagjini is remembered as representative of a type which admirably combined the sword with the pen. His independence intertwined with frankness and courage was his most notable trait.[3] Yahya Bey is considered today as one of the greatest Ottoman diwan poets of the time.[1]

In popular culture

Yahya bey Dukagjini is depicted in the Turkish TV series Muhteşem Yüzyıl (The Magnificent Century), performed by Serkan Altunorak.

Notes and references

Notes

^ a: Prince Mustafa Elegy - verses 4-6.

^ b: English translation original by Elias John Wilkinson Gibb.

References

- İ. Güven Kaya (2006), Divan edebiyatı ve toplum (in Turkish), Donkişot, p. 123, ISBN 9789756511527, OCLC 171205539,

Divan edebiyatının büyük şairlerinden biri olan Dukaginzâde (Taşlıcalı) Yahya ...

[One of the greatest poets of the divan literature Dukaginzâde (Taşlıcalı) Yahya ..] - İdris Güven Kaya (2009), Dukagin-zade Taşlıcalı Yahya Bey'in Eserleridne Mevlana Celaleddin [Dukagin-zade Taşlıcalı Yahya Bey work on Mevlana Celaleddin] (PDF), Turkish Studies, 4, Erzincan

- M Th Houtsma (1987), First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936, E.J. Brill, p. 1149, ISBN 9789004082656, OCLC 15549162

- Robert Elsie, Yahya bey DUKAGJINI, Albanian Literature in Translation, archived from the original on 2015-11-17CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Culture and Tourism - TAŞLICALI YAHYA

- H. T. Norris (1993), Islam in the Balkans: Religion and Society Between Europe and the Arab World, University of South Carolina Press, p. 79, ISBN 9780872499775, OCLC 28067651

- Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Bernard Lewis; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1998), The Encyclopaedia of Islam, 10, Brill, p. 352, OCLC 490480645

- Elias John Wilkinson Gibb (1904), Edward Browne (ed.), A History of Ottoman Poetry, 3, London: Luzac & Co, pp. 119–125, OCLC 2110073

- Cornell H. Fleischer (1986), Bureaucrat and intellectual in the Ottoman Empire : the historian Mustafa Âli (1541-1600), Princeton University Press, pp. 63–64, ISBN 9780691054643, OCLC 13011359

- Emine Fetvacı (2013), Picturing History at the Ottoman Court, Indiana University Press, p. 51, ISBN 9780253006783, OCLC 827722621

- Marcel Cornis-Pope; John Neubauer (2006), History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures, Comparative history of literatures in European languages, Book 20, 2, J. Benjamins Pub, p. 498, ISBN 9789027293404

- Muhamed Hadžijahić, Jedan Nepoznati Tuzlanski Hagiološki Katalog [One unknown Tuzla Hagiološki Catalog] (PDF) (in Bosnian), p. 217