Xenophyophorea

Xenophyophorea is a clade of foraminiferans. Members of this class are multinucleate unicellular organisms found on the ocean floor throughout the world's oceans, at depths of 500 to 10,600 metres (1,600 to 34,800 ft).[3][4] They are a kind of foraminiferan that extracts minerals from their surroundings and uses them to form an exoskeleton known as a test.

| Xenophyophorea | |

|---|---|

| |

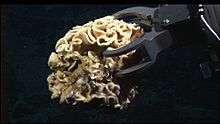

| Image of a deep sea xenophyophore | |

| |

| Xenophyophore at the Galapagos Rift | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Phylum: | Foraminifera |

| Class: | Monothalamea |

| Clade: | Xenophyophorea Schulze, 1904 |

| Orders and subtaxa incertae sedis[1] | |

| |

They were first described by Henry Bowman Brady in 1883. They are abundant on abyssal plains, and in some regions are the dominant species. Fourteen genera and approximately 60 species have been described, varying widely in size.[5] The largest, Syringammina fragilissima, is among the largest known coenocytes, reaching up to 20 centimetres (8 in) in diameter.[6]

Description

Xenophyophores are an important part of the deep sea-floor, as they have been found in all four major ocean basins.[4][7][8][9] However, so far little is known about their biology and ecological role in deep-sea ecosystems.

They seem to be unicellular, but have many nuclei. They form delicate and elaborate agglutinated tests—shells often made of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and other foreign mineral particles glued together with organic cements[10]—that range from a few millimetres to 20 centimetres across. Species of this group are morphologically variable, but the general structural pattern includes a test enclosing a branching system of organic tubules together with masses of waste material (stercomata).[4] The softness and structure of tests varies from soft and lumpy shapes to fans and complex structures.

Xenophyophores are often found in areas of enhanced organic carbon flux, such as beneath productive surface waters, in sub-marine canyons, in settings with sloped topography (e.g. seamounts, abyssal hills) and on continental slopes.[4][6][11][12] They select certain minerals and elements from their environment that are included in its tests and cytoplasm, or concentrated in excretions. The selected minerals vary with species, but often include barite, lead and uranium.[13]

Naming and classification

The name Xenophyophora means "bearer of foreign bodies", from the Greek. This refers to the sediments, called xenophyae, which are cemented together to construct their tests. In 1883, Henry Bowman Brady classified them as primitive Foraminifera.[14] Later they were placed within the sponges.[15] In the beginning of the 20th century they were considered an independent class of Rhizopoda,[16] and later as a new eukaryotic phylum of Protista.[17] As of 2015, recent phylogenetic studies suggest that monothalameans are a specialized group of monothalamous (single-chambered) Foraminifera.[18][19][20]

A 2013 molecular study using small subunit rDNA found Syringammina and Shinkaiya to form a monophyletic clade closely related to Rhizammina algaeformis.[21] Further molecular evidence has confirmed the monophyly of xenophyophores. This study also suggested that many individual genera are polyphyletic, with similar body shapes convergently evolving multiple times.[22]

Feeding

As benthic detritivores, Xenophyophores root through the muddy sediments on the sea floor. They excrete a slimy substance while feeding; in locations with a dense population of Xenophyophores, such as at the bottoms of oceanic trenches, this slime may cover large areas. These giant protozoans seem to feed in a manner similar to amoebas, enveloping food items with a foot-like structure called a pseudopodium. Most are epifaunal (living atop the seabed), but one species (Occultammina profunda), is known to be infaunal; it buries itself up to 6 centimetres (2.4 in) deep into the sediment.

Fossil record

As of 2017, no positively-identified xenophyophore fossils had been identified.[23]

It has been suggested that the mysterious vendozoans of the Ediacaran period represent fossil xenophyophores.[24] However, the discovery of C27 sterols associated with the fossils of Dickinsonia cast doubt on this identification, as these sterols are today associated only with animals. These researchers suggest that Dickinsonia and relatives are instead stem-bilaterians.[25]

Some researchers have suggested that the enigmatic graphoglyptids, known from the early Cambrian through recent times, could represent the remains of xenophyophores,[26] [27] and noted the similarity of the extant xenophyophore Occultammina to the fossil[28]. Supporting this notion is the similar abyssal habitat of living xenophyophores to the inferred habitat of fossil graphoglyptids; however, the large size (up to 0.5m) and regularity of many graphoglyptids as well as the apparent absence of xenophyae in their fossils casts doubt on the possibility.[28] Modern examples of Paleodictyon have been discovered; however, they have not been able to clear up the issue and the trace may alternately represent a burrow or a glass sponge.[29]

Certain Carboniferous fossils have been suggested to represent the remains of xenophyophores due to the concentration of barium within the fossils as well as supposed morphological similarity; however, the barium content was later determined to be due to diagenetic alteration of the material and the morphology of the specimen instead supported an algal affinity.[30]

Ecology

Local population densities may be as high as 2,000 individuals per 100 square metres (1,100 sq ft), making them dominant organisms in some areas. Xenophyophores may be an important part of the benthic ecosystem due to their bioturbation of sediment, providing a habitat for other organisms such as isopods. Research has shown that areas dominated by xenophyophores have 3–4 times the number of benthic crustaceans, echinoderms, and molluscs than equivalent areas that lack xenophyophores. The xenophyophores themselves also play commensal host to a number of organisms—such as isopods (e.g., genus Hebefustis), sipunculan and polychaete worms, nematodes, and harpacticoid copepods—some of which may take up semi-permanent residence within a xenophyophore's test. Brittle stars (Ophiuroidea) also appear to have a relationship with xenophyophores, as they are consistently found directly underneath or on top of the protozoans.

Xenophyophores are difficult to study due to their extreme fragility. Specimens are invariably damaged during sampling, rendering them useless for captive study or cell culture. For this reason, very little is known of their life history. As they occur in all the world's oceans and in great numbers, xenophyophores could be indispensable agents in the process of sediment deposition and in maintaining biological diversity in benthic ecosystems.

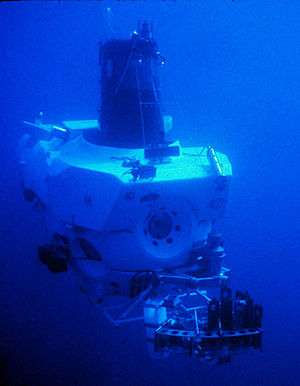

Scientists in the submersible DSV Alvin at a depth of 3,088 metres at the Alaskan continental margin in the Gulf of Alaska collected a spatangoid urchin, Cystochinus loveni, about 5 cm diameter, which was wearing a cloak consisting of over 1,000 protists and other creatures, including 245 living xenophyophores, mainly Psammina species, each 3–6 mm. The fragility of the xenophyophores suggests that the urchin either very carefully collected them, or that they settled and grew there. Among several possible explanations for the urchin's behaviour, perhaps the most likely are chemical camouflage and weighing itself down to avoid being moved in currents.[31]

See also

Further reading

- Gubbay, S., Baker, M., Bettn, B., Konnecker, G. (2002). "The offshore directory: Review of a selection of habitats, communities and species of the north-east Atlantic", pp. 74–77.

- NOAA Ocean Explorer. "Windows to the deep exploration: Giants of the protozoa", p. 2.

External links

References

- Hayward, B.W.; Le Coze, F.; Gross, O. (2019). World Foraminifera Database. Monothalamea. Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=744106 on 2019-01-07

- Tendal, O.S. (1972) A MONOGRAPH OF THE XENOPHYOPHORIA (Rhizopodea, Protozoa)

- MSNBC Staff (22 October 2011). "Giant amoebas discovered in deepest ocean trench". NBC News. Retrieved 2011-10-24.

- Tendal, O. S. (1972). A Monograph of the Xenophyophoria (Rhizopodea, Protozoa) (Doctoral dissertation). Danish Science Press.

- Gooday, A. J.; Tendal, O. S. Class Xenophyophorea Schulze 1904. In: Lee JJ, Leedale GF, Bradbury P, eds. The illustrated guide to the protozoa, 2nd edn. Lawrence, KS: Allen Press. pp. 1086–1097.

- Gooday, A.J; Aranda da Silva, A.; Pawlowski, J. (2011). "Xenophyophores (Rhizaria, Foraminifera) from the Nazare Canyon (Portuguese margin, NE Atlantic)". Deep-Sea Research Part II. 58 (23–24): 2401–2419. Bibcode:2011DSRII..58.2401G. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2011.04.005.

- Levin, L. A.; Gooday, A. J. (1992). Rowe, G. T.; Pariente, V. (eds.). Possible roles for Xenophyophores in dee-sea carbon cycling. In: Deep-Sea Food Chains and the Global Carbon Cycle. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic. pp. 93–104.

- Levin, L. A (1991). "Interactions between metazoans and large, agglutinating protozoans: implications for the community structure of deep-sea benthos". American Zoologist. 31 (6): 886–900. doi:10.1093/icb/31.6.886.

- Tendal, O. S. (1996). "Synoptic checklist and bibliography of the Xenophyophorea (Protista), with a zoogeopgraphical survey of the group" (PDF). Galathea Report. 17: 79–101.

- London, Postgraduate Unit of Micropalaeontology, University College (2002). "Foraminifera". www.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- Tendal, O. S.; Gooday, A. J. (1981). "Xenophyophoria (Rhizopoda, Protozoa) in bottom photographs from the bathyal and abyssal NE Atlantic" (PDF). Oceanologica Acta. 4: 415–422.

- Levin, L. A.; DeMaster, D. J.; McCann, L. D.; Thomas, C. L. (1986). "Effect of giant protozoans (class: Xenophyophorea) on deep-seamount benthos". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 29: 99–104. Bibcode:1986MEPS...29...99L. doi:10.3354/meps029099.

- Rothe, N.; Gooday, A. J.; Pearce, R. B. (2011-12-01). "Intracellular mineral grains in the xenophyophore Nazareammina tenera (Rhizaria, Foraminifera) from the Nazaré Canyon (Portuguese margin, NE Atlantic)". Deep-Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers. 58 (12): 1189–1195. Bibcode:2011DSRI...58.1189R. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2011.09.003.

- Brady, H.B. (1884). "Report on the Foraminifera. Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H. M. S. Challenger". 9: 1–814. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Haeckel, E. (1889). "Report on the scientific results of the voyage of H. M. S. Challenger during the years 1873–76". Zoology. 32: 1–92.

- Schulze, F. E. (1907). "Die Xenophyophoren, eine besondere Gruppe der Rhizopoden". Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Deutschen Tiefsee-Expedition Auf dem Dampfer 'Validivia' 1898–1899. 11: 1–55.

- Lee, J. J.; Leedale, G. F.; Bradbury, P. (2000). The illustrated guide to the protozoa (2nd ed.). Society of protozoologists. Lawrence, KS: Allen Press.

- Pawlowski, J.; Holzmann, M.; Fahrni, J.; Richardson, S.L. (2003). "Small subunit ribosomal DNA suggests that the xenophyophorean Syringammina corbicula isa Foraminiferan". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 50 (6): 483–487. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2003.tb00275.x. PMID 14733441.

- Lecroq, Béatrice; Gooday, Andrew John; Tsuchiya, Masashi; Pawlowski, Jan (2009-07-01). "A new genus of xenophyophores (Foraminifera) from Japan Trench: morphological description, molecular phylogeny and elemental analysis". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 156 (3): 455–464. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2008.00493.x. ISSN 1096-3642.

- Gooday, A. J.; Aranda da Silva, A.; Pawlowski, J. (2011-12-01). "Xenophyophores (Rhizaria, Foraminifera) from the Nazaré Canyon (Portuguese margin, NE Atlantic)". Deep-Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. The Geology, Geochemistry, and Biology of Submarine Canyons West of Portugal. 58 (23–24): 2401–2419. Bibcode:2011DSRII..58.2401G. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2011.04.005.

- Pawlowski, Jan; Holzmann, Maria; Tyszka, Jarosław (2013-04-01). "New supraordinal classification of Foraminifera: Molecules meet morphology". Marine Micropaleontology. 100: 1–10. Bibcode:2013MarMP.100....1P. doi:10.1016/j.marmicro.2013.04.002. ISSN 0377-8398.

- Gooday, Andrew J; Holzmann, Maria; Caulle, Clémence; Goineau, Aurélie; Kamenskaya, Olga; Weber, Alexandra A. -T.; Pawlowski, Jan (2017-03-01). "Giant protists (xenophyophores, Foraminifera) are exceptionally diverse in parts of the abyssal eastern Pacific licensed for polymetallic nodule exploration". Biological Conservation. 207: 106–116. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.01.006. ISSN 0006-3207.

- Gooday, Andrew J; Holzmann, Maria; Caulle, Clémence; Goineau, Aurélie; Kamenskaya, Olga; Weber, Alexandra A. -T.; Pawlowski, Jan (2017-03-01). "Giant protists (xenophyophores, Foraminifera) are exceptionally diverse in parts of the abyssal eastern Pacific licensed for polymetallic nodule exploration". Biological Conservation. 207: 106–116. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.01.006. ISSN 0006-3207.

- Seilacher, A. (2007-01-01). "The nature of vendobionts". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 286 (1): 387–397. Bibcode:2007GSLSP.286..387S. doi:10.1144/SP286.28. ISSN 0305-8719.

- Bobrovskiy, Ilya; Hope, Janet M.; Ivantsov, Andrey; Nettersheim, Benjamin J.; Hallmann, Christian; Brocks, Jochen J. (2018-09-21). "Ancient steroids establish the Ediacaran fossil Dickinsonia as one of the earliest animals". Science. 361 (6408): 1246–1249. Bibcode:2018Sci...361.1246B. doi:10.1126/science.aat7228. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 30237355.

- Jensen, Soren. "Jensen, S. and Palacios, T. 2006. A peri-Gondwanan cradle for the trace fossil Paleodictyon. In: 22 Jornadas de Paleontologia, Comunicaciones, 132-134". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Swinbanks, D. D. (1982-10-01). "Piaeodicton: The Traces of Infaunal Xenophyophores?". Science. 218 (4567): 47–49. Bibcode:1982Sci...218...47S. doi:10.1126/science.218.4567.47. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17776707.

- Levin, Lisa A. (1994). "Paleoecology and Ecology of Xenophyophores". PALAIOS. 9 (1): 32–41. Bibcode:1994Palai...9...32L. doi:10.2307/3515076. ISSN 0883-1351. JSTOR 3515076.

- Rona, Peter A.; Seilacher, Adolf; de Vargas, Colomban; Gooday, Andrew J.; Bernhard, Joan M.; Bowser, Sam; Vetriani, Costantino; Wirsen, Carl O.; Mullineaux, Lauren; Sherrell, Robert; Frederick Grassle, J. (2009-09-01). "Paleodictyon nodosum: A living fossil on the deep-sea floor". Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. Marine Benthic Ecology and Biodiversity: A Compilation of Recent Advances in Honor of J. Frederick Grassle. 56 (19): 1700–1712. Bibcode:2009DSRII..56.1700R. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2009.05.015. ISSN 0967-0645.

- Torres, Andrew M. (1996). "Fossil algae were very different from xenophyophores". Lethaia. 29 (3): 287–288. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1996.tb01661.x. ISSN 1502-3931.

- Levin, Lisa A.; Gooday, Andrew J.; James, David W. (2001). "Dressing up for the deep: agglutinated protists adorn an irregular urchin". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK. 81 (5): 881. doi:10.1017/S0025315401004738. ISSN 0025-3154.