Three-volume novel

The three-volume novel (sometimes three-decker or triple decker) was a standard form of publishing for British fiction during the nineteenth century. It was a significant stage in the development of the modern novel as a form of popular literature in Western culture.

History

Three volume novels began to be produced by the Edinburgh-based publisher Archibald Constable in the early 19th century. Constable was one of the most significant publishers of the 1820s and made a success of publishing expensive, three-volume editions of the works of Walter Scott, the first being Scott's historical novel Kenilworth, published in 1821.[1] This continued until Constable's company collapsed in 1826 with large debts, bankrupting both him and Scott.[2] As Constable's company collapsed, the publisher Henry Colburn quickly adopted the format. The number of three-volume novels he issued annually rose from six in 1825 to 30 in 1828 and 39 in 1829. Under Colburn's influence, the published novels adopted a standard format of three volumes in octavo, priced at 31 shillings and sixpence. The price and format remained unaltered for nearly 70 years, until 1894.[3]

Three-volume novels quickly disappeared after 1894, when both Mudie's and W. H. Smith stopped purchasing them.[4]

Description

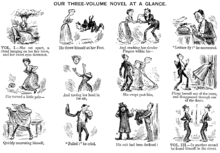

The format of the three-volume novel does not correspond closely to what would now be considered a trilogy of novels. In a time when books were relatively expensive to print and bind, publishing longer works of fiction had a particular relationship to a reading public who borrowed books from commercial circulating libraries. A novel divided into three parts could create a demand (Part I whetting an appetite for Parts II and III). The income from Part I could also be used to pay for the printing costs of the later parts. Furthermore, a commercial librarian had three volumes earning their keep, rather than one. The particular style of mid-Victorian fiction, of a complicated plot reaching resolution by distribution of marriage partners and property in the final pages, was well adapted to the form.

The standardized cost of a three volume novel was equivalent to half the weekly income of a modest, middle-class household.[5] This cost was enough to deter even comparatively well-off members of the public from buying them. Instead, they were borrowed from commercial circulating libraries, the most well known being owned by Charles Edward Mudie.[6] Mudie was able to buy novels for stock at about half the retail price – five shillings per volume.[6] He charged his subscribers one guinea (21 shillings) a year for the right to borrow one volume at a time. A subscriber who wished to borrow three volumes, in order to read the complete novel without having to make two additional trips to the library, had to pay a higher annual fee.[7]

Their high price meant both publisher and author could make a profit on the comparatively limited sales of such expensive books – three volume novels were typically printed in editions of under 1000 copies, which were often pre-sold to subscription libraries before the book was even published.[1] It was very unusual for a three-volume novel to sell more than 1000 copies.[8] The system encouraged publishers and authors to produce as many novels as possible, due to the almost-guaranteed, but limited, profits that would be made on each.[1]

The normal three-volume novel was around 900 pages in total at 150–200,000 words; the average length was 168,000 words in 45 chapters. It was common for novelists to have contracts specifying a set number of pages to be filled. If they ran under, they could be made to produce extra, or break the text up into more chapters — each new chapter heading would fill a page. In 1880, the author Rhoda Broughton was offered £750 by her publisher for her two-volume novel Second Thoughts. However, he offered her £1200 if she could add a third volume.[7]

Other forms of Victorian publication

Outside of the subscription library system's three-volume novels, the public could access literature in the form of partworks - the novel was sold in around 20 monthly parts, costing one shilling each. This was a form used for the first publications of many of the works of Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope and William Thackeray. Many novels by authors such as Wilkie Collins and George Eliot were first published in serial form in weekly and monthly magazines that began to become popular in the middle of the 19th century. Publishers also offered cheap, reprint editions of many works, priced at one to two shillings.[9] Although there was often a lengthy delay before reprint editions were released. Those who wished to access the latest books had no choice but to borrow three volume editions from a subscription library.[6]

The cheapest works of popular fiction were sometimes referred to pejoratively as penny dreadfuls. These were popular with young, working-class men,[10] and often had sensationalist stories featuring criminals, detectives, pirates or the supernatural.

20th-century

Though the era of the three volume novel effectively ended in 1894, works were still on occasion printed in more than one volume in the 20th-century. Two of John Cowper Powys's novels, Wolf Solent (1929) and Owen Glendower (1940) were published in two volume editions by Simon & Schuster in the USA.

The Lord of the Rings is a three-volume novel, rather than a trilogy, as Tolkien originally intended the work to be the first of a two-work set, the other to be The Silmarillion, but this idea was dismissed by his publisher.[11][12] For economic reasons The Lord of the Rings was published in three volumes from 29 July 1954 to 20 October 1955.[11][13] The three volumes were entitled The Fellowship of the Ring, The Two Towers, and The Return of the King.

Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami has written several books in this format, such as The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle and 1Q84. However, many translations of the novel, such as into English, combine the three volumes of these novels into a single book.

References in literature

- Austen, Pride and Prejudice (1813), chapter 11 ("Darcy took up a book; Miss Bingley did the same;...At length, quite exhausted by the attempt to be amused with her own book, which she had only chosen because it was the second volume of his,")

- Dixon, The Story of a Modern Woman (1894) ("No. My idea was too sad—too painful, all the publishers said. It wouldn't have pleased the British public. But I have been given a commission to do a three-volume novel on the old lines—a ball in the first volume; a picnic and a parting in the second; and an elopement, which must, of course, be prevented at the last moment by the opportune death (in a hospital) of the wife, or the husband—I forget which it is to be—in the last.").

- Trollope, The Way We Live Now (1875), Chapter LXXXIX ("The length of her novel had been her first question. It must be in three volumes, and each volume must have three hundred pages.").

- Jerome, Three Men in a Boat (1889), Chapter XII ("The London Journal duke always has his "little place" at Maidenhead; and the heroine of the three-volume novel always dines there when she goes out on the spree with somebody else's husband.").

- Kipling, "The Three-Decker" (1894), Text , Commentary

- Wilde, The Critic as Artist (1890), ("Anybody can write a three-volume novel, it merely requires a complete ignorance of both life and literature").

- Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), Act II ("I believe that Memory is responsible for nearly all the three-volume novels that Mudie sends us." "Do not speak slightingly of the three-volume novel, Cecily.") and Act III ("It contained the manuscript of a three-volume novel of more than usually revolting sentimentality.").

See also

- Victorian literature

- Word count

- Novel sequence

Sources

- A New Introduction to Bibliography, Philip Gaskell. Oxford, 1979. ISBN 0-19-818150-7

- Mudie's Select Library and the Form of Victorian Fiction, George P. Landow. The Victorian Web.

References

- Patrick Brantlinger; William Thesing (15 April 2008). A Companion to the Victorian Novel. John Wiley & Sons. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-470-99720-8.

- John Kucich; Jenny Bourne Taylor (2012). The Oxford History of the Novel in English: Volume 3: The Nineteenth-Century Novel 1820-1880. OUP Oxford. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-956061-5.

- John Kucich; Jenny Bourne Taylor (2012). The Oxford History of the Novel in English: Volume 3: The Nineteenth-Century Novel 1820-1880. OUP Oxford. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-19-956061-5.

- Draznin, Yaffa Claire (2001). Victorian London's Middle-Class Housewife: What She Did All Day (#179). Contributions in Women's Studies. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 151. ISBN 0-313-31399-7.

- Deirdre David (2001). The Cambridge Companion to the Victorian Novel. Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-521-64619-2.

- Landow, George (2001). "Mudie's Select Library and the Form of Victorian Fiction". Victorian Web. Retrieved August 11, 2016.

- Deirdre David. The Cambridge Companion to the Victorian Novel. Cambridge University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-107-49564-7.

- Incorporated Society of Authors (Great Britain) (1891). The cost of production : being specimens of the pages and type in more common use, with estimates of the cost of composition, printing, paper, binding, etc., for the production of a book. [London] : Printed for the Incorporated Society of Authors. p. 17. OCLC 971575827.

- Patrick Brantlinger; William Thesing (15 April 2008). A Companion to the Victorian Novel. John Wiley & Sons. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-470-99720-8.

- James, Louis (1974). Fiction for the Working Man, 1830-50. Harmondsworth: Penguin University Books. ISBN 0-14-060037-X. p.20

- Reynolds, Pat. "The Lord of the Rings: The Tale of a Text". The Tolkien Society. Archived from the original on 18 February 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981), The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, #126., ISBN 0-395-31555-7

- "The Life and Works for JRR Tolkien". BBC. 7 February 2002. Retrieved 4 December 2010.