Women's association football

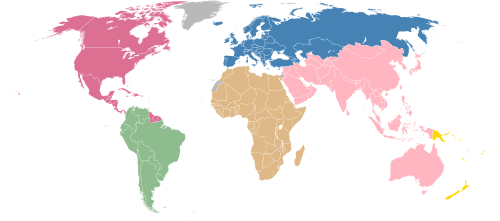

Women's association football, usually known as women's football or women's soccer, is the team sport of association football when played by women's teams only. It is played at the professional level in numerous countries throughout the world and 176 national teams participate internationally.[1][2]

The history of women's football has seen major competitions being launched at both the national and international levels. Women's football has faced many struggles throughout its history. Although its first golden age occurred in the United Kingdom in the early 1920s, with matches attracting large crowds (one match achieved over 50,000 spectators),[3] The Football Association initiated a ban in 1921 in England that disallowed women's football games from taking place on the grounds used by its member clubs. This ban remained in effect until July 1971.[4]

The inaugural FIFA Women's World Cup was held in China in 1991.[5] Since then, the sport has gained in popularity.[6] The 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup Final in Canada was the most watched soccer game in United States history[7] and over 1.12 billion people worldwide watched the 2019 FIFA Women's World Cup in France.[8]

History

Early women's football

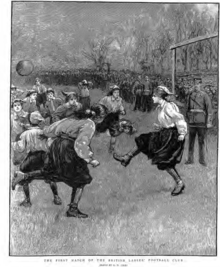

Women may have been playing football for as long as the game has existed. Evidence shows that a similar game (cuju) was played by women during the Han Dynasty (25–220 CE). Two female figures are depicted in Han Dynasty frescoes, playing Tsu Chu.[9] There are, however, a number of opinions about the accuracy of dates, the earliest estimates at 5000 BCE.[10] Reports of an annual match being played in Scotland are reported as early as the 1790s.[11][12] The first match recorded by the Scottish Football Association took place in 1892 in Glasgow. In England, the first recorded game of football between women took place in 1895.[13][14]

The modern game of football (soccer) has documented early involvement of women. In Europe, it is possible that 12th-century French women played football as part of that era's folk games. An annual competition in Mid-Lothian, Scotland during the 1790s is reported, too.[11][12] In 1863, football governing bodies introduced standardized rules to prohibit violence on the pitch, making it more socially acceptable for women to play.[13]

The most well-documented early European team was founded by activist Nettie Honeyball in England in 1894. It was named the British Ladies' Football Club. Honeyball and those like her paved the way for women's football. However the women's game was frowned upon by the British football associations, and continued without their support. It has been suggested that this was motivated by a perceived threat to the 'masculinity' of the game.[15]

.jpg)

Women's football became popular on a large scale at the time of the First World War, when employment in heavy industry spurred the growth of the game, much as it had done for men fifty years earlier. A team from England played a team from Ireland on Boxing Day 1917 in front of a crowd of 20,000 spectators.[16] The most successful team of the era was Dick, Kerr's Ladies of Preston, England. The team played in the first women's international matches in 1920, against a team from Paris, France, in April, and also made up most of the England team against a Scottish Ladies XI in 1920, winning 22–0.[11]

FA Ban (1921–1971)

Despite being more popular than some men's football events (one match saw a 53,000 strong crowd),[17] women's football in England was halted in 1921 when The Football Association outlawed the playing of the game on Association members' pitches, on the grounds stating that "the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged."[18][19] Some speculated that this may have also been due to envy of the large crowds that women's matches attracted.[20] Despite the ban, some women's teams continued to play. The English Ladies Football Association was formed and play moved to rugby grounds.[21]

The ban was maintained by the FA for fifty years until 1971. The same year, UEFA recommended that the national associations in each country should manage the women's game.[22] It was not until 2008 (87 years later), that the FA issued an apology for banning women from the game of football.[23][24] Six years prior in 2002, Lily Parr of Dick Kerr's Ladies FC, was the first woman to be inducted into the National Football Museum Hall of Fame. She was later honoured with a statue in front of the museum.[25]

Competitions

- The Munitionettes' Cup

In August 1917, a tournament was launched for female munition workers' teams in northeast England. Officially titled the Tyne Wear & Tees Alfred Wood Munition Girls Cup, it was popularly known as The Munitionettes' Cup.[26] The first winners of the trophy were Blyth Spartans, who defeated Bolckow Vaughan 5–0 in a replayed final tie at Middlesbrough on 18 May 1918 in front of a crowd of 22,000.[27] The tournament ran for a second year in season 1918–19, the winners being the ladies of Palmer's shipyard in Jarrow, who defeated Christopher Brown's of Hartlepool 1–0 at St James' Park in Newcastle on 22 March 1919.[28]

- The English Ladies' Football Association Challenge Cup

Following the FA ban on women's teams on 5 December 1921, the English Ladies' Football Association was formed.[29][30] A silver cup was donated by the first president of the association, Len Bridgett. A total of 24 teams entered the first competition in the spring of 1922. The winners were Stoke Ladies who beat Doncaster and Bentley Ladies 3–1 on 24 June 1922.[31]

- The Championship of Great Britain and the World

In 1937 and 1938, the Dick, Kerr's Ladies F.C. played Edinburgh City Girls in the "Championship of Great Britain and the World". Dick Kerr won the 1937 and 38 competitions with 5–1 score lines. The 1939 competition however was a more organised affair and the Edinburgh City Girls beat Dick Kerr in Edinburgh 5–2. The City Girls followed this up with a 7–1 demolition of Glasgow Ladies Ladies in Falkirk to take the title.[32]

The 'revival' of the women's game

The English Women's FA was formed in 1969 (as a result of the increased interest generated by the 1966 World Cup),[33] and the FA's ban on matches being played on members' grounds was finally lifted in 1971.[13] In the same year, UEFA recommended that the women's game should be taken under the control of the national associations in each country.[33]

Ladies World Championships, 1970 and 1971

In 1970 an Italian ladies football federation, known as Federazione Femminile Italiana Giuoco Calcio or FFIGC, ran a "World Championships" tournament in Rome supported by the Martini and Rossi strong wine manufacturers, entirely without the involvement of FIFA or any of the common National associations.[34] This event was at least partly played by clubs.[35] But a somewhat more successful World Championships with national teams was hosted by Mexico the following year. The final (won by Denmark) was played at the famous Estadio Azteca, the largest arena in the entire Americas north of the Panama Canal at the time, in front of no less than 112.500 attenders.[36]

On 17 April 1971, in the French town of Hazebrouck, the first official women's international football match was played between France and the Netherlands.[37]

Professionalism

During the 1970s, Italy became the first country to introduce professional women's football players, on a part-time basis. Italy was also the first country to import foreign footballers from other Europeans countries, which raised the profile of the league. The most prominent players during that era included Susanne Augustesen (Denmark), Rose Reilly and Edna Neillis (Scotland), Anne O'Brien (Ireland) and Concepcion Sánchez Freire (Spain).[38]

Asia and Oceania

In 1989, Japan became the first country to have a semi-professional women's football league, the L. League – still in existence today as Division 1 of the Nadeshiko League.[39][40]

In Australia, the W-League was formed in 2008.[41]

In 2015, the Chinese Women's Super League (CWSL) was launched with an affiliated second division, CWFL.[42] Previously, The Chinese Women's Premier Football League was initiated in 1997 and evolved to the Women's Super League in 2004. From 2011 to 2014, the league was named the Women's National Football League.

The Indian Women's League was launched in 2016. The country has held the top-tier tournament, Indian Women's Football Championship, since 1991.[43]

North America

In 1985, the United States national soccer team was formed.[44] Following the success of the 1999 FIFA Women's World Cup, the first professional women's soccer league in the United States, the WUSA, was launched, and lasted three years. The league was spearheaded by members of the World Cup-winning American team and featured players like Mia Hamm, Julie Foudy, Brandi Chastain[45] as well as top-tier international players like Germany's Birgit Prinz and China's Sun Wen.[46] A second attempt towards a sustainable professional league, the Women's Professional Soccer (WPS), was launched in 2009 and folded in late 2011.[47] The following year, the National Women's Soccer League (NWSL) was launched with initial support from the United States, Canadian, and Mexico federations.[48] As of 2020, it is in its eighth year.

In 2017, Liga MX Femenil was launched in Mexico and broke several attendance records. The league is composed of women's teams for the men's counterpart teams in Liga MX.[49]

21st century

At the beginning of the 21st century, women's football, like men's football, is growing in both popularity and participation[50] as well as more professional leagues worldwide.[51] From the inaugural FIFA Women's World Cup tournament held in 1991[52] to the 1,194,221 tickets sold for the 1999 Women's World Cup[53] visibility and support of women's professional football has increased around the globe.[54]

However, as in numerous other sports, women's pay and opportunities are much lower in comparison with professional male football players.[55][56] Major league and international women's football have far less television and media coverage than the men's equivalent.[57] Games can be regarded as being an ordeal to be "endured rather than enjoyed... more out of duty than expectation".[58] The popularity and participation in women's football continues to grow.[59] While several features continue to improve, this is not the case for female coaches. They continue to be underrepresented in several European women's leagues.[60]

International competitions

The growth in women's football has seen major competitions being launched at both the national and international levels.

Women's World Cup

Prior to the 1991 establishment of the FIFA Women's World Cup, several unofficial world tournaments took place in the 1970s and 1980s,[61] including the FIFA's Women's Invitation Tournament 1988, which was hosted in China.[62]

The first Women's World Cup was held in the People's Republic of China, in November 1991, and was won by the United States (USWNT). The third Cup, held in the United States in June and July 1999, drew worldwide television interest and a final in front of a record-setting 90,000+ Pasadena crowd, where the United States won 5–4 on penalty kicks against China.[63][64] The US are the reigning champions, having won in Canada in 2015, and in France, in 2019.

Olympics

Since 1996, a Women's Football Tournament has been staged at the Olympic Games. Unlike in the men's Olympic Football tournament (based on teams of mostly under-23 players), the Olympic women's teams do not have restrictions due to professionalism or age.

England and other British Home Nations are not eligible to compete as separate entities because the International Olympic Committee does not recognise their FIFA status as separate teams in competitions. The participation of UK men's and women's sides at the 2012 Olympic tournament was a bone of contention between the four national associations in the UK from 2005, when the Games were awarded to London, to 2009. England was strongly in favour of unified UK teams, while Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland were opposed, fearing adverse consequences for the independent status of the Home Nations within FIFA. At one stage it was reported that England alone would field teams under the UK banner (officially "Great Britain") for the 2012 Games.[65] However, both the men's and women's Great Britain teams eventually fielded some players from the other home nations. (See Football at the 2012 Summer Olympics – Women's tournament)

UEFA Women's Championship

What is now known worldwide as the UEFA Women's Championship (or Women's Euro) was initially launched in 1982 under the name European Competition For Representative Women's Teams and recognized by UEFA as an official tournament. Previously, European women's tournaments featuring national teams were held in Italy in 1969 [66] and 1979[67], but were not recognized as "official" due to the FA Ban.

The 1984 Finals was won by Sweden. Norway won, in the 1987 Finals. Since then, the UEFA Women's Championship has been dominated by Germany, which has won eight out of the 10 events to date. The only other teams to win are Norway, which won in 1993, and the reigning champions, the Netherlands, which won at home in 2017.

Copa Libertadores Femenina

Copa Libertadores Femenina (Women's Liberators Cup), formally known as CONMEBOL Libertadores Femenina, is the international women's football club competition for teams that play in CONMEBOL nations. The competition started in the 2009 season in response to the increased interest in women's football. It is the only CONMEBOL club competition for women.[68]

Domestic competitions

England

Football Association Women's Challenge Cup (FA Women's Cup)

After the lifting of The FA ban, the now defunct Women's Football Association held its first national knockout cup in 1970–71. It was called the Mitre Trophy which became the FA Women's Cup in 1993. Southampton WFC was the inaugural winner. From 1983 to 1994 Doncaster Belles reached ten out of 11 finals, winning six of them. Chelsea are the current holders and Arsenal are the most successful club with a record 14 wins.[69] Despite tournament sponsorship by major companies, entering the cup actually costs clubs more than they get in prize money. In 2015 it was reported that even if Notts County had won the tournament outright the paltry £8,600 winnings would leave them out of pocket.[70] The winners of the men's FA Cup in the same year received £1.8 million, with teams not even reaching the first round proper getting more than the women's winners.[71]

Youth tournaments

In 2002, FIFA inaugurated a women's youth championship, officially called the FIFA U-19 Women's World Championship. The first event was hosted by Canada. The final was an all-CONCACAF affair, with the USA defeating the host Canadians 1–0 with an extra-time golden goal. The second event was held in Thailand in 2004 and won by Germany. The age limit was raised to 20, starting with the 2006 event held in Russia. Demonstrating the increasing global reach of the women's game, the winners of this event were North Korea. The tournament was renamed the FIFA U-20 Women's World Cup, effective with the 2008 edition won by the US in Chile. The current champions are Japan, who won in France in 2018.[72]

In 2008, FIFA instituted an under-17 world championship. The inaugural event, held in New Zealand, was won by North Korea. The current champions at this level are Spain, who won in Uruguay in 2018.[73]

Intercollegiate

United States

In the United States, the intercollegiate sport began from physical education programs that helped establish organized teams. After sixty years of trying to gain social acceptance women's football was introduced to the college level. In the late 1970s, women's club teams started to appear on college campus, but it wasn't until the 1980s that they started to gain recognition and gained a varsity status. Brown University was the first college to grant full varsity level status to their women's soccer team. The Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) sponsored the first regional women's soccer tournament at college in the US, which was held at Brown University. The first national level tournament was held at Colorado College, which gained official AIAW sponsorship in 1981. The 1990s saw greater participation mainly due to the Title IX of 23 June 1972, which increased school's budgets and their addition of women's scholarships.

"Currently there are over 700 intercollegiate women's soccer teams playing for many types and sizes of colleges and universities. This includes colleges and universities that are members of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA), and the National Junior College Athletic Association (NJCAA)."

Attire

The majority of women footballers around the globe wear a traditional kit made up of a jersey, shorts, cleats and knee-length socks worn over shin guards.

Controversies

In 2004, FIFA President Sepp Blatter suggested that women footballers should "wear tighter shorts and low cut shirts... to create a more female aesthetic" and attract more male fans. His comment was criticized as sexist by numerous people involved with women's football and several media outlets worldwide.[74][75][76]

In September 2008, FC de Rakt women's team (FC de Rakt DA1) in the Netherlands made international headlines by swapping its old kit for a new one featuring short skirts and tight-fitting shirts.[77] This innovation, which had been requested by the team itself, was initially vetoed by the Royal Dutch Football Association on the grounds that according to the rules of the game shorts must be worn by all players, both male and female; but this decision was reversed when it was revealed that the FC de Rakt team were wearing hot pants under their skirts, and were therefore technically in compliance. Denying that the kit change was merely a publicity stunt, club chairman Jan van den Elzen told Reuters:

The girls asked us if they could make a team and asked specifically to play in skirts. We said we'd try but we didn't expect to get permission for that. We've seen reactions from Belgium and Germany already saying this could be something for them. Many girls would like to play in skirts but didn't think it was possible.

21-year-old team captain Rinske Temming said:

We think they are far more elegant than the traditional shorts and furthermore they are more comfortable because the shorts are made for men. It's more about being elegant, not sexy. Female football is not so popular at the moment. In the Netherlands there's an image that it's more for men, but we hope that can change.

In June 2011, Iran forfeited an Olympic qualification match in Jordan, after trying to take to the field in hijabs and full body suits. FIFA awarded a default 3–0 win to Jordan, explaining that the Iranian kits were "an infringement of the Laws of the Game", due to safety concerns.[78] The decision provoked strong criticism from Mahmoud Ahmadinejad[79] while Iranian officials alleged that the actions of the Bahraini match delegate had been politically motivated.[80] In July 2012, FIFA approved the wearing of hijab in future matches.[81]

Also in June 2011, Russian UEFA Women's Champions League contenders WFC Rossiyanka announced a plan to play in bikinis in a bid to boost attendances.[82]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Women's association football. |

TV football

- Geography of women's association football

- International competitions in women's football

- List of women's association football clubs

- Women's sports

- Title IX

- Gracie

- Bend It Like Beckham

- She's the Man

- Alex & Me

- Mustangs FC

References

- "The FIFA Women's World Ranking". FIFA.

- "The FIFA World Ranking". FIFA.

- "Trail-blazers who pioneered women's football". BBC News. 3 June 2005. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- Grainey, Timothy F. (2012). Beyond Bend It Like Beckham: The Global Phenomenon of Women's Soccer. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803240360.

- FIFA.com. "FIFA Women's World Cup 1991 - News - USA triumph as history made in China PR - FIFA.com". www.fifa.com. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "Staggering growth of women's soccer bodes well for World Cup in France". Los Angeles Times. 4 June 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Sandomir, Richard (7 July 2015). "Women's World Cup final was most-watched soccer game in US history". CNBC. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- FIFA.com. "FIFA Women's World Cup 2019 - News - FIFA Women's World Cup 2019 watched by more than 1 billion - FIFA.com". www.fifa.com. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "Genesis of the Global Game". The Global Game. Archived from the original on 21 May 2006. Retrieved 22 May 2006.

- "The Chinese and Tsu Chu". The Football Network. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- "A Brief History of Women's Football". Scottish Football Association. Archived from the original on 8 March 2005. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- "Football history: Winning ways of wedded women" Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- The FA – "Women's Football- A Brief History"

- "How women's football battled for survival". 3 June 2005 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Mårtensson, Stefan (June 2010). "Branding women's football in a field of hegemonic masculinity". Entertainment and Sports Law Journal. 8: 5. doi:10.16997/eslj.44.

- "Home Front – The Forgotten First International Women's Football Match – BBC Radio 4". BBC. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- Leighton, Tony (10 February 2008). "FA apologies for 1921 ban". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "The History of Women's Football in England". The FA. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Witzig, Richard (2006). The Global Art of Soccer. CusiBoy Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 0977668800. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "Trail-blazers who pioneered women's football". 3 June 2005 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Newsham, Gail (2014). In a League of Their Own. The Dick, Kerr Ladies 1917–1965. Paragon Publishing.

- "The female football mania that led to it being banned". 12 December 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "From banned to blooming: the evolution of women's football". RFI. 29 June 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Leighton, Tony (11 February 2008). "Women's football: FA apologies for 1921 ban". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Katz, Brigit. "Lily Parr, a Pioneering English Footballer, Scores Bronze Monument". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Storey, Neil R. (2010). Women in the First World War. Osprey Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-0747807520.

- "Croft Park, Newcastle: Blyth Spartans Ladies FC, World War One At Home". BBC. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- Adie, Kate (2013). Fighting on the Home Front: The Legacy of Women in World War One. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1444759709. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- Taylor, Matthew (2013). The Association Game: A History of British Football. Routledge. p. 135. ISBN 978-1317870081. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- Williams, Jean (2014). A Contemporary History of Women's Sport, Part One: Sporting Women, 1850–1960. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317746652. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- Brennan, Patrick (2007). "The English Ladies' Football Association". Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Murray, Scott (2010). Football For Dummies, UK Edition. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0470664407.

- University of Leicester fact sheet on women's football Archived 18 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Williams, Jean (2014). "2: 'Soccer matters very much, every day'". In Agergaard, Sine; Tiesler, Nina Clara (eds.). Women, Soccer and Transnational Migration. Routledge. p. 26. ISBN 978-1135939380.

- Denmark was represented by a club, that also won the tournament. Stated in Danish DR2's TV-documentary about the 1971 event of the same kind

- "Da Danmark blev verdensmestre i fodbold – DRTV" – via www.dr.dk.

- "Women's Football – First ladies pave the way". FIFA.com.

- Jeanes, Ruth (10 September 2009). "Ruff Guide to Women & Girls Football". Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- McIntyre, Scott (17 July 2012). "Japan's second-class citizens the world's best". SBS. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Edwards, Elise (4 August 2011). "NOT A CINDERELLA STORY: THE LONG ROAD TO A JAPANESE WORLD CUP VICTORY". Stanford University Press. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Murray, Jeremy A.; Nadeau, Kathleen M. (15 August 2016). Pop Culture in Asia and Oceania. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3991-7.

- "Chinese Women's Super League launched to promote women's soccer[1]- Chinadaily.com.cn". www.chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "India – List of Women Champions". www.rsssf.com. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "Mike Ryan, The First Coach of the U.S. WNT Passes Away at 77". United States Soccer Federation. 24 November 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- "2003 WOMEN'S WORLD". ESPN.com. 10 July 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Bell, Jack (8 April 2002). "W.U.S.A. Returns With a Full Lineup". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- MANDELL, NINA. "WPS, second attempt at a professional women's soccer league in the U.S., officially folds after three seasons". nydailynews.com. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Goff, Steven (13 April 2013). "National Women's Soccer League aims to succeed where previous U.S. women's soccer leagues have failed". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Univision. "Women's soccer league in Mexico draws huge crowds". Univision (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- "The women's game's incessant growth". FIFA. 8 March 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "Dodd: Women's football deserves a blueprint for growth". FIFA. 12 May 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "FIFA Women's World Cup History". FIFA. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "50 facts about the FIFA Women's World Cup" (PDF). FIFA. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Women's Football" (PDF). FIFA. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- Gibson, Owen (8 September 2009). "Men's and women's football: a game of two halves". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "Football – England women 'refuse to sign' FA contracts in wage dispute". Eurosport. 8 January 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "No increase in women's sport coverage since the 2012 Olympics". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "Tide is rising but we are only at the beginning of a whole new ball game". Sunday Independent. 8 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "The incredible growth of women's soccer" (video). FIFA. 11 June 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- Gomez-Gonzalez, Carlos; Dietl, Helmut; Nesseler, Cornel (November 2019). "Does performance justify the underrepresentation of women coaches? Evidence from professional women's soccer". Sport Management Review. 22: 5. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2018.09.008.

- Stokkermans, Karel (23 July 2015). "Women's World Cup". Rsssf.com.

- "Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation — Women's FIFA Invitational Tournament 1988". Rsssf.com. 6 July 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- Plaschke, Bill (10 July 2009). "The spirit of 1999 Women's World Cup lives on". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Murphy, Melissa (2005). "HBO documentary features Hamm, U.S. soccer team". USA Today. The Associated Press. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- "England to go solo with 2012 Olympic team?". ESPNsoccernet. 29 May 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2009.

- "Coppa Europa per Nazioni (Women) 1969". Rsssf.com. 19 March 2001. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- "Inofficial European Women Championship 1979". Rsssf.com. 15 October 2000. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- "Copa Libertadores Femenina". Soccerway. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- Laverty, Glenn (1 June 2014). "Kelly Smith stars as Arsenal retain The FA Women's Cup". Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "Women's FA Cup: Wembley win may not benefit clubs financially". 31 July 2015 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- Prize money list on the FA website

- "Match Report: Spain–Japan, FIFA U-20 Women's World Cup France 2018". FIFA. 24 August 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "Pina-inspired Spain win maiden U-17 Women's World Cup title" (Press release). FIFA. 1 December 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- Christenson, Marcus (16 January 2004). "Soccer chief's plan to boost women's game? Hotpants". London: the Guardian. Retrieved 9 February 2007.

- "Women footballers blast Blatter". British Broadcasting Corporation. 16 January 2004. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- Tidey, Will (31 May 2013). "Sepp Blatter's Most Embarrassing Outbursts". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- "Football: Said and Done, The Observer (London); Sep 21, 2008; David Hills; p. 15". Guardian. 21 September 2008. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- "Iran's women footballers banned from Olympics because of Islamic strip". Guardian. London. 3 June 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- "Mahmoud Ahmadinejad blasts Fifa 'dictators' as Iranian ban anger rises". Guardian. London. 7 June 2011. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- Dehghanpisheh, Babak (17 July 2011). "Soccer's Headscarf Scandal in Iran". Newsweek. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- Homewood, Brian (5 July 2012). "Goal line technology and Islamic headscarf approved". Reuters.

- Alistair Potter (30 June 2011). "Cash-strapped Russian team to play in bikinis to bring back fans". Metro. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

Further reading

- David J. Williamson (1991). Belles of the ball: The Early History of Women's Association Football. R&D Associates. p. 100. ISBN 0-9517512-0-4. OCLC 24751810.

- Gail J Newsham (1997). In a League of Their Own! The Dick, Kerr Ladies 1917-1965. London: Scarlet Press. ISBN 1-85727-029-0. OCLC 40702553.

- Jean Williams (2003). A Game for Rough Girls?: a history of women's football in England. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26338-2.