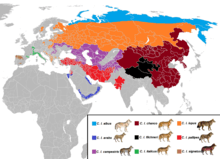

Wolf distribution

Wolf distribution is the species distribution of the wolf (Canis lupus). Originally, wolves occurred in Eurasia above the 12th parallel north and in North America above the 15th parallel north. However, deliberate human persecution has reduced the species' range to about one-third, because of livestock predation and fear of wolf attacks on humans. The species is now extirpated (made locally extinct) in much of Western Europe, in Mexico, and much of the United States. In modern history, the gray wolf occurs mostly in wilderness and remote areas, particularly in Canada, Alaska and the Northern United States, Europe and Asia from about the 75th parallel north to the 12th parallel north. Wolf population declines have been arrested since the 1970s, and have fostered recolonization and reintroduction in parts of its former range, due to legal protection, changes in land-use and rural human population shifts to cities. Competition with humans for livestock and game species, concerns over the danger posed by wolves to people, and habitat fragmentation pose a continued threat to the species. Despite these threats, because of the gray wolf's relatively widespread range and stable population, it is classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.[1]

Europe

Decline

Wolf populations strongly declined across Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries largely due to human persecution, and by the End of World War II in Europe they had been extirpated from all of Central Europe and almost all of Northern Europe.[2]

The extirpation of Northern Europe's wolves first became an organized effort during the Middle Ages, and continued until the late 19th century. In England, wolf eradication was enforced by legislation, and the last wolf was killed in the early 16th century during the reign of Henry VII (reigned 1485-1509). Wolves lasted longer in Scotland, where they sheltered in vast tracts of forest, which were subsequently burned down. Wolves managed to survive in the forests of Braemar and Sutherland until 1684. The extirpation of wolves in Ireland followed a similar course, with the last wolf believed to have been killed in 1786.[3] A wolf bounty was introduced in Sweden in 1647, after the extirpation of moose and reindeer forced wolves to feed on livestock. The Sami extirpated wolves in northern Sweden in organized drives. By 1960, few wolves remained in Sweden, because of the use of snowmobiles in hunting them, with the last specimen being killed in 1966. The gray wolf was extirpated in Denmark in 1772 and Norway's last wolf was killed in 1973. The species was decimated in 20th century Finland, despite regular dispersals from Russia. The gray wolf was only present in the eastern and northern parts of Finland by 1900, though its numbers increased after World War II.[4]

In Central Europe, wolves were dramatically reduced in number during the early 19th century, because of organized hunts and reductions in ungulate populations. In Bavaria, the last wolf was killed in 1847, and had disappeared from the Rhine regions by 1899.[4] In Switzerland, wolves were extirpated in the 20th century; they are naturally coming back from Italy since the 1990s.[5] In 1934, Nazi Germany became the first state in modern history to place the wolf under protection, though the species was already extirpated in Germany at this point.[6] The last free-living wolf to be killed on the soil of present-day Germany before 1945 was the so-called "Tiger of Sabrodt", which was shot near Hoyerswerda, Lusatia (then Lower Silesia) in 1904. Today, wolves have returned to the area.[7] Wolf hunting in France was first institutionalized by Charlemagne between 800–813, when he established the louveterie, a special corps of wolf hunters. The louveterie was abolished after the French Revolution in 1789, but was reestablished in 1814. In 1883, up to 1,386 wolves were killed, with many more by poison.[4]

In Eastern Europe, some wolves remained because of the area's contiguity with Asia and its large forested areas. However, Eastern European wolf populations were reduced to very low numbers by the late 19th century. Wolves were extirpated in Slovakia during the first decade of the 20th century and, by the mid-20th century, could only be found in a few forested areas in eastern Poland. Wolves in the eastern Balkans benefitted from the region's contiguity with the former Soviet Union and large areas of plains, mountains and farmlands. Wolves in Hungary occurred in only half the country around the start of the 20th century, and were largely restricted to the Carpathian Basin. Wolf populations in Romania remained largely substantial, with an average of 2,800 wolves being killed annually out of a population of 4,600 from 1955–1965. An all-time low was reached in 1967, when the population was reduced to 1,550 animals. The extirpation of wolves in Bulgaria was relatively recent, as a previous population of about 1,000 animals in 1955 was reduced to about 100–200 in 1964. In Greece, the species disappeared from the southern Peloponnese in 1930. Despite periods of intense hunting during the 18th century, wolves never disappeared in the western Balkans, from Albania to the former Yugoslavia. Organized persecution of wolves began in Yugoslavia in 1923, with the setting up of the Wolf Extermination Committee (WEC) in Kocevje, Slovenia. The WEC was successful in reducing wolf numbers in the Dinaric Alps.[4]

In Southern Europe, some wolves remained because of greater cultural tolerance of the species. Wolf populations only began declining in the Iberian Peninsula in the early 19th century, and was reduced by a half of its original size by 1900. Wolf bounties were regularly paid in Italy as late as 1950. Wolves were extirpated in the Alps by 1800, and numbered only 100 by 1973, inhabiting only 3–5% of their former Italian range.[4]

Recovery

The recovery of European wolf populations began after the 1950s, when traditional pastoral and rural economies declined and thus removed the need to heavily persecute wolves. By the 1980s, small and isolated wolf populations expanded in the wake of decreased human density in rural areas and the recovery of wild prey populations.[8]

The gray wolf has been fully protected in Italy since 1976, and now holds a population of over 1,269–1,800.[9] Italian wolves entered France's Mercantour National Park in 1993, and at least fifty wolves were discovered in the western Alps in 2000. By 2013 the 250 wolves in the Western Alps imposed a significant burden on traditional sheep and goat husbandry with a loss of over 5,000 animals in 2012.[10] There are approximately 2,000 wolves inhabiting the Iberian Peninsula, of which 150 reside in northeastern Portugal. In Spain, the species occurs in Galicia, Leon, and Asturias. Although hundreds of Iberian wolves are illegally killed annually, the population has expanded south across the river Duero and east to the Asturias and Pyrenees Mountains.[8]

.jpg)

In 1978, wolves began recolonising central Sweden after a 12-year absence, and have since expanded into southern Norway. As of 2020, the total number of Swedish and Norwegian wolves is estimated to be 450.[11] The gray wolf is protected in Sweden but with an 12% annual rate of poaching,[12] and partially controlled in Norway. The Scandinavian wolf populations owe their continued existence to neighbouring Finland's contiguity with the Republic of Karelia, which houses a large population of wolves. Wolves in Finland are protected only in the southern third of the country, and can be hunted in other areas during specific seasons,[8] though poaching remains common, with 90% of young wolf deaths being due to human predation, and the number of wolves killed exceeds the number of hunting licenses, in some areas by a factor of two. Furthermore, the decline in the moose populations has reduced the wolf's food supply.[13][14] Since 2011, the Netherlands, Belgium and Denmark have also reported wolf sightings presumably by natural migration from adjacent countries.[15][16] In 2016, a female wolf tracked 550 kilometers from a region southwest of Berlin to settle in Jutland, Denmark where male wolves had been reported in 2012 for the first time in 200 years.[17] Wolves have also commenced breeding in Lower Austria's Waldviertel region for the first time in over 130 years.[18]

Wolf populations in Poland have increased to about 800–900 individuals since being classified as a game species in 1976. Poland plays a fundamental role in providing routes of expansion into neighbouring Central European countries. In the east, its range overlaps with populations in Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and Slovakia. A population in western Poland expanded into eastern Germany and in 2000 the first pups were born on German territory.[19] In 2012, an estimated 14 wolf packs were living in Germany (mostly in the east and north) and a pack with pups has been sighted within 15 miles of Berlin;[20] the number increased to 46 packs in 2016.[21] The gray wolf is protected in Slovakia, though an exception is made for wolves killing livestock. A few Slovakian wolves disperse into the Czech Republic, where they are afforded full protection. Wolves in Slovakia, Ukraine and Croatia may disperse into Hungary, where the lack of cover hinders the buildup of an autonomous population. Although wolves have special status in Hungary, they may be hunted with a year-round permit if they cause problems.[8]

Romania has a large population of wolves, numbering 2,500 animals. The wolf has been a protected animal in Romania since 1996, although the law is not enforced. The number of wolves in Albania and North Macedonia is largely unknown, despite the importance the two countries have in linking wolf populations from Greece to those of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. Although protected, sometimes wolves are still illegally killed in Greece, and their future is uncertain. Wolf numbers have declined in Bosnia and Herzegovina since 1986, while the species is fully protected in neighbouring Croatia and Slovenia.[8]

Although wolf-dog hybridization in Europe has raised concern among conservation groups fearing for the gray wolf's purity, genetic tests show that introgression of dog genes into European gray wolf populations does not pose a significant threat. Also, as wolf and dog mating seasons do not fully coincide, the likelihood of wild wolves and dogs mating and producing surviving offspring is small.[22]

Asia

Historical range and decline

During the 19th century, gray wolves were widespread in many parts of the Holy Land east and west of the Jordan River. However, they decreased considerably in number between 1964 and 1980, largely because of persecution by farmers.[23] The species was not considered common in northern and central Saudi Arabia during the 19th century, with most early publications citing sources which involved animals either from southwestern Asir, northern rocky areas bordering Jordan, or areas surrounding Riyadh.[24]

The gray wolf's range in the Soviet Union encompassed nearly the entire territory of the country, being absent only on the Solovetsky Islands, Franz-Josef Land, Severnaya Zemlya, and the Karagin, Commander and Shantar Islands. The species was extirpated twice in Crimea, once after the Russian Civil War, and again after World War II.[25] Following the two world wars the Soviet wolf populations peaked twice, with 30,000 wolves being harvested annually out of a population of 200,000 during the 1940s, and 40,000–50,000 harvested during peak years. Soviet wolf populations reached a low around 1970, disappearing over much of European Russia. The population increased again by 1980 to about 75,000, with 32,000 being killed in 1979.[26] Wolf populations in northern Inner Mongolia declined during the 1940s, primarily because of poaching of gazelles, the wolf's main prey.[27] In British-ruled India, wolves were heavily persecuted because of their attacks on sheep, goats and children. In 1876, 2,825 wolves were bountied in the North-Western Provinces (NWP) and Bihar. By the 1920s, wolf eradication remained a priority in the NWP and Awadh. Overall, over 100,000 wolves were killed for bounties in British India between 1871 and 1916.[28]

Wolves in Japan were extirpated during the Meiji restoration period, in a campaign known as ōkami no kujo. The wolf was deemed a threat to ranching, which the Meiji government promoted at the time, and targeted via a bounty system and a direct chemical poisoning campaign inspired by the similar contemporary American campaign. The last Japanese wolf was a male killed on January 23, 1905 near Washikaguchi (now called Higashi Yoshiro).[29] The now-extirpated Japanese wolves were descended from large Siberian wolves, which colonized the Korean Peninsula and Japan, before it separated from mainland Asia, 20,000 years ago during the Pleistocene. During the Holocene, the Tsugaru Strait widened and isolated Honshu from Hokkaido, thus causing climatic changes leading to the extinction of most large-bodied ungulates inhabiting the archipelago. Japanese wolves likely underwent a process of island dwarfism 7,000–13,000 years ago in response to these climatological and ecological pressures. C. l. hattai (formerly native to Hokkaidō) was significantly larger than its southern cousin C. l. hodophilax, as it inhabited higher elevations and had access to larger prey, as well as a continuing genetic interaction with dispersing wolves from Siberia.[30]

Gray wolves had a wide historic range in China encompassing nearly all of mainland China, including southern China.[31] A systematic review by Wang et al. in 2016, found museum specimens from wolves from across China, in 13 provinces, including several in southern China - two specimens sampled from two southern Chinese provinces (Zhejiang and Fujian) in 1974, and one from southern Yunnan in 1985.[31] This study also reviewed more than 100 articles and found modern, recent records of gray wolves in every continental province of China between 1964 and the present except for three provinces - Tianjin, Jiangsu, and Fujian.[31] Wolves were recorded in South China (in Yunnan province) as late as 2011, and in the two southernmost provinces (Guangdong and Guangxi) in the year of 2000.[31] From these findings, the researchers concluded that wolves are still present across all parts of continental China.[31]

Modern range

There is little reliable data on the status of wolves in the Middle East, save for those in Israel and Saudi Arabia, though their numbers appear to be stable, and are likely to remain so. Throughout the Middle East, the species is only protected in Israel. Elsewhere, it can be hunted year-round by Bedouins. Israel's conservation policies and effective law enforcement maintain a moderately sized wolf population, which radiates into neighbouring countries, while Saudi Arabia has vast tracts of desert, where about 300–600 wolves live undisturbed.[32] The wolf survives throughout most of its historical range in Saudi Arabia, probably because of a lack of pastoralism and abundant human waste.[24] Turkey may play an important role in maintaining wolves in the region, because of its contiguity with Central Asia.[32] Although Turkish wolves have no legal protection, they may number about 7,000 individuals.[33] The mountains of Turkey have served as a refuge for the few wolves remaining in Syria. A small wolf population occurs in the Golan Heights, and is well protected by the military activities there. Wolves living in the southern Negev desert are contiguous with populations living in the Egyptian Sinai and Jordan.[32]

The northern regions of Afghanistan and Pakistan are important strongholds for the wolf. It has been estimated that there are about 300 wolves in approximately 60,000 km2 (23,000 sq mi) of Jammu and Kashmir in northern India, and 50 more in Himachal Pradesh. Overall, India supports about 800–3,000 wolves, scattered among several remnant populations. Although protected since 1972, Indian wolves are classed as endangered, with many populations lingering in low numbers or living in areas increasingly used by humans. Little is known of current wolf populations in Iran, which occurred throughout the country in low densities during the mid-1970s. Although present in Nepal and Bhutan, there is no information on wolves occurring there.[26]

Wolf populations throughout Northern and Central Asia are largely unknown, but are estimated in the hundreds of thousands based on annual harvests. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, continent-wide culling of wolves has ceased, and wolf populations have increased to about 25,000–30,000 animals throughout the former Soviet Union. In China and Mongolia, wolves are only protected in reserves. Mongolian populations have been estimated at 10,000–30,000, while the status of wolves in China is more fragmentary. The north has a declining population of an estimated 400 wolves, while Xinjiang and Tibet hold about 10,000 and 2,000 respectively.[34] In 2008, an authoritative reference stated that the gray wolf could be found across mainland China.[35]

In 2017, a comprehensive study found that the gray wolf was present across all of mainland China, both in the past and today. It exists in southern China, which refutes claims made by some researchers in the Western world that the wolf had never existed in southern China.[36][37] In 2019, a genomic study on the wolves of China included museum specimens of wolves from southern China that were collected between 1963-1988. The wolves in the study formed 3 clades: north Asian wolves that included those from northern China and eastern Russia, Himalayan wolves from the Tibetan Plateau, and a unique population from southern China. One specimen from Zhejiang province in eastern China shared gene flow with the wolves from southern China, however its genome was 12-14 percent admixed with a canid that may be the dhole or an unknown canid that predates the genetic divergence of the dhole. The wolf population from southern China is believed to be still existing in that region.[38]

North America

_%26_MSW3_(2005).png)

Historical range and decline

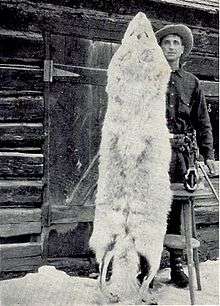

Originally, the gray wolf occupied all of North America north of about 20°N. It occurred all over the mainland, save for the southeastern United States, California west of the Sierra Nevada, and the tropical and subtropical areas of Mexico. Large continental islands occupied by wolves included Newfoundland, Vancouver Island, the southeastern Alaskan islands, and throughout the Arctic Archipelago and Greenland.[39] While Lohr and Ballard postulated that the gray wolf had never been present on Prince Edward Island,[40][41]:392 analysis of references to the island's native fauna in unpublished and published historical records has found that gray wolves were resident there at the time of the first French settlement in 1720. In his November 6, 1721 letter to the French Minister of the Marine, Louis Denys de La Ronde reported that the island was home to wolves "of a prodigious size", and sent a wolf pelt back to France to substantiate his claim. As the island was cleared for settlement, the gray wolf population may have been extirpated, or relocated to the mainland across the winter ice: the few subsequent wolf reports date from the mid-19th century and describe the creatures as transient visitors from across the Northumberland Strait.[41]:386

The decline of North American wolf populations coincided with increasing human populations and the expansion of agriculture. By the start of the 20th century, the species had almost disappeared from the eastern U.S., excepting some areas of the Appalachians and the northwestern Great Lakes Region. In Canada, the gray wolf was extirpated in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia between 1870 and 1921, and in Newfoundland around 1911. It vanished from the southern regions of Quebec and Ontario between 1850 and 1900. The gray wolf's decline in the prairies began with the extirpation of the American bison and other ungulates in the 1860s–70s. From 1900–1930, the gray wolf was virtually eliminated from the western U.S. and adjoining parts of Canada, because of intensive predator control programs aimed at eradicating the species. The gray wolf was extirpated by federal and state governments from all of the U.S. by 1960, except in Alaska and northern Minnesota. The decline in North American wolf populations was reversed from the 1930s to the early 1950s, particularly in southwestern Canada, because of expanding ungulate populations resulting from improved regulation of big game hunting. This increase triggered a resumption of wolf control in western and northern Canada. Thousands of wolves were killed from the early 1950s to the early 1960s, mostly by poisoning. This campaign was halted and wolf populations increased again by the mid-1970s.[39]

Modern range

The range of the species in North America today is mostly confined to Alaska and Canada, with populations also occurring in northern Minnesota, northern and central Wisconsin, Michigan's Upper Peninsula, and small portions of Washington, Idaho, northern Oregon, and Montana. A functional wolf population should exist in California by 2024 according to estimates by state wildlife officials.[42] Canadian wolves began to naturally recolonize northern Montana around Glacier National Park in 1979, and the first wolf den in the western U.S. in over half a century was documented there in 1986.[43] The wolf population in northwest Montana initially grew as a result of natural reproduction and dispersal to about 48 wolves by the end of 1994.[44] From 1995–1996, wolves from Alberta and British Columbia were relocated to Yellowstone National Park and Idaho. In addition, the Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) was reintroduced to Arizona and New Mexico in 1998. The gray wolf is found in approximately 80% of its historical range in Canada, thus making it an important stronghold for the species.[39]

Canada is home to about 52,000–60,000 wolves, whose legal status varies according to province and territory. First Nations residents may hunt wolves without restriction, and some provinces require licenses for residents to hunt wolves while others do not. In Alberta, wolves on private land may be baited and hunted by the landowner without requiring a license, and in some areas, wolf hunting bounty programs exist.[45][46] Large-scale wolf population control through poisoning, trapping and aerial hunting is also presently conducted by government-mandated programs in order to support populations of endangered prey species such as woodland caribou.[47]

In Alaska, the gray wolf population is estimated at 6,000–7,000, and can be legally harvested during hunting and trapping seasons, with bag limits and other restrictions. As of 2002, there are 250 wolves in 28 packs in Yellowstone, and 260 wolves in 25 packs in Idaho. The gray wolf received Endangered Species Act (ESA) protection in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan in 1974, and was reclassified from endangered to threatened in 2003. Reintroduced Mexican wolves in Arizona and New Mexico are protected under the ESA and, as of late 2002, number 28 individuals in eight packs.[48] A female wolf shot in 2013 in Hart County, Kentucky by a hunter was the first gray wolf seen in Kentucky in modern times. DNA analysis by Fish and Wildlife laboratories showed genetic characteristics similar to those of wolves in the Great Lakes Region.[49] In April 2019, the first wolf pups were born in California.[50]

See also

- List of gray wolf populations by country

- OR-7, a gray wolf being electronically tracked in the northwestern United States

References

- Boitani, L., Phillips, M. & Jhala, Y. (2018). "Canis lupus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2018. e.T3746A119623865. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T3746A119623865.en.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Randi, Ettore (2007). "Ch 3.4 – Population genetics of wolves (Canis lupus)". In Weiss, Steven; Ferrand, Nuno (eds.). Phylogeography of Southern European Refugia. Springer. pp. 118–121. ISBN 978-1-4020-49033.

- Hickey, Kieran (May 2003). "Wolf – forgotten Irish hunter" (PDF). Wild Ireland: 10–13. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2014.

- Mech & Boitani 2003, pp. 318–320

- Heinz Staffelbach, Manuel des Alpes suisses. Flore, faune, roches et météorologie (in French), Rossolis, 2009 (ISBN 978-2-940365-30-2). Also available in German: Heinz Staffelbach, Handbuch Schweizer Alpen. Pflanzen, Tiere, Gesteine und Wetter, Haupt Verlag, 2008 (ISBN 978-3-258-07638-6).

- Sax, Boria (2000). Animals in the Third Reich: Pets, Scapegoats, and the Holocaust, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 75, ISBN 0-8264-1289-0

- Verbreitung in Deutschland Archived April 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine at Wolf Region Lausitz . Retrieved October 12, 2013

- Mech & Boitani 2003, pp. 324–326

- Galaverni, Marco; Caniglia, Romolo; Fabbri, Elena; Milanesi, Pietro; Randi, Ettore (2016). "One, no one, or one hundred thousand: how many wolves are there currently in Italy?". Mammal Research. 61: 13–24. doi:10.1007/s13364-015-0247-8.

- Scott Sayare (September 3, 2013). "As Wolves Return to French Alps, a Way of Life Is Threatened". The New York Times. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

sheep and goat losses doubled in the past five years to nearly 6,000 in 2012

- "Fakta om varg". naturvardsverket.se. Environmental Protection Agency (Sweden). Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Poaching-related disappearance rate of wolves in Sweden was positively related to population size and negatively to legal culling". sciencedirect. Biological Conservation. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Juha Kauppinen (April 2008). "Susien määrä yllättäen vähentynyt", Suomen Luonto (in Finnish).

- "SS: Kuolleissa susissa vanhoja hauleja", Iltalehti (in Finnish), March 19, 2013.

- "The wolf returns: Call of the wild", The Economist, (December 22, 2012)

- "Det var en ulv" Archived December 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, (in Danish) Danish Nature Agency, (December 7, 2012)

- "Denmark Has A Wild Wolf Pack For The First Time In 200 Years". iflscience. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- "Wolves Are Breeding In Austria For First Time Since 1882". iflscience. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- Friedrich, Regina (February 2010). "Wolves in Germany". Translated by Kevin White. Goethe-Institut e. V., Online-Redaktion. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- Paterson, Tony (November 20, 2012). "Wolves close in on Berlin after more than a century". The Independent. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- "Raubtiere: In Deutschland leben 46 Wolfsrudel". Spiegel Online. September 23, 2016.

- Vilà, Carles; Wayne, Robert K. (1997). "Hybridization between Wolves and Dogs". Conservation Biology. 13 (1): 195–198. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1999.97425.x. JSTOR 2641580.

- Qumsiyeh, Mazin B. (1996). Mammals of the Holy Land. Texas Tech University Press, pp. 146–148, ISBN 0-89672-364-X

- Cunningham, P. L.; Wronski, T. (2010). "Arabian wolf distribution update from Saudi Arabia" (PDF). Canid News. 13: 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 21, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- Heptner, V.G. & Naumov, N.P. (1998). Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, SIRENIA AND CARNIVORA (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears). Science Publishers, Inc. USA. pp. 164–270. ISBN 1-886106-81-9.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Mech & Boitani 2003, p. 327

- Mech & Boitani 2003, p. 320

- Knight, John (2004). Wildlife in Asia: Cultural Perspectives, Psychology Press, pp. 219–221, ISBN 0-7007-1332-8

- Walker 2005

- Walker 2005, p. 41

- Lu WANG, Ya-Ping MA, Qi-Jun ZHOU, Ya-Ping ZHANG, Peter SAVOLAIMEN, Guo-Dong WANG. 2016. The geographical distribution of grey wolves (Canis lupus) in China: a systematic review[J]. Zoological Research, 37(6): 317-328.

- Mech & Boitani 2003, pp. 326–327

- Zuppiroli, Pierre; Donnez, Lise (2006). "An Interview with Ozgun Emre Can on the Wolves in Turkey" (PDF). WolfPrint. Vol. 26. UK Wolf Conservation Trust (UKWCT). pp. 8–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011.

- Mech & Boitani 2003, pp. 327–328

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2008). "Family Canidae". In Smith, A.T.; Xie, Y.; et al. (eds.). A Guide to the Mammals of China. Princeton University Press. pp. 416–418. ISBN 978-0691099842.

- Wang, L; Ma, Y. P.; Zhou, Q. J.; Zhang, Y. P.; Savolaimen, P.; Wang, G. D. (2016). "The geographical distribution of grey wolves (Canis lupus) in China: A systematic review". Zoological Research. 37 (6): 315–326. doi:10.13918/j.issn.2095-8137.2016.6.315. PMC 5359319. PMID 28105796.

- Larson, Greger; Larson, Greger (2017). "Reconsidering the distribution of gray wolves". Zoological Research. 38 (3): 115–116. doi:10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2017.021. PMC 5460078. PMID 28585433.

- Wang, Guo-Dong; Zhang, Ming; Wang, Xuan; Yang, Melinda A.; Cao, Peng; Liu, Feng; Lu, Heng; Feng, Xiaotian; Skoglund, Pontus; Wang, Lu; Fu, Qiaomei; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2019). "Genomic Approaches Reveal an Endemic Subpopulation of Gray Wolves in Southern China". IScience. 20: 110–118. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2019.09.008. PMC 6817678. PMID 31563851.

- Paquet, P.; Carbyn, L.W. (2003). "Gray wolf Canis lupus and allies". In Feldhamer, George A.; Chapman, J.A. (eds.). Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation. JHU Press. pp. 482–510. ISBN 0-8018-7416-5.

- Lohr, C.; Ballard, W. B. (1996). "Historical Occurrence of Wolves, Canis lupus, in the Maritime Provinces". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 110: 607–610.

- Sobey, Douglas G. (2007). "An Analysis of the Historical Records for the Native Mammalian Fauna of Prince Edward Island". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 121 (4): 384–396. doi:10.22621/cfn.v121i4.510.

- La Ganga, Maria L. (May 14, 2014) "OR7, the wandering wolf, looks for love in all the right places" Los Angeles Times

- The Reintroduction of Gray Wolves to Yellowstone National Park and Central Idaho: Final Environmental Impact Report (PDF) (Report). USFWS. 1994. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- "Gray Wolf History". Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks. Retrieved February 9, 2014.

- Government of Alberta. "Alberta Hunting Regulations". Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- "2013-03-27 AWA News Release: Alberta Government has Lost Control of Wolf Management". Archived from the original on July 30, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- Struzik, Ed (October 27, 2011). "Killing Wolves: A Product of Alberta's Big Oil and Gas Boom".

- Mech & Boitani 2003, pp. 321–324

- Russ McSpadden (August 19, 2013). "Wild Wolf in Kentucky, First in 150 Years, Killed by Hunter". Earth First! News. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- Wolf Management Update California Department of Fish and Wildlife April - June 2019

Bibliography

- Walker, Brett L. (2005). The Lost Wolves Of Japan. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98492-6.