William Massey

William Ferguson Massey PC (26 March 1856 – 10 May 1925), commonly known as Bill Massey, was a politician who served as the 19th Prime Minister of New Zealand from May 1912 to May 1925. He was the founding leader of the Reform Party, New Zealand's second organised political party, from 1909 until his death.

William Ferguson Massey | |

|---|---|

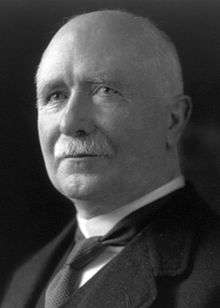

William Massey in 1919 | |

| 19th Prime Minister of New Zealand | |

| In office 10 July 1912 – 10 May 1925† | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Governor-General | John Dickson-Poynder Arthur Foljambe John Jellicoe Charles Fergusson |

| Preceded by | Thomas Mackenzie |

| Succeeded by | Sir Francis Bell |

| 5th Leader of the Opposition | |

| In office 11 September 1903 – 10 July 1912 | |

| Deputy | James Allen |

| Preceded by | William Russell |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Ward |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 26 March 1856 Limavady, County Londonderry, Ireland, UK |

| Died | 10 May 1925 (aged 69) Wellington, New Zealand |

| Political party | None until February 1909 Reform |

| Spouse(s) | Christina Allan Paul

( m. 1882) |

| Children | 7, including Walter and Jack |

| Parents | John Massey Marianne Ferguson |

| Relatives | Stan Goosman (nephew) |

Massey was born in County Londonderry in Ireland (now Northern Ireland). After migrating to New Zealand in 1870, Massey farmed near Auckland (earning his later nickname, Farmer Bill) and assumed leadership in farmers' organisations. He entered parliament in 1894 as a conservative, and from 1894 to 1912 was a leader of the conservative opposition to the Liberal ministries of Richard Seddon and Joseph Ward. Massey became the first Reform Party Prime Minister after he led a successful motion of no confidence against the Liberal government. Throughout his political career Massey was known for the particular support he showed for agrarian interests, as well as his opposition to organised labour. He pledged New Zealand's support for Britain during the First World War.

Massey led his Reform Party through four elections, although only the 1919 election was a decisive victory over all other parties. Following increasingly poor health in his fourth term, Massey died in office. After Richard Seddon, he is the second-longest-serving Prime Minister of New Zealand.

Early life

Massey was born in 1856 into a Protestant farming family, and grew up in Limavady, County Londonderry in Ireland. His father John Massey and his mother Marianne (or Mary Anne) née Ferguson were tenant farmers, who also owned a small property. His family arrived in New Zealand on 21 October 1862 on board the Indian Empire[1] as Nonconformist settlers,[2] although Massey remained in Ireland for a further eight years to complete his education. After arriving on 10 December 1870 on the City of Auckland, Massey worked as a farmhand for some years before acquiring his own farm in Mangere, south Auckland, in 1876.[3] In 1882 Massey married his neighbour's daughter, Christina Allan Paul. They had seven children.[4]

Early political career

Massey gradually became more prominent in his community. This was partly due to his civic involvement in the school board, the debating society,and farming associations. Because of his prominence in these circles, he became involved in political debate, working on behalf of rural conservatives against the Liberal Party government of John Ballance. William Massey was a member of the Orange Order, Oddfellows, and freemasons,[5] and espoused British Israelite ideas.[6]

In 1893 Massey stood as a candidate in the general election in the Franklin electorate, losing to the Liberal candidate, Benjamin Harris.[4] In early 1894 he was invited to contest a by-election in the neighbouring electorate of Waitemata, and was victorious. In the 1896 election he stood for the Franklin electorate, which he represented until he died in 1925.[7]

Opposition

| New Zealand Parliament | ||||

| Years | Term | Electorate | Party | |

| 1894–1896 | 12th | Waitemata | Independent | |

| 1896–1899 | 13th | Franklin | Independent | |

| 1899–1902 | 14th | Franklin | Independent | |

| 1902–1905 | 15th | Franklin | Independent | |

| 1905–1908 | 16th | Franklin | Independent | |

| 1908–1909 | 17th | Franklin | Independent | |

| 1909–1911 | Changed allegiance to: | Reform | ||

| 1911–1914 | 18th | Franklin | Reform | |

| 1914–1919 | 19th | Franklin | Reform | |

| 1919–1922 | 20th | Franklin | Reform | |

| 1922–1925 | 21st | Franklin | Reform | |

Massey joined the ranks of the (mostly conservative) independent MPs opposing the Liberal Party, led by Richard Seddon. They were poorly organised and dispirited, and had little chance of unseating the Liberals. William Russell, the Leader of the Opposition, was able to command only 15 votes. Massey brought increased vigour to the conservative faction and became opposition whip.[8]

By June 1900, following a heavy defeat at the 1899 general election, the opposition strength fell considerably. The conservative MPs could not agree on a new leader after holding their first caucus of the session. For over two years the conservatives were virtually leaderless and many despaired of ever toppling the Liberal Party. Massey, as chief whip, informally filled the role as leader and eventually succeeded Russell as Leader of the Opposition formally in September 1903.[9]

As leader, the conservatives rallied for a time, though support for the Liberals increased markedly during the Second Boer War, leaving the conservatives devastated at the 1902 general election. Massey's political career survived the period: despite a challenge by William Herries, he remained the most prominent opponent to the Liberal Party.[4]

After Seddon's death the Liberals were led by Joseph Ward, who proved more vulnerable to Massey's attacks. In particular, Massey made gains by claiming that alleged corruption and cronyism within the civil service was ignored or abetted by the Liberal government. His conservative politics also benefited him when voters grew concerned about militant unionism and the supposed threat of socialism.[4]

Reform Party

In February 1909,[10] Massey announced the creation of the Reform Party from his New Zealand Political Reform League. The party was to be led by him and backed by his conservative colleagues.

In the 1911 election the Reform Party won more seats than the Liberal Party but did not gain an absolute majority. The Liberals, relying on support from independents who had not joined Reform, were able to stay in power until the following year, when they lost a vote of confidence.

Prime Minister

Massey was sworn in as Prime Minister on 10 July 1912. Two days later it was reported in the press on 12 July that he had accepted the appointment of Honorary Commandant of the Auckland District of the Legion of Frontiersmen. Some members of the Reform Party grew increasingly frustrated at Massey's dominance of the party. He earned the enmity of many workers with his harsh response to miners' and waterfront workers' strikes in 1912 and 1913. The use of force to deal with the strikers made Massey an object of hatred for the emerging left-wing, but conservatives (many of whom believed that the unions were controlled by the far left) generally supported him, saying that his methods were necessary. His association with the Legion of Frontiersmen assisted him greatly during this period as a number of mounted units, including Levin Troop, rode to Wellington in mufti and assisted as Special Constables. In the Levin Troop was a young Bernard Freyberg, who would shortly earn the Victoria Cross near Beaumont Hamel.

Amongst the first Acts enacted by Massey's government was one that "enabled some 13,000 Crown tenants to purchase their own farms."[11]

First World War

All we are and all we have is at the disposal of the British Government.

— Cable from Massey to the British Government, 1914[11]

.jpg)

The outbreak of the First World War diverted attention from these matters. The 1914 election left Massey and his political opponents stalemated in parliament, with neither side possessing enough support to govern effectively. Massey reluctantly invited Joseph Ward of the Liberals to form a war-time coalition, created in 1915. While Massey remained Prime Minister, Ward gained de facto status as joint leader. Massey and Ward travelled to Britain several times, both during and after the war, to discuss military co-operation and peace settlements. During his first visit, Massey visited New Zealand troops, listening to their complaints sympathetically. This angered some officials, who believed that Massey undermined the military leadership by conceding (in contrast to the official line) that conditions for the troops were unsatisfactory. The war reinforced Massey's strong belief in the British Empire and New Zealand's links with it. He attended the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and signed the Treaty of Versailles on behalf of New Zealand.[12] Although turning down knighthoods and a peerage, he accepted appointment as a Grand Officer of the Order of the Crown (Belgium) from the King of Belgium in March 1921 and a Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour by the President of France in October 1921.[13]

Coalition with the Liberals

.jpg)

Partly because of the difficulty in obtaining consensus to implement meaningful policies, the coalition government had grown increasingly unpopular by the end of the war. Massey was particularly worried by the rise of the Labour Party, which was growing increasingly influential. Massey also found himself fighting off criticism from within his own party, including charges that he was ignoring rural concerns. He dissolved the coalition in 1919, and fought both the Liberals and Labour on a platform of patriotism, stability, support for farmers, and a public works program. He successfully gained a majority.

Immigration

The Immigration Restriction Amendment Act of 1920 aimed to further limit Asian immigration into New Zealand by requiring all potential immigrants not of British or Irish parentage to apply in writing for a permit to enter the country. The Minister of Customs had the discretion to determine whether any applicant was "suitable." Prime Minister William Massey asserted that the act was "the result of a deep seated sentiment on the part of a huge majority of the people of this country that this Dominion shall be what is often called a 'white' New Zealand."[14]

The Red Scare

According to New Zealand historian Tony Wilson, Massey was known for his anti-Bolshevik and anti-Soviet sentiments. He disliked domestic socialist elements like the "Red Feds", the predecessor to the New Zealand Federation of Labour, and the New Zealand Labour Party. As Prime Minister, Massey was opposed to Communist influence. He regarded the Red Terror (1919–20) in the Soviet Union, which followed the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, as proof of the "inherently oppressive orientation" of socialism. In response to the Red Scare the government passed the War Regulations Continuance Act, which continued wartime emergency regulations including censorship. This led to a ban on Communist-oriented literature, which continued to 1935.[15]

1922 election

Economic problems lessened support for Reform. In the 1922 election Massey lost his majority, and was forced to negotiate with independents to keep his government alive. He was also alarmed by the success of Labour, which was now only five seats behind the Liberals. He began to believe that the Liberals would eventually disappear, with their supporters being split, the socially liberal wing to Labour and the economically liberal wing to Reform. He set about trying to ensure that Reform's gain would be the greater.

In 1924 cancer forced him to relinquish many of his official duties, and the following year he died. The Massey Memorial was erected as his mausoleum in Wellington, paid for mostly by public subscription. Massey University is named after him, the name chosen because the university had a focus on agricultural science, matching Massey's own farming background.[4]

Honours

.svg.png)

Family

His widow, Christina, was awarded the GBE in 1926, one year after his death.[16]

Two of his sons became Reform MPs: Jack (1885–1964), who represented his father's Franklin electorate from 1928 to 1935, and from 1938 to 1957 for National; and Walter William (1882–1959), who represented Hauraki from 1931 to 1935.

His son Frank George Massey (1887–1975) enlisted in World War I, and transferred to the British Expeditionary Force where he commanded a battalion as a Major.[17]

References

- "Port of Onehunga". Daily Southern Cross. XVIII (1638). 21 October 1862. p. 2.

- 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Oxford DNB". Oxford DNB. 10 May 1925. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- Gustafson, Barry. "Massey, William Ferguson". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- "Massey, William Ferguson – Biography – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

-

Reynolds, David (2014). The Long Shadow: The Legacies of the Great War in the Twentieth Century. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 108. ISBN 9780393088632. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

Massey's British Israelite philosophy was extreme, not to say eccentric[...].

- Scholefield, Guy (1950) [First ed. published 1913]. New Zealand Parliamentary Record, 1840–1949 (3rd ed.). Wellington: Govt. Printer. p. 126.

- Wilson 1985, p. 279.

- Wilson 1985, p. 282.

- "The Reform Party". The Evening Post. LXVVII (36). 12 February 1909. p. 8. Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Allen, Sam (1985), To Ulster's Credit, Killinchy, UK, p. 116

- "New Zealand Prime Minister signs Treaty of Versailles". NZHistory. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- M. Brewer, 'New Zealand and the Légion d'honneur: Officiers, Commandeurs and Dignites', The Volunteers: The Journal of the New Zealand Military Historical Society, 35(3), March 2010, p.136.

- New Zealand Parliamentary Debates, 14 September 1920, p. 905.

- Wilson, Tony (2004). "Chapter 6: Defining the Red Menace". In Trapeznik, Alexander (ed.). Lenin's Legacy Down Under. Otago University Press. pp. 101–02. ISBN 1-877276-90-1.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 August 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Harper, Glyn (2019). For King and Other Countries. North Shore, Auckland: Massey University University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-9951029-9-6.

Further reading

- Constable, H.J. (1925), From ploughboy to premier: a new life of the Right Hon. William Ferguson Massey, P.C, London: John Marlowe Savage & Co.

- Farland, Bruce (2009), Farmer Bill: William Ferguson Massey & the Reform Party, Wellington: First Edition Publishers.

- Gardner, William James (1966), "MASSEY, William Ferguson", An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand, edited by A. H. McLintock, retrieved 24 April 2008

- Gardner, William J. "The Rise of W. F. Massey, 1891–1912", Political Science (March 1961) 13: 3–30; and "W. F. Massey in Power", Political Science (Sept. 1961), 3–30.

- Gustafson, Barry, "Massey, William Ferguson 1856–1925", Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, retrieved 24 April 2008

- Massey, D. Christine (1996), The life of Rt. Hon. W.F. Massey P.C., L.L.D. : Prime Minister of New Zealand, 1912–1925, Auckland, [N.Z.]: D.C. Massey

- Scholefield, Guy H. (1925), The Right Honourable William Ferguson Massey, M.P., P.C., Prime Minister of New Zealand, 1912–1925: a personal biography, Wellington, [N.Z.]: Harry H. Tombs

- Watson, James, and Lachy Paterson, eds. A Great New Zealand Prime Minister? Reappraising William Ferguson Massey (2010), essays by scholars

- Watson, James. W.F. Massey: New Zealand (2011), short scholarly biography; emphasis on Paris Peace Conference of 1919 excerpt

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Massey. |

- . . Dublin: Alexander Thom and Son Ltd. 1923. p. – via Wikisource.

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thomas Mackenzie |

Prime Minister of New Zealand 1912–1925 |

Succeeded by Francis Bell |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by William Herries |

Minister of Railways 1919–1922 |

Succeeded by David Guthrie |

| New Zealand Parliament | ||

| Preceded by Richard Monk |

Member of Parliament for Waitemata 1894–1896 |

Succeeded by Richard Monk |

| Preceded by Benjamin Harris |

Member of Parliament for Franklin 1896–1925 |

Succeeded by Ewen McLennan |