William Kelly Harrison Jr.

William Kelly Harrison Jr. (September 7, 1895 – May 25, 1987) was a highly decorated officer in United States Army with the rank of Lieutenant General. A graduate of the West Point Military Academy, he rose through the ranks to Brigadier general during World War II and distinguished himself in combat several times, while served as Assistant Division Commander, 30th Infantry Division during Normandy Campaign or Battle of the Bulge. Harrison was decorated with Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest decoration of the United States military for bravery in combat, for his actions during the Operation Cobra.[1][2]

William Kelly Harrison Jr. | |

|---|---|

William K. Harrison Jr as Major general | |

| Nickname(s) | "Billy" |

| Born | September 7, 1895 Washington, D.C. |

| Died | May 25, 1987 (aged 91) Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1917–1957 |

| Rank | |

| Service number | 0-5279 |

| Unit | |

| Commands held | U.S. Caribbean Command 9th Infantry Division 2nd Infantry Division |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II

|

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross Distinguished Service Medal (2) Legion of Merit Silver Star Bronze Star Medal (2) Purple Heart |

| Relations | William Kelly Harrison (father) |

| Other work | President, Officers' Christian Fellowship |

Following the War, Harrison remained in the Army and after several stateside assignments, he was ordered to Far East, where he served as head of the United Nations Command armistice delegation in the Korean War. He participated in the truce talks, which concluded with the signing of the Korean Armistice Agreement on July 27, 1953. Harrison completed his career as Commanding general, U.S. Caribbean Command in early 1957.[3][4][5]

Early career

William K. Harrison Jr. was born on September 7, 1895 in Washington, D.C. as the son of Naval officer and future Medal of Honor recipient, William Kelly Harrison and his wife Kate Harris. He was a direct descendant of President William Henry Harrison. Following high school, William Jr. received an senatorial appointment from Texas to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York in May 1913.[6][2][5]

He was a member of the class, which produced more than 55 future general officers including two Army Chiefs of Staff (Joseph L. Collins and Matthew B. Ridgway). Among his classmates were: Clare H. Armstrong, Rex W. Beasley, Robert M. Bathurst, Henry A. Barber Jr., William O. Butler, Theodore E. Buechler, Homer C. Brown, Aaron Bradshaw Jr., John T. Bissell, Mark W. Clark, John T. Cole, Miles A. Cowles, Gerald A. Counts, Norman D. Cota, Joseph L. Collins, John W. Coffey, James A. Code Jr., John M. Devine, William F. Daugherty, William W. Eagles, Charles H. Gerhardt, Theodore L. Futch, Robert W. Hasbrouck, Arthur M. Harper, Ernest N. Harmon, Horace Harding, Milton B. Halsey, Augustus M. Gurney, Edwin J. House, Joel G. House, Charles S. Kilburn, Laurence B. Keiser, Harris Jones, Harold R. Jackson, Frederick A. Irving, Harris M. Melasky, William C. McMahon, John T. Murray, Charles L. Mullins Jr., Bryant E. Moore, Daniel Noce, Harold A. Nisley, Matthew B. Ridgway, William O. Reeder, Onslow S. Rolfe, Thomas D. Stamps, Willis R. Slaughter, Stephen H. Sherrill, Herbert N. Schwarzkopf, Albert C. Smith, Joseph P. Sullivan, Edward W. Timberlake, George D. Wahl, George F. Wooley Jr., Sterling A. Wood, Raymond E. S. Williamson, Robert A. Willard and George H. Weems.[6][3]

Harrison graduated with Bachelor of Science degree on April 20, 1917, shortly following the United States entry into World War I, and was commissioned second lieutenant in the Cavalry branch. He was subsequently ordered to Camp Lawrence J. Hearn, California, where he joined 1st Cavalry Regiment.[6]

He was subsequently ordered with the regiment to Douglas, Arizona, from which his unit participated in the guard duties on the Mexican Border. Harrison reached consecutively the ranks of first lieutenant and Captain and returned to West Point Military Academy as an Instructor of French and Spanish languages. While in this capacity, he also completed advanced languages courses in French and Spanish.[6]

Harrison was later transferred to the 7th Cavalry Regiment at Fort Bliss, Texas and served with that unit until early 1923, when he was ordered to Washington, D.C. for duty on the staff of Army War College. He was promoted to Major during his service there and left for the Philippines in 1925, where he was attached to the 26th Cavalry Regiment (Philippine Scouts) at Camp Stotsenburg on Luzon.[6]

Following his return stateside in 1932, Harrison was attached to the 7th Cavalry Regiment at Fort Riley, Kansas. While stationed at Fort Riley, he completed advanced course at Army Cavalry School there and served on the Cavalry Board and as Troop Commander with 9th Cavalry Regiment.[6]

Harrison was ordered to the Army Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas in June 1936 and graduated one year later. He then joined the faculty of the school and served as an instructor of tactics until September 1937, when he was ordered to the Army War College for instruction.[6]

He graduated in July 1938 and joined the 6th Cavalry Regiment at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. Harrison remained in that assignment until August 1939, when he was attached to War Plans Division, War Department General Staff in Washington, D.C. While in this capacity, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel on July 1, 1940.[6][4]

World War II

Stateside service

Following the United States entry into World War II, Harrison was promoted to the temporary rank of Colonel on December 11, 1941, just four days after Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. He was appointed Deputy Chief of Strategy & Policy Group, War Plans Division, War Department General Staff and also was given additional duty at General George C. Marshall's Committee on Allocation of Responsibilities which was given the job of figuring out a reorganization of the Army High command. For his service in this capacity, Harrison was promoted to the temporary rank of Brigadier general on June 26, 1942.[1][6][4][5]

He was subsequently ordered to Camp Butner, North Carolina, where he was attached to the 78th Infantry Division under Major general Edwin P. Parker Jr. as Assistant Division Commander. Harrison then participated in the training of replacements for units serving overseas and suffered minor injury on an obstacle course in December 1942. While recuperating, he received a telephone call from Major general Leland S. Hobbs, commanding general, 30th Infantry Division, informing him about his new assignment with Hobbs division.[1][6][2][4]

Harrison was replaced by Brigadier general John K. Rice and appointed Assistant Division Commander under Hobbs, who tasked him with organization of the 30th Infantry Division's training at Camp Blanding, Florida. Harrison and Hobbs had know each other from West Point, where Hobbs was a member of Class 1915 and also were in the same class at the Army Command and General Staff School in 1937.[1][4]

Billy Harrison had almost no respect for Hobbs as a leader of the troops. From Harrison's point of view, Hobbs violated every principle of leadership except one: He demanded obedience and gave it to his superiors. But in almost every other aspects - from training and disciplining men to planning battle operations in the field. In short, Harrison described Hobbs as being "stricly [sic?] a Barracks soldier", who accustomed himself to applause.[4][5]

Despite this, Harrison remained loyal to Hobbs, who never received anything than support from his Assistant Division Commander. On the other hand, Harrison benefited from Hobbs's apparent weakness, when he had the opportunity to be with his men during the training and later in combat.[4]

Harrison participated in the training of his troops for the upcoming Tennessee Maneuvers in September-November 1943, where 30th Division showed considerable alertness and skills. Following the maneuvers, the division moved to Camp Atterbury, Indiana, where it concentrated on preparation for movement overseas.[4][5]

Overseas duty

Harrison led divisional advanced party overseas by the end of January 1944 and spent several next months with intensive training in England. The 30th Infantry Division departed for France in June that year and landed at Omaha Beach, Normandy on June 11, 1944. Harrison participated in the combats at Vire-et-Taute Canal and on Vire River and quickly won the admiration of his troops by accompanying them on the front lines with M3 submachine gun in hand. He also spent a first night in France in the trench with combat troops.[1][6][3][4]

On July 25, 1944, the 30th Infantry Division still participated in the combats near Saint-Lô, which it secured few days earlier. The Division was subsequently scheduled to participate in Operation Cobra, an offensive with intention to advance into Brittany. The offensive was to begin with a major saturation bombing of the enemy with the troops then moving in afterward, but due to the inaccurate plane navigation, planes bombed erroneously their own men. More than 600 of the men had been hit, many killed, including lieutenant general Lesley J. McNair, Commander of Army Ground Forces.[4]

Even Harrison's command group was located in the rear, he returned deliberately to the forward area shortly before the bombing began. He was thrown down by the blast of German Artillery fire, but was unharmed. Realizing that the success of the entire operation depended on the 30th Infantry Division carrying out its mission, Harrison began analyzing the situation and found out, that divisional Sherman tanks were totally disorganized and demoralized infantry was spread in the area. Moreover commanding officer of 120th Infantry Regiment, Colonel Hammond D. Birks was located somewhere in the forward area and his jeep was knocked out.[4]

Harrison ordered commander to get his tanks in battle formation and get ready for action and evacuated Colonel Birks to safety. He took soldier with bazooka through the hedgerow and ordered him to attack the German tank nearby. The soldier had hit German tank several times, but panicked and ran into the open, where he was killed. Harrison crawled back and came upon four American tanks in a neighboring field, who were waiting out the enemy shelling with their hatches shut tight. He climbed on the commander's tank and forced the crew to open the hatch by beating the tank's turret, subsequently ordering the general attack, which was successful. For his heroism in action, he was decorated with Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest decorations of the United States military for valor in combat.[7][8][4]

Harrison then participated in the Battle of Mortain, German drive to Avranches in mid-August 1944 and 30th Division clashed with elite 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler. The 30th Division then advanced through Belgium and Harrison distinguished himself again on September 2, 1944, while leading the Task Force of his division.[4]

He was riding with the forward elements of his Task Force heading to Rumilly, when his column was ambushed by enemy tanks. The Harrison's jeep was hit in the radiator and he was struck by enemy 75mm tank shell, hitting him to right shoulder, arm and leg. Harrison escaped from the damaged vehicle and hit the ditch, where he immediately dispatched his aide and driver to contact the next ranking officer in order that he might continue the advance. He did not mention his wounds, which were not visible due to his raincoat and crawled approximately 600 yards to the rear of the column in order to give further instructions for continuing the mission.[8][4]

Harrison fainted momentarily due to his wounds, but refused to be evacuated until he had contacted his subordinates and instructed them in the continuation of the attack. By the time, General Hobbs arrived and following a discovery of Harrison's wounds, he ordered his evacuation. For bravery in action, he was decorated with Silver Star and also received Purple Heart for wounds, which he was most proud of.[7][6][4][5]

He spent a week in First Army Hospital in Versailles and rejoined his division in Belgian town of Tongres, where the division's progress was halted due to fuel shortages and quagmire roads. The 30th Division then proceeded to the Netherlands, where liberated town of Kerkrade on September 25, 1944 and advanced to Germany, where took part in the combats on the Siegfried Line and subsequently in the battle of heavily defended city of Aachen on October 2.[4]

The 30th Infantry Division was ordered for rest and refit to the rear by the end of November 1944 and transferred to the Ninth United States Army under lieutenant general William H. Simpson. Harrison was tasked by Simpson himself to conduct a refresher course for all infantry and artillery commanders in the Ninth United States Army, down to the battalion level. Harrison lectured the tactics employed by his command in taking of several towns and then took the entire class to the field trip to Sankt Jöris near Aachen, where artillery and tanks were set up to demonstrate how they had been used in the attack there.[4]

Harrison and 30th Division returned to the frontlines following the launch of German massive offensive in Ardennes on December 17, 1944 and participated in the combats in Malmedy-Stavelot area. Hobbs tasked Harrison with the command of Task Force, consisting of 119th Infantry Regiment, which later repelled German assault at La Gleize. Harrison and his task force destroyed or captured 178 enemy armored vehicles, including 39 tanks.[4]

He was out of action during January 1945, when he suffered an infection requiring surgery. Following his return at the beginning of February 1945, Harrison was visited by General William H. Simpson, Commanding general, Ninth United States Army, who presented him with Army Distinguished Service Medal for his previous service with the War Plans Division, War Department General Staff, where he proposed new concept of organization.[6][4]

During March 1945, the 30th Division was located in the rear for rest and refit and conducted training for next deployment. Harrison took part in the crossing of Rhine River on March 23, and advanced further to Germany. After taking Hamelin and Braunschweig at the beginning of April 1945, the 30th Division Task Force under Harrison's command discovered two large groups of Hungarian Jews Women at Teutoburg Forest.[4]

On April 13, 1945, Harrison participated in the efforts to save 2,400 prisoners from Neuengamme concentration camp subcamp at Farsleben, whom they found locked in the train boxcars. The 30th Division then proceeded eastward and halted its advanced on Elbe River at Grunewald linking up with Soviet forces.[4]

For his service with 30th Infantry Division, Harrison received Legion of Merit and two Bronze Star Medals. The Allies bestowed him with several decorations including: Legion of Honour, Croix de Guerre with Palm by France, Distinguished Service Order by Great Britain, Order of Orange-Nassau by the Netherlands and Order of the Red Banner by Soviet Union.[7][6][4][5]

Postwar service

Harrison then participated in the occupation duty in Germany in Magdeburg until June 1945, when he was appointed acting Commanding general, 2nd Infantry Division located between Prague and Pilsen, Czechoslovakia. He returned to the United States by the end of July and commanded the Second division during the preparations for combat deployment to the Pacific area.[1][3][4]

He was relieved by Major General Edward M. Almond in September 1945 and assumed duty as his Assistant Division Commander. Due to surrender of Japan, the deployment to Pacific was canceled and Harrison served with the 2nd Division at Camp Swift, Texas until April 1946. Harrison was then appointed Commanding general, Camp Carson, Colorado, where he was responsible for the demobilization of troops returning from war zones in Europe and Pacific.[1][6][3][4]

In November 1946, Harrison was reverted to the his permanent rank of colonel and ordered to Japan, where he was attached to the General Headquarters of Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers under General Douglas MacArthur as Executive for Administrative Affairs and Reparations. While in this capacity, he collaborated closely with General MacArthur and was responsible for the restoration of Japanese economy as rapidly as possible.[1][2][3][4]

He remained in this capacity until January 1947, when he was appointed Commanding Officer, General Headquarters, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and also held additional duty as Executive Officer of Far East Command.[1][4]

Harrison was promoted again to brigadier general on January 24, 1948 and appointed Chief of Reparations Section at the headquarters of Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers and held this assignment until December 1948, when he was ordered back to the United States.[1][4]

He was subsequently appointed Chief of Armed Forces Information & Education Division, Department of the Army in Washington, D.C. and was promoted to major general on March 11, 1949. While in this capacity, Harrison was responsible for the propaganda and university extension courses. He didn't like that job and following the outbreak of Korean War, he applied to be assigned for a field command, hoping that Army Chief of Personnel, Matthew B. Ridgway, who was his friend and West Point classmate, would help him.[1][4]

Unfortunately, Ridgway couldn't help him at the time and offered him post as Commanding General of Fort Dix, New Jersey with additional duty as Commanding General 9th Infantry Division. Harrison accepted the offer in September 1950 and was responsible for the training of replacements for troops both in Europe and Korea. During sixteen-week training cycles, he had to transform young men into effective soldiers, but his methods were not met with understanding by some of the recruits parents and also with some unfavorable press.[3][4]

The night marches and forced sixteen-mile marches with packs caused complaints to congressmen. When the father of one recruit was invited to spend a week at the barracks with his son, he changed his mind and upon returning home, he wrote a second letter to the editor of the newspaper, withdrawing all his criticism.[4]

Harrison also ordered total racial integration of living accommodations at Fort Dix. It should be mentioned that he was no racist, but neither was he a civil rights activist. He did that because he needed his barracks to run in a more efficient manner. The barracks for white recruits were overcrowded and the ones for African Americans were half empty. The training was also racially integrated by Harrison.[4][5]

Korean War

Harrison was finally ordered to Korea in December 1951 and appointed Deputy Commander, Eighth United States Army under General James Van Fleet, whom he respected as combat troop leader. After reporting to general Van Fleet, Harrison inspected every 8th Army's combat division located on the Jamestown Line (including American, British Commonwealth, South Korean or United Nations troops) from Yellow Sea to the Sea of Japan.[6][4]

He gained awareness of the situation on the front, terrain and enemy positions, but there were no major military operations, just stalemate. The North Koreans and U.N. troops were located on the Jamestown Line and truce talks between United Nations and North Korea were already in effect. However general Matthew B. Ridgway was not satisfied with one member of the U.N. negotiation team, Major general Claude B. Ferenbaugh and replaced him with Harrison in January 1952.[1][6][4]

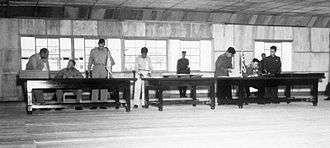

Harrison was attached to the U.S. team under Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy and participated in the regular negotiations with North Korean and Chinese representatives at Panmunjon. The negotiations were ineffective and communists used the truce talks just for propaganda purposes and to strengthen their positions on the Jamestown Line. Admiral Joy was planning his own departure in mid-1952 and recommended Harrison as his replacement.[4]

Ridgway agreed and announced the change of command to Washington, where it was confirmed in May 1952, when Harrison was appointed senior member of the Korean Armistice Delegation. He also nominated Harrison for the temporary rank of lieutenant general, but Armed Service Committee rejected the promotion.[1][6][2][4]

In May 1952, General Mark W. Clark, another Harrison's West Point classmate and friend, succeeded Ridgway as Commander-in-Chief, United Nations Command Korea and urged Harrison's promotion again. The Army Chief of Staff, General J. Lawton Collins, who was also a West Point classmate of Harrison, convinced the committee and Harrison was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general on September 8, 1952.[6][4][5]

General Clark later commented:

I know that Billy wanted a field command. He's an old cavalry man, and the cavalry's always looking for a charge. But I knew we needed someone with the strength of character to look the Communists in the eye and say, 'Bull!' Not that Billy Harrison would ever say it quite that way, but the Reds would get his message.[3]

Following the promotion, Harrison was appointed Chief of Staff and Deputy Commanding general, Far East Command under General Mark W. Clark and retained his assignment as Senior Member in the truce talks team. He participated in the regular meetings with North Korean delegation led by General Nam Il and had to handle more North Korean attempts to use truce talks as the platform for propaganda. He despised the communists, who he regarded with contempt as common criminals and for example in June 1952, he left the truce meeting, when he saw that the negotiation was without result, leaving North Korean General Nam Il flabbergasted.[3][4]

In September 1953, Harrison assumed duty as Chief of Staff and Deputy Commanding general, Far East Command under General Mark W. Clark and remained in that capacity under General John E. Hull, who replaced Clark in October 1953. Harrison served in the Far East until May 1954, when he returned to the United States for new assignment. For his service in Korea during the Armistice negotiations and later with Far East Forces, he was decorated with Navy Distinguished Service Medal. Queen Elizabeth awarded him the Companion of the Most Honorable Order of the Bath.[1][7][8][4]

Later service

Upon his return stateside, Harrison was welcomed as a hero, who brought peace in Korea. He attended many parades and banquets, where he featured as speaker and was given honorary degrees from the Wheaton College in Illinois and the Houghton College in New York. Harrison was also featured as speaker at Easter sunrise service at the famous Rose Bowl stadium in Pasadena, California.

He then arrived to the Panama Canal Zone on June 16, 1954 and assumed duty as Commander-in-Chief, United States Caribbean Command with headquarters in Quarry Heights. His main task was the defense of the Panama Canal and its coast, which was divided into Atlantic and Pacific Sectors. Harrison arrived in a country with an unstable political situation, because a few months after his arrival, President of Panama, José Antonio Remón Cantera was assassinated and his successor, José Ramón Guizado, was arrested for conspiracy and murder.

Harrison participated in many ceremonies including the Inauguration of President Ernesto de la Guardia in October 1956 (as a member of the United States delegation). He also hosted President Dwight D. Eisenhower and then-Vice President Richard Nixon in 1955.

He instituted military training exercises, both amphibious and paratroop, in the Canal Zone and forces came from the United States. Harrison intended to demonstrate to Panama's neighbors the capabilities of the United States Army. Harrison was succeeded by lieutenant general Robert M. Montague at the end of January 1957 and returned to the United States, awaiting retirement.[1][6][8][4]

Retirement

Harrison retired from the Army on February 28, 1957 after almost 40 years of service and settled in Chicago, where he served as Executive Director of the Evangelical Child Welfare Agency until 1960. General Harrison served as president of Officers' Christian Fellowship from 1954-1972 and as president emeritus from 1972 until his death. He was also a member of the Lownes Free Church and the Alumni Association of the United States Military Academy and as a trustee of The Stony Brook School in Stony Brook, New York.[2][9][8]

Lieutenant general William K. Harrison Jr. died on May 25, 1987 in Bryn Mawr Terrace, a nursing home in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, aged 91. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia.[10][3][5]

His first wife, the former Eva Toole, and his second wife, the former Forrest King, are deceased. He is survived by three sons, William K. III, W. Terry and Wayne King; a daughter, Evelyn H. Kent; 9 grandchildren; and 7 great-grandchildren. [10]

Decorations

Here is Lieutenant General Harrison's ribbon bar:[7][6]

| 1st Row | Distinguished Service Cross | Army Distinguished Service Medal | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Row | Navy Distinguished Service Medal | Silver Star | Legion of Merit | Bronze Star Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster | Fourragère | ||||||||||||

| 3rd Row | Purple Heart | World War I Victory Medal | American Defense Service Medal | American Campaign Medal | |||||||||||||

| 4th Row | European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with five 3/16 inch service stars | World War II Victory Medal | Army of Occupation Medal | National Defense Service Medal | |||||||||||||

| 5th Row | Korean Service Medal with three 3/16 inch service stars | Companion of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom) | Distinguished Service Order (United Kingdom) | Knight of the Legion of Honor (France) | |||||||||||||

| 6th Row | French Croix de guerre 1939-1945 with Palm | Dutch Order of Orange-Nassau, Officer | Soviet Order of the Red Banner | United Nations Korea Medal | |||||||||||||

Notes

- "Biography of Lieutenant-General William Kelly Harrison Jr. (1895 - 1987), USA". generals.dk. generals.dk Websites. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- "William Kelly Harrison Jr. - Arlington National Cemetery".

- "W.K. HARRISON, 91, ARMY GENERAL, DIES".

- Lockerbie, Bruce D. (1979). A man under orders: Lieutenant general William K. Harrison Jr. Harper&Row. pp. 192. ISBN 0-06-065257-8. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- "William K. Harrison Jr. Papers – Army Center of Military History". USMC Military History Division. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- "William K. Harrison Jr. 1917 - West Point Association of Graduates".

- "Valor awards for William K. Harrison Jr". valor.militarytimes.com. Militarytimes Websites. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- "Lt. General William K. Harrison Jr. – Musings of a Snickerdoodle".

- "Professional Excellence for the Christian Officer" (PDF). ocfusa.org. Officers' Christian Fellowship Websites. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- "LTG William K. Harrison Jr. (1895 – 1987) – Find A Grave Memorial".

Further reading

A Man Under Orders: Lieutenant General William K. Harrison, Jr.. LOCKERBIE, D BRUCE. Harper & Row, 1979. ISBN 0-06-065257-8.

External links

- Arlington National Cemetery record

- Dallas Theological Seminary archive

- "Professional Excellence for the Christian Officer"

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Horace L. McBride |

Commander-in-Chief, United States Caribbean Command June 1954 – January 1957 |

Succeeded by Robert M. Montague |

| Preceded by John M. Devine |

Commanding General, 9th Infantry Division September 1950 – February 1952 |

Succeeded by Roderick R. Allen |

| Preceded by Walter M. Robertson |

Commanding General, 2nd Infantry Division June 1945 – September 1945 |

Succeeded by Edward M. Almond |