Malmedy massacre

The Malmedy massacre was a war crime committed by members of Kampfgruppe Peiper (part of the SS Division Leibstandarte), a German Waffen-SS unit led by Joachim Peiper, at Baugnez crossroads near Malmedy, Belgium, on 17 December 1944, during the Battle of the Bulge. Eighty-four American prisoners of war were massacred by their German captors. The prisoners were assembled in a field and shot with machine guns; those still alive were killed by close-range shots to the head.

| Malmedy Massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Bulge and World War II | |

Murdered American soldiers at Malmedy (picture taken on 14 January 1945) | |

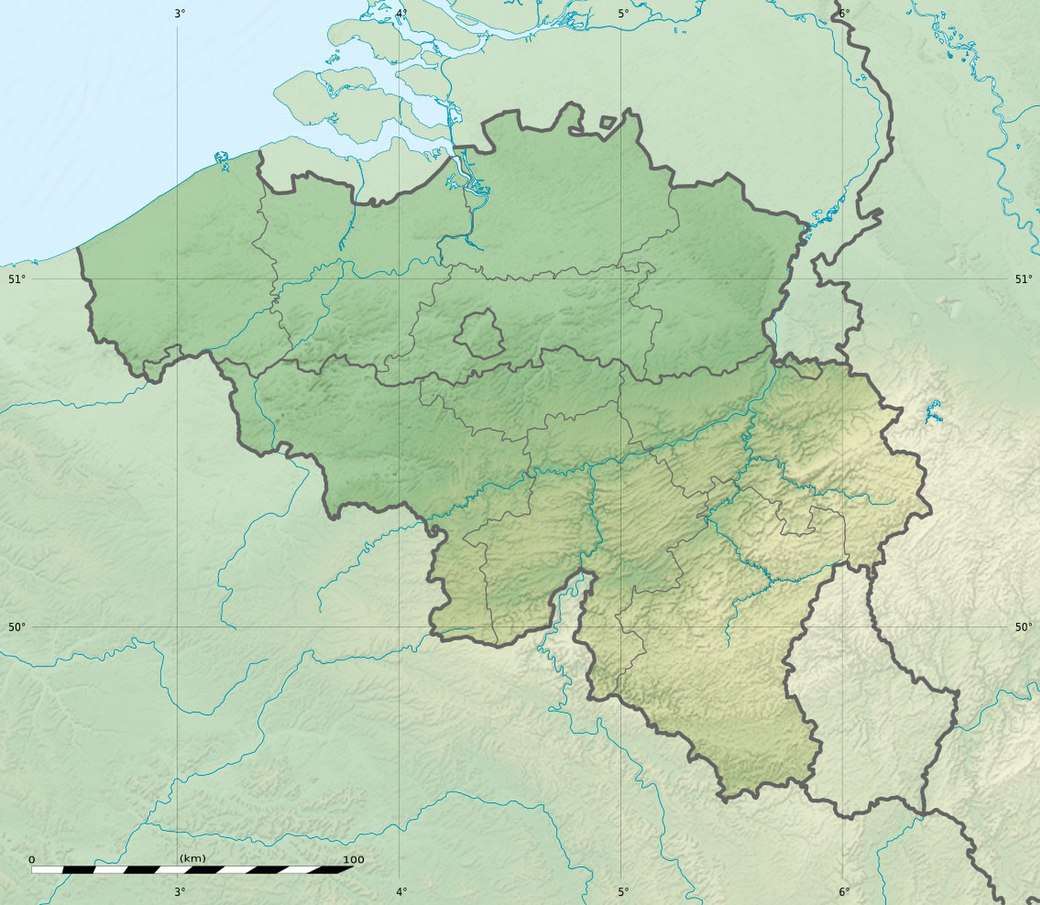

Malmedy massacre (Belgium) | |

| Location | Malmedy, Belgium |

| Coordinates | 50°24′14″N 6°3′58.30″E |

| Date | 17 December 1944 |

Attack type | Mass murder by machine gun and shots to the head |

| Deaths | 84 American POWs of the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion and other units |

| Perpetrators |

|

The term Malmedy massacre also applies generally to the series of massacres committed by the same unit on the same day and following days, which were the subject of the Malmedy massacre trial, part of the Dachau Trials of 1946.

Background

Hitler's main objective for the Battle of the Bulge was for the 6th SS Panzer Army commanded by SS General Sepp Dietrich to break through the Allied front between Monschau and Losheimergraben, cross the Meuse River, and capture Antwerp.[1][2]:5 Kampfgruppe Peiper, named after and under the command of SS-Obersturmbannführer Joachim Peiper, was composed of armoured and motorised elements and was the spearhead of the left wing of the 6th SS Panzer Army. Once the infantry had breached the American lines, Peiper's role was to advance via Ligneuville, Stavelot, Trois-Ponts, and Werbomont and seize and secure the Meuse bridges around Huy.[1]:260+[2][3] The best roads were reserved for the bulk of the SS Division Leibstandarte. Peiper was to use secondary roads, but these proved unsuitable for heavy armoured vehicles, especially the Tiger II tanks attached to the Kampfgruppe.[1][2][3] The success of the operation depended on the swift capture of the bridges over the Meuse. This required a rapid advance through US positions, circumventing any points of resistance whenever possible. Another factor Peiper had to consider was the shortage of fuel.

Hitler ordered the battle to be carried out with a brutality more common on the Eastern Front, in order to frighten the enemy.[2] Sepp Dietrich confirmed this during the war crimes trial after the war ended.[4] According to one source, during the briefings before the operation, Peiper stated that no quarter was to be granted, no prisoners taken, and no pity shown towards Belgian civilians.[4]

Peiper advances west

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Germans' initial position was east of the German-Belgium border and the Siegfried Line near Losheim. SS General Sepp Dietrich's plan was for the 6th SS Panzer Army to advance northwest through Losheimergraben and Bucholz Station and then drive 72 miles (116 km) through Honsfeld, Büllingen, and a group of villages named Trois-Ponts, to connect to Belgian Route Nationale N23, and cross the River Meuse.[5]:70

Peiper had planned to use the Lanzerath-Losheimergraben road to advance on Losheimergraben immediately following the infantry, who were tasked with capturing the villages and towns immediately west of the International Highway. Unfortunately for the Germans, during their retreat earlier in the year they had destroyed the Losheim-Losheimergraben road-bridge over the railway, which prevented their use of this route. A rail overpass they had planned to use could not bear the weight of the German armour, and German engineers were slow to repair the Losheim-Losheimergraben road, forcing Peiper's vehicles to take the road through Lanzerath to Bucholz Station.[6]:34 Peiper's forces were delayed by massive traffic jams behind the front.[1][2]

But German operations on the northern front, the key route for the entire Battle of the Bulge, were troubled by unexpectedly obstinate resistance from American troops. A single platoon of 18 men belonging to an American reconnaissance platoon and four US Forward Artillery Observers held up a battalion of about 500 German paratroopers in the village of Lanzerath, Belgium for almost an entire day.[6]:34 Peiper's entire timetable for his advance towards the River Meuse and Antwerp was seriously slowed, allowing the Americans precious hours to move in reinforcements.[5]

The German 9th Parachute Regiment, 3rd Parachute Division finally flanked and captured the American platoon at dusk, when they ran low on ammunition and were planning to withdraw. Only one American, a forward artillery observer, was killed, while 14 were wounded: German casualties totalled 92. The Germans paused, believing the woods were filled with more Americans and tanks. Only when Peiper and his tanks arrived at midnight, twelve hours behind schedule, did the Germans learn the woods were empty.[5]

First massacre at Büllingen

At 04:30 on 17 December, more than 16 hours behind schedule, the 1st SS Panzer Division rolled out of Lanzerath and headed east for Honsfeld.[7] After capturing Honsfeld, Peiper left his assigned route for several kilometres to seize a small fuel depot in Büllingen, where members of his force killed several dozen American POWs.[1][2][8]

Unknown to Peiper, he was in a position to flank the 2nd and the 99th Infantry Divisions: had his troops advanced north from Büllingen towards Elsenborn, they may have been able to flank and trap the American units. But Peiper followed orders. He was more determined to advance west and he stuck to his Rollbahn towards the Meuse River and captured Ligneuville, bypassing Mödersheid, Schoppen, Ondenval, and Thirimont.[9]

The terrain and poor quality of the roads made his advance difficult. Eventually, at the exit of the small village of Thirimont, the spearhead was unable to take the direct road toward Ligneuville. Peiper again deviated from his planned route. Rather than turn left, the spearhead veered right and advanced towards the crossroads of Baugnez, which is equidistant from Malmedy, Ligneuville, and Waimes.[1][2]

Massacre at Baugnez crossroads

Between noon and 1 pm, the German spearhead approached the Baugnez crossroads, two miles south-east of Malmedy. An American convoy of about thirty vehicles, mainly elements of B Battery of the American 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion, was negotiating the crossroads and turning right toward Ligneuville and St. Vith, where it had been ordered to join the 7th Armored Division.[2][7] The spearhead of Peiper's group spotted the American convoy and opened fire, immobilising the first and last vehicles of the column and forcing it to halt.[7] Armed with only rifles and other small arms, the Americans surrendered to the German tank force.[1][2]

The armoured column led by Peiper continued west toward Ligneuville. The German troops left behind assembled the American prisoners in a field along with other prisoners captured earlier in the day. Many of the survivors testified that about 120 troops were standing in the field when, for unknown reasons, the SS troops suddenly opened fire with machine guns on the prisoners.[1][2]

As soon as the SS machine gunners opened fire, the POWs panicked. Some tried to flee, but most were shot where they stood. Some dropped to the ground and pretended to be dead.[2] SS troops walked among the bodies and shot any who appeared to be alive.[2][7] A few sought shelter in a café at the crossroads. The SS soldiers set fire to the building and shot any who tried to escape.[2]

Massacre revealed

A few survivors emerged from hiding shortly afterwards and returned through the lines to nearby Malmedy, where American troops still held the town. Eventually, 43 survivors emerged, some who had taken shelter with Belgian civilians.[10] The first survivors of the massacre were found by a patrol from the 291st Combat Engineer Battalion at about 2:30 p.m. the same day. The survivors were interviewed soon after they returned to American lines. Their stories were consistent and corroborated each other, although they had not had a chance to discuss the events with each other.[7] The inspector general of the First Army learned of the shootings about three or four hours later. By late evening of the 17th, rumours that the enemy was killing prisoners had reached the forward American divisions.[1]

Private Harold Billow, 97 years old in 2020, is believed to be the last survivor.[11][12]

One US unit issued orders that "No SS troops or paratroopers will be taken prisoner but will be shot on sight."[1]:261–264 Some American forces may have killed German prisoners in retaliation, like the shooting of German prisoners that took place at Chenogne on January 1, 1945.[1]:261–264

Bodies recovered

The Baugnez crossroads was behind German lines until the Allied counter-offensive in January. On 14 January 1945, US forces reached the crossroads and massacre site. They photographed the frozen, snow-covered bodies where they lay, and then removed them from the scene for identification and detailed post mortem examinations. The investigation was focused on documenting evidence that could be used to prosecute those responsible for the apparent war crime.[13] Seventy-two bodies were found in the field on 14 and 15 January 1945. Twelve more, lying farther from the pasture, were found between 7 February and 15 April 1945.

About 20 of the 84 bodies recovered had powder burn residue on their heads, indicating a deliberate shot to the head at point-blank range consistent with a massacre and not self-defence nor injuries received while attempting to escape.[13] The bodies of another 20 showed evidence of small-caliber gunshot wounds to the head but didn't display powder-burn residue.[13] Some bodies showed only one wound, in the temple or behind the ear.[14] Ten other bodies showed fatal crushing or blunt-trauma injuries, most likely from rifle butts.[13] The head wounds were in addition to bullet wounds made by automatic weapons. Most of the bodies were found in a very small area, suggesting the victims were gathered close together before they were killed.[10]

The opening forced through the American lines by Kampfgruppe Peiper was marked by other murders of prisoners of war, and later of Belgian civilians. Members of his unit killed at least eight other American prisoners in Ligneuville.[15]

Further massacres of POWs were reported in Stavelot, Cheneux, La Gleize, and Stoumont, on 18, 19 and 20 December.[8] Finally, on 19 December 1944, between Stavelot and Trois-Ponts, German forces tried to regain control of the bridge over the Amblève River in Stavelot, which was crucial for receiving reinforcements, fuel, and ammunition. Peiper's men killed about 100 Belgian civilians.[2][8][16][17]

American Army engineers blocked Peiper's advance in the narrow Amblève River valley by blowing up the bridges. Additional US reinforcements surrounded the Kampfgruppe in Stoumont and la Gleize.[2] Peiper and 800 of his men eventually escaped this encirclement by marching through the nearby woods and abandoning their heavy equipment, including several Tiger II tanks.[1][2]:376ff

On 21 December, during the battle around La Gleize, Peiper's battle group captured an American officer, Major Harold D. McCown, who was leading one of the battalions of the 119th US Infantry Regiment.[1]:365ff Having heard about the Malmedy massacre, McCown personally asked Peiper about his fate and that of his men. McCown testified that Peiper told him neither he nor his men were at any risk and that he (Peiper) was not accustomed to killing his prisoners.[2] McCown noted that neither he nor his men were threatened in any manner, and he testified in Peiper's defence during the 1946 trial in Dachau. As was pointed out at trial however, by the time Col. McCown (having been promoted since) was captured near La Gleize on 21 December, Peiper's tactical situation had deteriorated and he knew that he and his men were likely to be taken prisoner themselves. On 17 December at Malmedy, Peiper's unit was still advancing aggressively and had hope of reaching its objective, whereas by 21 December at La Gleize, he was nearly cut-off, out of fuel, and had sustained over 80% casualties. Peiper kept Col. McCown and others essentially as bargaining chips as his unit fled La Gleize on foot, only for Col. McCown to escape in the confusion.[18]

Once re-equipped, Kampfgruppe Peiper rejoined the battle, and other killings of POWs were reported on 31 December 1944, in Lutrebois, and between 10 and 13 January 1945, in Petit Thier, where killings were personally ordered by Peiper.[8] The precise number of prisoners of war and civilians massacred attributable to Kampfgruppe Peiper is still not clear. According to certain sources, 538 to 749 POWs had been the victims of war crimes perpetrated by Peiper's men. These figures are not corroborated by the report of the United States Senate subcommittee that later inquired into the subsequent trial; according to the Committee.[19] According to this report, the count of POWs or civilians killed at different places is as follows:

| Place | Prisoners of war killed | Civilians killed |

|---|---|---|

| Honsfeld | 19 | |

| Büllingen | 59 | 1 |

| Baugnez | 86 | |

| Ligneuville | 58 | |

| Stavelot | 8 | 93 |

| Cheneux | 31 | |

| La Gleize | 45 | |

| Stoumont | 44 | 1 |

| Wanne | 5 | |

| Trois-Ponts | 11 | 10 |

| Lutrebois | 1 | |

| Petit Thier | 1 | |

| Wereth | 11 | |

| Total | 373 | 111 |

Aftermath and trial

On 13 January 1945, American forces recaptured the site where the killings had occurred. The cold had preserved the scene well. The bodies were recovered on 14/15 January 1945. The memorial at Baugnez bears the names of the murdered soldiers.

In addition to the effect the event had on American combatants in Europe, news of the massacre greatly affected the United States. This explains why the alleged culprits were deferred to the Dachau Trials, which were held in May and June 1946, after the war.[20]

In what came to be called the "Malmedy massacre trial", which concerned all of the war crimes attributed to Kampfgruppe Peiper during the Battle of the Bulge, the highest-ranking defendant was General Sepp Dietrich, commander of the 6th SS Panzer Army, to which Peiper's unit had belonged. Joachim Peiper and his principal subordinates were defendants.[20] The tribunal tried more than 70 persons and pronounced 43 death sentences (none of which were carried out) and 22 life sentences. Eight other men were sentenced to shorter prison sentences.[20]

After the verdict, the way in which the court had functioned was disputed, first in Germany (by former Nazi officials who had regained some power due to anti-Communist positions with the occupation forces), then later in the United States (by Congressmen from heavily German-American areas of the Midwest). The case was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States, which made no decision. The case then came under the scrutiny of a sub-committee of the United States Senate.[19]

This drew attention to the trial and the judicial irregularities that had occurred during the interrogations that preceded the trial. But, before the United States Senate took an interest in this case, most of the death sentences had been commuted, because of a revision of the trial carried out by the US Army.[20] The other life sentences were commuted within the next few years. All the convicted war criminals were released during the 1950s, the last one to leave prison being Peiper in December 1956.

A distinct case about the war crimes committed against civilians in Stavelot was tried on 6 July 1948, in front of a Belgian military court in Liege, Belgium. The defendants were 10 members of Kampfgruppe Peiper; American troops had captured them on 22 December 1944, near the spot where one of the massacres of civilians in Stavelot had occurred. One man was discharged; the others were found guilty. Most of the convicts were sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment; two officers were sentenced to 12 and 15 years.

Towards the end of his life, Peiper settled in Traves. In 1976 a Communist historian found the Peiper file in the Gestapo archives held by East Germany. On 21 June, flyers denouncing Peiper's presence were distributed in the village. A day later, an article in the left-wing L'Humanité revealed Peiper's presence in Traves, and he received death threats. During the early morning hours of 14 July, Peiper's house was set on fire. Peiper had died from smoke inhalation. The perpetrators were never identified.[21]

See also

- List of massacres in Belgium

- Wereth Massacre, the torture and killing of 11 African-American prisoners of war in Wereth, committed by the 1st SS Panzer Division on the same day.

- Chenogne massacre

Notes

^ i: In Cole's history of World War II, footnote 5 on page 264 reads, Thus Fragmentary Order 27. issued by Headquarters, 328th Infantry, on December 21 for the attack scheduled the following day says: "No SS troops or paratroopers will be taken prisoner but will be shot on sight."[1]

^ ii: That article includes a diagram showing where the bodies were discovered.[10]

References

- Cole, Hugh M. (1965). "Chapter V: The Sixth Panzer Army Attack". The Ardennes. United States Army in World War II, The European Theater of Operations. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History.

- MacDonald, Charles (1984). A Time For Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-34226-6.

- Émile Engels, ed. (1994). Ardennes 1944–1945, Guide du champ de bataille (in French). Racine, Bruxelles.

- Gallagher, Richard (1964). Malmedy Massacre. Paperback Library. pp. 110–111.

- Kershaw, Alex (30 October 2005). The Longest Winter: The Battle of the Bulge And the Epic Story of World War II's Most Decorated Platoon. Da Capo Press. p. 330. ISBN 0-306-81440-4.

- Cavanagh, William (2005). The Battle East of Elsenborn. City: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 1-84415-126-3.

- Reynolds, Michael (February 2003). Massacre At Malmédy during the Battle of the Bulge. World War II Magazine. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007.

- Review and Recommendation of the Deputy Judge Advocate for War Crimes. 20 October 1947. pp. 4–22.

- Cole (1965). Statement of General Lauer "the enemy had the key to success within his hands, but did not know it."

- Glass, Lt Col Scott T. (22 November 1998). "Mortuary Affairs Operations at Malmedy". Centre de Recherches et d'Informations sur la bataille des Ardennes. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- Cornelius, Cornelius (10 November 2019). "Every Veterans Day, Malmedy Massacre survivor Harold Billow remembers his fallen comrades". Lancaster OnLine. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Kinney, Brendan (6 January 2020). "Mount Joy WWII veteran honored with letter from President Trump". WHP. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- Glass, MAJ Scott T. "Mortuary Affairs Operations At Malmedy—Lessons Learned From A Historic Tragedy".

- Roger Martin, L'Affaire Peiper, Dagorno, 1994, p. 76

- Toland, John (December 1959). The Brave Innkeeper of 'The Bulge'. Coronet Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007.

- Kent, Capt John E. "Stavelot, Belgium, 17 to 22 December 44". Centre de Recherches et d'Informations sur la Bataille des Ardennes. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007.

- Lebeau, Guy. "Sad souvenirs or life of the people of Stavelot during the winter of 1944–1945". Centre de Recherches et d'Informations sur la Bataille des Ardennes. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Goldstein, Donald M.; Dillon, Katherine V.; Wenger, J. Michael (1994). Nuts!: The Battle of the Bulge: The Story and Photographs. London: Brassey's. pp. 167–182.

- Malmedy massacre Investigation–Report of the Subcommittee of Committee on Armed Services. United States Senate Eighty-first Congress, first session, pursuant to S. res. 42, Investigation of action of Army with Respect to Trial of Persons Responsible for the Massacre of American Soldiers, Battle of the Bulge, near Malmedy, Belgium, December 1944. 13 October 1949.

- Parker, Danny S. (13 August 2013). "Fatal Crossroads: The Untold Story of the Malmedy Massacre at the Battle of Bulge" (paperback ed.). Da Capo Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-0306821523.

- Westemeier, Jens (2007). Joachim Peiper: A Biography of Himmler's SS Commander. Schiffer Publications. ISBN 978-0-7643-2659-2.

Further reading

- Steven P. Remy, The Malmedy Massacre: The War Crimes Trial Controversy (Harvard University Press, 2017), x, 342 pp.

External links

- Mortuary Affairs Operations At Malmedy – Lessons Learned From A Historic Tragedy, by Major Scott T. Glass. Quartermaster Professional Bulletin, Autumn 1997

- Battle of the Bulge on the Web, Malmedy Massacre resources

- "Massacre at Malmédy during the Battle of the Bulge" (reprint of an article in World War II [2003] by M. Reynolds)

- Gettysburg Daily article on 65th anniversary of the Malmedy Massacre.

- Fatal Crossroads: The Untold Story of the Malmédy massacre at the Battle of the Bulge, Book by Danny S. Parker, November 2011

.jpg)