Wildlife of Turkmenistan

The wildlife of Turkmenistan is the flora and fauna of Turkmenistan, and the natural habitats in which they live. Turkmenistan is a country in Central Asia to the east of the Caspian Sea. Two thirds of the country is hot dry plains and desert, and the rest is more mountainous. Very little rain falls in summer and the chief precipitation occurs in the southern part of the country in the winter and spring. The Caspian coast has milder winters.

The desert sees limited plant growth in the winter, with grasses and xeric plants and shrubs sprouting, and with the arrival of spring, the rains encourage the growth and flowering of ephemeral plants. The mountains in the south of the country are covered in shrublike and juniper woodlands, and larger trees grow in the gullies and river valleys.

A wide range of animals are found in Turkmenistan, including 91 species of mammal, 82 species of reptile and nearly 400 species of bird. A number of nature reserves and sanctuaries have been created for the preservation of the natural landscapes and the conservation of the wildlife.

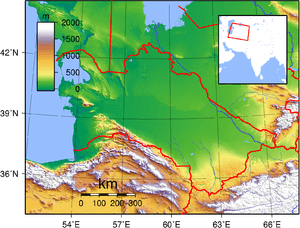

Geography

Turkmenistan has an area of nearly 500,000 km2 (193,100 sq mi). Iran and Afghanistan lie to the south, Uzbekistan lies to the north-east and Kazakhstan to the north-west, and it has a long coastline on the Caspian Sea to the west. Most of the surface is flat, rolling, sandy terrain forming the Karakum Desert. To the southwest of the country, on the border with Iran, lies the Kopet Dag Range of mountains. This region is characterized by foothills, dry and sandy slopes, mountain plateaus and steep ravines; here the highest point is Mount Şahşah 2,912 m (9,554 ft). The land also rises in the southeastern corner of the country towards the mountain ranges of Afghanistan. At the extreme east of Turkmenistan is the Köýtendag Range with the highest mountain in the country, Mount Aýrybaba (3,138 m (10,295 ft)).[1]

The Murghab River and the Tejen River flow from Afghanistan but peter out in the Karakum Desert. The Atrek River is a shorter river flowing from Iran, but only reaching the Caspian Sea in time of flood. The Amudarya River flows northwestwards near the border with Uzbekistan before emptying into the remnants of the Aral Sea. Garabogazköl gulf is a large shallow lagoon that is sometimes connected to the Caspian Sea and has a much higher salinity,[1] surpassing the far-famed hypersaline lake of the Dead Sea.[2]

With the exception of the Caspian coast, the climate of Turkmenistan is continental, with hot dry summers with the average July temperatures exceeding 30 °C (86 °F). In the Karakum Desert, summer temperatures can reach 50 °C (122 °F), while on the coast they are a little less hot, but it is more humid.[3] In the winter, the north is cold and moist, with a mean January temperature of −10 to 0 °C (14 to 32 °F), while the south is slightly less cold and also moist, with the temperature averaging above 0 °C (32 °F). The daily temperature range is large. The highest precipitation is in the mountains, mostly falling in the winter and spring, while elsewhere the precipitation is low, and over most of the country, water is in short supply.[4]

Ecoregions

Ecoregions in Turkmenistan include the Central Asian southern desert covering much of the central and northern part of the country, and the Kopet Dag woodlands and forest steppe in the southwestern portion.[5] This hilly and mountainous ecoregion has a mixed character, showing the influence of the Mediterranean and Turanian biogeographical regions.[6]

Flora

Over 2,000 species of vascular plant have been recorded in Turkmenistan including 462 relic and endemic species. The greatest diversity is in the mountains of the south, with many economically important fruit-bearing trees being found there, including persimmon, almond, cherry, pomegranate and fig.[7]

The Kopet Dag woodlands consists of xeric, shrublike woodlands known as "shiblyak", juniper woodlands, and riparian forest. Shiblyak woodland is dominated by Turkmen maple (Acer tucomanicum), hawthorns (Crataegus spp.) and the Jerusalem thorn (Paliurus spinachristi). At higher altitudes, there are fewer maples and the dominant trees are hawthorn, Juniperus turcomanica and Celtis caucasica. On the mountain tops, grasses and cushion plants are the main members of the plant community. In the steep sided ravines, there are walnut trees, Syrian ash, Thelycrania meyeri, Prunus divaricata, Lonicera floribunda, Rubus sanguinoides and Rosa lacerans.[8]

Much of the rest of the country makes up the Central Asian Southern Desert ecoregion, which includes the Karakum Desert, the southern part of the Kyzylkum Desert and other areas with rolling dunes, sandy plateaus and alluvial plains. This area receives practically no rain during the summer and the extreme heat means that little grows at this time of year. In the winter, some precipitation with much cooler temperatures occurs, and grasses such as Bromus and vascular plants such as Malcolmia, Koelpinia and Amberboa sprout. In March and April, ephemeral plants appear, including fox-tail lilies, Rheums, tulips and stars of Bethlehem, but by the end of May these have given way to the summer drought. Communities of Salsola grow on the alluvial flats along with asafoetida, Ephedra strobilacea, black saxaul and white saxaul. The sand acacia and several species of Calligonum grow among the dunes.[9]

The coastal strip consists of sandy and clayey salt deserts recently exposed by the retreating shoreline. It has unconsolidated dunes and is sparsely vegetated with salt-loving plants.[10] This area, with its milder climate and the mists that sometimes roll in from the Caspian Sea, is home to many of the 90 species of lichen found in the country. Another lichen-rich environment is the takirs that form as flaking crusts on drying clayey plains.[11]

Fauna

Turkmenistan has a range of habitats and these support a wide range of animal life. There are 91 species of mammal recorded in the country, some of which are threatened.[12] There are bats in the caves, leopards, bears, mountain sheep, wild ass and goitered gazelles in the mountains, and seals in the Caspian Sea. In the deserts are long-eared hedgehog, Brandt's hedgehog and tolai hare, as well as gerbils, jerboas and other rodents.[13]

The endangered mammals include the Blasius's horseshoe bat, two subspecies of the Eurasian brown bear, the Eurasian lynx, the Asian subspecies of cheetah (extinct) , the leopard, the striped hyena, the Pallas's cat, the sand cat, the caracal, the Caspian seal, the red deer, the Turkmen wild goat, the markhor and the Turkmen mountain sheep.[14] The great Balkan mouse-like hamster is one of a number of mammals endemic to this region.[15] Another is the Turkmen ratel, a subspecies of the honey badger.[16]

Reptiles are plentiful, with 82 species having been recorded.[7] Some of the most notable include the desert monitor, the European pond turtle, the Caspian turtle, the Russian tortoise, the dice snake, and the Transcaspian saw-scaled viper.[7] There are also skinks, geckoes, agamas, wall lizards, the European legless lizard, vipers, rat snakes and the blind wormsnake.[6] The Turkmen eyelid gecko is another native species.[17] Amphibians are much more scarce, with 5 species recorded including the European green toad and the marsh frog.[7] As well as freshwater fish in the streams, rivers and lakes, the Caspian Sea is home to 124 species of mostly endemic fish.[7]

Nearly four hundred species of bird have been recorded in the country. Many of them are resident species but others are migratory and just passing through, while still others overwinter in Turkmenistan. Some of these are the ducks, geese, and swans that inhabit the shores of the Caspian at this time of year.[7] The largest lake in the country is Sarygamysh Lake, on the border with Uzbekistan; this is now a nature reserve and attracts wildfowl including pelicans, coots and cormorants. Yeroylanduz is a 300 square kilometres (120 sq mi) natural depression which floods each year and attracts pelicans, flamingoes and other birds.[12]

Birds that are commonly seen in Turkmenistan include the crested lark, the chukar partridge, the common pheasant, the rock dove, the European turtle dove and the Oriental turtle dove. Birds of prey include the Eurasian sparrowhawk, the shikra, the long-legged buzzard, the black kite and the common kestrel. Passerine birds frequently encountered include titmice, flycatchers, nightingales, finches, buntings, warblers and shrikes.[6]

Conservation

There are 29 species of endangered or critically endangered mammal, 40 species of bird, 20 species of reptile and 14 species of fish listed in the 2011 edition of the Red Data Book of Turkmenistan.[14] The mountainous area of Kopet Dag is under threat from overgrazing by cattle with much of the forest having been cleared for firewood. Soil erosion creates mud flows when heavy rains occur, damaging woodland lower down the slopes and riverside habitats. Conversely, particularly dry summers have created conditions where wild fires are frequent, and this puts at risk the unique communities of fruiting trees and the rare mammals.[8]

There are a number of nature reserves in the country. Badhyz State Nature Reserve is a sanctuary for the Turkmen kulan, and Repetek Biosphere State Reserve preserves the desert flora and fauna.[12] Another desert reserve, the Bereketli Garagum Nature Reserve, was established in 2013 and is "designed to preserve the unique ecological system and natural resources of the Karakum Desert".[18] Köýtendag Nature Reserve, Köpetdag Nature Reserve and Gaplaňgyr Nature Reserve are all mountain reserves in different parts of the country.[12] Although these reserves contribute to the conservation of the wildlife, they sometimes lack effective management, and poaching and habitat destruction are still occurring.[8]

References

- Philip's (1994). Atlas of the World. Reed International. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-540-05831-0.

- "Garabogazköl". Dark Tourism. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- "Climate: Turkmenistan". Climates to Travel. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- Zonn, Igor S.; Kostianoy, Andrey G. (2013). The Turkmen Lake Altyn Asyr and Water Resources in Turkmenistan. Springer. p. 42. ISBN 978-3-642-38607-7.

- "Turkmenistan". Living National Treasures. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- "Central Asia: Southern Turkmenistan and northern Iran". Montane grasslands and shrublands. WWF. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- "Biological Diversity". State of the Environment: Turkmenistan. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- World Wildlife Fund (16 May 2014). "Kopet Dag woodlands and forest steppe". The Encyclopedia of Earth. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- World Wildlife Fund (16 May 2014). "Central Asian southern desert". The Encyclopedia of Earth. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- Fet, Victor; Atamuradov, Khabibulla I. (1994). Biogeography and Ecology of Turkmenistan. Monographiae Biologicae. 72. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-1116-4. ISBN 978-94-010-4487-5.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Abdurahimova, Zuvaydajan (2010). "Lichens Flora of Deserts of Turkmenistan". Botany 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- "Turkmenistan flora and fauna". BTCIC. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- "Central Asia: Central Turkmenistan stretching into Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan". Deserts and xeric shrublands. WWF. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- Annabayramov, B., ed. (2011). "Volume 2: Invertebrate and Vertebrate Animals" (PDF). The Red Book of Turkmenistan (third edition). Ministry of Nature Protection of Turkmenistan. Retrieved 30 July 2017.

- Fet, Victor; Atamuradov, Khabibulla (2012). Biogeography and Ecology of Turkmenistan. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 206–212. ISBN 978-94-011-1116-4.

- Baryshnikov, G. (2000). "A new subspecies of the honey badger Mellivora capensis from Central Asia". Acta Theriologica. 45 (1): 45–55. doi:10.4098/at.arch.00-5.

- Natalia Ananjeva; Nikolai Orlov; Theodore Papenfuss; Soheila Shafiei Bafti (2009). "Eublepharis turcmenicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009: e.T164581A5910155. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009.RLTS.T164581A5910155.en.

- "New nature reserve established in Karakum desert". Turkmenistan.RU. 19 July 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2017.