Mirkwood

Mirkwood is a name used for a great dark fictional forest in novels by Sir Walter Scott and William Morris in the 19th century, and by J. R. R. Tolkien in the 20th century. The critic Tom Shippey explains that the name evoked the excitement of the wildness of Europe's ancient North.[1]

At least two distinct Middle-earth forests are named Mirkwood in Tolkien's legendarium. One is in the First Age, when the highlands of Dorthonion north of Beleriand became known as Mirkwood after falling under Morgoth's control. The more famous Mirkwood was in Wilderland, east of the river Anduin. It had acquired the name Mirkwood after it fell under the influence of the Necromancer; before that it had been known as Greenwood the Great. This Mirkwood features significantly in The Hobbit and in the film The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug.

The term Mirkwood was used by Sir Walter Scott in his 1814 novel Waverley, and then by William Morris in his 1889 fantasy novel The House of the Wolfings, influenced by the forest Myrkviðr of Norse mythology. Forests play a major role in the invented history of Tolkien's Middle-earth and are important in the heroic quests of his characters.[2] The forest device is used as a mysterious transition from one part of the story to another.[3]

In Sir Walter Scott's Waverley

The name Mirkwood was used by Sir Walter Scott in his 1814 novel Waverley, which had

a rude and contracted path through the cliffy and woody pass called Mirkwood Dingle, and opened suddenly upon a deep, dark, and small lake, named, from the same cause, Mirkwood-Mere. There stood, in former times, a solitary tower upon a rock almost surrounded by the water...[4][T 1]

In William Morris's fantasies

William Morris used Mirkwood in his fantasy novels. His 1889 The Roots of the Mountains is set in such a forest,[5] while the forest setting in his The House of the Wolfings, also first published in 1889, is actually named Mirkwood. The book begins by describing the wood:

The tale tells that in times long past there was a dwelling of men beside a great wood. Before it lay a plain, not very great, but which was, as it were, an isle in the sea of woodland, since even when you stood on the flat ground, you could see trees everywhere in the offing, though as for hills, you could scarce say that there were any; only swellings-up of the earth here and there, like the upheavings of the water that one sees at whiles going on amidst the eddies of a swift but deep stream.

On either side, to right and left the tree-girdle reached out toward the blue distance, thick close and unsundered...

In such wise that Folk had made an island amidst of the Mirkwood, and established a home there, and upheld it with manifold toil too long to tell of. And from the beginning this clearing in the wood they called the Mid-mark...[T 2]

In Tolkien's writings

A Mirkwood appears in several places in J. R. R. Tolkien's writings, among several forests that play important roles in his storytelling.[2] Projected into Old English, it appears as Myrcwudu in his The Lost Road, as a poem sung by Ælfwine.[T 3] He used the name Mirkwood in another unfinished work, The Fall of Arthur.[T 4] But the name is best known and most prominent in his Middle-earth legendarium, where it appears as two distinct forests, one in the First Age in Beleriand, as described in The Silmarillion, the other in the Third Age in Rhovanion, as described in both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings.[5]

The First Age forest in Beleriand

In The Silmarillion, the forested highlands of Dorthonion in the north of Beleriand (in the northwest of Middle-earth) eventually fell under Morgoth's control and was subjugated by creatures of Sauron, then Lord of Werewolves. Accordingly, the forest was renamed Taur-nu-Fuin in Sindarin, "Forest of Darkness", or "Forest of Nightshade";[T 5] Tolkien chose to use the English form "Mirkwood". Beren becomes the sole survivor of the men who once lived there as subjects of the Noldor King Finrod of Nargothrond. Beren ultimately escapes the terrible forest that even the Orcs fear to spend time in.[T 6] Beleg pursues the captors of Túrin through this forest in the several accounts of Túrin's tale. Along with the rest of Beleriand, this forest was lost in the cataclysm of the War of Wrath at the end of the First Age.[T 7]

The forest in Rhovanion

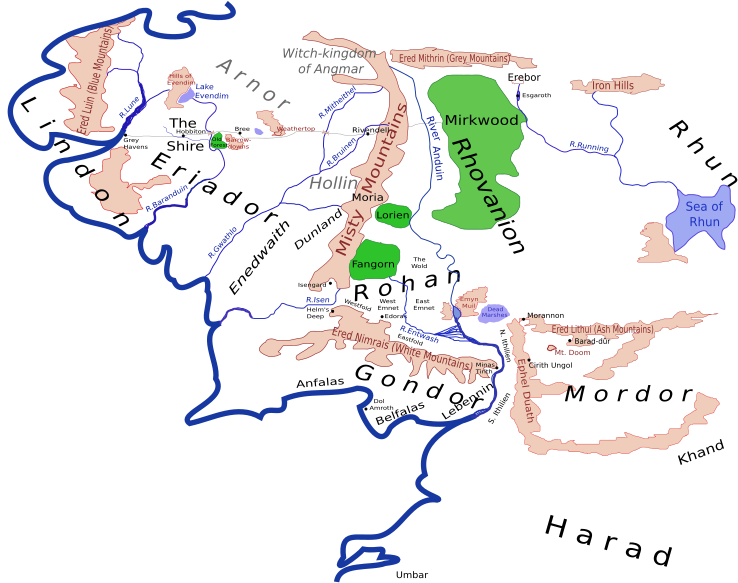

Mirkwood is a vast temperate broadleaf and mixed forest in the Middle-earth region of Rhovanion (Wilderland), east of the great river Anduin. In The Hobbit, the wizard Gandalf calls it "the greatest forest of the Northern world."[T 8] Before it was darkened by evil, it had been called Greenwood the Great.[T 9]

After the publication of the maps in The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien wrote a correction stating "Mirkwood is too small on map it must be 300 miles across" from east to west,[6] but the maps were never altered to reflect this. On the published maps Mirkwood was up to 200 miles (320 km) across; from north to south it stretched about 420 miles (675 km).[T 10] The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia states that it is 400-500 miles (640-800 km) long and 200 miles (320 km) wide.[5]

The trees were large and densely packed. In the north they were mainly oaks, although beeches predominated in the areas favoured by Elves.[5] Higher elevations in southern Mirkwood were "clad in a forest of dark fir".[T 11][5] Pockets of the forest were dominated by dangerous giant spiders.[T 12]Animals within the forest were described as inedible.[T 13] The elves of the forest, too, are "black" and hostile, drawing a comparison with Svartalfheim ("Black elf home") in Snorri Sturluson's Old Norse Edda, quite unlike the friendly elves of Rivendell.[7]

Near the end of the Third Age – the period in which The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings are set – the expansive forest of "Greenwood the Great" was renamed "Mirkwood", supposedly a translation of an unknown Westron name.[8] The forest plays little part in The Lord of the Rings, but is important in The Hobbit for both atmosphere and plot.[5] It was renamed when "the shadow of Dol Guldur", namely the power of Sauron, fell upon the forest, and people began to call it Taur-nu-Fuin (Sindarin: "forest under deadly nightshade" or "forest under night", i.e. "mirk wood") and Taur-e-Ndaedelos (Sindarin: "forest of great fear").[5][8]

In The Hobbit, Bilbo Baggins, with Thorin Oakenshield and his band of Dwarves, attempt to cross Mirkwood during their quest to regain their mountain Erebor and its treasure from Smaug the dragon. One of the Dwarves, the fat Bombur, falls into the Enchanted River and has to be carried, unconscious, for the following days. Losing the Elf-path, the party becomes lost in the forest and is captured by giant spiders.[T 14] They escape, only to be taken prisoner by King Thranduil's Wood-Elves.[T 15] The White Council flushes Sauron out of his forest tower at Dol Guldur, and as he flees to Mordor his influence in Mirkwood diminishes.[T 16]

Years later, Gollum, after his release from Mordor, is captured by Aragorn and brought as a prisoner to Thranduil's realm. Out of pity, they allow him to roam the forest under close guard, but he escapes during an Orc raid. After the downfall of Sauron, Mirkwood is cleansed by the elf-queen Galadriel and renamed Eryn Lasgalen, Sindarin for "Wood of Greenleaves". Thranduil's son, Legolas, leaves Mirkwood for Ithilien.[T 17] The wizard Radagast lived at Rhosgobel on the western eaves of Mirkwood,[9] as depicted in the film The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey.[10]

Literary philology

The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey noted that the motivation that drove 19th-century philologists to meticulous scrutiny of linguistic theorems of "language-change, sound-shifts and ablaut-gradations"[1] was the excitement of speculating about the wild, primitive Northern forest, the Myrkviðr inn ókunni ("the pathless Mirkwood") and the secret roads across it.[1] Shippey described how "romantically inspired philological interpretations of Myrkviðr"[5] had been made not just by Tolkien but before him by the folklorist Jacob Grimm and the artist and fantasy writer William Morris. These, Shippey argued, helped them to build their own reconstructions of supposed or wholly imaginary cultures. Grimm proposed that the name derived from Old Norse mark (boundary) and mǫrk (forest), both, he supposed, from an older word for wood, perhaps at the dangerous and disputed boundary of the kingdoms of the Huns and the Goths.[5][12]

Morris's Mirkwood is named in his 1899 fantasy novel House of the Wolfings,[T 2] and a similar large dark forest is the setting in The Roots of the Mountains, again marking a dark and dangerous forest.[5] Tolkien had access to more modern philology than Grimm, with proto-Indo-European mer- (to flicker [dimly]) and *merg- (mark, boundary), and places the early origins of both the Men of Rohan and the hobbits there.[5] The Tolkien Encyclopedia remarks also that the Old English Beowulf mentions that the path between the worlds of men and monsters, from Hrothgar's hall to Grendel's lair, runs ofer myrcan mor (across a gloomy moor) and wynleasne wudu (a joyless wood).[5]

Shippey, looking back at the philological evidence, concluded that while the early philologists were driven to some extent by a romantic excitement, their enthusiasm was guided by "a rigorous and academic discipline".[11] He notes that Norse legend does in fact yield two placenames which may well localise the Myrkviðr to the borderlands between the Goths and the Huns of the 4th century. The Atlakviða ("The Lay of Atli", in the Elder Edda) and the Hlöðskviða ("The Battle of the Goths and Huns", in Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks) both mention that the Mirkwood was beside the Danpar, the River Dnieper, which runs from Belarus through Ukraine to the Black Sea. The Hlöðskviða states explicitly in the same passage that the Mirkwood was in Gothland. The Hervarar saga also mentions Harvaða fjöllum, "the Harvad fells". Shippey writes that modern linguistics, applying Grimm's Law for the shifting of consonants, reconstructs "Harvad" as *Karpat, with the strong suggestion that the "Karpat fells" are the Carpathian Mountains.[11] These form an arc to the west of the Dnieper, running from Austria and the Czech Republic down to Romania.[13]

Influence

Tolkien's estate disputed the right of novelist Steve Hillard "to use the name and personality of JRR Tolkien in the novel" Mirkwood: A Novel About JRR Tolkien.[14] The dispute was settled in May 2011, requiring the printing of a disclaimer.[15]

A rock music group named Mirkwood was formed in 1971; their first album in 1973 had the same name. A band in California used the same name in 2005.[16]

Tolkien's forests were the subject of a programme on BBC Radio 3, with Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough and the folk singer Mark Atherton.[17][18]

Literary holidays in the Forest of Dean have been sold on the basis that the area inspired Tolkien, who often went there, to create Mirkwood and other forests in his books.[19]

See also

References

Primary

- This list identifies each item's location in Tolkien's writings.

- Scott, Walter (1814). Waverley; or, 'Tis Sixty Years Since. In Three Volumes. Archibald Constable.

- Morris, William (1904) [1889]. The House of the Wolfings. Longmans, Green, and Co. p. start of chapter 1.

- The Lost Road and Other Writings, King Sheave, 91

- The Fall of Arthur, pp. 19 & 22

- The Silmarillion, "Quenta Silmarillion: Of the Ruin of Beleriand and the Fall of Fingolfin"

- The Lays of Beleriand, p. 36, "but dread they know of the Deadly Nightshade and in haste only do they hie that way."

- The Silmarillion, Index entry "Beleriand": "Beleriand was broken in the turmoils at the end of the First Age, and invaded by the sea, so that only Ossiriand (Lindon) remained." See pages 120-124, 252, 285-286

- The Hobbit, ch. 7 "Queer Lodgings"

- The Silmarillion, "Of the Rings of Power and the Third Age"

- The Fellowship of the Ring and The Two Towers, Fold-out maps

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2 ch. 6 "Lothlórien"

- The Two Towers, book 4, ch. 9 "Shelob's Lair"

- The Hobbit, ch. 8, "Flies and Spiders"

- The Hobbit, ch. 8 "Flies and Spiders"

- The Hobbit, ch. 9 "Barrels Out of Bond"

- The Fellowship of the Ring, book 2, ch. 2 "The Council of Elrond"

- The Return of the King book 6 ch. 4, and Appendix B "Later Events"

Secondary

- Shippey, Tom (2014). The Road to Middle-Earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology. HarperCollins. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-547-52441-2.

- The New York Times Book Review, The Hobbit, by Anne T. Eaton, March 13, 1938, "After the dwarves and Bilbo have passed ...over the Misty Mountains and through forests that suggest those of William Morris's prose romances." (emphasis added)

- Lobdell, Jared [1975]. A Tolkien Compass. La Salle, IL: Open Court. ISBN 0-87548-316-X. p. 84, "only look at The Lord of the Rings for the briefest of times to catch a vision of ancient forests, of trees like men walking, of leaves and sunlight, and of deep shadows."

- Orth, John V. (2019). "Mirkwood". Mythlore. 38 (1 (Fall/Winter)): 51–53.

- Evans, Jonathan (2006). "Mirkwood". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 429–430. ISBN 0-415-96942-5.

- Rateliff, John D. (2007). "Part 2, The Fifth Phase, Timelines and Itinerary (ii)". The History of The Hobbit. HarperCollins. p. 821. ISBN 0-00-725066-5.

- "Rings, dwarves, elves and dragons: J. R. R. Tolkien's Old Norse influences". Institute for Northern Studies, University of the Highlands and Islands [of Scotland]. 9 October 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Foster, Robert (1971). A Guide to Middle Earth. Ballantine Books (Random House). pp. 174, 251.

- Birns, Nicholas (15 October 2007). "The Enigma of Radagast: Revision, Melodrama, and Depth". Mythlore. 26 (1). Article 1.

- Loinaz, Alexis L. (14 December 2012). "The Hobbit: A Who's-Who Guide to Kick Off An Unexpected Journey". Enews. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Shippey, Tom (2007). Goths and Huns: The Rediscovery of the Northern Cultures in the Nineteenth Century. Roots and Branches. Walking Tree Publishers. pp. 115–136. ISBN 978-3905703054.

- Shippey, Tom. "Goths and Huns: the rediscovery of the Northern cultures in the nineteenth century". in The Medieval Legacy: A Symposium. ed. Andreas Haarder et al. Odense University Press, 1982. pages 51-69.

- About the Carpathians - Carpathian Heritage Society Archived 6 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Alberge, Dalya (26 February 2011). "JRR Tolkien novel Mirkwood in legal battle with author's estate". The Guardian.

- Gardner, Eriq (2 May 2011). "JRR Tolkien Estate Settles Dispute Over Novel Featuring Tolkien As Character". The Hollywood Reporter.

- "Mirkwood". Play it yet. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "BBC Radio Programme on Tolkien's Forest: Mirkwood". Tolkien Society. 16 October 2018. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Barraclough, Eleanor Rosamund (9 September 2019). "Mirkwood | Forests". BBC Radio 3. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "'H' is for Hobbit…". Classic British Hotels. Archived from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

Sources

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (2013). The Fall of Arthur. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-748994-7.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937), Douglas A. Anderson (ed.), The Annotated Hobbit, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002), ISBN 0-618-13470-0

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1985), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Lays of Beleriand, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-39429-5

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1987), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Lost Road and Other Writings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-45519-7

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Fellowship of the Ring, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08254-4

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954), The Two Towers, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08254-4

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955), The Return of the King, The Lord of the Rings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 1987), ISBN 0-395-08256-0

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977), Christopher Tolkien (ed.), The Silmarillion, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-25730-1

.jpg)