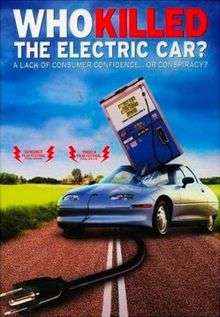

Who Killed the Electric Car?

Who Killed the Electric Car? is a 2006 documentary film that explores the creation, limited commercialization, and subsequent destruction of the battery electric vehicle in the United States, specifically the General Motors EV1 of the mid-1990s. The film explores the roles of automobile manufacturers, the oil industry, the federal government of the United States, the California government, batteries, hydrogen vehicles, and consumers in limiting the development and adoption of this technology.

| Who Killed the Electric Car? | |

|---|---|

DVD cover | |

| Directed by | Chris Paine |

| Produced by | Jessie Deeter |

| Written by | Chris Paine |

| Starring | Tom Hanks (from a recording) Mel Gibson Chelsea Sexton Ralph Nader Joseph J. Romm Phyllis Diller |

| Narrated by | Martin Sheen |

| Music by | Michael Brook |

| Cinematography | Thaddeus Wadleigh |

| Edited by | Michael Kovalenko Chris A. Peterson |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics |

Release date | Sundance Film Festival January 23, 2006 United States June 28, 2006 United Kingdom August 4, 2006 Australia November 2, 2006 |

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1,764,304 (worldwide)[1] |

After a premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, it was released theatrically by Sony Pictures Classics in June 2006 and then on DVD by Sony Pictures Home Entertainment on November 14, 2006.

A follow-up documentary, Revenge of the Electric Car, was released in 2011.[2]

Topics addressed

The film deals with the history of the electric car, its modern development, and commercialization. The film focuses primarily on the General Motors EV1, which was made available for lease mainly in Southern California, after the California Air Resources Board (CARB) passed the zero-emissions vehicle (ZEV) mandate in 1990 which required the seven major automobile suppliers in the United States to offer electric vehicles in order to continue sales of their gasoline powered vehicles in California. Nearly 5000 electric cars were designed and manufactured by Chrysler, the Ford Motor Company, General Motors (GM), Honda, Nissan, and Toyota; and then later destroyed or donated to museums and educational institutions. Also discussed are the implications of the events depicted for air pollution, oil dependency, Middle East politics, and global warming.

The film details the California Air Resources Board's reversal of the mandate after relentless pressure and suits from automobile manufacturers, continual pressure from the oil industry, orchestrated hype over a future hydrogen car, and finally the George W. Bush administration.

A portion of the film details GM's efforts to demonstrate to California that there was no consumer demand for their product, and then to take back every EV1 and destroy them. A few were disabled and given to museums and universities, but almost all were found to have been crushed. GM never responded to the EV drivers' offer to pay the residual lease value; $1.9 million was offered for the remaining 78 cars in Burbank, California before they were crushed. Several activists, including actresses Alexandra Paul and Colette Divine, were arrested in the protest that attempted to block the GM car carriers taking the remaining EV1s off to be crushed.

The film explores some of the motives that may have pushed the auto and oil industries to kill off the electric car. Wally Rippel offers, for example, that the oil companies were afraid of losing their monopoly on transportation fuel over the coming decades; while the auto companies feared short-term costs for EV development and long-term revenue loss because EVs require little maintenance and no tuneups. Others explained the killing differently. GM spokesman Dave Barthmuss argued it was lack of consumer interest due to the maximum range of 80–100 miles per charge, and the relatively high price.

The film also showed the failed attempts by electric car enthusiasts trying to combat auto industry moves, and save the surviving vehicles. Towards the end of the film, a deactivated EV1 car #99 is found in the garage of Petersen Automotive Museum, with former EV sales representative, Chelsea Sexton, invited for a visit.

The film also explores the future of automobile technologies including a deeply critical look at hydrogen vehicles, an upbeat discussion of plug-in hybrids, and examples of other developing EV technologies such as the Tesla Roadster (2008), released on the market two years after the film.

Interviews

The film features interviews with celebrities who drove the electric car, such as Ed Begley Jr., Mel Gibson, Tom Hanks, Peter Horton, and Alexandra Paul. It also features interviews with a selection of prominent American political figures including Jim Boyd, S. David Freeman, Frank Gaffney, Alan C. Lloyd (Chairman of the California Air Resources Board), Alan Lowenthal, and Ralph Nader. Included are interviews with Edward H. Murphy (representative of the American Petroleum Institute), and James Woolsey (former Director of Central Intelligence), as well as news footage from the development, launch and marketing of EVs.

The film also features interviews with some of the engineers and technicians who led the development of modern electric vehicles and related technologies, such as Wally Rippel, Chelsea Sexton, Alec Brooks, Alan Cocconi, Paul MacCready, Stan and Iris M. Ovshinsky, and other experts such as Joseph J. Romm (author of Hell and High Water and The Hype about Hydrogen). Romm gives a presentation intended to show that the government's "hydrogen car initiative" is a bad policy choice and a distraction that is delaying the exploitation of more promising technologies, such as electric and hybrid cars which could reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase America's energy security. Also featured in the film are spokespersons for the automakers, such as GM's Dave Barthmuss, a vocal opponent of the film and the EV1, John Wallace from Ford, and Bill Reinert from Toyota.

Production and release

The film was written and directed by Chris Paine, and produced by Jessie Deeter, and executive produced by Tavin Marin Titus, Richard D. Titus of Plinyminor and Dean Devlin, Kearie Peak, Mark Roskin, and Rachel Olshan of Electric Entertainment.

The film features a film score composed by Michael Brook. It also features music by Joe Walsh, DJ Harry and Meeky Rosie. Jeff Steele, Kathy Weiss, Natalie Artin and Alex Gibney were also part of the producing team.

The documentary was featured at the Sundance, San Francisco, Tribeca, Los Angeles, Berlin, Deauville, and Wild and Scenic Environmental film festivals and was released in theaters worldwide in June 2006.

The suspects

The later portion of the film is organized around the following hypothesized culprits in the downfall of the electric car:

American consumers

While few American consumers never heard of the electric cars in California, those who did were not necessarily critical mass for this new technology. Thanks to lower gas prices and infatuation with sport utility vehicles (SUVs), few people sought out this new technology. While some were fans (as chronicled in the film), many more needed time to consider the advantages and disadvantages of these new cars; whether freedom from oil or with the perceived limitations of a city car with a 100-mile range. Although allegations are made about consumers by industry representatives in the film, perhaps explaining the film's "guilty" verdict, the actual consumers interviewed in the film were either unaware that an electric car was ever available to try, or dismayed that they could no longer obtain one.

Batteries

In a bit of an unexpected turn, the film's sole "not-guilty" suspect is batteries, one of the chief culprits if one were to ask the oil or auto industries. At the time GM's EV1 came to market, it came with a lead acid battery with a range of 60 miles. The film suggests that since the average driving distance of Americans in a day is 30 miles or less, for 90% of Americans, electric cars would work as a daily commute car or second car.

The second generation EV1 (and those released by Honda, Toyota, and others) from 1998 to the end of the program, featured nickel-metal-hydride or even lithium-ion (Nissan) batteries with a range of 100 or more miles. The film documents that the company which had supplied batteries for EV1, Ovonics, had been suppressed from announcing improved batteries, with double the range, lest CARB be convinced that batteries were improving. Later, General Motors sold the supplier's majority control share to the Chevron Corporation and Cobasys.

As part of the not-guilty verdict, the famed engineer Alan Cocconi explains that with laptop computer lithium ion batteries, the EV1 could have been upgraded to a range of 300 miles per charge. He makes this point in front of his T-Zero prototype, the car that inspired the Tesla Roadster (2008).

Oil companies

The oil industry, through its major lobby group the Western States Petroleum Association, is brought to task for financing campaigns to kill utility efforts to build public car charging stations. Through astroturfing groups like "Californians Against Utility Abuse" they posed as consumers instead of the industry interests they actually represented.

Mobil and other oil companies are also shown to be advertising directly against electric cars in national publications, even when electric cars seem to have little to do with their core business. At the end of the film, Chevron bought patents and controlling interest in Ovonics, the advanced battery company featured in the film, ostensibly to prevent modern NiMH batteries from being used in non-hybrid electric cars.

The documentary also refers to manipulation of oil prices by overseas suppliers in the 1980s as an example of the industry working to kill competition and keep customers from moving toward alternatives to oil.

Car companies

With GM as its primary example, the film documents that car makers engaged in both positive and negative marketing of the electric car as its intentions toward the car and California legislation changed. In earlier days, GM ran Super Bowl commercials produced by Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) for the EV1. In later days it ran "award winning" doomsday-style advertising featuring the EV1 and ran customer surveys which emphasized drawbacks to electronic vehicle technology which were not actually present in the EV1.[3] (As a side note, CARB officials were quoted claiming that they removed their zero emission vehicle quotas in part because they gave weight to such surveys purportedly showing no demand existing for the EV1s.) Other charges raised on GM included sabotaging their own product program, failing to produce cars to meet existing demand, and refusing to sell cars directly (it only leased them).

The film also describes the history of automaker efforts to destroy competing technologies, such as their destruction through front companies of public transit systems in the United States in the early 20th century. In addition to EV1, the film also depicted how Toyota RAV4 EV, and Honda EV Plus were being cancelled by their respective car companies. The crushing of Honda EV Plus only gained attention after appearing quite by accident on an episode of PBS's California's Gold with Huell Howser.

In an interview with retired GM board member Tom Everhart, the film points out that GM killed the EV1 to focus on more immediately profitable enterprises such as its Hummer and truck brands, instead of preparing for future challenges. Ralph Nader, in a brief appearance, points out that auto makers usually only respond to government regulation when it comes to important advances whether seat belts, airbags, catalytic converters, mileage requirements or, by implication, hybrid/electric cars. The film suggests Toyota supported the production of Toyota Prius hybrid in part as a response to Bill Clinton's Partnership for a New Generation of Vehicles and other U.S. Government pressure that was later dropped.

Though GM cited cost as a deterrent to continuing with the EV1, the film interviewed critics contending that the cost of batteries and electric vehicles would have been reduced significantly if mass production began, due to economies of scale. There is also discussion about electric cars threatening dealer profits since they have so few service requirements—no tuneups, no oil changes, and less frequent brake jobs because of regenerative braking.

U.S. government

While not overtly political, the film documents that the federal government of the United States under the Presidency of George W. Bush joined the auto-industry suit against California in 2002. This pushed California to abandon its ZEV mandate regulation. The film notes that Bush's chief of staff Andrew Card had recently been head of the American Automobile Manufacturers Alliance in California and then joined the White House with Dick Cheney, Condoleezza Rice, and other federal officials who were former executives or board members of oil and auto companies. By failing to increase mileage standards in a meaningful way since the 1970s and now interfering in California, the federal government had again served short-term industry interests at the expense of long-range leadership on issues of oil dependency and cleaner cars.

California Air Resources Board

In 2003, the California Air Resources Board (CARB), headed by Democrat Alan Lloyd, finally caved to industry pressure and drastically scaled back the ZEV mandate. CARB had previously defended the regulation for more than 12 years.

While championing CARB's efforts on behalf of California's with its 1990 mandate (and other regulations over the years), the film suggests Lloyd may have had a conflict of interest, as the director of the California Fuel Cell Partnership. The ZEV change allowed a marginal amount of hydrogen fuel cell cars to be produced in the future, versus the immediate continued growth of its electric car requirement. Footage shot in the meetings showed Lloyd shutting down battery electric car proponents while giving the car makers all the time they wanted to make their points.

Hydrogen fuel cell

The hydrogen fuel cell was presented by the film as an alternative that distracts attention from the real and immediate potential of electric vehicles to an unlikely future possibility embraced by auto makers, oil companies and a pro-business administration in order to buy time and profits for the status quo. The film corroborates the claim that hydrogen vehicles are a mere distraction by stating that "A fuel cell car powered by hydrogen made with electricity uses three to four times more energy than a car powered by batteries" and by interviewing Joseph J. Romm, the author of The Hype about Hydrogen, who lists five problems he sees with hydrogen vehicles: High cost, limits on driving range due to current materials, high costs of hydrogen fuel, the need for entirely new fueling compounds, and competition from other technologies in the marketplace, such as hybrids.

The price of hydrogen has since come down to $4–6/kg (without carbon sequestering) due to reduction in the price of natural gas as a feedstock for steam reforming owing to the proliferation of hydraulic fracturing of shales.[4] A kilo of hydrogen has the same energy yield as a gallon of gasoline although production currently creates 12.5 kg CO2, 39% more than the 8.91 kg CO2 from a gasoline gallon.[4]

Response from General Motors

General Motors (GM) responded in a 2006 blog post titled "Who Ignored the Facts About the Electric Car?"[5] written by Dave Barthmuss of GM's communications department. In his June 15, 2006 post—published 13 days before the film was released in the U.S.—Barthmuss claims not to have seen the film, but believes "there may be some information that the movie did not tell its viewers." He repeats GM's claims that, "despite the substantial investment of money and the enthusiastic fervor of a relatively small number of EV1 drivers — including the filmmaker — the EV1 proved far from a viable commercial success."

He submits it is "good news for electric car enthusiasts" that electric vehicle technology since the EV1 was still being used. It was used in two-mode hybrid, plug-in hybrid, and fuel cell vehicle programs.

Barthmuss also cites "GM's leadership" in flex-fuel vehicles development, hydrogen fuel cell technology, and their new "active fuel management" system which improve fuel economy, as reasons they feel they are "doing more than any other automaker to address the issues of oil dependence, fuel economy and emissions from vehicles."

Responding to the film's harsh criticisms for discontinuing the EV1, Barthmuss outlines GM's reasons for doing so, implying that GM did so due to inadequate support from parts suppliers, as well as poor consumer demand despite "significant sums (spent) on marketing and incentives to develop a mass market for it." Barthmuss claimed he personally regretted the way the decision not to sell the EV1s was handled, but stated it was because GM would no longer be able to repair it or "guarantee it could be operated safely over the long term," with lack of available parts making "future repair and safety of the vehicles difficult to nearly impossible." He also claimed that "no other major automotive manufacturer is producing a pure electric vehicle for use on public roads and highways."

In March 2009, however, outgoing CEO of GM Rick Wagoner said the biggest mistake he ever made as chief executive was killing the EV1 car and failing to direct more resources to electrics and hybrids after such an early lead in this technology.[6] GM has since championed its electric-car expertise as a key factor in development of its 2010 Chevrolet Volt, Chevy Spark EV, and the Chevrolet Bolt.

Reception

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an 89% approval rating based on 105 reviews, with an average rating of 7.19/10.[7] Metacritic, another review collator, reported a positive rating of 70, based on 28 reviews polled.[8]

Manohla Dargis of The New York Times wrote, "It's a story Mr. Paine tells with bite. In 1996 a Los Angeles newspaper reported that 'the air board grew doubtful about the willingness of consumers to accept the cars, which carry steep price tags and have a limited travel range.' Mr. Paine pushes beyond this ostensibly disinterested report, suggesting that one reason the board might have grown doubtful was because its chairman at the time, Alan C. Lloyd, had joined the California Fuel Cell Partnership."[9]

Michael Rechtshaffen of The Hollywood Reporter noted Alan Lloyd's conflict of interest in the film.[10]

Pete Vonder Haar of Film Threat commented, "Boasting a particularly articulate and colorful bunch of noncelebrity talking heads, including former president Jimmy Carter, energy adviser S. David Freeman and Bill Reinert, the straight-shooting national manager of advanced technologies for Toyota who doesn't exactly sing the praises of the much-touted hydrogen fuel cell, the lively film maintains its challenging pace."[11]

Matt Coker of OC Weekly stated, "Like most documentaries, 'Who Killed the Electric Car?' works best when it sticks to the facts. Showing us the details about the California Air Resources Board caving in to the automakers and repealing their 1990 Zero Emissions Mandate, for example, is much more effective than coverage of some goofy mock funeral for the EV1 with Ed Begley Jr. providing the eulogy. As most of the lazy media, prodded by the shameless oil men in the White House, spin their wheels over false 'solutions' like hybrids and biodiesel and hydrogen and ethanol and ANWR, Korthof and his all-electric army continue to boost EV technology." Coker also interviewed EV activist Doug Korthof, who stated, "We don't deserve the catastrophe in Iraq, and the two madmen arguing over oil supply lines seem intent on martyrdom for Iraq in a widening war. With EV, we need not get involved in seizing and defending the oil supplies of the Mideast; nor need we maintain fleets, bomb and incarcerate people we can't stand, give foreign aid to oily dictators, and so on. It's not anything to laugh about."[12]

The film won the 2006 MountainFilm in Telluride (Colorado, USA) Special Jury Prize, the Canberra International Film Festival Audience Award, and also nominated for Best Documentary in the 2006 Environmental Media Awards, Best Documentary in Writers Guild of America, 2007 Broadcast Film Critics Association Best Documentary Feature. In 2008 socially conscious musician Tha truth released a song that summarized the film on the CD Tha People's Music.

See also

|

|

References

- "Who Killed the Electric Car? (2006)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- "Revenge of the Electric Car: World Premiere Announced". Revenge of the Electric Car website. 2011-03-14. Archived from the original on 2011-03-17. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- Welch, David (August 14, 2000). "The Eco-Cars". BusinessWeek. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2012-05-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Who Ignored the Facts About the Electric Car? blog post copy in PDF format

- Neil, Dan. "The Rick Wagoner vehicles: Hits and misses", LA Times, March 31, 2009

- [url=http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/who_killed_the_electric_car/ Who Killed the Electric Car?], Rotten Tomatoes, accessed December 28, 2010

- MetaCritic review

- Dargis, Manohla. "'Who Killed the Electric Car?': Some Big Reasons the Electric Car Can't Cross the Road", The New York Times, June 28, 2006

- Rechtshaffen, Michael. Hollywood Reporter Review, The Hollywood Reporter Archived July 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Vonder Haar, Pete. "WHO KILLED THE ELECTRIC CAR?" Film Threat, January 25, 2006

- Coker, Matt. "Baby You Can Still Drive My Electric Car", OC Weekly, May 16, 2006

External links

- Who Killed the Electric Car? - Official website

- Who Killed the Electric Car? at the Sony Classics website

- Who Killed the Electric Car? on IMDb

- PBS interview with director Chris Paine, including video

- Art Film Talk #14 Chris Paine – interview with director Chris Paine (audio)

- Article on MSNBC about the removal of the last remaining operational EV1 from the museum just one week before the film's opening

- Watch: Director Chris Paine interviewed at the Woods Hole Film Festival on independentfilm.com