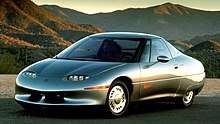

General Motors EV1

The General Motors EV1 was an electric car produced and leased by General Motors from 1996 to 1999.[6] It was the first mass-produced and purpose-designed electric vehicle of the modern era from a major automaker and the first GM car designed to be an electric vehicle from the outset.[7]

| General Motors EV1 | |

|---|---|

_cropped.jpg) | |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | General Motors |

| Also called | GM EV1 |

| Production |

|

| Assembly | GM Lansing Craft Centre, Lansing, Michigan, U.S. |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Electric subcompact coupé |

| Body style | 2-seat, 2-door coupé |

| Layout | Transverse front-motor, front-wheel drive |

| Powertrain | |

| Electric motor |

|

| Transmission | Single-speed reduction integrated with motor and differential |

| Battery | Early vehicles 16.5–18.7 kWh lead-acid, later versions 26.4 kWh Nickel Metal Hydride (NiMH) |

| Electric range | |

| Plug-in charging | 6.6 kW Magne Charge inductive converter |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 98.9 in (2,510 mm) |

| Length | 169.7 in (4,310 mm)[5] |

| Width | 69.5 in (1,770 mm)[5] |

| Height | 50.5 in (1,280 mm) |

| Curb weight |

|

| Chronology | |

| Predecessor | GM Impact (prototype) |

| Successor |

|

The decision to mass-produce an electric car came after GM received a favorable reception for its 1990 Impact electric concept car, upon which the design of the EV1 drew heavily. Inspired partly by the Impact's perceived potential for success, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) subsequently passed a mandate that made the production and sale of zero-emissions vehicles (ZEV) a requirement for the seven major automakers selling cars in the United States to continue to market their vehicles in California.

The EV1 was made available through limited lease-only agreements, initially to residents of the cities of Los Angeles, California, and Phoenix and Tucson, Arizona.[8] EV1 lessees were officially participants in a "real-world engineering evaluation" and market study into the feasibility of producing and marketing a commuter electric vehicle in select U.S. markets undertaken by GM's Advanced Technology Vehicles group.[9][10] The cars were not available for purchase, and could be serviced only at designated Saturn dealerships. Within a year of the EV1's release, leasing programs were also launched in San Francisco and Sacramento, California, along with a limited program in the state of Georgia.

While customer reaction to the EV1 was positive, GM believed that electric cars occupied an unprofitable niche of the automobile market, and ended up crushing most of the cars, regardless of protesting customers.[11] Furthermore, an alliance of the major automakers litigated the CARB regulation in court, resulting in a slackening of the ZEV stipulation, permitting the companies to produce super-low-emissions vehicles, natural gas vehicles, and hybrid cars in place of pure electrics. The EV1 program was subsequently discontinued in 2002, and all cars on the road were repossessed. Lessees were not given the option to purchase their cars from GM, which cited parts, service, and liability regulations.[6] The majority of the repossessed EV1s were crushed, and about 40 were delivered to museums and educational institutes with their electric powertrains deactivated, under the agreement that the cars were not to be reactivated and driven on the road. About 20 units were donated to overseas institutions. In 2016, the TV show Jay Leno's Garage presented an intact EV1 as part of the collection of filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola. The only intact EV1 was donated to the Smithsonian Institution.[12]

The EV1's discontinuation remains controversial, with electric car enthusiasts, environmental interest groups and former EV1 lessees accusing GM of self-sabotaging its electric car program to avoid potential losses in spare parts sales (sales forced by government regulations), while also blaming the oil industry for conspiring to keep electric cars off the road.[6] As a result of the forced repossession and destruction of the majority of EV1s, an intact and working EV1 is one of the rarest cars from the 1990s.

History

Origins

In January 1990, GM chairman Roger Smith demonstrated the Impact, an electric concept car, at the 1990 LA Auto Show. GM preferred a production rate of 100,000 cars per year, rather than 20,000.[13] The car had been developed by electric vehicle company AeroVironment, using design knowledge gained from GM's participation in the 1987 World Solar Challenge, a trans-Australia race for solar vehicles, with the Sunraycer, which went on to win the competition.[14] Alan Cocconi of AC Propulsion designed and built the original drive system electronics for the Impact, and the design was later refined by Hughes Electronics. On April 18, 1990,[15] Smith announced that the Impact would become a production vehicle with a goal of 25,000 vehicles.[16][17] The Impact reached a top speed of 183 mph (295 km/h).[18]

Impressed by the viability of the Impact, and motivated by GM's intent to produce the Impact in at least 5,000 vehicles,[19] the California Air Resources Board (CARB) moved on a large environmental initiative, ruled that each of the U.S.'s seven largest carmakers—the largest of which was GM—would be required to make 2% of its fleet emission-free by 1998, 5% by 2001, and 10% by 2003, in accordance with consumer demand, in order to continue to sell cars in California.[16] The board stated the mandate was intended to combat California's poor air quality, which at the time was worse than the other 49 states combined.[20] Other members of what was then the American Automobile Manufacturers Association, along with Toyota, Nissan[21] and Honda, each also developed a prototype zero-emissions vehicle in response to the new mandate.

In 1994, GM began PrEView, a program whereby 50 handbuilt Impact electric cars would be lent to drivers for periods of one to two weeks, under the agreement that their experiences would be logged.[16] Volunteers had to own a garage where a high-current charging unit could be installed by an electric company.[22] Program supervisor Sean McNamara said that he expected at most eighty volunteers in the Los Angeles area, but was forced to close the phone lines after 10,000 people called in.[20] In New York City, 14,000 callers responded before the lines were closed.[22][23] Driver response to the cars was favorable, as were reviews by the automotive press. According to Motor Trend, "The Impact is precisely one of those occasions where GM proves beyond any doubt that it knows how to build fantastic automobiles. This is the world's only electric vehicle that drives like a real car." Automobile called the car's ride and handling "amazing," praising its "smooth delivery of power". That year, a modified Impact set a land speed record for production electric vehicles of 183 mph (295 km/h). However, according to a front-page article in The New York Times, GM was less than pleased with the prospect of having developed a successful electric car:

General Motors is preparing to put its electric vehicle act on the road, and planning for a flop. With pride and pessimism, the company, the furthest along of the Big Three in designing a mass-market electric car, says that in the face of a California law that requires that 2 percent of new cars be "zero emission" vehicles beginning in 1997, it has done its best but that the vehicle has come up short.... Now it hopes that lawmakers and regulators will agree with it and postpone or scrap the deadline.[22]

According to the report, GM viewed the PrEView program as a failure, evidence that the electric car was not yet viable, and that the CARB regulations should be withdrawn. Dennis Minano, GM's Vice President for Energy and Environment, questioned whether consumers desired electric vehicles.[22] Robert James Eaton, chairman of Chrysler, also questioned whether the market was ready for electric cars, and said in 1994, "... if the law is there, we'll meet it... at this point of time, nobody can forecast that we can make an electric car."[22] The negative positions taken by the automakers was criticized by Thomas C. Jorling, the Commissioner of Environmental Conservation for New York State, which had adopted the California emission program. According to Jorling, consumers had demonstrated tremendous interest in electric cars, but automakers did not want to render obsolete their multibillion-dollar investments in internal combustion engine technology.[22]

Release of Gen I and initial reaction

Work on the GM electric car program continued after the end of PrEView. While the original 50 Impact cars were destroyed after testing was finished,[16] the design had evolved into the GM EV1 by 1996. The EV1 would be the first GM car in history to wear a "General Motors" nameplate, instead of one of GM's marques.[16] The first-generation, or "Gen I" car, which would be powered by lead-acid batteries and had a stated range of 70 to 100 miles; 660 cars, painted dark green, red, and silver were produced.[16][24]

The cars were made available via a leasing program, with the option to purchase the cars specifically disallowed by a contractual clause (the suggested retail price was quoted as $34,000[25]). Saturn was put in charge of leasing and service for the EV1.[26] Analysts estimated a market of 5,000 to 20,000 cars per year.[27]

In similar fashion to the PrEView program, lessees were pre-screened by GM, with only residents of Southern California and Arizona initially eligible for participation. Leasing rates for the EV1 ranged from $399 to $549 a month.[28] The car's launch was a media event, accompanied by an $8 million promotional campaign, which included prime-time TV advertising, billboards, a web site, and an appearance at the premiere of the Sylvester Stallone film Daylight.[25] The first lessees included celebrities, executives and politicians. A total of 40 EV1 leases were signed at the release event, with GM estimating that it would lease 100 cars by the end of the year. Deliveries began on December 5, 1996.[25]

.jpg)

Joe Kennedy, vice president of marketing for GM marque Saturn, accepted concerns regarding the EV1's cost, the outdated lead-acid battery technology, and the car's limited range, saying "Let us not forget that technology starts small and grows slowly before technology improves and costs go down."[25]

Some anti-taxation groups were against the exemptions and tax credits that EV1 lessees received, which they said constituted government-subsidized motoring for affluent professionals.[25] Some of these groups, such as fake consumer organization Californians Against Utility Company Abuse (which mounted opposition to the use of taxpayer dollars to build public EV charging stations), were themselves accused of receiving their funding from oil companies interested in keeping gasoline cars on the roads.[29][30] Concerns were also raised that the car had received only a limited launch, because GM had made a deal with CARB to delay the implementation of the first phase of the ZEV program, which had been scheduled to go into effect in 1998.[31]

In the first year after release, GM leased only 288 cars.[32] However, by 1999, the brand manager for the EV1 program, Ken Stewart, described the response of the car's drivers as "wonderfully-manical loyalty."[33] The lessees had integrated the EV1 into their lifestyle, making the car less a novelty item and more a primary source of transportation.[33]

Some EV1 enthusiasts believed that GM was demonstrating ambivalence towards promotion of the EV1 after its initial release. While one of the first EV1 TV spots was nominated for an Emmy Award, later advertising was limited to direct mail and print and TV ads in niche channels. While GM remained officially committed to the electric vehicle, enthusiasts were concerned that low public interest would result in the program being scrapped.

One driver, Marvin Rush, a cinematographer for the TV series Star Trek: Voyager, became so concerned that he spent $20,000 of his own funds to produce and air four unofficial radio commercials for the car. While the automaker was initially opposed to the action, it later changed its position, announcing that it would make the spots official and reimburse Rush. The company spent $10 million on EV1 advertising in 1997, and promised to increase that amount by $5 million the following year.[34]

Second generation: 1999–2003

For the 1999 model year, GM released a Gen II version of the EV1. Major improvements included lower production costs, quieter operation, extensive weight reduction, and the advent of a nickel–metal hydride battery (NiMH).[16] The Gen II models were initially released with a 60 amp-hour, 312 V (18.7 kWh, 67.3 MJ) Panasonic lead-acid battery pack, a slight improvement over the Gen I power source using the same voltage; later models featured an Ovonics NiMH battery rated at 77 Ah with 343 volts (26.4 kWh, 95.0 MJ). Cars with the lead-acid pack had a range of 80–100 mi (130–160 km), while the NiMH cars could travel 100–140 mi (160–230 km) between charges. For the second-generation EV1, the leasing program was expanded to the cities of San Diego, Sacramento, and Atlanta; monthly payments ranged from $349 to $574.[16] 457 Gen II EV1s were produced by General Motors and leased to customers in the eight months following December 1999.[35] According to some sources, hundreds of drivers wanted to but could not become EV1 lessees.[16]

On March 2, 2000, GM issued a recall for 450 Gen I EV1s. The automaker had determined that a faulty charge port cable could eventually build up enough heat to catch on fire. Sixteen "thermal incidents" and at least one fire occurred as a result of the defect, destroying a car leased by Ron Brauer and Ruth Bygness as it was charging.[36] The recall did not affect second-generation EV1s.[37]

Over the next two years, approximately 200 Gen I EV1s were refitted with NiMH batteries and re-issued to their original lessees on revised two-year leases, including a new limited-mileage clause.[38] Delays were involved due to design complications resulting from the NiMH pack retrofit.[39] As a result, GM offered Gen I drivers the opportunity to terminate their lease at no charge,[40][41] or the chance to transfer the lease to one of the remaining 150 second-generation EV1s — ahead of those already on the waiting list for Gen II models.[42][43]

Cancellation

By 2002, 1,117 EV1s had been produced, though production had ended in 1999, when GM shut down the EV1 assembly line.[30] On February 7, 2002, GM Advanced Technology Vehicles brand manager Ken Stewart notified lessees that GM would be removing the cars from the road,[44] contradicting an earlier statement that GM would in fact not be "taking cars off the road from customers."[45] Drivers feared that their working cars would be destroyed after repossession.[30]

In late 2003, General Motors, then led by CEO Rick Wagoner, officially canceled the EV1 program.[11][46] GM stated that it could not sell enough of the cars to make the EV1 profitable.[47] In addition, the cost of maintaining a parts supply and service infrastructure for the 15-year minimum required by the state of California meant that existing leases would not be renewed, and all the cars would have to be returned to GM's possession.

At least 58 EV1 drivers sent letters and deposit checks to GM, requesting lease extensions at no risk or cost to the automaker. The drivers reportedly agreed to be responsible for the maintenance and repair costs of the EV1, and would allow GM the right to terminate the lease if expensive repairs were needed. On June 28, GM famously refused the offer and returned the checks, which totaled $22,000;[44] By contrast, Honda, which had taken similar actions with its EV+ program, agreed to extend its customers' leases.[30]

In November 2003, GM began reclaiming the cars; about 40 were donated to museums and educational institutions[12] (e.g., Mott Community College in Flint, Michigan[48] and the R. E. Olds Transportation Museum in Lansing, Michigan), albeit with deactivated powertrains meant to keep the cars from ever running again, but the majority were sent to car crushers to be destroyed.[49]

The documentary Who Killed the Electric Car? presents evidence that GM stuck with plans to cancel and scrap the car, despite apparent public interest. The film includes footage of GM employees on the EV1 team discussing a waiting list of people interested in leasing or purchasing EV1s.

In 2003, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times attempted to lease an EV1 from GM, but was told that he "was welcome to join their waiting list (a few thousand), along with undisclosed others, for an indefinite period of time, but his chances of getting a car were slim."[17]

In March 2005 GM spokesman Dave Barthmuss spoke about the EV1 to The Post, "There is an extremely passionate, enthusiastic and loyal following for this particular vehicle... There simply weren't enough of them at any given time to make a viable business proposition for GM to pursue long term."[50]

Critics of GM and proponents of electric vehicles claim that GM feared the emergence of electrical vehicle technology because the cars might cut into their profitable spare parts market, as electric cars have far fewer moving parts than combustion vehicles. Critics further charged that when CARB, in response to the EV1, mandated that electric vehicles make up a certain percentage of all automakers' sales, GM came to fear that the EV1 might encourage unwanted regulation in other states. GM, which was also joined by other automakers, battled against CARB regulations, going as far as to sue CARB in federal court.[30]

At the 2000 hearings, GM claimed that consumers were simply not showing sufficient interest in the EV1 to meet the sales requirements called for by CARB mandates.[30] The American automaker, along with Toyota, cited a study they had commissioned, which showed that customers would only choose an electric car over a gasoline car if it cost a full $28,000 less than a comparable gasoline car. Dr. Kenneth E. Train of UC Berkeley, who conducted the study, stated that given a typical retail price of $21,000 for a RAV4 SUV, "Toyota would have to give the average consumer a free RAV4-EV plus a check for approximately $7,000."[51]

An independent study commissioned by the California Electric Transportation Coalition (CalETC) and conducted by the Green Car Institute and the Dohring Company automotive market research firm found very different results. The study "used the same research methodologies employed by the auto industry to identify markets for its gasoline vehicles".[52] It found the annual consumer market for EVs to be 12–18% of the new light-duty vehicle market in California, amounting to annual sales of between 151,200 and 226,800 electric vehicles,[53] approximately ten times the quantity specified by CARB's mandate. The study, however, took care to note that vehicles would require increased range and be sold at prices close to a regular gasoline sedan rather than the premium then demanded for electric vehicles.[52]

The results of the Toyota-GM study were questioned in light of the success of Toyota's electric RAV4-EV, which retailed at $30,000, though at this price the RAV4 was sold at a net loss.[30]

At the hearings, the automakers also presented the hydrogen vehicle as a better alternative to the gasoline car, bolstered by a recent federal earmark for hydrogen research. Many, including members of the CARB hearing committee, were concerned that this was a bait-and-switch on the automakers' part, in order to make CARB eliminate the EV mandate, and that hydrogen was not as viable an alternative as it was made to seem.[30]

CARB had already rolled back deadlines several times, in light of car companies' unreadiness to meet the ZEV requirement. In 2001, it proposed amendments[54] that would grant automakers credit for producing advanced-technology, partial-zero emission vehicles, such as hybrid cars, in place of battery EVs. However, the industry used the relaxation of the rules to challenge the regulation as a whole.[55]

General Motors and Daimler-Chrysler filed suit against CARB in the US District Court in the Eastern District of California, successfully arguing that CARB's method of determining whether or not a vehicle qualified as an Advanced Technology Partial ZEV (AT PZEV) used the vehicle's fuel economy as one of the standards, in addition to reduced emissions; according to federal law, states are barred from regulating fuel economy in any way. Judge Robert E. Coyle issued a preliminary injunction on June 11 against the CARB, ruling the provision unconstitutional and preventing the implementation of CARB's 2001 amendments.[56] The mandate was modified, with the zero-emission requirement reduced to at least 250 fuel cell or battery-powered vehicles by 2008.[57]

By the end of 2002, no EV-1s remained on the road, as General Motors had repossessed all leased EV-1's from their lessees. One was on display at the Main Street in Motion exhibit at Epcot in Walt Disney World in Lake Buena Vista, Florida. Some other EV-1s repossessed from their lessees were donated to tech schools for disassembly and analysis purposes, never to be put back onto the road.

Reaction

In the aftermath of the program, reactions to the cancellation of the EV1 continued to be mixed. In GM's view, the EV1 was not a failure, but the program was doomed when the expected breakthroughs in battery technology did not take place within the anticipated timeline,[58] citing the lack of availability of the NiMH-technology battery packs, developed by Energy Conversion Devices of Michigan, until late in the production cycle. The batteries improved the EV1's range, but not as dramatically as expected, and came with their own set of problems; a less-efficient charging algorithm had to be used (lengthening charge times), and the batteries heated up more quickly than the lead-acid packs (requiring use of the air conditioner to cool them down, wasting power).[59]

The automaker also cited the elimination of the CARB zero-emissions mandate as a factor in the program's cancellation, though the company was widely accused of lobbying against the mandate in an act of deliberate self-sabotage. The media perspective was far less favorable; in 2006, The Wall Street Journal's Detroit Bureau Chief Joe White said, "The EV1 was a failure, as were other electric vehicles launched in the 1990s to placate California clean-air regulators."[60] This opinion was echoed by TIME magazine, who in 2008 placed the EV1 on their list of "The 50 Worst Cars of All Time".[61]

In light of falling car sales later in the decade, as the world oil and financial crises began to take hold, opinions of the EV1 program began to change. In 2006, former GM Chairman and CEO Rick Wagoner stated that his worst decision during his tenure at GM was "axing the EV1 electric-car program and not putting the right resources into hybrids. It didn't affect profitability, but it did affect image."[62] Wagoner repeated this assertion during an NPR interview after the December 2008 Senate hearings on the U.S. auto industry bailout request.[63]

In the March 13, 2007, issue of Newsweek, "GM R&D chief Larry Burns . . . now wishes GM hadn't killed the plug-in hybrid EV1 prototype his engineers had on the road a decade ago: 'If we could turn back the hands of time,' says Burns, 'we could have had the Chevy Volt 10 years earlier,'"[64] referring to the plug-in hybrid car which is now considered to be the technological and spiritual successor to the EV1. However, in November 2018, GM announced it would stop production of the Chevy Volt in March 2019.[65]

Tesla CEO Elon Musk claimed in 2017 that Tesla was started in response to GM's cancellation of the EV1 program.[66]

Later GM EVs

Some of the deactivated EV1s given to universities and engineering schools were reactivated, and driven on public roads. The institutions came under fire from General Motors for violating the agreements of the donation, which indicated that the cars not be "titled, licensed, nor driven on public highways" and could only be restored and showcased.[67][68]

In 2004, General Motors donated one of the first generation EV1s (serial number 660) to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. As of December 2016, it is displayed as part of the "America on the Move" exhibit at the National Museum of American History.[69] This is the only existing EV1 not disabled, since the Smithsonian only accepts intact specimens.[12]

Within the framework of GM's vehicle electrification strategy,[70] and following the US market introduction of the Chevrolet Volt plug-in hybrid vehicle in late 2010, the Chevrolet Spark EV was released in June 2013 as the first all-electric passenger car marketed by General Motors in the U.S. since the EV1 was discontinued in 1999.[71]

Technology and design

.jpg)

The decades before the release of the Impact and the EV1 had seen little in the way of development on the electric car front. The Henney Kilowatt, which ended production in 1961, was the last time a feasible production electric car of any sort had been released; GM's own Electrovair and Electrovette of 1966 and 1976, respectively, never reached production, amounting to little more than conceptual electric conversion kits for the automaker's popular gasoline models. Technical and production costs difficulties were blamed.

In contrast to these cars, the EV1 was designed from the ground up to be an electric vehicle. It was not a conversion of an existing vehicle, nor did it share a drivetrain with another GM model, which contributed to its high development and production costs. The EV1 program was initially administered by a GM engineer named Kenneth Baker, who had been the lead on the Electrovette program in the 1970s.

Configuration

The EV1 was not only used to showcase the electric powertrain, but also premiered a number of features and technologies that would later find their way onto more common GM models and other manufacturers' cars. The EV1 was among the first production vehicles to utilize aluminum in the construction of the frame. The car's body panels were made of plastic rather than metal, making the car lightweight and dent resistant. The vehicle was fitted with Anti-lock brakes and a traction control system. Comfort improvements included a keyless entry and ignition system, a special one-way thermal glass for better heat rejection on sunny days, an automated tire pressure loss warning system, electric power steering, and a time-programmable HVAC system.

To boost efficiency, the EV1 possessed a very low drag coefficient of Cd=0.19 and a drag area of CdA=3.95 sq ft (0.367 m2).[5][72] Super-light magnesium alloy wheels and seats provided strength despite their low weight, and self-sealing, low-rolling resistance tires developed by Michelin rounded out the EV1's exceptional efficiency characteristics.

The EV1 was a subcompact car, with a 2-door coupé body style. Dimensions were 169.7 in (4,310 mm) in length, 69.5 in (1,770 mm) in width and 50.5 in (1,280 mm) in height.

Drivetrain

The car's 3-phase AC induction electric motor produced 137 brake horsepower (102 kW) at 7000 rpm. Like electric trains and all vehicles with an electric motor (and unlike a car powered by an internal combustion engine), the EV1 could deliver its full torque capacity throughout its power band, producing 110 pound-feet (149 newton-meters) of torque anywhere between 0 and 7000 rpm, allowing the omission of a manual or automatic gearbox. Power was delivered to the front wheels through a single-speed reduction integrated transmission.

Battery

The Gen I EV1 models, released in 1996, used lead-acid batteries, which weighed 1,175 lb (533 kg). The first batch of batteries were provided by GM's Delco Remy Division; these were rated at 53 amp-hours at 312 volts (16.5 kWh), and initially provided a range of 60 miles (97 km) per charge. The battery pack design, including the battery tray, electronic monitoring, safety disconnects, and crashworthiness, was utilized on all EV1 models and accommodated future (planned) energy storage products including NiMH and Lithium-ion. Gen II cars, released in 1999, used a new batch of lead-acid batteries provided by Panasonic, which now weighed 1,310 lb (594 kg);[73] some Gen I cars were retrofitted with this battery pack. The Japanese batteries were rated at 60 amp-hours at 312 volts (18.7 kWh), and increased the EV1's range to 100 miles (161 km). Soon after the rollout of the second generation cars, the originally intended nickel metal hydride (NiMH) "Ovonic" battery pack, which reduced the car's curb weight to 2,908 lb (1,319 kg) entered production; this pack was also retrofitted to earlier cars (both battery pack designs were led and invented by John E. Waters under the Delco Remy organization). The NiMH batteries, rated at 77 amp-hours at 343 volts (26.4 kWh), gave the cars a range of 160 miles (257 km) per charge, more than twice what the original Gen I cars could drive with.

It took the NiMH-equipped cars as much as eight hours to charge to full capacity (though an 80% charge could be achieved in between one and three hours). The Panasonic battery pack consisted of twenty-six 12 volt, 60 amp-hour lead-acid batteries holding 18.7 kWh (67 megajoules) of energy. The NiMH packs contained twenty-six 13.2 volt, 77 Ah nickel-metal hydride batteries which held 26.4 kWh (95 megajoules) of energy.[74]

Driving experience

The experience of driving an EV1 was unlike a conventional gasoline or diesel vehicle. The EV1's drag coefficient of Cd=0.19 was low compared to production cars of the time, though the EV1 was not a production car as it was available only through lease, and was never actually sold to the public,[72] while typical contemporary production cars had a drag coefficient in the range Cd=0.3–0.4. The EV1's clean shape meant it produced less wind noise at highway speeds, providing a more comfortable driving experience for its occupants. At lower speeds, and when stationary, the car produced little to no noise at all, save for a slight whine from the single-speed gear reduction unit. The car's smooth shape, waterfall tail and rear fender skirts gave it a distinctive appearance. The EV1 had no analog dials, and all instrumentation readouts were displayed in a single thin curved strip mounted high on the dashboard, just underneath the windshield.

Thanks to the on-demand torque output of the electric motor, the EV1 could accelerate from 0–50 mph (0–80 km/h) in 6.3 seconds, and from 0–60 mph (0–97 km/h) in eight seconds.[76] The car's top speed was electronically limited to 80 mph (129 km/h). At the time of release, the lead-acid battery-equipped EV1 was the only electric car produced which met all of the United States Department of Energy's EV America performance goals.[77]

The home charger provided by GM, which was required for "fast recharging" of the car, measured roughly 1.5 by 2 by 5 feet (0.45 x 0.60 x 1.50 m), and featured integrated heatsinks and a resemblance to a gasoline pump. The charger refueled the car using induction, accomplished by inserting a Magne Charge paddle into the slot between the EV1's headlights. The wireless charging technology meant that no direct connection was made, and charging the car while it was raining did not pose any risks, though there were isolated incidents involving fires starting at the charge port. GM also offered a 120 V AC convenience charger that could be used with any standard North America power socket to slow-charge the battery pack. The convenience charger was not available for EV1s equipped with the NiMH battery packs. Installation of the device took between one and two weeks, at an additional average cost of $2500.[78]

The EV-1 did not include a key to unlock and lock the vehicle, though one could be provided if the driver required one. To unlock or lock the car, drivers entered a personal identification number (PIN) on a keypad in the driver's side door, similar to that of Ford's Securicode system. Once inside, to start the car, no key was needed, nor was there a key slot. In the center console, there was a keypad on which the driver again entered the PIN to start the vehicle.

The EV-1 included the amenities comparable to other cars of the same era, such as an AM/FM car radio with a cassette player and a CD player, as well as an air conditioner and heater. The EV-1 seated two people.

Analysis of success vs. failure

The conventional business view of the EV1 as a failure is inherently controversial. If it is viewed as an attempt to produce a viable EV product, then it was a success, although certainly from GM's perspective the vehicle was not a commercial success, since the high profit margins typically seen with internal combustion engine vehicles remained elusive. However, if one considers the vehicle as a technological showpiece—a production electric car that actually could replace a gasoline powered vehicle—then the program's outcome is less definitive. The EV1 was produced for the consumer market, and many lessees found driving an EV1 to be a favorable experience.

Some analysts have suggested that it is inappropriate to compare the EV1 with existing gasoline powered commuter cars, since the EV1 was, in effect, a completely new product category that had no equivalent vehicles against which it might be judged.

Costs

GM based the lease payments for the EV1 on an initial vehicle price of US$33,995.[6] Lease payments ranged from around $299 to $574 per month, depending on the availability of state rebates. Since GM did not offer consumers the option to purchase at the end of the lease, the car's residual value was never established, making it impossible to determine the actual full purchase price or replacement value. One industry official said that each EV1 cost the company about US$80,000, including research, development and other associated costs;[79] other estimates placed the vehicle's actual cost as high as $100,000.[6] Bob Lutz, GM Vice Chairman responsible for the Chevrolet Volt, in November 2011 stated the EV1 cost $250,000 each and leased for just $300 per month.[80] GM stated the cost of the EV1 program at slightly less than $500 million before marketing costs, and over $1 billion in total, although a portion of this cost was defrayed by the Clinton Administration's $1.25 billion Partnership for a New Generation of Vehicles (PNGV) program.[81][82][83] In addition, all manufacturers seeking to produce electric cars for market consumption also benefited from matching government funds committed to the United States Advanced Battery Consortium.

Related development

General Motors revealed several prototype variants of the EV1 drivetrain at the 1998 Detroit Auto Show. The models included diesel/electric parallel hybrid, gas turbine/electric series hybrid, fuel cell/electric version and compressed natural gas low emission internal combustion engine version.[84] In addition, during this period, GM reorganized their electronics divisions (among them Hughes Electronics and Delco Divisions) into Delco Propulsion Systems in order to attempt to commercialize this technology in niche markets. Several non-affiliated companies purchased inverter and drivetrain systems from DPS for vehicle/fleet conversion purposes.

The new platform was a four-passenger variant of the EV1, lengthened by 19". This design was based on an internal (GM) program for a more "marketable" EV begun during the proof of concept phase of the EV1's development. During the original EV1 R&D period, focus groups indicated one of the major market limiting factors of the original EV1 was its two-seater configuration. GM investigated the possibility of making the EV1 a four-seater, but ultimately determined that the increased length and weight of the four seater would reduce vehicle's already limited range to 40–50 miles (64–80 km), placing the first ground-up electric car's performance squarely in the pack of aftermarket gas vehicle conversions. General Motors chose to produce the lighter, two-seat design.

For hybrid and electric vehicles, the battery pack was upgraded to 44 NiMH cells, arranged in "I" formation down the centerline, which could fully recharge in just 2 hours using onboard 220 V induction charger; additional power units were installed in the trunk, thus complementing the 3rd generation 137 hp AC Induction electric motor installed in the hood. Hybrid modifications retained the capability of all-electric ZEV propulsion for up to 40 miles (64 km).

EV1 CNG

The compressed natural gas (CNG) variant was the only non-electric vehicle in the line-up, even though it employed the same up-stretched platform. It used a modified Suzuki G10T 1.0 liter turbocharged 3-cylinder all-aluminum OHC engine installed under the hood. Due to the high octane rating of the CNG (allowing for a greater compression ratio), this small engine was able to deliver 72 bhp (54 kW) at 5500 rpm.

The batteries were replaced with two CNG tanks capable of maximum operating pressure of 3000 psi. The tanks could be refueled from a single nozzle in only 4 minutes. In-tank solenoids shut off the fuel during refueling and engine idle, and a pressure relief device safeguarded against excessive temperature and pressure. With the help of a continuously variable transmission, the car accelerated 0–60 mph (0–97 km/h) in 11 seconds. The maximum range was 350–400 miles (560–640 km), and fuel economy was 60 mpg‑US (4 l/100 km) in gasoline equivalent.

EV1 series hybrid

The series hybrid prototype had a gas turbine engine APU placed in the trunk. A single-stage, single-shaft, recuperated gas turbine unit with a high-speed permanent-magnet AC generator was provided by Williams International; it weighed 220 lb (100 kg), measured 20 in (51 cm) in diameter by 22 in (56 cm) long and was running between 100,000 and 140,000 rpm.[85] The turbine could run on a number of high-octane alternative fuels, from octane-boosted gasoline to compressed natural gas. The APU started automatically when the battery charge dropped below 40% and delivered 54 bhp (40 kW) of electrical power, sufficient to simultaneously sustain the EV1's 80 mph top speed whilst returning the car's 44 NiMH cells to (and maintain them at) a 50% charge level.

A fuel tank capacity of 6.5 US gal (24.6 L; 5.4 imp gal) and fuel economy of 60 mpg‑US (3.9 L/100 km; 72 mpg‑imp) to 100 mpg‑US (2.4 L/100 km; 120 mpg‑imp) in hybrid mode, depending on the driving conditions, allowed for a highway range of more than 390 mi (630 km). The car accelerated to 0–60 mph (0–97 km/h) in 9 seconds.

There was also a research program[86] that powered the series hybrid Gen2 version from a Stirling engine-based generator. The program demonstrated the technical feasibility of such a drive train, but it was concluded that commercial viability was out of reach at that time.

EV1 parallel hybrid

The parallel hybrid variant featured a de-stroked 1.3 L turbocharged DTI diesel engine (Isuzu Circle L), delivering 75 hp (56 kW), installed in the trunk along with an additional 6.5 hp (4.8 kW) DC motor/generator; the two motors drove the rear wheels through an electronically controlled transaxle. When combined with the AC induction motor which powered the front wheels, all three power units delivered a total output of 219 hp (163 kW), accelerating the car to 0–60 mph (0–97 km/h) in 7 seconds. A single tank of diesel fuel could keep the car running for 550 miles (890 km) with a fuel economy of 80 mpg‑US (2.9 L/100 km; 96 mpg‑imp).

A similar technology is used in the 2005 Opel Astra Diesel Hybrid concept.

EV1 fuel cell

This variant extended all-electric propulsion capabilities with a methanol-powered fuel cell system (developed by Daimler-Benz/Ballard for the Mercedes-Benz NECAR), again installed in the trunk. The system consisted of a fuel processor, an expander/compressor and the fuel cell stack. The highway range was about 300 miles (480 km), with a fuel economy of 80 mpg‑US (2.9 L/100 km; 96 mpg‑imp) (in a gasoline equivalent). The car accelerated to 0–60 mph (0–97 km/h) in 9 seconds.

Who Killed the Electric Car?

The demise of the EV1 is the subject of a 2006 documentary film entitled Who Killed the Electric Car?. Much of the film accounts for GM's efforts to demonstrate to California that there was no demand for their product and then to reclaim and dispose of every EV1 manufactured. A few vehicles were disabled and given to museums and universities, but almost all were found to have been crushed, or shredded using a special machine, as seen in the documentary.[87] However, apparently one or more EV1s did remain in private hands: director Francis Ford Coppola showed off his EV1 on "Jay Leno's Garage", though whether it is driveable is unclear.[88] One theory on why GM destroyed the cars discussed is that the EV1 program was eliminated because it threatened the oil industry.

GM responded to the film's claims, laying out several reasons why the EV1 was not commercially viable at the time and that the company had issues finding parts for the car.[89]

See also

- Henney Kilowatt The first effort by a large corporate entity to manufacture a "plug-in" electric car with range and speed suitable for commuter and highway use. Manufactured from 1959 - 1960

- Toyota RAV4 EV First Generation, a contemporary EV with similar range, NiMH battery capacity, inductive charging paddle standard, small production levels

- Cadillac ELR, a luxury plug-in hybrid car

- Chevrolet Spark EV, the first all-electric car sold by GM, produced since June 2013

- Chevrolet Bolt EV, an all-electric car that started production in 2017

- Chevrolet Volt, a plug in hybrid introduced in December 2010

- Voltec, the Chevy Volt powertrain and energy storage system[90]

- Chevrolet S-10 EV, a GM electric pickup truck that used EV1 technology.

- Honda EV Plus, another late 1990s electric car, vehicles were also destroyed by the manufacturer

- Tesla Roadster (2008)

- Nissan Leaf, the first battery-powered car to break 15,000 sales in the United States.

- Patent encumbrance of large automotive NiMH batteries

- Plug In America, an organization which campaigned to save electric cars such as the EV1 from being crushed.

- List of production battery electric vehicles

- Government incentives for plug-in electric vehicles

- List of modern production plug-in electric vehicles

- Plug-in electric vehicle

- GMC Hummer EV, GM's first production electric pickup truck available to the public, scheduled for release in late 2021.

References

- https://www.fueleconomy.gov/feg/Find.do?action=sbs&id=30968

- https://www.fueleconomy.gov/feg/Find.do?action=sbs&id=30969

- https://www.fueleconomy.gov/feg/comparempg.shtml#id=30968

- https://www.fueleconomy.gov/feg/comparempg.shtml#id=30969

- "1996 GM EV1-04". Archived from the original on 2015-11-18.

- Quiroga, Tony (August 2009). "Driving the Future". Car and Driver. Hachette Filipacchi Media U.S., Inc. p. 52.

- Adler, Alan L. (1996-09-29). "Electrifying Answers". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2013-10-28.

- "EV1 FAQ". Ev1-club.power.net. Archived from the original on 2007-08-18. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- 05/26/2008 (2008-05-26). "20 Truths About the GM EV1 Electric Car". GreenCar.com. Archived from the original on 2009-01-23. Retrieved 2009-07-22.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Witzenburg, Gary (2008-09-05). "At Witz' End: GM EV1 – The Real Story, Part III". Autobloggreen.com. Archived from the original on 2009-07-26. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- Taylor, Michael (2005-04-24). "Owners charged up over electric cars, but manufacturers have pulled the plug". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- Jim Motavalli (2013-07-03). "GM's EV1 Lives On, With EV2 on the Way". PluginCars.com. Retrieved 2013-07-03.

- Stevenson, Richard W. (4 January 1990). "G.M. Displays the Impact, An Advanced Electric Car". The New York Times.

General Motors had high hopes that the car could be the first to bridge the gap between limited-production electrical vehicles .. and mass-produced autos. "It is producable". most comfortable with 100,000 cars a year, not 20,000. "It's a total system approach" said John S. Zwerner, a top engineer at General Motors. "Every detail has been important."

- "GM EV1 and the Los Angeles City Council (53 items) | MacCready Papers". maccready.library.caltech.edu. 1996-01-22.

- GM Issue Update: Imagine the Impact (12min) (Promotional short). United States: General Motors. 1990.

- EV1 White Paper (2002-09-11), EV1 White Paper, archived from the original on 2009-07-26, retrieved 2009-07-21

- Horton, Peter (2003-07-08). "Peter Buys an Electric Car". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2020-01-31.

- "GM EV1 and the Los Angeles City Council (53 items) | MacCready Papers". maccready.library.caltech.edu. 1996-01-22.

- "GM EV1 and the Los Angeles City Council (53 items) | MacCready Papers". maccready.library.caltech.edu. 1996-01-22.

- Shnayerson, Michael (1996). The Car That Could. New York: Random House.

- "Electric Vehicles UK". Evuk.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- Wald, Matthew L. (1994-01-28). "Expecting a Fizzle, G.M. Puts Electric Car to Test". The New York Times. pp. Cover story.

- Shnayerson, Michael (1996). The Car That Could. New York: Random House. p. 182.

- "EV1 VIN Collection". Archived from the original on 2008-03-22.

- Dean, Paul; Reed, Mack (1996-12-06). "An Electric Start – Media, Billboards, Web Site Herald Launch of the EV1". Los Angeles Times.

- Truett, Richard (1997-06-26). "GM'S EV1 Blazes the Trail to Tomorrow". Orlando Sentinel. US. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- Fisher, Lawrence M. (5 January 1996). "G.M., in a First, Will Sell a Car Designed for Electric Power This Fall". The New York Times.

- Keith Naughton (1997-12-15). "Detroit: It Isn't Easy Going Green". Business Week. Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- Parrish, Michael (14 April 1994). "Trying to Pull the Plug : Big Oil Companies Sponsor Efforts to Curtail Electric, Natural Gas Cars". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020.

big oil companies have been largely silent. But now the companies have found their voice--or, more accurately, the voice of others--by quietly bankrolling what on its face appears to be a grass-roots campaign against $600 million in proposed utility investments in alternative-vehicle support systems. A new group called Californians Against Utility Company Abuse--run by Woodward & McDowell, a high-powered Burlingame, Calif.-based public relations firm--gathered petitions and demonstrated Wednesday in front of a regional office of Southern California Gas Co. The group also recently mailed a letter to 200,000 utility ratepayers statewide. It does not mention oil industry support in its literature.

- Chris Paine (2006). Who Killed The Electric Car? (Film). United States: Plinyminor.

- Kirsch, David A. (2000-03-06). "EV1 Recall: GM Fails to Learn from Its Own Success and Pulls the Plug on Drivers of the Future". EV World.

- Emily Thornton (1997-12-15). "JAPAN'S HYBRID CARS". Business Week. Archived from the original on 2011-06-28. Retrieved 2010-03-07.

- Moore, Bill (1999-09-17). "GM Remains Committed To Its Electric Cars: An Interview with Ken Stewart". EV World.

- Gellene, Denise (1998-05-22). "Electric Car Owner Spots GM Some Ads". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- "Gen II GM EV1 electric car". Kingoftheroad.net. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- "The Gen I EV1 Fire and Recall". Ka9q.net. 2000-02-17. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- "1997 Generation 1 EV1 Safety Recall". Archived from the original on 2008-04-20.

- "Who Killed the Electric Car: GM and Chevron". Ev1.org. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- Dr. F. Jameson, EV1 Timeline "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-12-16. Retrieved 2008-01-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "EV 1 Program and Lease Policy Changes, page 1 (letter sent to EV1 lessees)". Archived from the original on 2007-08-23.

- "EV 1 Program and Lease Policy Changes, page 2 (letter sent to EV1 lessees)". Archived from the original on 2007-08-23.

- "GM Recalls 900 Electric Cars, Trucks" (Press release). US: General Motors. 2000-03-02. Retrieved 2017-05-11 – via Phil Karn's EV Page.

- Karn, Phil. "The Gen I EV1 Fire and Recall". www.ka9q.net. Retrieved 2017-05-11.

- Mieszkowski, Katharine (2002-09-04). "Steal this car!". Salon. Salon Media Group. Archived from the original on 2019-06-18. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- "GM: Hybrids, Fuel Cells, and the Lawyers" (PDF). Convention and Tradeshow News. 2001-12-12. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-02-24.

Nowhere in this plan am I going out and taking cars off the road from customers,” he says, “without the customer requesting it first.

- Welch, David; Woellert, Lorraine. "The Eco-Cars". Business Week. Archived from the original on 2007-03-15. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- "Open House at RTC for GM's 100th Anniversary" (PDF). Mott Community College Chronicle (Sept): 28–28. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-01-26.

- Adams, Noel (2001-12-02). "Why is GM Crushing Their EV-1s?". Electrifying Times.

- Schneider, Greg; Edds, Kimberly (2005-03-10). "Fans of GM Electric Car Fight the Crusher". The Washington Post. US. Retrieved 2016-06-11.

- Healey, James R. (2000-06-02). "California May Soften Electric Car Mandate". USA Today. p. 3B.

- Moore, Bill (2000). "Do 10 Million Californians Want EVs? An Interview with Michael Coates". EV World.

- "The Current and Future Market for Electric Vehicles". Green Car Institute. 2000. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Amendments to the California Zero Emission Vehicle Program Regulations – Final Statement of Reasons" (PDF). State of California Environmental Protection Agency Air Resources Board. December 2001. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- "California's Auto Emissions Laws". PBS. 2005-04-15. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- Moore, Bill (2002-07-06). "California Injunction Blues". EV World. Archived from the original on 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2002-07-23.

- "Calif. Buckles on Zero Emissions". Reuters. 2003-08-12. Archived from the original on 2012-11-04. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- The Arizona Republic, 2005-03-15

- Adams, Noel (2001-12-02). "Why is GM Crushing Their EV-1s?". Electrifying Times. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- White, Joseph B. (2006-12-12). "GM, Toyota Bet Hybrid Green". Wall Street Journal.

The EV1 was a failure, as were other electric vehicles

- "The 50 Worst Cars of All Time". Time Magazine. 2008. Archived from the original on 2016-04-20. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- Motor Trend, June 2006, page 94

- Norris, Michele (2008-12-04). "GM CEO Outlines Company's Plans". NPR. US. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- Caryl, Christian; Kashiwagi, Akiko (2008-07-12). "Toyota is on track to pass General Motors this year as the world's No. 1 auto company. How GM plans to fight back". Newsweek International. Archived from the original on 2008-12-23. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- Evarts, Eric C. (2018-11-26). "GM to kill Chevy Volt production in 2019 (Updated)". Green Car Reports. US. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- Bihani, Shipra (2017-06-10). "Here's why Elon Musk started Tesla". Times of India. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

- "GM EV1 WWU Resurrection". Archived from the original on 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- "GM to HIT University up with Legal Action over EV-1 that Runs ?? Click to flag this post".

- National Museum of American History, Behring Center, in Washington, D.C.

- Brinkman, Norman; Eberle, Ulrich; Formanski, Volker; Grebe, Uwe-Dieter; Matthe, Roland (2012-04-15). "Vehicle Electrification - Quo Vadis". VDI. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- Jerry Garrett (2012-11-28). "2014 Chevrolet Spark EV: Worth the Extra Charge?". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- 20 Truths About the GM EV1 Electric Car, Greencar.com, 2008-05-26, archived from the original on 2009-01-23, retrieved 2009-07-18

- Mendoza, Alvaro; Argueta, Juan (April 2000). "Performance Characterization - GM EV1 Panasonic Lead Acid Battery" (PDF). South California Edison. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- "Plug-in Hybrids: What's the Big Deal? - GM Volt - Electric Car - ASPO USA". Archived from the original on 2012-11-03.

- "1998 GM EV1 2-DR. | Safercar – NHTSA". Safercar.gov. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- "Microsoft Word - ev1.doc" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-10-17. Retrieved 2010-10-20. Alt URL

- "Full Size Electric Vehicles". Avt.inel.gov. 2010-06-24. Archived from the original on 2005-04-06. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- "GM EV1". SeattleEVA. Archived from the original on 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- Schneider, Greg (2003-10-22). "The Electric-Car Slide". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- Rose, Charlie (2011-11-09). Interview of Bob Lutz about his book Car Guys vs. Bean Counters. The Battle for the Soul of American Business. Archived from the original on 2012-04-23. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- "CRS Report: 96-191 – The Partnership for a New Generation of Vehicles – NLE". Ncseonline.org. Archived from the original on 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- "Remarks by US President Bill Clinton at Clean Car Event". 1993-09-29. Archived from the original on 2001-07-26. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- "Office of Science and Technology Policy | The White House". Ostp.gov. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- Windbergs, Thor (1998). "Motoring into the New Millennium". Colorado Engineer Magazine. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- "General Motors EV1 picture and photo gallery and history". EV1 Museum. Archived from the original on 2013-02-24. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- Roland, Gravel. "The General Motors/HEV Is Targeted for Consumer Acceptance" (PDF). Office of Transportation Technologies. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

- "Could the electric car save us?". CBS News. 2007-09-06. Retrieved 2009-12-05.

- "The Cars of Tomorrow". CNBC. 2015-12-02. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- Barthmuss, Dave (2006-06-23). "Who Ignored the Facts About the Electric Car?" (PDF) (Press release). US: General Motors. Retrieved 2017-06-15 – via Alt Fuels.

- Matthe, Roland; Eberle, Ulrich (2014-01-01). "The Voltec System - Energy Storage and Electric Propulsion". Retrieved 2014-05-04.

Notes

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to General Motors EV1. |