Vladimir Korolenko

Vladimir Galaktionovich Korolenko (Russian: Влади́мир Галактио́нович Короле́нко, Ukrainian: Володи́мир Галактіо́нович Короле́нко, 27 July 1853 – 25 December 1921) was a Ukrainian-born Russian writer, journalist, human rights activist and humanitarian of Ukrainian and Polish origin. His best-known work include the short novel The Blind Musician (1886), as well as numerous short stories based upon his experience of exile in Siberia. Korolenko was a strong critic of the Tsarist regime and in his final years of the Bolsheviks.

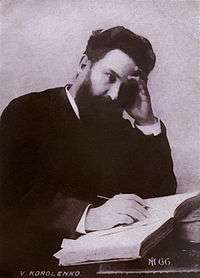

Vladimir Korolenko | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Ilya Repin | |

| Born | Vladimir Galaktionovich Korolenko 27 July 1853 Zhitomir, Volhynian Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 25 December 1921 (aged 68) Poltava, Ukrainian SSR |

| Signature |  |

Biography

Early life

Vladimir Korolenko was born in Zhytomyr, Ukraine (Volhynian Governorate), then part of the Russian Empire.[1] His Ukrainian Cossack father, Poltava-born Galaktion Afanasyevich Korolenko (1810-1868), was a district judge who, "amongst the people of his profession looked like a Don Quixote with his defiant honesty and refusal to take bribes", as his son later remembered.[2][3] His mother Evelina Skórewicz (1833-1903) was of Polish origin. In his early childhood Korolenko "did not very well know to which nationality he belonged and learned to read Polish before he did Russian," according to D.S. Mirsky. It was only after the 1863 January Uprising that the family did have to 'choose' its nationality and decided to 'become' Russians.[4] After the sudden death of her husband in Rovno in 1866, Evelina Iosifovna, suffering enormous hardships, somehow managed to raise her five children, three sons and two daughters, on a meagre income.[5]

Education and first exile

Korolenko started his education in a Polish Rykhlinsky boarding school to continue it in the Zhitomir and later Rovno gymnasiums, graduating the latter with silver medal.[3] In his final year, he discovered the works of Nikolai Nekrasov and Ivan Turgenev. "It was then that I found my true 'native land' and that was the world of, first and foremost, Russian literature," he later wrote. He also cited Taras Shevchenko and Ukrainian folklore as major influences.[2]

In 1871 Korolenko enrolled into Saint Petersburg Technological Institute but after a year spent in utmost poverty had to leave in early 1873 due to financial problems.[3] In 1874 he moved to Moscow and joined the Moscow College of Agriculture and Forestry. He was expelled from it in 1876 for having signed a collective letter protesting against the arrest of a fellow student, and was exiled to the Vologda region, then Kronstadt, where the authorities agreed to transfer him, answering his mother's plea.[2] In August 1877 Korolenko enrolled in the Saint Petersburg Mineral Resources Institute where he became an active member of a Narodnik group. Eight months later was reported on by a 3rd Section spy (whom he had exposed to friends), arrested and sent into exile, first to Vyatka, then Vyshnevolotsky District (where he spent six months in jail) and later Tomsk. He was finally allowed to settle in Perm.[2]

Literary career

Korolenko's debut short story, the semi-autobiographical "Episodes from the Life of a Searcher" telling the story of a young Narodnik desperately looking for his social and spiritual identity,[1] was published in the July 1879 issue of Saint Petersburg's Slovo magazine.[3] Another early story, "Chudnaya" (Чудная, Weird Girl), written in prison cell, spread across Russia in its hand-written form and was first published in London in 1893.[6]

In August 1881, while in Perm, Korolenko refused to swear allegiance to the new Russian Tsar Alexander III (the act that some political prisoners and exiles were demanded to perform, after the assassination of Alexander II) and was exiled again, this time much farther, to Yakutia.[3][7] He spent the next three years in Amga, a small settlement 275 versts from Yakutsk, where he did manual work, but also studied local customs and history. His impressions from his life in exile provided Korolenko with rich material for his writings, which he started to systematize upon arriving at Nizhny Novgorod, where in 1885 he was finally allowed to settle in.[3] In Nizhny, Korolenko became the center of the local social activism, attracting radicals to fight all kinds of wrongdoing committed by the authorities, according to the biographer Semyon Vengerov.[5]

"Makar's Dream" (Сон Макара) established his reputation as a writer when it was published in 1885.[6] The story, based on a dying peasant's dream of heaven, was translated and published in English in 1892. This, as well as numerous other stories, including "In Bad Company" (В дурном обществе, better known in Russia in its abridged version for children called "Children of the Underground"), and "The Wood Murmurs" (Лес шумит),[8] comprised his first collection Sketches and Stories (Очерки и рассказы), which, featuring pieces from both the Ukrainian and Siberian cycles, came out in the late 1886.[2] Also in 1886 he published the short novel Slepoi Muzykant (Слепой музыкант),[8] which enjoyed 15 re-issues during its author's lifetime. It was published in English as The Blind Musician in 1896-1898.[3]

Korolenko's second collection, Sketches and Stories (1893) saw his Siberian cycle continued ("At-Davan", "Marusya's Plot"), but also featured stories ("Following the Icon" and "The Eclipse", both 1887; "Pavlovsk Sketches" and "In Deserted Places", both 1890) inspired by his travels throughout Volga and Vetluga regions that he had made while living in Nizhny. One of his Siberian stories, "Sokolinets" was praised by Anton Chekhov, who in a 9 January 1888 letter called it "the most outstanding [short story] of the latest times" and likened it to perfect musical composition.[6][9] After visiting the Chicago exhibition during 1893 as a correspondent for Russkoye Bogatstvo, Korolenko wrote the novella "Bez yazyka" (Без языка, Without Language, 1895) telling the story of an uneducated Ukrainian peasant, struggling in America, unable to speak a word in English.[7][10]

In 1896 Korolenko moved his family to Saint Petersburg. Suffering from some stress-induced psychological disorders, including insomnia, in September 1900 he returned to Poltava. There he experienced a bout of creativity and, having finished his Siberian short story cycle, published his third volume of Sketches and Stories in 1903.[3] By this time Korolenko was well established amongst Russian writers. He was a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences but resigned in 1902 when Maxim Gorky was expelled as a member because of his revolutionary activities. (Anton Chekhov resigned from the Academy for the same reason).[3]

In the autumn of 1905 he started working upon the extensive autobiography The History of my Contemporary (История моего современника), fashioned to some extent after Alexander Hertzen's My Past and Thoughts.[4] Part one of it was published in 1910, the rest (Part 4 unfinished) came out posthumously, in 1922. In 1914 the Complete Works by V.G. Korolenko came out.[1]

Career as a journalist

Starting from 1887, Korolenko became actively involved with Severny Vestnik. In 1894, he joined the staff of Russkoye Bogatstvo (the magazine he stayed with until 1918) where he discovered and encouraged, among others, the young Alexey Peshkov (as he was still known in 1889) and Konstantin Balmont. "Korolenko was the first to explain to me the significance of form and the phrase structuring, and, totally surprised by how simply and clearly he managed to do this, for the first time did I realize that being a writer was not an easy job," Maxim Gorky remembered later, in the essay "The Times of Korolenko".[11]

Korolenko used his position in Russkoe Bogatstvo to criticise injustice occurring under the Tsar, as well as to publish reviews of important pieces of literature such as Chekhov's final play The Cherry Orchard in 1904.

Activism and human rights

Throughout his writing career Korolenko advocated for human rights and against injustices and persecutions. Considering himself 'only a part-time-writer', as he put it, he became famous as a publicist who, never restricting himself to mere journalistic work, was continually and most effectively engaged in the practical issues he saw as demanding immediate public attention.

In 1891-1892, when famine struck several regions of Central Russia, he went to work on the ground, taking part in the relief missions, collecting donations, supervising the process of delivering and distributing food, opening free canteens (forty five, in all), all the while sending to Moskovskiye Vedomosti regular reports which would be later compiled in the book V golodny god (В голодный год, In the Year of Famine, 1893) in which he provided the full account of the horrors that he witnessed, as well as the political analysis of the reasons of the crisis.[12]

In 1895-1896 he spent enormous amount of time supervising the court case of the group of the Udmurt peasants from Stary Multan village who were falsely accused of committing ritual murders. Writing continuously for numerous Russian papers (and in 1896 summarizing his experiences in "The Multanskoye Affair", Мултанское дело) Korolenko made sure the whole country became aware of the trial, exposed the fabrications, himself performed as barrister in court and almost single-handedly brought about the acquittal, thus "practically saving the whole little nation from the horrible stain which would have remained for years should the guilty verdict have been passed," according to the biographer.[2] Stary Multan has been subsequently renamed Korolenko village, in his honour and memory.[13]

"The House No.13", his historic description of the Kishinev Pogrom of 1903, was banned by the Russian censorship and appeared in print in 1905 for the first time. It was also published in English.[13] As the 1905 Revolution started, Korolenko made a stand against the Black Hundred in Poltava. Numerous death threats he received by post have warranted the workers' picket guard to be put by his flat.[2]

In 1905 Russkoye Bogatstvo (which he had started editing a year earlier) published the Manifest by the Petersburg Soviet of the Workers' deputies. As its editor-in-chief, Korolenko was repeatedly sued by the authorities, had his flat raided by the police and the materials deemed subversive confiscated.[3]

Starting in 1906, he headed the campaign against military law and capital punishment and in the late 1900s sharply criticised the governments' punitive actions ("Everyday Phenomenon", 1910, "Features of Military Justice", 1910, "In the Pacified Village", 1911).[4] Of "Everyday Phenomenon" Leo Tolstoy wrote: "It ought to be re-printed and published in million copies. None of the speeches in Duma, or treatises, or dramas or novels would have one thousandth of the benign effect this article should have". [14] Foreworded by Tolstoy, it was published abroad in Russian, Bulgarian, German, French and Italian languages.[13]

In 1913 he took strong public stand against the anti-Semitic Beilis trial and wrote the powerful essay "Call to the Russian People in regard to the blood libel of the Jews" (1911–13).[7][13] Korolenko never belonged to any political party, but ideologically was close to the Popular Socialists. None of the two extremes of the famous 'Stolypin dylemma' attracted him, "he fancied neither 'great tribulations' in terms of 1918, nor the 'Great Russia' as of its 1914 model," according to Mark Aldanov.[15]

Last years

Vladimir Korolenko, who was a lifetime opponent of Tsarism and described himself as a "party-less Socialist", reservedly welcomed the Russian Revolution of 1917 which he considered to be a logical result of the whole historical course of things. However, he soon started to criticize the Bolsheviks as the despotic nature of their rule became evident. During the Russian Civil War that ensued, he condemned both Red Terror and White Terror.[7] While in Poltava in the years of the Civil War, risking his life, Korolenko pleaded against atrocities, of which there were many from all sides of the conflict. While trying to save from death the Bolsheviks arrested by the 'whites', he appealed for the 'reds' against reciprocating with terror, arguing (in his letters to Anatoly Lunacharsky) that the process of "moving towards Socialism should be based upon the better sides of the human nature." [2] Up until his dying day, suffering from a progressive heart disorder, he was busy collecting food packages for children in famine-stricken Moscow and Petrograd, took part in organizing orphanages and shelters for the homeless. He was elected the honourable member of the Save the Children League, and the All-Russia Committee for Helping the Famine Victims.[2]

Vladimir Korolenko died in Poltava, Ukraine, of the complications of pneumonia on 25 December 1921.[3]

Family

Vladimir Korolenko had two brothers and two sisters. His third sister Alexandra died in 1867, aged 1 year and 10 months, and was buried in Rovno.[16]

Yulian Korolenko (born 16 February 1851, died 15 November 1904) in the 1870s worked as a proofreader in Saint Petersburg. As a narodnik circle's member, he was arrested in 1879 and spent short time in jail. Later in Moscow he joined the staff of Russkye Vedomiosti newspaper and contributed to its Moscow Chronicles sections. In his early life Yulian was interested in literature, wrote poetry and co-authored (with Vladimir) the translation of "L'Oiseau" by Jules Michelet, published in 1878 and signed, collectively, "Коr-о".[16]

Illarion Korolenko (21 October 1854 - 25 November 1915), also a Narodnik activist, was sent into exile in 1879 and spent five years in Glazov, Vyatka Governorate where he worked as a locksmith in a small workshop he co-owned with a friend. Later, residing in Nizhny and working as an insurance company inspector, he travelled a lot and, having met in Astrakhan Nikolai Chernyshevsky, became instrumental in both authors' meeting. He is portrayed in two of Korolenko's autobiographical stories, "At Night" (Ночью) and "Paradox" (Парадокс).[16]

Maria Korolenko (7 October 1856 - 8 April 1917) graduated the Moscow Ekaterininsky Institute and worked as a midwife. She married the Military Surguical Academy student Nikolai Loshkaryov and in 1879 followed him into exile to Krasnoyarsk. Upon the return both lived in Nizhny Novgorod.

Evelina Korolenko (20 January 1861 - September 1905), graduated the midwife courses in Petersburg, and later worked as a proofreader.[16]

In January 1886 Vladimir Korolenko married Evdokiya Semyonovna Ivanovskaya (Евдокия Семёновна Ивановская, born 1855, Tula Governorate; 1940 in Poltava), a fellow Narodnik he first met years ago in Moscow. She was arrested twice, in 1876 and 1879, and spent 1879-1883 in exile before being allowed to settle in Nizhny Novgorod where she met and married her old friend Korolenko. In this marriage, described as very happy and fulfilling, two daughters, Natalya and Sophia, were born (two more died in infancy).[16]

Natalya Lyakhovich-Korolenko (1888—1950) was a philologist and literary historian, who edited some of the post-1921 editions of her father's books. Her husband Konstantin Ivanovich Lyakhovich (1885—1921) was a Russian Social Democrat, the leader of the Poltava's Mensheviks in 1917-1921.[17]

Sofia Korolenko (1886—1957) worked for several years as a school teacher in rural area, then in 1905 became her father's personal secretary and was one of co-editors of the 1914 A.F. Marks' edition of the Complete Korolenko. Following her father's death Sofia Vladimirovna initiated the foundation of the Korolenko Museum in Poltava, of which for many years she has been the director. Her Book on My Father (Книга об отце, 1966-1968, posthumously) is a biography taken up exactly where his own The History of My Contemporary left of, in 1885 when, having just returned from exile, he settled in Nizhny Novgorod.[18]

Assessment and legacy

D.S. Mirsky considered Korolenko to be "undeniably the most attractive representative of the idealist radicalism in Russian literature." "Should it not be for Chekhov, he would have been the first among the writers and poets of his time," the critic argued. The important part of Korolenko's artistic palette was his "wonderful humor... often intertwined with poetry," according to Mirsky. "Completely devoid of the intricacies that usually come with the satire, it is natural, unforceful and has this levity which is rarely met with Russian authors," the critic opined. For Mirsky, Korolenko's style and language, full of "emotional poeticism and Turgenevesque pictures of nature," was "typical for what in the 1880s-1890s was considered to be 'artistry' in Russian literature." [4]

According to Semyon Vengerov, Korolenko had a lot in common with the Polish writers like Henryk Sienkiewicz, Eliza Orzeszkowa and Bolesław Prus, but still mastered his own style of prose in which "the best sides of the two literatures merged harmoniously, the colourful romanticism of the Poles, the poetic soulfulness of Ukrainian and Russian writers."[5] Numerous critics, Mirsky and Vengerov included, praised the author for ingenious depictions of the Northern Russia's nature[4] as well as vivid portrayal of the ways of the locals "in all their disturbing detail," as well as some "unforgettable human portraits of great psychological depth" (Vengerov).[5]

Mark Aldanov also saw Korolenko as belonging to the Polish school of literature, while owing a lot to the early Nikolai Gogol ("some of his stories would have fitted fine into the Dikanka Evenings cycle"), who all the while happened to be "totally untouched by" neither Lev Tolstoy, nor Chekhov.[15]

The critic and historian Natalya Shakhovskaya considered Korolenko's most distinct feature to be "the way romanticism and harsh realism gelled both in his prose and his own character."[19] For the Soviet biographer V.B. Katayev, Korolenko was "a realist continually gravitating towards the romantic side of life" who has "walked his life the hard way of a hero."[20]

Writing in 1921, Anatoly Lunacharsky declared Korolenko "undoubtedly the biggest contemporary Russian writer" even if belonging wholly to the Russian historical and literary past, a "shining figure looming large between the liberal idealists and revolutionary narodniks."[21] Like many others he too chose 'humanism' as the most striking feature of Korolenko's legacy and argued that "in all our literature, so marked with humanism there has never been a more vivid proponent of the latter." Seeing the whole Russian literature as divided into two distinct sections, the one that tended towards simplicity (Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy) and another that went for "the musical quality, for outward perfection (Pushkin, Turgenev)", Lunacharsky placed Korolenko firmly into the latter camp and praised him for having "...enriched the Russian literature with true gems, one of the best in the Russian canon."[21]

Social activism

The majority of the critics, regardless of which political camp they belonged to, saw Korolenko the social activist at least as important and influential as Korolenko the writer. In his 1922 tribute Lev Gumilevsky, lauding the writer's style for "striking simplicity which added to the power of his word," called him Russia's "social... and literary conscience."[22] Mark Aldanov also considered him "the symbol of civil consciousness and lofty ideals in literature."[15]

The Soviet biographer F.Kuleshov praised Korolenko as "the defender of the oppressed" and a "truth-seeker, ardent and riotous, who with the fervency of a true revolutionary fought the centuries-long traditions of lawlessness."[23] According to this critic, the writer's unique persona united in itself "a brilliant story-teller..., astute psychologist, great publicist, energetic, tireless social activist, a true patriot and very simple, open and modest man with crystal clear, honest soul."[23] Maxim Gorky, while crediting Korolenko with being a "huge master and fine stylist," also opined that he did a lot to "awaken the sleeping social self-awareness of the majority of Russian nation".[23]

S. Poltavsky, calling his 1922 essay the "Quiet Hurricane", defined Korolenko as "the knight of the high image of Justice" who conducted his 'tournaments' with 'quiet humaine gentleness'.[24] Semyon Vengerov called Korolenko "a humanist in the most straightforward sense of the word" whose sincerity was so overwhelming as to "win [people] over no matter which political camp they belonged." "The high position Korolenko occupies in our contemporary literature is in equal degree the result of his fine, both humane and elegant literary gift, and the fact that he was "the 'knight of quill' in the best sense of the word," Vengerov wrote in 1911.[5]

"His life was the continuation of his literature and vice versa. Korolenko was honest. Things that he wrote and things that he did have merged into harmonic oneness for a Russian reader," the Modernist critic Yuly Aykhenvald wrote, looking for an answer as to why was Korolenko so "deeply, so profoundly loved in his lifetime by people belonging to different classes and groups."[25] Lauding Korolenko for being "Russia's pre-1905 one-man constitution," and the one who "just could not pass by without responding to any serious wrong-doing or social injustice," the critic noted: "He meddled with lots of things and those who disliked that were tempted to liken him to Don Quixote, but valiance was not just one single virtue of our Russian knight, for he was also highly reasonable and never spared his fighting powers for naught."[25]

Korolenko and revolution

The early Soviet critic Pavel Kogan argued that Korolenko was in a way contradicting himself by denouncing the revolutionary terror for it was him who had collected "the immense set of documents damning the Tsarist regime" which completely justified the cruelties of the Bolsheviks.[26] According to Kogan, there is hardly anything more powerful [in Russian journalism] than Korolenko's articles denouncing the political and religious violence of the old regime. "His works on the Beilis and the Multan affairs, the Pogroms of the Jews amounted to the journalistic heroism," the critic argued.[26] Korolenko, much in the way of Rousseau, whom Kogan saw him as being an heir to, "refused to follow the revolution, but he's been always within it, and this way, the part of it."[26]

All the while, many Russian authors in emigration expressed disgust at what they saw as the hypocrisy of the Bolsheviks who hastened to appropriate Korolenko's legacy for their propagandistic purposes. Mark Aldanov, for one, declared the excessive flow of official 'tributes', including the Lunacharsky's obituary, Demyan Bedny's poetic dedication and Grigory Zinoviev's speech a collective act of abuse, "desecrating his pure grave."[15]

Criticism

Mark Aldanov, who considered Korolenko the founder of his own new school of literature, a 'fine landscape painter' and in this respect a precursor to Ivan Bunin, was still ambivalent about Korolenko's literary legacy as a whole, describing him as an "uneven writer who authored some true masterpieces alongside dismally weak stories, one of his most famous ones, 'Chyudnaya', among them."[15]

While praising his style of writing, "devoid of modernist ornamentations," as well as "very simple, seemingly ordinary spoken language almost completely free from the hackneyed jargon of intelligentsia," Aldanov argued: "He was too gentle a man, who admired and respected the people too much to grow into a great writer," noting: "his stories are full of thieves, gamblers and murderers, with not a single evil man among them."[15]

Aykhenvald who lauded Korolenko's role as a purveyor of humanism in Russia, was less complimentary to his stories which he found, 'overcrowded', lacking in space. "There is no cosmos, no air, in fact, almost nothing except for lots and lots of people, all worried by their worldly problems, totally foreign to the notion of their mysterious unity with the great Universe," argued the critic, who described Korolenko's literary world as 'confined quartes' where 'horizons [were] narrow and well outlined' and everything was "portrayed in vague and simple lines."[25]

In fact, the author's humanism as such is "overbearing and in the end feels as if [the author] tries to exert some kind of violence over the reader's free will," according to the biographer. For Aychenvald, Korolenko is too "rational when observing human suffering; apparently seeing rational reasons behind it, he is invariably convinced that there must be some panacea for it, which will bring all pain to the end." For all his shortcomings, though, Korolenko, according to Aykhenvald, "remains one of the most attractive figures in the contemporary Russian literature," quick to enchant the reader with "his touchingly soft romanticism and tender melancholy gently lightening a dim world where misguided, orphaned souls and charming images of children roam."[25]

Ongoing influence

Korolenko is generally considered to be a major Russian writer of the late 19th century and early 20th century. Russian singer and literature student Pavel Lion (now Ph.D.) adopted his stage name Psoy Korolenko due to his admiration of Korolenko's work.

A minor planet 3835 Korolenko, discovered by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh in 1977 is named for him.[27]

Selected works

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Vladimir Korolenko |

- Son Makara (1885) translated as Makar's Dream (1891);

- Slepoi Muzykant (1886) translated as The Blind Musician (1896–1898);

- V durnom obshchestve (1885) translated as In Bad Company (1916);

- Les Shumit translated as The Murmuring Forest (1916);

- Reka igraet (1892) The River Sparkles;

- Za Ikonoi After the Icon

- Bez Yazyka (1895) or Without Language;

- Mgnovenie (1900) or Blink of an Eye;

- Siberian Tales 1901;

- Istoria moego sovremmenika or The History of My Contemporary an autobiography (1905–1921)

- Тени (1890) or The Shades, translated by Thomas Seltzer, available through Project Gutenberg

Quotes

- "Человек создан для счастья, как птица для полета, только счастье не всегда создано для него." (Human beings are to happiness like birds are to flight, but happiness is not always for them.) (Paradox)

- "Насилие питается покорностью, как огонь соломой." (Violence feeds on submission like fire feeds on dry grass.) (Story about Flora, Agrippina and Menachem)[28]

- "Лучше даже злоупотребления свободой, чем ее отсутствие." (It is better to abuse freedom than to have none.)

Footnotes

- ^ Korolenko's articles and Call to the Russian People in regard to the Beilis Trial

References

- Tyunkin, K.I. Foreword. The Works by V.G. Korolenko in 6 volumes. Pravda Publishers. Ogonyok Library. Moscow, 1971. Vol. 1, pp. 3-38

- Katayev, V.B. (1990). "Короленко, Владимир Галактионович". Russian Writers, Biobibliographical Dictionary. Vol. 1. Prosveshchenye, Moscow. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- "Korolenko Timeline // Основные даты жизни и творчества". The Selected Works by V.G. Korolenko. Prosveshchenye, Moscow. 1987. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Mirsky, D.S. Korolenko. The History of Russian Literature from Ancient Times to 1925 // Мирский Д. С. Короленко // Мирский Д. С. История русской литературы с древнейших времен до 1925 года / Пер. с англ. Р. Зерновой. London: Overseas Publications Interchange Ltd, 1992. - С. 533-537.

- Vengerov, Semyon. Короленко, Владимир Галактионович at the Russian Biographical Dictionary.

- Selivanova, S. Commentaries. The Works by V.G. Korolenko in 6 volumes. Vol 1. Pp. 481-493

- Steve Shelokhonov. Vladimir Galaktionovich Korolenko. - Biography at www.imdb.com

- Selivanova, S. Commentaries. The Works by V.G. Korolenko in 6 volumes. Vol 3. Pp. 325-333

- The letters by Anton Chekhov. Vol.2, pp. 170-171 //Чехов А. П. Полн. собр. соч. и писем: В 30 т. Письма. - М., 1975. Т. II. С. 170--171

- Selivanova, S., Tyunkin, K. Commentaries. The Works by V.G. Korolenko in 6 volumes. Vol 6. Pp. 383-397

- The Works by V.G. Korolenko in 20 volumes. Vol. 18, P. 157 // Собр. соч.: В 20 т. - М., 1963. - Т. 18. - С. 157

- Grikhin, V. Commentaries. The Works by V.G. Korolenko in 6 volumes. Vol 4. Pp. 509-525

- Tyunkin, K. Commentaries. The Works by V.G. Korolenko in 6 volumes. Vol 6. Pp. 396-419

- Lev Tolstoy's Correspondence. Vol.2, P.420 // Л. Н. Толстой. Переписка с русскими писателями: В 2 т.-- М., 1978.-- Т. 2.-- С. 420.

- В.Г. Короленко by Mark Aldanov

- Korolenko, S.V. The Commentaries to История моего современника. The History of My Contemporary. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura. 1954

- Ляхович Константин Иванович. Biography at Russian National Philosophy.-- hrono.ru

- Книга об отце by Sofya Korolenko. Udmurtia Publishers, Izhevsk. 1968

- http://az.lib.ru/s/shahowskajashik_n_d/text_1912_korolenko_oldorfo.shtml B. Г. Короленко. Опытъ біографической характеристики. Кн--во К. Ф. Некрасова/ МОСКВА 1912.

- Katayev, V.B. Moments of Heroism // Мгновения героизма. В.Г.Короленко. "Избранное" Издательство "Просвещение", Москва, 1987

- Lunacharsky, Anatoly Obituary. Луначарский, А. "Правда", 1921, No 294, 29 декабря

- Gumilevsky, Lev Korolenko's Literary Testament // Лев Гумилевский. "Культура", No 1, 1922 Литературный завет В. Г. Короленко.

- Kuleshov, F. I. Korolenko: The Riotous Talent // Мятежный талант В.Г. Короленко. / Избранное. Издательство "Вышэйшая школа", Минск, 1984

- Poltavsky, S. Quiet Hurricane. In the memory of V.G. Korolenko // Тихий ураган. Памяти В. Г. Короленко. Культура, No 1, 1922

- Aykhenvald, Yuly. Короленко // Короленко. Из книги: Силуэты русских писателей. В 3 выпусках.

- Kogan, P. S. In the Memory of V.G. Korolenko. Коган П.С. Памяти В.Г. Короленко. [Статья] // Красная новь. 1922. N 1. С. 238-243

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 325. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

- Ãàçåòà "Ïðèáîé" ã. Ãåëåíäæèê at www.coast.ru

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vladimir Korolenko. |

- Answers.com resources on Korolenko

- Student Encyclopedia article

- The 2-Hryvna coin dedicated to Korolenko (National Bank of Ukraine)

- Life of Korolenko by Rosa Luxemburg

- Vladimir Galaktionovich Korolenko, 1853-1921 Published in Reference Guide to Russian Literature (1998)

- Works by Vladimir Korolenko at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Vladimir Korolenko at Internet Archive

- Works by Vladimir Korolenko at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- In Russian