Vilayet

A vilayet (Turkish pronunciation: [vilaːˈjet]; French: vilaïet or vilayet[note 1]) was a first-order administrative division, or province of the later Ottoman Empire, introduced with the promulgation of the Vilayet Law (Turkish: Teşkil-i Vilayet Nizamnamesi) of 21 January 1867.[3] The reform was part of the ongoing administrative reforms that were being enacted throughout the empire, and enshrined in the Imperial Edict of 1856. The reform was at first implemented experimentally in the Danube Vilayet, specially formed in 1864 and headed by the leading reformist Midhat Pasha. The reform was gradually implemented, and not until 1884 was it applied to the entirety of the Empire's provinces.[3]

Etymology

The term vilayet is derived from the Arabic word wilayah or wilaya (ولاية). While in Arabic, the word wilaya is used to denote a province or region or district without any specific administrative connotation, the Ottomans used it to denote a specific administrative division.[4]

Administrative division

The Ottoman Empire had already begun to modernize its administration and regularize its provinces (eyalets) in the 1840s,[5] but the Vilayet Law extended this to the entire Ottoman territory, with a regularized hierarchy of administrative units: the vilayet, headed by a vali, was subdivided into sub-provinces (sanjak or liva) under a mütesarrif, further into districts (kaza ) under a kaimakam, and into communes (nahiye) under a müdir.[3]

The vali was the representative of the Sultan in the vilayet and hence the supreme head of the administration. He was assisted by secretaries in charge of finances (defterdar), correspondence and archives (mektubci), dealings with foreigners, public works, agriculture and commerce, nominated by the respective ministers. Along with the chief justice (mufettiş-i hukkam-i Şeri'a), these officials formed the vilayet's executive council. In addition, there was an elected provincial council of four members, two Muslims and two non-Muslims. The governor of the chief sanjak (merkez sanjak), where the vilayet's capital was located, deputized for the vali in the latter's absence. A similar structure was replicated in the lower hierarchical levels, with executive and advisory councils drawn from the local administrators and—following long-established practice—the heads of the various local religious communities.[6]

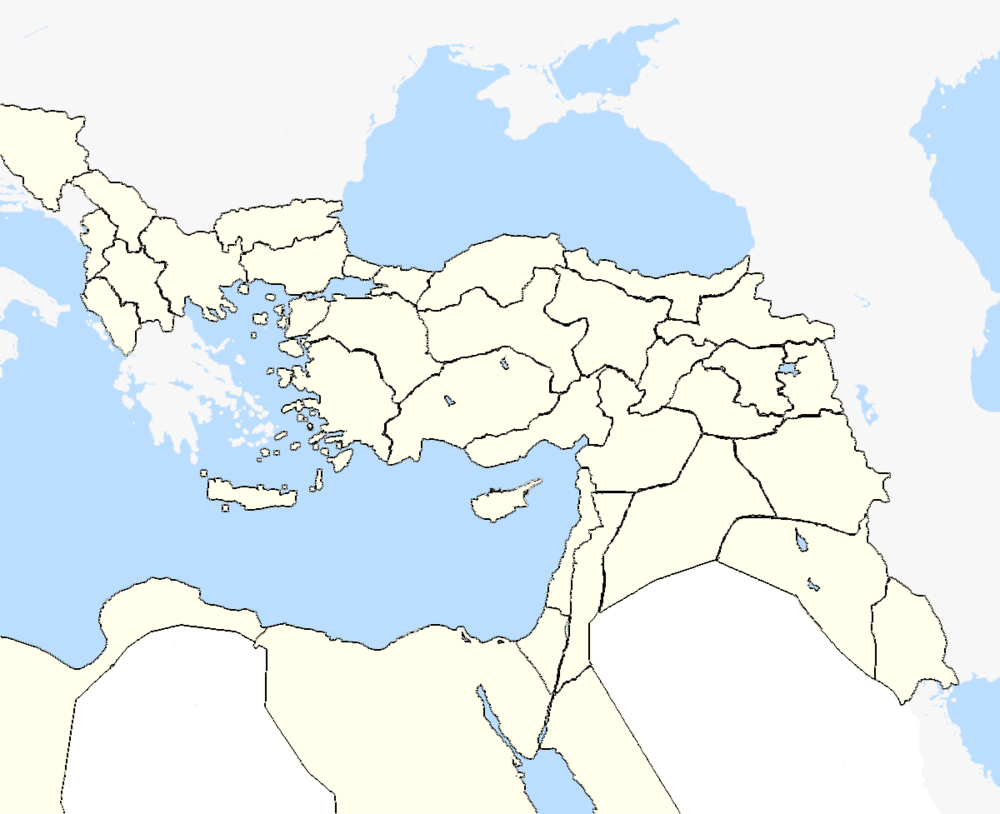

Map

Vilayets of the Ottoman Empire circa 1900:

List

Vilayets, sanjaks and autonomies, c. 1876

Vilayets, sanjaks and autonomies, circa 1876:[7]

- Vilayet of Constantinople

- Vilayet of Adrianople: sanjaks of Adrianople (Edirne), Tekirdağ, Gelibolu, Filibe, Sliven.

- Vilayet of the Danube: sanjaks of Ruse, Varna, Vidin, Tulcea, Turnovo, Sofia, Niš.

- Vilayet of Bosnia: sanjaks of Bosna-Serai, Zvornik, Banja Luka, Travnik, Bebkèh, Novi Pazar.

- Vilayet of Herzegovina: sanjaks of Mostar, Gacko.

- Vilayet of Salonica: sanjaks of Salonica, Serres, Drama.

- Vilayet of Ioannina: sanjaks of Ioannina, Tirhala, Ohrid, Preveze, Berat.

- Vilayet of Monastir: sanjaks of Manastir (now Bitola), Prizren, Üsküb, Dibra.

- Vilayet of Scutari: sanjak of Scutari.

- Vilayet of the Archipelago: sanjaks of Rhodes, Midilli, Sakız, Kos, Cyprus.

- Vilayet of Crete: sanjaks of Chania, Rethymno, Candia, Sfakia, Lasithi.

- Vilayet of Hudavendigar: sanjaks of Bursa, Izmid, Karasi, Karahisar-i-Sarip, Kütahya.

- Vilayet of Aidin: sanjaks of Smyrna (now İzmir), Aydın, Saruhan, Menteşe.

- Vilayet of Angora: sanjaks of Angora (now Ankara), Yozgat, Kayseri, Kırşehir.

- Vilayet of Konya: sanjaks of Konya, Teke, Hamid, Niğde, Burdur.

- Vilayet of Kastamonu: sanjaks of Kastamonu, Boli, Sinop, Çankırı.

- Kosovo Vilayet

- Vilayet of Trebizond: sanjaks of Trebizond (Trabzon), Gümüşhane, Batumi, Canik.

- Vilayet of Sivas: sanjaks of Sivas, Amasya, Karahisar-ı Şarki.

- Vilayet of Erzurum: sanjaks of Erzurum, Tchaldir, Bayezit, Kars, Mouch, Erzincan, Van.

- Vilayet of Diyarbekir: sanjaks of Diyarbakır, Mamuret-ul-Aziz, Mardin, Siirt, Malatya.

- Vilayet of Adana: sanjaks of Adana, Kozan, İçel, Paias.

- Vilayet of Syria: sanjaks of Damascus, Hama, Beirut, Tripoli, Hauran, Akka, Belka, Kudus-i-Cherif (Jerusalem).

- Vilayet of Aleppo: sanjaks of Aleppo, Maraş, Urfa, Zor.

- Vilayet of Baghdad: sanjaks of Baghdad, Mosul, Sharazor, Sulaymaniyah, Dialim, Kerbela, Helleh, Amara.

- Vilayet of Basra: sanjaks of Basra, Muntafiq, Najd, Hejaz.

- Emirate of Mecca: Mecca, Medina.

- Vilayet of Yemen: sanjaks of Sana'a, Hudaydah, Asir, Ta'izz.

- Vilayet of Tripolitania: sanjaks of Tripoli, Bengazi, Khoms, Djebal gharbiyeh, Fezzan.

- Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate

- Principality of Samos

- Mount Athos (part of the Sanjak of Salonica)

Vilayets and independent sanjaks in 1917

Vilayets and independent sanjaks in 1917:[8]

Vilayets

|

Independent Sanjaks

|

Vassals and autonomies

- Eastern Rumelia (Rumeli-i Şarkî): autonomous province (Vilayet in Turkish) (1878–1885); unified with Bulgaria in 1885

- Sanjak of Benghazi (Bingazi Sancağı): autonomous sanjak. Formerly in the vilayet of Tripoli, but after 1875 dependent directly on the ministry of the interior at Constantinople.[9]

- Sanjak of Biga (Biga Sancağı) (also called Kale-i Sultaniye) (autonomous sanjak, not a vilayet)

- Sanjak of Çatalca (Çatalca Sancağı) (autonomous sanjak, not a vilayet)

- Cyprus (Kıbrıs) (island with special status) (Kıbrıs Adası)

- Khedivate of Egypt (Mısır) (autonomous khedivate, not a vilayet) (Mısır Hidivliği)

- Sanjak of Izmit (İzmid Sancağı) (autonomous sanjak, not a vilayet)

- Mutasarrifyya/Sanjak of Jerusalem (Kudüs-i Şerif Mutasarrıflığı): independent and directly linked to the Minister of the Interior in view of its importance to the three major monotheistic religions.[10]

- Sharifate of Mecca (Mekke Şerifliği) (autonomous sharifate, not a vilayet)

- Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate (Cebel-i Lübnan Mutasarrıflığı): sanjak or mutessariflik, dependent directly on the Porte.[11]

- Principality of Samos (Sisam Beyliği) (island with special status)

- Tunis Eyalet (Tunus Eyaleti) (autonomous eyalet, ruled by hereditary beys)

Encyclopædia Britannica on the late Ottoman administration

For administrative purposes the immediate possessions of the sultan are divided into vilayets (provinces), which are again subdivided into sanjaks or mutessarifliks (arrondissements), these into kazas (cantons), and the kazas into nahies (parishes or communes). A vali or governor-general, nominated by the sultan, stands at the head of the vilayet, and on him are directly dependent the kaimakams, mutassarifs, deftardars and other administrators of the minor divisions. All these officials unite in their own persons the judicial and executive functions, under the "Law of the Vilayets", which made its appearance in 1861, and purported, and was really intended by its framers, to confer on the provinces a large measure of self-government, in which both Mussulmans and non-Mussulmans should take part. It really, however, had the effect of centralizing the whole power of the country more absolutely than ever in the sultan's hands, since the Valis were wholly in his undisputed power, while the ex officio official members of the local councils secured a perpetual Mussulman majority.[12]

Maps

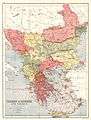

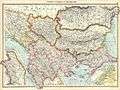

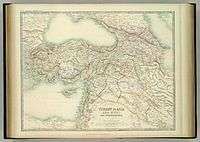

Vilayets of Europe in 1870

Vilayets of Europe in 1870_The_Bosphorus_and_Vicinity._Copyright%2C_1877%2C_by_O.W._Gray_%26_Son.jpg) Vilayets in 1877

Vilayets in 1877_The_Bosporus_%26_Constantinople._(with)_Crete_or_Candia._By_Keith_Johnston%2C_F.R.S.E._Keith_Johnston's_General_Atlas._Engraved%2C_Printed%2C_and_Published_by_W._%26_A.K._Johnston%2C_Edinburgh_%26_London.jpg) Vilayets of Europe in 1893

Vilayets of Europe in 1893.jpg) Vilayets of Asia in 1897

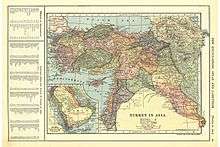

Vilayets of Asia in 1897 Vilayets of Asia in 1909

Vilayets of Asia in 1909 Vilayets of Europe in 1910

Vilayets of Europe in 1910 Vilayets of Asia in 1911

Vilayets of Asia in 1911

See also

- Provinces of Turkey

- Six vilayets, the Armenian vilayets of the empire

- Vilayet Law

Notes

References

- Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg: Orient-Institut Istanbul. p. 21-51. (info page on book at Martin Luther University) // CITED: p. 41-43 (PDF p. 43-45/338).

- File:Solun Newspaper 1869-03-28 in Bulgarian.jpg

- Birken, Andreas (1976). Die Provinzen des Osmanischen Reiches. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients (in German). 13. Reichert. p. 22. ISBN 9783920153568.

- Report of a Committee set up to consider certain correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon (his majesty's high commissioner in egypt) and the Sharif of Mecca in 1915 and 1916 Archived 2015-06-21 at the Wayback Machine, ANNEX A, para. 10. British Secretary of State for the Colonies, 16 maart 1939 (doc.nr. Cmd. 5974). unispal Archived October 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Birken, Andreas (1976). Die Provinzen des Osmanischen Reiches. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients (in German). 13. Reichert. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9783920153568.

- Birken, Andreas (1976). Die Provinzen des Osmanischen Reiches. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients (in German). 13. Reichert. p. 2324. ISBN 9783920153568.

- Abel Pavet de Courteille (1876). État présent de l'empire ottoman (in French). J. Dumaine. pp. 91–96.

- A handbook of Asia Minor Published 1919 by Naval staff, Intelligence dept. in London. Page 226

-

- Palestine; A Modern History (1978) by Adulwahab Al Kayyali. Page 1

-

-

Further reading

- Sublime Porte (1867). Sur la nouvelle division de l’Empire en gouvernements généraux formés sous le nom de Vilayets. Constantinople. - About the Law of the Vilayets

External links

- Vilayet Law of 1864, official translation to French pp. 36–45, in Young, George, Corps de droit ottoman; recueil des codes, lois, règlements, ordonnances et actes les plus importants du droit intérieur, et d'études sur le droit coutumier de l'Empire ottoman, Volume 1, 1905.

- Vilayet Law of 1867, in French, in Législation ottomane, published by Gregory Aristarchis and edited by Demetrius Nicolaides, Volume 2