Palazzo Sacchetti

Palazzo Sacchetti (formerly Palazzo Ricci) is a palazzo in Rome, important for historical and artistic reasons.

| Palazzo Sacchetti | |

|---|---|

.jpg) The facade of Palazzo Sacchetti along Via Giulia | |

| |

| Former names | Palazzo Ricci |

| General information | |

| Status | In use |

| Type | Palazzo |

| Architectural style | Renaissance |

| Location | Rome |

| Address | Via Giulia 52 |

| Coordinates | 41°53′55″N 12°27′57″E |

| Groundbreaking | 1542 |

| Completed | 1552 |

| Owner | Sacchetti family De Balkany family |

| Technical details | |

| Material | brick, travertine |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Antonio da Sangallo the Younger Nanni di Baccio Bigio or Annibale Lippi |

The building was designed and owned by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger and completed by Nanni di Baccio Bigio or his son Annibale Lippi. After Sangallo, the palace belonged among others to the Ricci, Ceoli and Sacchetti, important families of the Roman nobility. Among the artworks that decorate the interior, the cycle of frescoes depicting the Storie di David by Francesco Salviati represents an important work of Mannerism. The palace also housed hundreds of paintings that would become the nucleus of the Pinacoteca Capitolina. Palazzo Sacchetti is widely considered the most important palace in Via Giulia.[1]

Location

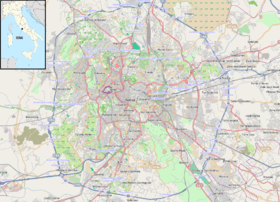

The building is located in Rome, in the Ponte Rione, at n. 66 of Via Giulia,[1] on the western side of the northern part of the street. To the southeast it overlooks Vicolo del Cefalo, to the northwest Vicolo Orbitelli, while to the southwest, with the side once reflecting in the Tiber, it faces Lungotevere dei Sangallo.[2][3]

History

Antonio da Sangallo the Younger built on buildings and land that had been sold to him in 1542 by the Vatican Chapter this palace, which was one of the three properties of the architect on Via Giulia.[1] On the main façade of the building still stands out the coat of arms – today chiselled – of the Pope and his main client, Paul III Farnese (r. 1534-1549), together with the inscription:[1]

TV MIHI QVODCVMQVE HOC RERVM EST

Everything I have, I got from you

alluding perhaps to the generosity of the pope towards him.[1] On the same façade is still visible the plaque walled ab antiquo that attests the ownership of the architect:[1]

DOMVS / ANTONII / SANGALLI / ARCHITECTI / MDXLIII

House of Antonio da Sangallo architect 1543

The attribution of the building to Antonio is also confirmed by various drawings and sketches by the artist's own hand of his house by San Biagio preserved in the Uffizi[4] and by Giorgio Vasari, who writes that Sangallo:[5]

Rifondò ancora in Roma, per difendersi dalle piene quando il Tevere ingrossa, la casa sua in strada Giulia. E non solo diede principio, ma condusse a buon termine il palazzo che egli abitava vicino a San Biagio, che oggi è del cardinale Riccio da Monte Pulciano, che l’ha finito con grandissima spesa e con ornatissime stanze, oltre quelle che Antonio vi aveva speso, che erano state migliaia di scudi.

In Rome renewed the foundations, to defend himself from floods when the Tiber swells, of his house in Via Giulia. And not only did he begin, but he brought to a good end the palace where he lived near San Biagio, which today belongs to Cardinal Riccio da Monte Pulciano, who finished it at great expense and with very ornate rooms, in addition to those that Antonio had expended there, which had been thousands of scudi.

Sangallo's original project foresaw two storeys plus the attic, each with five windows.[1]

After Antonio's death in 1546, on 23 July 1552 his son Orazio sold the property to Cardinal Giovanni Ricci from Montepulciano, Tuscany, for the sum of 3,145 Roman scudi.[6] The cardinal had the palace freed from the censo tax (the fact is remembered on a plaque on Vicolo del Cefalo) and had it completed, merging adjacent houses purchased by him.[6] The author of the works was probably Nanni di Baccio Bigio,[1][6] or according to another hypothesis (based on the stylistic kinship between the palace and the suburban villa – the future Villa Medici – that the cardinal had built in those same years) his son Annibale Lippi.[7][8]

On this occasion the façade of the palace on Via Giulia was extended by adding two windows, while the main door was enlarged and moved to the right.[1] Between 1552 and 1554 the cardinal also had the piano nobile decorated by Francesco Salviati and other mannerist artists.[1]

Economic difficulties forced him in 1557 to a fictitious sale of the palace for 25,000 scudi to his friend Tommaso Marino di Terranova, a very rich Genoese financier who in the same period had the Palazzo Marino built in Milan. Marino allowed the Cardinal to live there and sold it to the latter’s nephew Giulio Ricci in 1568.[6]

When the cardinal died in 1574, his nephew Giulio sold it definitively to the Pisan banker Tiberio Ceuli.[2] The Ceuli family invested a lot in the building: the wing towards Vicolo Orbitelli, the courtyard and the completion of the rear part are due to it.[2] They also had the façades towards the river decorated by Giacomo Rocca with sgraffiti, of which few traces remain today.[2] The Ceuli also had the building raised one floor higher, decorating the cornice with the heraldic motif of the double eight-pointed star taken from their coat of arms.[4][2] The name of the house, corrupted in Cefalo (English: mullet), has passed to the alley that runs along the palace to the south, called Vicolo del Cefalo.[2]

In 1608, the Ceuli family sold the Palace to Cardinal Ottavio Acquaviva d'Aragona, whose coats of arms still decorate the chapel of the palace, built by him.[2] The Acquaviva family sold the building in turn in 1649 to Cardinal Giulio Cesare Sacchetti, a member of the noble Florentine family.[9] The Cardinal had Carlo Rainaldi carry out the last important works in the building, modifying the rear part and having the stairs built that went down to the Tiber. With him the palace acquired a great importance, hosting a picture gallery rich of almost 700 paintings.[9] His heirs sold part of it in 1748 to Pope Benedict XIV (r.1740-1758), who made it the original nucleus of the Pinacoteca Capitolina.[9]

The Sacchetti family has been in possession of the palace since then until 2015: in that year, part of the palace corresponding to the entire piano nobile inherited by Giovanna Zanuso, spouse of the deceased Giulio Sacchetti, was sold to the banker Robert De Balkany.[10] After the latter's death it has been put on sale again by Sotheby's.[11]

Architecture

The main façades of the palace overlook Via Giulia and Vicolo del Cefalo, where there are 9 windows.[12] Both façades are made of brick with travertine windows, while the portal on Via Giulia is made of marble, and is surmounted by a balcony surrounded by fine bronze balustrades.[12] On the ground floor, which is attributed to Sangallo, there are 6 windows of the inginocchiato (English: knelt) type.[13] Each of them, closed by a grille, has an architrave and frame, and a protruding threshold supported by two large corbels.[12][13] Between each pair of these opens a small window that gives light to the cellars.[13]

The first floor has a row of 7 windows with frames and corbels;[12] among these, the central one has been enlarged to fit the balcony.[12] Above one of the windows is the chiselled coat of arms of Paul III.[12]

Each window on the first floor is surmounted by a small window of approximately square shape.[12]

The second floor also has seven windows, but simpler than those on the first floor.[12] A corbelled cornice concludes the building.[12] Near the left corner of the facade on Via Giulia there is a fountain embedded in a niche flanked by caryatids.[12] In its interior there is a cupid with two dolphins and the chiseled Ceuli coat of arms.[12] The motif of the fountain is inspired by the arms of the house of Ceuli.

The courtyard is bordered by an arcade (the lateral arches being infilled) on Doric pillars,[9] and ends with a doric frieze adorned with weapons and the Ceuli coat of arms.[12] In the middle of the courtyard there is a nymphaeum adorned with stuccoes.[9] On the left there is an overhang caused by the chapel added by the Acquaviva family, probably made by Agostino Ciampelli to a design by Pietro da Cortona.[12] The Sacchetti coat of arms was added later.

On the side towards the Lungotevere the palace ends with a loggia once overlooking the river, created by the Ceuli and modified by the Sacchetti, adorned with a colossal marble head (possibly Juno)[14] and two mascarons.[9] The loggia is the backdrop to a citrus garden.[14]

Interiors and decoration

In the hallway is a Roman relief of the third century AD, depicting an episode of the reign of Septimius Severus. Above this is a Madonna and child of 1400's Florentine school.[15]

On the first floor, noteworthy is the hall of the audiences of Cardinal Ricci, called the Sala dei Mappamondi from two globes (Italian: Mappamondo) – one terrestrial and one celestial – by Vincenzo Coronelli placed there:[9][16] the presence of a canopy testifies to the frequent papal visits.[9] It is decorated with frescoes by mannerist painter Francesco Salviati and aids, painted in 1553–1554 and depicting Stories of David (the descriptions start from the wall to the right of those who look at the windows in a clockwise direction).[15]

- First wall

- Third wall

- David speaks to the soldiers;

- Death of Absalom;

- Announcement to David of Absalom's death;

- Fourth wall

- David saves Saul;

- David dances before the Ark of the Covenant in the presence of Mikal;

- David saved from Mikal;

On Vicolo del Cefalo there are 4 rooms adorned with stuccoes and frescoes, while a group of French and Italian mannerist artists, including Maitre Ponce, Girolamo da Faenza known as Fantino, Marco Marcucci from Faenza, Giovanni Antonio Veneziano, Marco Duval known as il sordo (Marco Francese), Stefano Pieri (Stefano da Firenze), Nicolò da Bruyn, and G. A. Napolitano decorated other rooms towards the garden between 1553 and 1556 with grotesques, Old Testament scenes and mythological scenes.[15]

The Gallery, converted into a dining room and banquet hall, is situated towards the Tiber and decorated with paintings depicting biblical subjects by Pietro da Cortona.[9]

Also noteworthy is the dining room built by Cardinal Ricci in 1573, decorated with frescoes on the walls by Giacomo Rocca from Salerno, depicting pairs of sibyls and prophets on the model of the Sistine Chapel.[9][17] The room is also adorned with two frescoes by Pietro da Cortona depicting The Holy Family and Adam and Eve.[15]

The ceiling of the dining room was made in 1573 by woodcarver Ambrogio Bonazzini,[17] who later sculpted the ceiling of the Oratorio del Gonfalone.[15]

References

- Pietrangeli (1981), p. 40

- Pietrangeli (1981), p. 42

- Pietrangeli (1981), inside front cover

- Mergé (2015), p. 45

- Giorgio Vasari: Vita d'Antonio da Sangallo Architettore Fiorentino (1568)

- Fragnito (2016)

- Callari (1932), p. 254

- Portoghesi (1970), p. 196

- Mergé (2015), p. 46

- "Come vendere un pezzo del Colosseo" (in Italian). 10 February 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- "Palazzo Sacchetti, a pearl of the late reinassance in the heart of Rome". Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- Pietrangeli (1981), p. 44

- Portoghesi (1970), p. 356

- Pietrangeli (1981), p. 48

- Pietrangeli (1981), p. 46

- "Palazzo Sacchetti" (in Italian). Comune di Roma. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Mergé (2015), p. 47

Sources

- Vasari, Giorgio (1568). Le vite de’ più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri (in Italian). Firenze: Giunti.

- Luigi Callari (1932). I Palazzi di Roma (in Italian). Roma: Ugo Sofia-Moretti.

- Paolo Portoghesi (1970). Roma del Rinascimento (in Italian). Milano: Electa.

- Carlo Pietrangeli (1981). Guide rionali di Roma (in Italian). Ponte (IV) (3 ed.). Roma: Fratelli Palombi Editori.

- Patrizio Mario Mergé (2015). Palazzi storici a Roma (in Italian). Roma: ADSI.

- Gigliola Fragnito (2016). "Giovanni Ricci". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (in Italian). 87. Roma: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

External links