Veronese Riddle

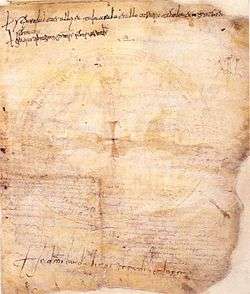

The Veronese Riddle (Italian: Indovinello veronese) is a riddle written in late Vulgar Latin on the margin of a parchment, on the Verona Orational, probably in the 8th or early 9th century, by a Christian monk from Verona, in northern Italy. It is an example of the internationally widespread writing-riddle, very popular in the Middle Ages and still in circulation in recent times. Discovered by Luigi Schiaparelli in 1924, it is considered the oldest existing document in the Italian language along with the Placiti Cassinesi.[1]

| Veronese Riddle | |

|---|---|

Original text | |

| Full title | Indovinello Veronese (Italian) |

| Language | Early Italian/late Vulgar Latin |

| Date | 8th or early 9th century |

| Provenance | Verona, Italy |

| Genre | Riddle |

| This article is part of the series on the |

| Italian language |

|---|

| History |

| Literature and other |

| Grammar |

| Alphabet |

| Phonology |

Text

The text, with a literal translation, runs:

Se pareba boves |

In front of him (he) led oxen |

Explanation

The lines of this riddle tell us of a somebody with oxen (boves) who used to plow white fields (alba pratalia) with a white plow (albo versorio), sowing a black seed (negro semen). This person is the writer himself, the monk whose business is to copy old manuscripts. The oxen are his fingers which draw a white feather (the white plow) across the page (the white fields), leaving black ink marks (black seed).

Origins of the Indovinello

This document dates to the late 10th-early 11th century, and the above text was followed by a small thanksgiving prayer in Latin: gratias tibi agimus omnip(oten)s sempiterne d(eu)s ("we thank you almighty everlasting God"). These lines were written on codex LXXXIX (89) of the Biblioteca Capitolare di Verona. The parchment, discovered by Schiapparelli in 1924, is a Mozarabic oration by the Spanish Christian Church, i.e. a document in a Romance language first written in Spain in an area influenced by the Moorish culture, probably around Toledo. It was then brought to Cagliari and then to Pisa before reaching the Chapter of Verona.

Text analysis and comments

Many more European documents seem to confirm that the distinctive traits of Romance languages occurred all around the same time (e.g. France's Serments de Strasburg). Though initially hailed as the earliest document in Italian in the first years following Schiapparelli's discovery, today the record has been disputed by many scholars from Bruno Migliorini to Cesare Segre and Francesco Bruni, who have placed it at the latest stage of Vulgar Latin, though this very term is far from being clear-cut, and Migliorini himself considers it dilapidated. At present, however, the Placito Capuano (960 AD; the first in a series of four documents dated 960-963 AD issued by a Capuan court) is considered to be the first document ever written in Italian, although Migliorini concedes that since the Placito was put on record as an official court proceeding (and signed by a notary), Italian must have been widely spoken for at least one century.

Some words do stick to the rules of Latin grammar (boves with -es for the accusative masculine plural, alba with -a suffix for the neuter plural). Yet more are distinctly Italian, with no cases and producing the typical ending of Italian verbs: pareba (It. pareva), araba (It. arava), teneba (It. teneva), seminaba (It. seminava) instead of Latin imperfect tense parebat, arabat, tenebat, seminabat. Albo versorio and negro semen have replaced Latin album versorium and nigrum semen (accusative). Versorio is still the word for "plow" in today's Veronese dialect (and the other varieties of Venetian language) as the verb parar is still the word for 'push on', 'drive', 'lead' (in Italian spingere, guidare). Michele A. Cortelazzo and Ivano Paccagnella say that the plural -es of boves may well be considered Ladin and therefore not Latin, but Romance too. Albo is early Italian, especially since Germanic blank entered Italian usage later, leading to current Italian bianco ("white").

See also

- Latin language

- Romance languages

- Venetian language

- Italian language

References

- https://web.archive.org/web/20060507235754/http://www.multimediadidattica.it/dm/origini/origini.htm. Archived from the original on May 7, 2006. Retrieved April 18, 2007. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

- Notes

- Bruno Migliorini, Storia della lingua italiana. Firenze, Sansoni, 1987.

- Aldo Giudice, Giovanni Bruni, Problemi e scrittori della lingua italiana. Torino, Paravia 1973, vols.

- AA.VV. Il libro Garzanti della lingua italiana. Milano, Garzanti, 1969.

- Lucia Cesarini Martinelli, La filologia. Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1984.

External links

- (in Italian) Indovinello Veronese

- (in Italian) Indovinello Veronese