The Masque of the Red Death

"The Masque of the Red Death" (originally published as "The Mask of the Red Death: A Fantasy") is a short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in 1842. The story follows Prince Prospero's attempts to avoid a dangerous plague, known as the Red Death, by hiding in his abbey. He, along with many other wealthy nobles, hosts a masquerade ball in seven rooms of the abbey, each decorated with a different color. In the midst of their revelry, a mysterious figure disguised as a Red Death victim enters and makes his way through each of the rooms. Prospero dies after confronting this stranger, whose "costume" proves to contain nothing tangible inside it; the guests also die in turn.

| "The Masque of the Red Death" | |

|---|---|

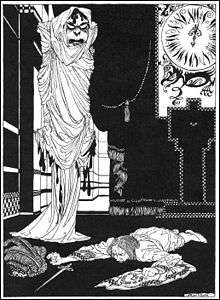

.tif.jpg) Illustration for "The Masque of the Red Death" by Harry Clarke, 1919 | |

| Author | Edgar Allan Poe |

| Original title | "The Mask of the Red Death: A Fantasy" |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Gothic fiction, horror |

| Publisher | Graham's Magazine |

| Publication date | May 1842 |

Poe's story follows many traditions of Gothic fiction and is often analyzed as an allegory about the inevitability of death, though some critics advise against an allegorical reading. Many different interpretations have been presented, as well as attempts to identify the true nature of the eponymous disease. The story was first published in May 1842 in Graham's Magazine and has since been adapted in many different forms, including a 1964 film starring Vincent Price. Poe's short story has also been alluded to by other works in many types of media.

Plot summary

The story takes place at the castellated abbey of the "happy and dauntless and sagacious" Prince Prospero. Prospero and 1,000 other nobles have taken refuge in this walled abbey to escape the Red Death, a terrible plague with gruesome symptoms that has swept over the land. Victims are overcome by "sharp pains", "sudden dizziness", and "profuse bleeding at the pores", and die within half an hour. Prospero and his court are indifferent to the sufferings of the population at large; they intend to await the end of the plague in luxury and safety behind the walls of their secure refuge, having welded the doors shut.

Prospero holds a masquerade ball one night to entertain his guests in seven colored rooms of the abbey. Each of the first six rooms is decorated and illuminated in a specific color: blue, purple, green, orange, white, and violet. The last room is decorated in black and is illuminated by a scarlet light, "a deep blood color" cast from its stained glass windows. Because of this chilling pairing of colors, very few guests are brave enough to venture into the seventh room. A large ebony clock stands in this room and ominously chimes each hour, upon which everyone stops talking or dancing and the orchestra stops playing. Once the chiming stops, everyone immediately resumes the masquerade.

At the chiming of midnight, the revelers and Prospero notice a figure in a dark, blood-splattered robe resembling a funeral shroud. The figure's mask resembles the rigid face of a corpse and exhibits the traits of the Red Death. Gravely insulted, Prospero demands to know the identity of the mysterious guest so they can hang him. The guests, too afraid to approach the figure, instead let him pass through the six chambers. The Prince pursues him with a drawn dagger and corners the guest in the seventh room. When the figure turns to face him, the Prince lets out a sharp cry and falls dead. The enraged and terrified revelers surge into the black room and forcibly remove the mask and robe, only to find to their horror that there is nothing underneath. Only then do they realize the costume was empty and all of the guests contract and succumb to the disease. The final line of the story sums up, "And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all."

Analysis

Directly influenced by the first Gothic novel, Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, in "The Masque of the Red Death" Poe adopts many conventions of traditional Gothic fiction, including the castle setting.[1] The multiple single-toned rooms may be representative of the human mind, showing different personality types. The imagery of blood and time throughout also indicates corporeality. The plague may, in fact, represent typical attributes of human life and mortality,[2] which would imply the entire story is an allegory about man's futile attempts to stave off death (a commonly accepted interpretation).[3]:137 However, there is much dispute over how to interpret "The Masque of the Red Death"; some suggest it is not allegorical, especially due to Poe's admission of a distaste for didacticism in literature.[3]:134 If the story really does have a moral, Poe does not explicitly state that moral in the text.[4]

Blood, emphasized throughout the tale, along with the color red, serves as a dual symbol, representing both death and life. This is emphasized by the masked figure – never explicitly stated to be the Red Death, but only a reveler in a costume of the Red Death – making his initial appearance in the easternmost room, which is colored blue, a color most often associated with birth.[3]:141

Although Prospero's castle is meant to keep the sickness out, it is ultimately an oppressive structure. Its maze-like design and tall and narrow windows become almost burlesque in the final black room, so oppressive that "there were few of the company bold enough to set foot within its precincts at all".[5] Additionally, the castle is meant to be an enclosed space, yet the stranger is able to sneak inside, suggesting that control is an illusion.[6]

Like many of Poe's tales, "The Masque of the Red Death" has been interpreted autobiographically, by some. In this point of view, Prince Prospero is Poe as a wealthy young man, part of a distinguished family much like Poe's foster parents, the Allans. Under this interpretation, Poe is seeking refuge from the dangers of the outside world, and his portrayal of himself as the only person willing to confront the stranger is emblematic of Poe's rush towards inescapable dangers in his own life.[7] Prospero is also the name of a central character in William Shakespeare's The Tempest.[8]

The "Red Death"

The disease called the Red Death is fictitious. Poe describes it as causing "sharp pains, and sudden dizziness, and then profuse bleeding at the pores" leading to death within half an hour.

The disease may have been inspired by tuberculosis (or consumption, as it was known then), since Poe's wife Virginia was suffering from the disease at the time the story was written. Like the character Prince Prospero, Poe tried to ignore the terminal nature of the disease.[9] Poe's mother Eliza, brother William, and foster mother Frances had also died of tuberculosis. Alternatively, the Red Death may refer to cholera; Poe witnessed an epidemic of cholera in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1831.[10] Others have suggested the pandemic is actually bubonic plague, emphasized by the climax of the story featuring the Red Death in the black room.[11] One writer likens the description to that of a viral hemorrhagic fever or necrotizing fasciitis.[12] It has also been suggested that the Red Death is not a disease or sickness at all but a weakness (like original sin) that is shared by all of humankind inherently.[3]:139–140

Publication history

Poe first published the story in the May 1842 edition of Graham's Lady's and Gentleman's Magazine as "The Mask of the Red Death", with the tagline "A Fantasy". This first publication earned him $12.[13] A revised version was published in the July 19, 1845 edition of the Broadway Journal under the now-standard title "The Masque of the Red Death."[14] The original title emphasized the figure at the end of the story; the new title puts emphasis on the masquerade ball.[15]

Adaptations

Audio adaptations

- Basil Rathbone read the entire short story in his Caedmon LP recording The Tales of Edgar Allan Poe (early 1960s). Other audiobook recordings have featured Christopher Lee, Hurd Hatfield, Martin Donegan and Gabriel Byrne as readers.

- The story was adapted by George Lowther for a broadcast on the CBS Radio Mystery Theater (January 10, 1975), starring Karl Swenson and Staats Cotsworth.

- A radio reading was performed by Winifred Phillips, with music she composed. The program was produced by Winnie Waldron as part of National Public Radio's Tales by American Masters series.

- Eros Ramazzotti's song "Lettera al futuro" ("Letter to the future"), from his 1996 album Dove c'è musica, retells the main events of the story in a simplified form, without mentioning any specific characters or names but vaguely connecting the plague mentioned in the story to AIDS, and concludes with the singer's hope, addressed to an imaginary unborn child, that such events will not happen any longer in the future.[16]

- While many adaptions of the story have been created in the realm of classical music, composer Jason Mulligan's concert drama of the same title is the only known setting that uses Poe's story unaltered in its entirety.[17]

Comics adaptations

- In 1952, Marvel published "The Face of Death" in Adventures Into Weird Worlds #4. Adaptation and art were by Bill Everett.

- In 1952, Charlton published "The Red Death" in The Thing #2. Adaptation and art were by Bob Forgione.

- In 1960, Editora Continental (Brazil) published "A Mascara Da Morte Rubra" in Classicos De Terror #9. Adaptation and art by Manoel Ferreira. It was reprinted by Editora Taika in Album Classicos De Terror #11 (1974) and by Editora Vecchia in Spektro #6 (1978).

- In 1961, Marvel published "Masquerade Party" in Strange Tales #83, with story and art by Steve Ditko. It was reprinted by Editora Taika (Brazil) in Almanaque Fantastic Aventuras #1 (1973) and by Marvel in Chamber of Chills #16 (1975).

- In 1964, Dell published "The Masque of the Red Death", adapted from the 1964 film, art by Frank Springer.

- In 1967, Warren published "The Masque Of The Red Death" in Eerie #12. Adaptation was by Archie Goodwin, art by Tom Sutton. This version has been reprinted multiple times.

- In 1967, Editora Taika published "A Mascara Da Morte Rubra" in Album Classicos De Terror #3. Adaptation by Francisco De Assis, art by Nico Rosso with J.B. Rosa. This was reprinted in Almanaque Classicos De Terror #15 (1976).

- In 1969, Marvel published "The Day of the Red Death" in Chamber of Darkness #2. Adaptation by Roy Thomas, art by Don Heck. This was reprinted by La Prensa (Mexico) in El Enterrador #4 (1970) and by Marvel in Chamber of Darkness Special #1 (1972).

- In 1972, Milano Libri Edizioni (Italy) published "La Maschera della Morte Rossa" in Linus #91. Adaptation and art were by Dino Battaglia. This was reprinted in Corto Maltese #7 (1988) and multiple other times.

- In 1974, Skywald published "The Masque of the Red Death" in Psycho #20. Adaptation by Al Hewetson, art by Ricardo Villamonte. This was reprinted by Garbo (Spain) in Vampus #50 (1975) and by Eternity in The Masque Of The Red Death and Other Stories #1 (1988).

- In 1975, Warren published "Shadow" in Creepy #70. Adaptation by Richard Margopoulos, art by Richard Corben. The ending was changed to incorporate elements of "The Masque of the Red Death". This was reprinted multiple times.

- In 1975, Charlton published "The Plague" in Haunted #22. Adaptation by Britton Bloom, art by Wayne Howard. This was reprinted in Haunted #45 (1979) and by Rio Grafica Editora Globo (Portugal) in Fetiche #1 (1979).

- In 1975, Ediciones Ursus (Spain) published "La Mascara de la Muerte Roja" in Macabro #17. Art by Francisco Agras.

- In 1979, Bloch Editores S.A. (Brazil) published "A Mascara da Morte Rubra" in Aventuras Macabras #12. Adaptation by Delmir E. Narutoxde, art by Flavio Colin.

- In 1982, Troll Associates published "The Masque of the Red Death" as a children's book. Adaptation by David E. Cutts, art by John Lawn.

- In 1982, Warren published "The Masque of The Red Death" in Vampirella #110. Adaptation by Rich Margopoulos, art by Rafael Aura León. This has been reprinted multiple times.

- In 1984, Editora Valenciana (Spain) published "La Mascara de la Muerte Roja" in SOS #1. Adaptation and art by A.L. Pareja.

- In 1985, Edizioni Editiemme (Italy) published "La Masque De La Morte Rouge" in Quattro Incubi. Adaptation and art were by Alberto Brecchi. This has been reprinted multiple times.

- In 1987, Kitchen Sink Press published "The Masque of The Red Death" in Death Rattle v.2 #13. Adaptation and art by Daryl Hutchinson.

- In 1988, Last Gasp published "The Masque of The Red Death" in Strip Aids U.S.A. Adaptation and art by Steve Leialoha.

- In 1995, Mojo Press published "The Masque of The Red Death" in Weird Business. Adaptation by Erick Burnham, art by Ted Naifeh.

- In 1999, Albin Michel – L'Echo des Savanes (France) published "De La Mascara De La Muerte Roja" in Le Chat Noir. Adaptation and art were by Horacio Lalia. This has been reprinted multiple times.

- In 2004, Eureka Productions published "The Masque of the Red Death" in Graphic Classics #1: Edgar Allan Poe (2nd edition). Adaptation by David Pomplun, art by Stanley W. Shaw. This has been reprinted in the 3rd edition (2006), and in Graphic Classics #21: Edgar Allan Poe's Tales Of Mystery (2011).

- In 2008, Go! Media Entertainment published Wendy Pini's Masque of the Red Death. Adaptation and art by Wendy Pini. This version is an erotic, science-fiction illustrated webcomic, set in a technological future. Go! Media also published in print the first third of the graphic novel. In 2011 Warp Graphics published the complete 400-page work in one volume.

- In 2008, Sterling Press published "The Masque of The Red Death" in Nevermore (Illustrated Classics): A Graphic Adaptation of Edgar Allan Poe's Short Stories. Adaptation by Adam Prosser, art by Erik Rangel.

- In 2013, Dark Horse published "The Masque of the Red Death" in The Raven And The Red Death. Adaptation and art by Richard Corben. This has been reprinted in Spirits of the Dead (2014).

- In spring 2017, UDON Entertainment's Manga Classics line published The Stories of Edgar Allan Poe, which included a manga format adaptation of "The Masque of the Red Death".[18]

Film adaptations

- The story was adapted by Roger Corman as a film, The Masque of the Red Death (1964), starring Vincent Price.

- Corman produced, but did not direct, a remake of the film in 1989, starring Adrian Paul as Prince Prospero.[15]

- Corman also voiced Prince Prospero in "The Masque of the Red Death" segment of Raúl García's animated anthology Extraordinary Tales (2015).

- Huayi Brothers Media and CKF Pictures in China announced in 2017 plans to produce a film of Akira Kurosawa's previously unfilmed screenplay of "The Mask of the Red Death" for 2020.[19]

In popular culture

See also

References

- "The Castle of Otranto: The creepy tale that launched gothic fiction". BBC News. December 13, 2014.

- Fisher, Benjamin Franklin (2002). "Poe and the Gothic tradition". In Hayes, Kevin J. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521793262.006. ISBN 0-521-79727-6.

- Roppolo, Joseph Patrick (1967). "Meaning and 'The Masque of the Red Death'". In Regan, Robert (ed.). Poe: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Quinn, Arthur Hobson (1998). Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 331. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9.

- Laurent, Sabrina (July 2003). "Metaphor and Symbolism in 'The Masque of the Red Death'". Boheme: An Online Magazine of the Arts, Literature, and Subversion. Archived from the original on 2006-03-04.

- Peeples, Scott (2002). "Poe's 'constructiveness' and 'The Fall of the House of Usher'". In Hayes, Kevin J. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe. Cambridge University Press. p. 186. doi:10.1017/CCOL0521793262.012. ISBN 0-521-79727-6.

- Rein, David M. (1960). Edgar A. Poe: The Inner Pattern. New York: Philosophical Library. p. 33.

- Barger, Andrew (2011). Phantasmal: The Best Ghost Stories 1800-1849. Bottletree Books. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-933747-33-0.

- Silverman, Kenneth (1991). Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial. pp. 180–181. ISBN 0-06-092331-8.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1992). Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press. p. 133. ISBN 0-8154-1038-7.

- "The Masque of the Red Death". Cummings Study Guides.

- Waring, R. H.; Steventon, G. B.; Mitchell, S. C. (2007). Molecules of Death (2nd ed.). London: Imperial College Press.

- Ostram, John Ward (1987). "Poe's Literary Labors and Rewards". In Fisher, Benjamin Franklin (ed.). Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society. p. 39. ISBN 9780961644918.

- "Edgar Allan Poe — "The Masque of the Red Death"". Edgar Allan Poe Society. Baltimore.

- Sova, Dawn B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books. pp. 149–150. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X.

- "Lettera al futuro". Lyrics Translate.

- "The Masque of the Red Death". Jason Mulligan. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- Hodgkins, Crystalyn (July 21, 2016). "Udon Ent. to Release Street Fighter Novel, Dragon's Crown Manga". Anime News Network.

- Raup, Jordan (March 5, 2017). "Unfilmed Akira Kurosawa script the mask of the black death will be produced in china". The Film Stage.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Masque of the Red Death. |

- "The Masque of the Red Death" at Project Gutenberg

- "The Masque of the Red Death" with annotated vocabulary at PoeStories.com