Valladolid debate

The Valladolid debate (1550–1551) was the first moral debate in European history to discuss the rights and treatment of an indigenous people by conquerors. Held in the Colegio de San Gregorio, in the Spanish city of Valladolid, it was a moral and theological debate about the conquest of the Americas, its justification for the conversion to Catholicism, and more specifically about the relations between the European settlers and the natives of the New World. It consisted of a number of opposing views about the way natives were to be integrated into Spanish society, their conversion to Catholicism, and their rights and obligations.

.jpg)

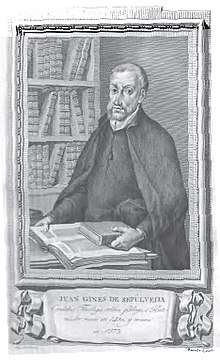

A controversial theologian, Dominican friar and Bishop of Chiapas Bartolomé de las Casas, argued that the Amerindians were free men in the natural order despite their practice of human sacrifices and other such customs, deserving the same consideration as the colonizers.[1] Opposing this view were a number of scholars and priests, including humanist scholar Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, who argued that the human sacrifice of innocents, cannibalism, and other such "crimes against nature" were unacceptable and should be suppressed by any means possible including war.[2]

Although both sides claimed to have won the disputation, there is no clear record supporting either interpretation. The affair is considered one of the earliest examples of moral debates about colonialism, human rights of colonized peoples, and international relations. In Spain, it served to establish Las Casas as the primary, though controversial defender of the Indians.[3] He and others contributed to the passing of the New Laws of 1542, which limited the encomienda system further.[4] Though they did not fully reverse the situation, the laws achieved considerable improvement in the treatment of Indians and consolidated their rights granted by earlier laws.[4] More importantly, the debate reflected a concern for morality and justice in 16th-century Spain that only surfaced in other colonial powers centuries later.

Background

Spain's colonization and conquest of the Americas inspired an intellectual debate especially regarding the compulsory Christianization of the Indians. Bartolomé de las Casas, a Dominican friar from the School of Salamanca and member of the growing Christian Humanist movement, worked for years to oppose forced conversions and to expose the treatment of natives in the encomiendas.[3] His efforts influenced the papal bull Sublimis Deus of 1537 which established the status of the Indians as rational beings. More significantly, Las Casas was instrumental in the passage of the New Laws (the Laws of the Indies) of 1542, which were designed to end the encomienda system.[4]

Moved by Las Casas and others, in 1550 the King of Spain Charles V ordered further military expansion to cease until the issue was investigated.[4][5] The King assembled a Junta (Jury) of eminent doctors and theologians to hear both sides and to issue a ruling on the controversy.[1] Las Casas represented one side of the debate. His position found some support from the monarchy, which wanted to control the power of the encomenderos. Representing the other side was Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, whose arguments were used as support by colonists and landowners who benefited from the system.[4]

Debate

Though Las Casas tried to bolster his position by recounting his experiences with the encomienda system's mistreatment of the Indians, the debate remained on largely theoretical grounds. Sepúlveda took a more secular approach than Las Casas, basing his arguments largely on Aristotle and the Humanist tradition to assert that some Indians were subject to enslavement due to their inability to govern themselves, and could be subdued by war if necessary.[1] Las Casas objected, arguing that Aristotle's definition of barbarian and natural slave did not apply to the Indians, all of whom were fully capable of reason and should be brought to Christianity without force or coercion.[4]

Sepúlveda put forward many of the arguments from his Latin dialogue Democrates alter sive de justi belli causis,[6] to assert that the barbaric traditions of certain Indians justified waging war against them. Civilized peoples, according to Sepúlveda, were obliged to punish such vicious practices as idolatry, sodomy, and cannibalism. Wars had to be waged "in order to uproot crimes that offend nature".[7]

Sepúlveda issued four main justifications for just war against certain Indians. First, their natural condition deemed them unable to rule themselves, and it was the responsibility of the Spaniards to act as masters. Second, Spaniards were entitled to prevent cannibalism as a crime against nature. Third, the same went for human sacrifice. Fourth, it was important to convert Indians to Christianity.[8]

.jpg)

Las Casas was prepared for part of his opponent's discourse, since he, upon hearing about the existence of Sepúlveda's Democrates Alter, had written in the late 1540s his own Latin work, the Apologia, which aimed at debunking his opponent's theological arguments by arguing that Aristotle's definition of the "barbarian" and the natural slave did not apply to the Indians, who were fully capable of reason and should be brought to Christianity without force.[9][10]

Las Casas pointed out that every individual was obliged by international law to prevent the innocent from being treated unjustly. He also cited Saint Augustine and Saint John Chrysostom, both of whom had opposed the use of force to bring others to Christian faith. Human sacrifice was wrong, but it would be better to avoid war by any means possible.[11]

The arguments presented by Las Casas and Sepúlveda to the junta of Valladolid remained abstract, with both sides clinging to their opposite theories that relied on similar, if not the same, theoretical authorities, which were interpreted to suit their respective arguments.[12]

Aftermath

In the end, both parties declared that they had won the debate, but neither received the desired outcome. Las Casas saw no end to Spanish wars of conquest in the New World, and Sepúlveda did not see the New Laws' restricting of the power of the encomienda system overturned. The debate cemented Las Casas's position as the lead defender of the Indians in the Spanish Empire,[3] and further weakened the encomienda system. However, it did not substantially alter Spanish treatment of the Indians.[4]

Both Sepúlveda and las Casas maintained their positions long after the end of the debate, but their revendications became less consequent when the Spanish presence in the New World became permanent.[13]

Sepúlveda’s arguments contributed to the policy of “war by fire and blood” that the Third Mexican Provincial Council implemented in 1585 during the Chichimeca War.[14] According to Lewis Hanke, while Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda became the hero of the conquistadors, his success was short lived, and his works were never published in Spain again during his lifetime.[15]

Bartholomé de Las Casas’s ideas had a more lasting impact on the decisions of the king, Philip II, as well as on history and human rights.[16] Las Casas’ criticism of the encomienda system contributed to its replacement with reducciones.[17] His testimonies on the peaceful nature of the native Americans also encouraged nonviolent policies concerning the religious conversions of the Indians in New Spain and Peru. It also helped convincing more missionaries to come to the Americas to study the indigenous people, such as Bernardino de Sahagún, who learned the native languages to discover more about their cultures and civilizations.[18]

The impact of Las Casas’ doctrine, was also limited. In 1550, the king had ordered that the conquest should cease, because the Valladolid debate was to decide whether the war was just on not. The government's orders were hardly respected, conquistadors such as Pedro de Valdivia, went on to waging war in Chile during the first half of the 1550s. Expanding the Spanish territory in the New World, was allowed again in May 1556, and a decade later, Spain started its conquest of Asia, in the Philippines.[19]

Atlantic Slave Trade

After the Valladolid debate, and the establishment of New Laws protecting the native Americans from slavery, the Atlantic slaves trade significantly increased. Historians such as Sylvia Wynter, argued that through Las Casas’ defense of the native Americans, he encouraged the use of African slaves for labour in the New World.[20] In a nineteenth century text, French priest and revolutionary, Henri Grégoire, rejected Las Casa’s implication in the Atlantic slave trade. He said that the practice of enslaving people in Africa, was started by the Portuguese, at least 30 years earlier.[21] The slave trade was never explicitly mentioned in Las Casa’s works, because he was an advocate for freedom and equal right for all men, without distinctions of countries, or skin color.[22] In this text, Grégoire explained that the idea of Las Casas endorsing the slave trade to keep the Indians for being enslaved, originated from the Spanish historian Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas.[23] His claims were confirmed by the posthume publication of Las Casas’ Historia de las Indias in 1875. In this book, Bartholomé de Las Casas expressed his regret for not being more aware of the injustice with which the Portuguese took and enslaved Africans. He explained that he had been careless in believing that the Africans were rightfully enslaved, and declared that the treatment of the African slaves was as unfair and inhumane as the treatment of the Indians.[24]

Black Legend

In Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (1552), Las Casas’ critique of the Spanish military forces in the New World, was one of the starting points of the Black Legend of Spanish colonisation. The black legend was an anti-Hispanic anti-catholic historiographic tendency which painted a highly negative image of Spanish colonisation. This text became highly popular in the Netherlands and Great Britain, where it was used to present Spain as a backwards and obscurantist country.[25] Translations of Las Casas’ work were subsequently confiscated by the Spanish Council of the Indies in response to their use as anti-Spanish propaganda.[26] But the fact that the Valladolid debate took place shows that the Spanish were concerned about the ethical consequence of their conquests, often more so than the invading forces in North America where the extermination of the native Americans was publicly accepted until much later.[27]

Reflection in art

In 1938 the story of the German writer Reinhold Schneider Las Casas and Charles V (Las Casas vor Karl V.) was published.

In 1992 the Valladolid debate became an inspiration source for Jean-Claude Carrière who published the novel La Controverse de Valladolid (Dispute in Valladolid). The novel was filmed for television under the same name. The director — Jean-Danielle Veren, Jean-Pierre Marielle played Las Casas, Jean-Louis Trintignant acted as Sepúlveda.

Notes

- Crow, John A. The Epic of Latin America, 4th ed. University of California Press, Berkeley: 1992.

- Ginés de Sepúlveda, Juan (trans. Marcelino Menendez y Pelayo and Manuel Garcia-Pelayo) (1941). Tratado sobre las Justas Causas de la Guerra contra los Indios. Mexico D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica. p. 155.

- Raup Wagner, Henry & Rand Parish, Helen (1967). The Life and Writings of Bartolomé de Las Casas. New Mexico: The University of New Mexico Press. pp. 181–182.

- Bonar Ludwig Hernandez. "The Las Casas-Sepúlveda Controversy: 1550-1551" (PDF). Ex Post Facto. San Francisco State University. 10: 95–104. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- Hanke, Lewis (1974). All Mankind is One: A study of the Disputation Between Bartolomé de Las Casas and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda in 1550 on the Intellectual and Religious Capacity of the American Indian. Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press. p. 67.

- Anthony Padgen: The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology, page 109. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda: Tratado sobre las Justas Causas de la Guerra contra los Indios, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1941.

- Losada, Angel (1971). Bartolome de las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and His Work. The Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 284–289.

- Angel Losada: The Controversy between Sepúlveda and Las Casas in the Junta of Valladolid, pages 280-282. The Northern Illinois University Press, 1971.

- Silvio Zavala: Aspectos Formales de la Controversia entre Sepúlveda y Las Casas en Valladolid, a mediados del siglo XVI y observaciones sobre la apologia de Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas, pages 137-162. Cuadernos Americanos 212, 1977.

- Bartolomé de Las Casas, In Defense, pages 212-215

- Brading, D.A.: The First America: the Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State 1492-1867, pages 80-88. Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Hernandez, 2015, p10

- Poole, 1965, p 115

- Hanke, 1949, p 129

- Minahane, 2014

- Minahane 2014

- Hernandez, 2015, p 9

- Minahane, 2014

- Friede, Keen, 1971, p 505

- Llorente, 1822, p 364

- Llorente, 1822, p 365

- Llorente, 1822, p 341

- Friede, Keen, 1971, p 505

- Benoit, 2013, p1

- Minahane, 2014

- Benoit, 2013, p 13

References

- Crow, John A. The Epic of Latin America, 4th ed. University of California Press, Berkeley: 1992.

- Hernandez, Bonar Ludwig (2001). "The Las Casas-Sepúlveda Controversy: 1550-1551" (PDF). Ex Post Facto. San Francisco State University. X: 95–105. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 21, 2015. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- Losada, Ángel (1971). "Controversy between Sepúlveda and Las Casas". In Juan Friede; Benjamin Keen (eds.). Bartolomé de las Casas in History: Toward an Understanding of the Man and his Work. Collection spéciale: CER. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press. pp. 279–309. ISBN 0-87580-025-4. OCLC 421424974.

- Benoit, J-L. (2013) “L’évangélisation des Indiens d’Amérique Autour de la « légende noire »”, Amerika [Online], 8 | 2013.

- Casas, B., & Llorente, J. (1822). Oeuvres de don barthélemi de las casas, évêque de chiapa, défenseur de la liberté des naturels de l'amérique : Précédées de sa vie, et accompagnées de notes historiques, additions, développemens, etc., etc., avec portrait. Paris etc.: Alexis Eymery etc.

- Friede, J. Keen, B. (1971) Bartolomé de las Casas in History : Toward an Understanding of the Man and his Work. DeKalb : Northern Illinois University Press. Digitized by Internet Archive.

- Hernandez, B. L. ( 2015). "The Las Casas-Sepúlveda Controversy: 1550-1551" . Ex Post Facto. San Francisco State University. 10: 95–104.

- Minahane, J. (2014)” The controversy at Valladolid, 1550- 1551”. Church and State. Nu.116.

- Poole, S. (1965). "War by Fire and Blood" the Church and the Chichimecas 1585. The Americas, 22(2), 115-137. doi:10.2307/979237

- Hanke, Lewis (1949) The Spanish Struggle for Justice in the Conquest of America .Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press