Vallahades

The Vallahades (Greek: Βαλαχάδες) or Valaades (Βαλαάδες) were a Greek-speaking, Muslim population who lived along the river Haliacmon in southwest Greek Macedonia, in and around Anaselitsa (modern Neapoli) and Grevena. They numbered about 17,000 in the early 20th century.[1] They are a frequently referred-to community of late-Ottoman Empire converts to Islam, because, like the Cretan Muslims, and unlike most other communities of Greek Muslims, the Vallahades retained many aspects of their Greek culture and continued to speak Greek for both private and public purposes. Most other Greek converts to Islam from Macedonia, Thrace, and Epirus generally adopted the Turkish language and culture and thereby assimilated into mainstream Ottoman society.[2]

Name

The name Vallahades comes from the Turkish-language Islamic expression vallah ("by God!"). They were called so by the Greeks, as this was one of the few Turkish words that Vallahades knew. They were also called pejoratively "Mesimerides" (Μεσημέρηδες), because their imams, uneducated and not knowing much Turkish, announced mid-day prayer by shouting in Greek "Mesimeri" ("Noon").[3] Though some Western travellers speculated that Vallahades is connected to the ethnonym Vlach,[4] this is improbable, as the Vallahades were always Greek-speaking with no detectable Vlach influences.[5]

History and culture

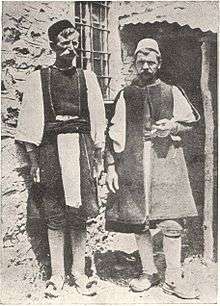

.jpg)

The Vallahades were descendants of Greek-speaking Eastern Orthodox Christians from southwestern Greek Macedonia who probably converted to Islam gradually and in several stages between the 16th and 19th centuries.[6] The Vallahades themselves attributed their conversion to the activities of two Greek Janissary sergeants (Ottoman Turkish: çavuş) in the late 17th century who were originally recruited from the same part of southwestern Macedonia and then sent back to the area by the sultan to proselytize among the Greek Christians living there.[7]

However, historians believe it more likely that the Vallahades adopted Islam during periods of Ottoman pressures on landowners in western Macedonia following a succession of historical events that influenced Ottoman government policy towards Greek community leaders in the area. These events ranged from the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–74, and especially the repercussions of the Orlov Revolt in the Peloponnese, the period of Albanian dominance in Macedonia called by Greeks the 'Albanokratia', and the policies of Ali Pasha of Ioannina, who governed areas of western Greek Macedonia and Thessaly as well as most of Epirus in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[8]

The first who is thought to describe Vallahades was François Pouqueville, who visited the area in early 19th c. He doesn't mention them as "Vallahades" and he confuses them with Turks from Vardar. However, those "Turks" are identified as Vallahades from the names of their villages mentioned by Pouqueville. A credible mid 19th c. source is the Greek B. Nikolaides who visited the area and interviewed local Vallahades and recorded oral traditions about their origins, customs etc. His work was published in french in 1859. They are also described by the Greek author and traveller B.D. Zotos Molossos in 1887.[9]

The culture of the Vallahades did not differ much from that of the local Christian Orthodox Greek Macedonians, with whom they shared the same Greek Macedonian dialect, surnames, and even knowledge of common relatives.[6] De Jong has shown how the frequent Vallahades self-reference to their identity as Turks was simply used as a synonym for Muslims. However, De Jong questioned whether they were of pure Greek origin, suggesting that they were probably of mixed Greek, Vlach, Slav, and Albanian origin but had come to speak Greek as their first language because that was the main language used by most people of Christian Orthodox origin in southwestern Macedonia and was also the language later promoted for official use by Ali Pasha.[10]

However, most historians are in agreement with Hasluck, Vakalopoulos, and other modern historians that the Vallahades were indeed of mainly Greek origin. As evidence these scholars cite the fact that as well as the absence of significant Slavic, Vlach, or Albanian elements in the Greek dialect the Vallahades spoke and the surnames they bore, the Christian traditions they preserved reflected Greek rather than Slavic, Albanian, or Vlach characteristics, while the names for geographical features like mountains and streams in the locality of the Vallahades' villages were also overwhelmingly in the Greek rather than Slavic, Vlach, or Albanian languages.[11]

Scholars who accept the evidence for the Greek ethnic origin of the Vallahades also point out that Ottoman-era Muslims converts of even part Albanian origin will very quickly have been absorbed into the wider Albanian Muslim community, the most significant in western Macedonia and neighboring Epirus being the Cham Albanians, while the descendants of Muslim converts of Bulgarian speech and origin had other groups with which they naturally identified, such as the Pomaks, Torbesh, and Poturs.[12]

In any event, Hasluk and other travelers to southwestern Greek Macedonia before the 1923 Population exchange between Greece and Turkey often noted the many religious and cultural differences between local Muslims of Greek origin on the one hand and those of Turkish origin on the other, generally characterizing the Greek Vallahades' outlook, way of life, attitude to women, and even house design as more "European", "open", and "inviting", while those of the Turks of Anatolian origin were considered as more "Asiatic", "closed", and "uninviting", adjectives that clearly reflected 18th and 19th century European tastes and biases.[13]

According to Bulgarian geographer Vasil Kanchov's statistics there was 14,373 Greeks Muslims in southwestern Macedonia at the end of the 19th century.[14] According to Greek statistics from 1904, however, there were at least 16,070 Vallahades in the kazas of Anaselitsa (Lyapchishta) and Grevena. The disparity and unreliability of such statistics is partly due to the fact that most Greek Muslims of Macedonia will simply have been defined as Turks, since Greek identity was (and still is) seen as inseparable from membership of the Greek Orthodox church and therefore becoming Turkish sufficient in-itself to entail a forfeiture of Greek-ness.[2] The fact that the Vallahades had retained their Greek language and identity set them apart from other Greek Muslims as something of an anomaly and so made them of particular interest to foreign travelers, academics, and officials.[15]

By the early 20th century the Vallahades had lost much of the status and wealth they had enjoyed in the earlier Ottoman period, with the hereditary Ottoman title of Bey their village leaders traditionally bore now carried by "simple" peasants.[6] Nevertheless, the Vallahades were still considered to be relatively wealthy and industrious peasants for their part of Macedonia, which is why their prospective inclusion in the population exchange between Greece and Turkey was opposed by the governor of Kozani. In addition to continuing to speak Greek as their first language, the Vallahades also continued to respect their Greek and Orthodox Christian heritage and churches. This also partly explains why most Vallahades probably belonged to the Bektashi dervish order, considered heretical by mainstream Sunni Muslims owing to its libertine and heterogeneous nature, combining extremist Shi'ite, pre-Islamic Turkish, and Greek/Balkan Christian elements, and so particularly favoured by Ottoman Muslim converts of southern Albanian and northern Greek Orthodox origin.

The Vallahades' preservation of their Greek language and culture and adherence to forms of Islam that lay on the fringes of mainstream Ottoman Sunni Islam explains other traits they became noted for, such as the use of an un-canonical call to prayer (adhan or ezan) in their village mosques that was itself actually in Greek rather than Arabic, their worship in mosques which did not have minarets and doubled as Bektashi lodges or tekkes (leading some visitors to southwestern Macedonia to jump to the mistaken conclusion that the Vallahades had no mosques at all), and their relative ignorance of even the fundamental practices and beliefs of their Muslim religion.[6]

Despite their relative ignorance of Islam and Turkish, the Vallahades were still considered by Christian Orthodox Greeks to have become Turkish just like the descendants of Greek converts in other parts of Greek Macedonia, who in contrast had adopted the Turkish language and identity. Consequently, pressure from the local military, the press, and the incoming Greek Orthodox refugees from Asia Minor and northeastern Anatolia meant the Vallahades were not exempted from the Population exchange between Greece and Turkey of 1922–23.[16]

The Vallahades were resettled in western Asia Minor, in such towns as Kumburgaz, Büyükçekmece, and Çatalca, Kırklareli, Şarköy, Urla or in villages like Honaz near Denizli.[17] Many Vallahades still continue to speak the Greek language, which they call Romeïka[17] and have become completely assimilated into the Turkish Muslim mainstream as Turks.[18][19]

In contrast to the Vallahades, many Pontic Greeks and Caucasus Greeks who settled in Greek Macedonia following the population exchanges were generally fluent in Turkish, which they had used as their second language for hundreds of years. However, unlike the Vallahades, these Greek communities from northeastern Anatolia and the former Russian South Caucasus had generally either remained Christian Orthodox throughout the centuries of Ottoman rule or had reverted to Christian Orthodoxy in the mid-1800, after having superficially adopted Islam in the 1500s whilst remaining Crypto-Christians.

Even after their deportation, the Vallahades continued to celebrate New Year's Day with a Vasilopita, generally considered to be a Christian custom associated with Saint Basil, but they have renamed it a cabbage/greens/leek cake and do not leave a piece for the saint.[20]

See also

- Cretan Muslims

- Greek Muslims

- Pontic Greeks

- Caucasus Greeks

- Pomaks

- Western Thrace Turks

- Cham Albanians

- The 1923 Population Exchange

Notes

- Haslett, 1927

- See Hasluck, 'Christianity and Islam under the Sultans', Oxford, 1929.

- Κ. Tsitselikis, Hemerologion 1909 of the journal "Hellas" (Κ. Τσιτσελίκης, Ημερολόγιον 1909 περιοδικού "Ελλάς"), 1908. In N. Sarantakos "Two texts on Vallahades", July 14, 2014. In Greek.

- Gustav Weigand, Alan Wace, and Maurice Thompson

- email from researcher Souli Tsetlaka to Stavros Macrakis, July 2, 2007

- See De Jong (1992) 'The Greek-speaking Muslims of Macedonia'.

- The story is given in full in Vakalopoulos, 'A History of Macedonia'.

- See De Jong, 'The Greek-speaking Muslims of Macedonia', and Vakalopoulos, 'A History of Macedonia'.

- TSOURKAS Constantinos, "Songs of Vallahades" (Gr. Τραγούδια Βαλλαχάδων), Makedonika (Gr. Μακεδονικά), 2, 461-471. In Greek language. He refers to a) F. Pouqueville, Voyage de la Grece, 2nd ed. 1826, vol. 3, p. 74-, v. 2, p. 509, 515. b) Nicolaidy B., Les Turks et la Turquie contamporaine, ... Paris 1859. vol. 2, p. 216 -. c) B.D. Zotos Molossos, Epirotic Macedonian Studies (Gr. Β.Δ. Ζώτος Μολοσσός, Ηπειρωτικαί μακεδονικαί μελέται), vol. 4, part 3. Athens 1887, p. 253, 254, passim. In Greek.

- De Jong, 'The Greek-speaking Muslims of Macedonia'.

- See Hasluk, 'Christianity and Islam under the Sultans' and Vakalopoulos, 'A History of Macedonia'.

- On these groups see Hugh Poulton, 'The Balkans: minorities and states in conflict', Minority Rights Publications, 1991.

- See Hasluk and Vakalopoulos for further observations and references to earlier European traveler accounts.

- Васил Кънчов. Македония. Етнография и статистика, София 1900, с. 283-290 (Vasil Kanchov. "Macedonia. Ethnography and statistics. Sofia, 1900, p.283-290).

- Κωνσταντίνος Σπανός. "Η απογραφή του Σαντζακίου των Σερβίων", in: "Ελιμειακά", 48-49, 2001.

- Population Exchange in Greek Macedonia by Elisabeth Kontogiorgi. Published 2006. Oxford University Press; p.199

- Koukoudis, Asterios (2003). The Vlachs: Metropolis and Diaspora. Zitros. p. 198. “In the mid-seventeenth century, the inhabitants of many of the villages in the upper Aliakmon valley-in the areas of Grevena, Anaselitsa or Voio, and Kastoria— gradually converted to Islam. Among them were a number of Kupatshari, who continued to speak Greek, however, and to observe many of their old Christian customs. The Islamicised Greek-speaking inhabitants of these areas came to be better known as “Valaades”. They were also called “Foutsides”, while to the Vlachs of the Grevena area they were also known as “Vlăhútsi”. According to Greek statistics, in 1923 Anavrytia (Vrastino), Kastro, Kyrakali, and Pigadtisa were inhabited exclusively by Moslems (i.e Valaades), while Elatos (Dovrani), Doxaros (Boura), Kalamitsi, Felli, and Melissi (Plessia) were inhabited by Moslem Valaades and Christian Kupatshari. There were also Valaades living in Grevena, as also in other villages to the north and east of the town. ...“Valaades” refers to Greek-speaking Moslems not only of the Grevena area but also of Anaselitsa. In 1924, despite even their own objections, the last of the Valaades being Moslems, were forced to leave Greece under the terms of the compulsory exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey. Until then they had been almost entirely Greek-speakers. Many of the descendants of the Valaades of Anaseltisa, now scattered through Turkey and particularly Eastern Thrace (in such towns as Kumburgaz, Büyükçekmece, and Çatalca), still speak Greek dialect of Western Macedonia, which, significantly, they themselves call Romeïka “the language of the Romii”. It is worth noting the recent research carried out by Kemal Yalçin, which puts a human face on the fate of 120 or so families from Anavryta and Kastro, who were involved in the exchange of populations. They set sail from Thessaloniki for Izmir, and from there settled en bloc in the village of Honaz near Denizli.”

- Kappler, Matthias (1996). "Fra religione e lingua/grafia nei Balcani: i musulmani grecofoni (XVIII-XIX sec.) e un dizionario rimato ottomano-greco di Creta." Oriente Moderno. 15. (76): 86. “Accenni alla loro religiosità popolare mistiforme “completano” questo quadro, ridotto, sulla trasmissione culturale di un popolo illetterato ormai scornparso: emigrati in Asia minore dalla fine del secolo scorso, e ancora soggetti allo scambio delle popolazioni del 1923, i “Vallahades”, o meglio i loro discendenti, sono ormai pienamente assimilati agli ambienti turchi di Turchia.”

- Andrews, 1989, p. 103; Friedman

- Hasluck, 1927

References

- Peter Alford Andrews, Rüdiger Benninghaus, eds. Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey Wiesbaden: Reichert, 1989. (cited by Friedman, not seen)

- Frederick de Jong, "The Greek Speaking Muslims of Macedonia: Reflections on Conversion and Ethnicity", pp. 141–148 in Hendrik Boeschoten, ed., De Turcicis Aliisque Rebus: Commentarii Henry Hofman dedicati Utrecht: Institut voor Oosterse Talen en Culturen, 1992. (cited by Friedman, not seen)

- Victor A. Friedman, "The Vlah Minority in Macedonia: Language, Identity, Dialectology, and Standardization", pp. 26–50 in Juhani Nuoluoto, Martti Leiwo, Jussi Halla-aho, eds., University of Chicago Selected Papers in Slavic, Balkan, and Balkan Studies (Slavica Helsingiensa 21). Helsinki: University of Helsinki. 2001. full text

- Margaret M. Hasluck, "The Basil-Cake of the Greek New Year", Folklore 38:2:143 (June 30, 1927) JSTOR

- F. W. Hasluck, 'Christianity and Islam under the Sultans', Oxford, 1929.

- Speros Vryonis, 'Religious Changes and Patterns in the Balkans, 14th-16th Centuries', in Aspects of the Balkans: Continuity and Change (The Hague: 1972).

External links

- N. Sarantakos "Two texts on Vallahades", July 14, 2014. Video, Vallahades in Turkey speaking Greek, 1998 (The 2nd of the two videos).