Våler, Norway

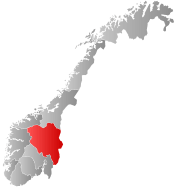

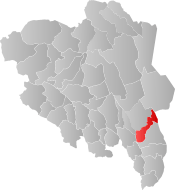

Våler is a municipality in Innlandet (formerly Hedmark) [4] county, Norway. It is part of the traditional region of Solør. The administrative centre of the municipality is the village of Våler.

Våler kommune | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms  Innlandet within Norway | |

Våler within Innlandet | |

| Coordinates: 60°45′12″N 11°53′51″E | |

| Country | Norway |

| County | Innlandet |

| District | Solør |

| Administrative centre | Våler |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2019) | Ola Cato Lie[1] (Sp) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 705 km2 (272 sq mi) |

| • Land | 678 km2 (262 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 158 in Norway |

| Population (2004) | |

| • Total | 3,906 |

| • Rank | 234 in Norway |

| • Density | 6/km2 (20/sq mi) |

| • Change (10 years) | -8.9% |

| Demonym(s) | Vålsokning Vålersokning[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | NO-3419 |

| Official language form | Bokmål[3] |

| Website | www |

.jpg)

General information

Name

The municipality (originally the parish) is named after the old Våler farm (Old Norse: Válir), since the first church was built here. The name is the plural form of váll which means "clearing in the woods".

Coat-of-arms

The coat-of-arms is from modern times. They were granted on 7 August 1987. The arms show a gold-colored winged arrow pointing down on a red background. The arms are based on the legend that in 1022, King Olaf II of Norway (Saint Olaf) shot an arrow and where the arrow hit the ground, he built the church.[5][6]

| Ancestry | Number |

|---|---|

| 45 | |

| 41 | |

| 28 | |

| 26 | |

| 19 |

Geography

The municipality is bordered in the north by Elverum, in the east by Trysil and Sweden, in the south by Åsnes, and in the west by Stange.

The municipality lies in the north end of Solør, and is often referred to as Våler in Solør. Solør is the geographical area that lies between the cities Elverum and Kongsvinger. In the east part of Solør, in the area bordering Sweden lies the area known as Finnskogen.

Agriculture and forestry are the main industries in Våler. With near 90% of the total area covered with forest, Våler is among the larger forested municipalities in Norway. Most of the agricultural areas are found near the river Glomma. The Solør Line runs through the municipality on the east bank of the river.

History

Stone age

It is not known for certain when the first humans arrived in Våler, but it is thought to be at the end of the neolithic era (4000–1800 BC). Tools made of flint have been found that are dated to about 2000 BC. Flint is not natural to the area, indicating it came along trade routes from the south.

The first humans in the deep forests of Våler lived mainly by hunting and fishing. Even though the people around the nearby lake Mjøsa already kept livestock and grew crops, some time passed before the people in Våler settled as farmers.

Pre-Christian times

From about 1000 BC there are findings that indicate settlements in Våler. In the Viking Age, from about 700–1000 AD, Våler became more than just a few settled farms. At one stage in history, Solør was a powerful petty kingdom.

The name Våler comes from the Old Norse word vål, which means “trunks, or stumps (roots) from burnt trees in a clearing.” Names which are variations of vål are common in Norway as the first stage of clearing woodland for cultivation was to burn the trees and undergrowth.[8]

The conversion of Hedemark or Hedmark to Christianity is mentioned in the Heimskringla (The Chronicle of the Kings of Norway) by Snorri Sturluson. According to legend, King Olaf II of Norway (Saint Olaf) went to Våler to convert the heathens to Christianity in 1022 AD. At first there was some resistance, but resistance proved to be futile. The farmers were quickly convinced to convert to Christianity, as in many other areas of Norway. The king decided that they had to build a church, but the locals couldn't agree where to place it. So the king settled the matter in a simple and efficient way. He took his bow, and shot an arrow up in the air and declared that wherever the arrow landed, the church was to be built. The arrow landed in a vål at the banks of the river Glomma. This incident gave name to both the place and the church. (Although later the church was called Mariakirken, which translates to Church of Mary). Våler's Coat-of-arms is illustrating Saint Olaf's arrow.[9]

Medieval period

During the Middle Ages, Våler was just an outpost far from the main travel route. Those few who went through, were either wanderers or pilgrims heading for Saint Olaf's tomb in Nidaros (later Trondheim). One pilgrim's route for Swedish pilgrims lay through Eidskog, Solør and Elverum; Adam of Bremen mentions this route as early as 1070. Along this route, the pilgrims often stopped at the spring at Våler, where legend had it that Saint Olaf had watered his horse; the water was supposed to possess wonderful curative properties.[10]

The Black Death spread through Norway between 1348–1350. We do not know how hard Våler was affected by the plague, but a legend tells that only one boy and one girl survived.

By the 17th century, there was quite a lot of livestock in Våler. As the technology improved, the forestry became more and more important in the forests along the many rivers and lakes in the area.

Finnish immigration

An important part of Våler's and Solør's history, is the immigration and settlement of people from Finland. From the late 16th century they were encouraged by Swedish king Gustav Vasa to settle in the unpopulated areas of Värmland and Solør, along the border between Norway and Sweden. At that time the forests far from the settled areas were of little value, and therefore immigrants could settle in large numbers without coming into conflict with the locals. The Finnish immigration was a result of hunger and turbulent times in Finland. King Gustav Vasa welcomed the immigrants, because he wanted to increase the taxable income from the scarcely populated areas of western Sweden.

The Finns brought with them their unique culture and their way of life. Amongst other things, they imported the agricultural technique, common in Finland and Eastern Sweden, known as svedjebruk or slash-burn agriculture. This involved setting fire to the forest and growing crops on the fertile ash-covered soil. The clearing was initially planted to rye, and then in the second and third year with turnips or cabbages. It then might be grazed for several years before being allowed to return to woodland. In this manner, they periodically moved around and burned down new areas and left their former areas to regrow with forest.[8]

The Finnish language, still has an influence in the area. Many place names and words and expressions in the local dialects derive from the Finnish. The area itself is called Finnskogen, which translates as "The Finnish forest".

Church history

The oldest information known about Mariakirken, is from the 17th century. It was a stave church, and it was by 1686 in very bad condition. Eight hundred years after Saint Olaf, it probably wasn't the same church-building which was built during his reign. Most probably it had been rebuilt at least once, but it must still have been a few hundred years old. It was restored late 17th century, and then lasted another century.

In 1804, the people of Våler asked the King permission to build a new church. The old stave church was yet again in bad condition, and also too small for the growing community. It was permitted by the King, and so the construction of a new church started the same year. The church tower is dated 1805, and the dedication of the new church was 26 June 1806. The old stave church was then torn down. Today, there is a monument where the old church stood.[11]

On 29 May 2009 the Våler church was destroyed by an arson attack, which is suspected to be an act of satanist.[12]

Relics and ornaments

Among the church's relics, the baptismal font of soapstone is probably the oldest. It's from the 12th century, and is still in use. It is in the Romanesque style with interwoven patterns and vined acanthus ornamentation. It was probably carved at one of the stone quarries in the Gudbrandsdal.

A beautiful chalice in Gothic style is an example of excellent 13th century craftsmanship, although it needed restoration in 1717.

A wrought iron ornament, also of the 13th century, which originally decorated the entrance door to the old stave church, is now reused in a 17th-century door placed in one of the church's side entrances.

An even older relic, Olavsspenningen or St. Olav's buckle, is now kept in the collection of ancient relics in Oslo. It is an iron buckle which is forged to look like a withy binding, and legend has it that it was on St. Olav's horse's bridle when St. Olav shot the arrow that determined the location of the Våler church. The buckle apparently fell off, and subsequently was presented as a memorial of the occasion.

A new altar piece was carved in 1697 by Johannes Skraastad (1648–1700) from Vang, Hedmark. The old altar piece from the 17th century, was restored around 1860 and now hangs in the northern end of the church.

Municipality

After 1837, Våler was a part of the municipality of Hof (see formannskapsdistrikt). In 1848, the areas of Åsnes and Våler were separated from Hof as a municipality called Åsnes og Våler. Later, in 1854, Åsnes and Våler became an independent municipalities, after a hard struggle mainly led by parliament member Christian Halvorsen Svenkerud.

References

- "(+) To ganger 10-9 og Lie og Sæterdalen på plass i Våler". www.ostlendingen.no (in Norwegian). 2019-09-30. Retrieved 2019-10-06.

- "Navn på steder og personer: Innbyggjarnamn" (in Norwegian). Språkrådet.

- "Forskrift om målvedtak i kommunar og fylkeskommunar" (in Norwegian). Lovdata.no.

- moderniseringsdepartementet, Kommunal- og (7 July 2017). "Regionreform". Regjeringen.no. Archived from the original on 23 March 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Norske Kommunevåpen (1990). "Nye kommunevåbener i Norden". Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- "Kommunevåpen" (in Norwegian). Våler kommune. Archived from the original on 2007-08-27. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents, by immigration category, country background and percentages of the population". ssb.no. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Sawyer, Birgit; Sawyer, Peter H. (1993). Medieval Scandinavia: from Conversion to Reformation, Circa 800–1500. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-1739-2.

- Sigmund Moren, ed. (1978). Hedmark. Oslo, Norway: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag.

- Stagg, Frank Noel (1956). East Norway and its Frontier. George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Mikal Lundstein, ed. (2004). Jubileumsskrift (Anniversary book). Våler Municipality.

- http://www.roadrunnerrecords.com/blabbermouth.net/news.aspx?mode=Article&newsitemID=121083

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Våler, Innlandet. |

| Look up Våler in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Municipal fact sheet from Statistics Norway

- Municipal website (in Norwegian)