United Nations Security Council Resolution 338

The three-line United Nations Security Council Resolution 338, adopted on October 22, 1973, called for a ceasefire in the Yom Kippur War in accordance with a joint proposal by the United States and the Soviet Union. The resolution stipulated a cease fire to take effect within 12 hours of the adoption of the resolution. The "appropriate auspices" was interpreted to mean American or Soviet rather than UN auspices. This third clause helped to establish the framework for the Geneva Conference (1973) held in December 1973.

| UN Security Council Resolution 338 | |

|---|---|

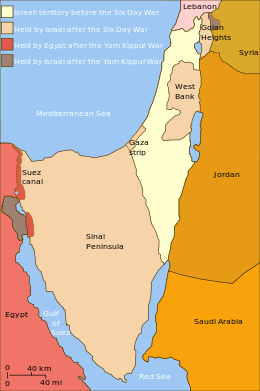

Territorial changes during the Yom Kippur War | |

| Date | 22 October 1973 |

| Meeting no. | 1,747 |

| Code | S/RES/338 (Document) |

| Subject | Cease-Fire in the Middle East |

Voting summary |

|

| Result | Approved |

| Security Council composition | |

Permanent members | |

Non-permanent members | |

The resolution was passed at the 1747th UNSC meeting by 14 votes to none, with one member, the People's Republic of China, not participating in the vote. The fighting continued despite the terms called for by the resolution, brought Resolution 339 which resulted in a cease fire.

The resolution states:

The Security Council,

Calls upon all parties to present fighting to cease all firing and terminate all military activity immediately, no later than 12 hours after the moment of the adoption of this decision, in the positions after the moment of the adoption of this decision, in the positions they now occupy;

Calls upon all parties concerned to start immediately after the cease-fire the implementation of Security Council Resolution 242 (1967) in all of its parts;

Decides that, immediately and concurrently with the cease-fire, negotiations start between the parties concerned under appropriate auspices aimed at establishing a just and durable peace in the Middle East.

Binding or non-binding issue

The alleged importance of resolution 338 in the Arab–Israeli conflict supposedly stems from the word "decides" in clause 3 which is held to make resolution 242 binding. However the decision in clause 3 does not relate to resolution 242, but rather to the need to begin negotiations on a just and durable peace in the Middle East that led to the Geneva Conference which Syria did not attend.

The argument continues; Article 25 of the United Nations Charter says that UN members "agree to accept and carry out the decisions of the Security Council". It is generally accepted that Security Council resolutions adopted according to Chapter VII of the UN Charter in the exercise of its primary responsibility for the maintenance of international peace in accordance with the UN Charter are binding upon the member states.[1][2]

Scholars applying this doctrine on the resolution assert that the use of the word "decide" makes it a "decision" of the Council, thus invoking the binding nature of article 25.[3] The legal force added to Resolution 242 by this resolution is the reason for the otherwise puzzling fact that SC 242 and the otherwise seemingly superfluous and superannuated Resolution 338 are always referred to together in legal documents relating to the conflict.

The more obvious need for the use of Resolution 338 is that it requires all parties to cease fire and states when that should occur, without which Resolution 242 can't be accomplished.

Some scholars have advanced the position that the resolution was passed as a non-binding Chapter VI recommendation.[4][5] Other commentators assert that it probably was passed as a binding Chapter VII resolution.[6] The resolution contains reference to neither Chapter VI nor Chapter VII.

Adoption of the Resolution

Egypt and Israel accepted on October 22 Resolution conditions. Syria, Iraq, and Jordan rejected the Resolution.[7][8]

Execution requirements of the Resolution by Egypt and Israel

An October 22 United Nations-brokered ceasefire quickly unraveled, with each side blaming the other for the breach.[9]

- According to some sources, Egypt broke the cease-fire first:

The cease fire soon violated because Egypt's Third Army Corps tried to break free of the Israeli Army's encirclement. The Egyptian action and the arrival of more Soviet equipment to Cairo permitted Israel to tighten its grip on the Egyptians[10]

- According to other sources, Israel broke the cease-fire first:

On October 22 the superpowers brokered UN Security Council Resolution 338. It provided the legal basis for ending the war, calling for a cease-fire to be in place within twelve hours, implementation of Resolution 242 'in all its parts' and negotiations between the parties. This marked the first occasion the Soviets had endorsed direct negotiations between the Arabs and Israel without conditions or qualifications. Golda Meir, the Israeli Ptine Minister, who was not consulted, was offended by this fait accompli, though she had little option but to comply.

Nevertheless, Meir was determined to gain the maximum strategic advantage before the final curtain came down on the conflict. Given the entanglement of the Egyptian and Israeli armies, the temptation was too great for the Israelis to resist. After a final push in the Sinai expelled the Egyptians, Meir gave the order to cross the Canal.

Israel's refusal to stop fighting after a United Nations cease-fire was in place on October 22 nearly involved the Soviet Union in the military confrontation.[11] [12][13]

Arab–Israeli peace diplomacy and treaties

- Faisal–Weizmann Agreement (1919)

- Paris Peace Conference, 1919

- 1949 Armistice Agreements

- Camp David Accords (1978)

- Egypt–Israel Peace Treaty (1979)

- Madrid Conference of 1991

- Oslo Accords (1993)

- Israel–Jordan peace treaty (1994)

- Camp David 2000 Summit

- Israeli–Palestinian peace process

- Projects working for peace among Israelis and Arabs

- List of Middle East peace proposals

- International law and the Arab–Israeli conflict

See also

References

- Higgins, Rosalyn, The Advisory Opinion on Namibia: Which UN Resolutions Are Binding Under Article 25 of the Charter?, in 21 Int'l & Comp. L.Q. 286 1972 pp. 270–266, pp. 285–286

- "Legal Consequences for States of the continued presence of South Africa in Namibia, notwithstanding Security Council Resolution 276 (1970)" in [1971] I.C.J. Reports pp. 4–345, pp 52–53

- Rostow, Eugene V. "The Illegality of the Arab Attack on Israel of October 6, 1973." The American Journal of International law, 69(2), 1975, pp. 272–289.

- Adler, Gerald M., Israel and Iraq: United Nations Double Standards – UN Charter Article 25 and Chapters VI and VII (2003)

- Einhorn, Talia, "The Status of Palestine/Land of Israel and Its Settlement Under Public International Law" in Nativ Online No.1 Dec. (2003)

- Kattan, Victor,Israel, Hezbollah, and the use and abuse of self-defence in international law (2006)

- Electronic Jewish Encyclopedia http://www.eleven.co.il/article/10954

- 232. Memorandum of Conversation, Tel Aviv, October 22, 1973, 2:30–4:00 p.m // Arab–Israeli Crisis and War, 1973, р. 662–666

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-01. Retrieved 2013-03-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Chronological History of U.S. Foreign Relations by Lester H. Brune and Richard Dean Burns (Nov 22, 2002)

- [Academic Journal.Stephens, Elizabeth. "Caught on the hop: the Yom Kippur War: Elizabeth Stephens examines how thirty-five years ago this month the surprise invasion of Israel by Egypt and its allies started the process that led to Camp David." History Today 58.10 (2008): 44+. World History In Context. Web. 1 Mar. 2013.]

- "The Office of the Historian.Arab-Israeli War 1973". Archived from the original on 2013-03-09. Retrieved 2013-03-22.

- The National Security Archive .The October War and U.S. Policy.