Thomond

Thomond (Classical Irish: Tuadhmhumhain; Modern Irish: Tuamhain), also known as the kingdom of Limerick,[2] was a kingdom of Gaelic Ireland, associated geographically with present-day County Clare and County Limerick, as well as parts of County Tipperary around Nenagh and its hinterland. The kingdom represented the core homeland of the Dál gCais people, although there were other Gaels in the area such as the Éile and Eóganachta, and even the Norse of Limerick. It existed from the collapse of the Kingdom of Munster in the 12th century as competition between the Ó Briain and the Mac Cárthaigh led to the schism between Thomond ("North Munster") and Desmond ("South Munster"). It continued to exist outside of the Anglo-Norman controlled Lordship of Ireland until the 16th century.

Thomond Tuamhain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1118–1543 | |||||||||

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

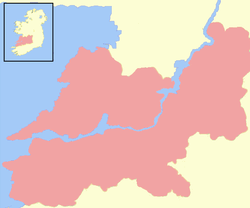

Thomond before the Norman invasion of Ireland | |||||||||

| Capital | Clonroad | ||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Irish, Early Modern Irish, Latin | ||||||||

| Religion | Catholic Christianity Gaelic Polytheism | ||||||||

| Government | Tanistry | ||||||||

| Rí | |||||||||

• 1118–1142 | Conchobhar Ó Briain | ||||||||

• 1539–1543 | Murchadh Carrach Ó Briain | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1118 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1543 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The exact origin of Thomond, originally as an internal part of Munster, is debated. It is generally held that the Déisi Muman pushed north-west starting from the 5th to the early 8th century, taking the area from the Uí Fiachrach Aidhne of the Connachta. Eventually, the Dál gCais rose to power in all of Munster, to the detriment of the Eóganachta. The person most famously associated with this is Brian Boru, High King of Ireland, best known for his feats at the Battle of Clontarf. Four generations down the line and after providing three more High Kings, the Dál gCais were unable to hold onto all of Munster and so Thomond came into being as a separate entity.

Between the mid-12th and late 13th century, when much of Ireland came under direct English control and/or settlement, Thomond too came into the Anglo-Irish sphere. The de Clare family established a colony at Bunratty, while the Butler and FitzGerald families also made inroads. However, from the time of the Battle of Dysert O'Dea, Thomond was restored as a kingdom, with its rulers reinstating Limerick within their overrule. Not until the 1540s did the ruling O'Brien dynasty accommodate with English rule.

Geography

County Clare was sometimes known as County Thomond in the period immediately after its creation from the District of Thomond.[3]

In 1841, an estimation of the extent of the kingdom was undertaken by John O'Donovan and Eugene Curry[4]

"The principality of Thomond, generally called the Country of the Dal-Cais, comprised the entire of the present Co. of Clare, the Parishes of Iniscaltra and Clonrush in the County of Galway, the entire of Ely O'Carroll, the Baronies of Ikerrin, Upper and Lower Ormond, Owney and Arra, and somewhat more than the western half of the Barony of Clanwilliam in the County of Tipperary; the Baronies of Owenybeg, Coonagh and Clanwilliam, and the eastern halves of the Baronies of Small County and Coshlea in the County of Limerick."[5]

History

Creation from Munster

The entire Province of Munster was under the control of the O'Brien (Ua Briain) clan under the leadership of Toirrdelbach Ua Briain and his son Muirchertach from 1072-1114. Their capital was located in Limerick. In a bid to secure the High Kingship of Ireland for the clan, Muirchertach encouraged ecclesiastical reform in 1111 with the creation of territorial dioceses over the entire island. They had support for their bid from several foreign connections including the Norwegian king Magnus Bareleg and the Anglo-Norman baron Arnulf de Montgomery, who were both united to the clan through marriage in 1102.[6]

Their claim to the High Kingship was countered by the O'Neill (Uí Néill) clan in Ulster under the leadership of Domnall MacLochlainn of Ailech. Though Muirchertach campaigned hard in the north, he was unable to obtain the submission of Ailech. When he fell ill in 1114 he was deposed by his brother Diarmait. Muirchertach did briefly regain power, but after his death in 1119 his brother's sons took control of the clan.[6]

MacLochlainn's plans to restore the High Kingship to the north was thwarted by his ally Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair of Connacht who formed an alliance with the O'Brien's. In 1118 Conchobair partitioned Munster between the sons of Diarmait and Tagh Mac Carthaig. The northern section of the province became the O'Brien Kingdom of Thomond (Tuadh Mhumhain "North Munster") and the southern became the Mac Carthaigh Kingdom of Desmond (Deas Mhumhain "South Munster").[6]

Normans and Civil Wars

From the 12th to the 14th centuries, the Norman invasion and their multiple attempts to take Thomond from the Gaels was the main challenge to the realm. The picture was complicated by rival branches of the Ó Briain trying to ally with various different Normans to enforce their own line as reigning over Thomond. At the time of the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169, Domhnall Mór Ó Briain was king of Thomond. Domhnall was a man of realpolitik; his main concern was upholding his position in Thomond and was not against collaborating with Strongbow and others against rival Gaelic kingdoms such as Ossory, Desmond and Connacht.[7] Domhnall even acknowledged Henry II as Lord of Ireland at Cashel in 1171, but a mere two years later when Plantagenet tried to grant Thomond to Philip de Braose this situation was overturned. The Dál gCais defeated a Norman army at the Battle of Thurles in 1174, where over 1700 Normans were killed. The following year when Raymond le Gros captured Limerick through a naval invasion, Domhnall re-took it and burned it rather than have it in foreign hands.[nb 1] The twenty years after that for the Gaels of Thomond were more secure.

After the death of Domhnall Mór a period of destructive feuding among his offspring caused a great territorial decline in Thomond. The brothers Muircheartach Finn Ó Briain and Conchobhar Ruadh Ó Briain fought with each other, seeing Muircheartach's reign interrupted between 1198-1203. Muirchertach himself was blinded by the Normans in 1208 and was soon forced into abdication due to no longer being righdamhna. Donnchadh Cairprech Ó Briain had to deal with dissent from the Mac Con Mara and Ó Coinn against his rule, so brought in the Laigin's Mac Gormáin as his standard bearers. Donnchadh also enlisted the support of the de Burgh and other Normans in this fight, which came at a costly price; Limerick and lands surrounding it in what would later become County Limerick and County Tipperary.[nb 2] Under pressure from the Butlers, Thomond was now not too different to what would become County Clare, protected by the River Shannon. Donnchadh moved his capital to Clonroad.

The Normans advance continued during the reign of Conchobhar na Suidaine Ó Briain, as Henry III "granted" lands to Robert de Muscregos and John Fitzgeoffrey.[7] Of the two de Muscregos was most active, constructing Clare Castle and Bunratty Castle with a colony. The precedent for Thomond was very dangerous as, should much more land have been taken, the realm would have no longer existed. Conchobhar and his fiery son Tadhg Cael Uisce Ó Briain took up arms and slaughtered many of the Norman settler-colonists in 1257.[7] The following year, the Gaelic chiefs from all over Ireland had resolved to form an anti-Norman pact and met at Cael Uisce, near Lough Erne to discuss terms. They planned to resurrect the High Kingship of Ireland, with most supporting Brian Ó Néill as the choice. Tadhg was proud and stubborn, declaring his father should be High King; the Dál gCais thus did not take part in the Battle of Druim Dearg, which the Gaels lost, damaging the reputation of Thomond as a consequence.

Brian Ruadh Ó Briain kept the pressure up by burning Clare Castle and forcing the de Muscregos' to flee to Wales, but he had troubles from his own countrymen. The Mac Con Mara, Ó Deághaidh and Mac Gormáin clans supported his nephew Toirdelbach Ó Briain, a son of Tadhg Cael Uisce, for the kingship instead and revolted. Seeing an opportunity, Edward II offered Thomond to Thomas de Clare if he could take advantage of the Ó Briain feud. The events which followed have passed down to history as the Cathreim Thoirdhealbhaigh. After Brian briefly regained Clonroad with de Clare's help, Toirdelbach arrived with support from Galway in the form of the de Burghs and once again took control in 1277. Brian was executed by his "ally" at Bunratty, but de Clare was soon reconciled with his son Donnchadh mac Brian Ó Briain and supported him against Toirdelbach. The feud continued until Donnchadh drowned at a party on Islandmagrath, on the River Fergus. With Toirdelbach now undisputed king, the Mac Con Mara were able to hound de Clare.

The conflict between the two lines continued into the next generation between Donnchadh mac Toirdelbach Ó Briain (backed by William Liath de Burgh) and Diarmuid Cléirech Ó Briain (backed by Richard de Clare). There was military success at Bunratty in 1311 for Diarmuid and his cousin Donnchadh was killed at Corcomroe. Following this, Clann Tadhg's leader was Muircheartach mac Toirdelbach Ó Briain and after Diarmuid's "sudden" death, Clann Briain Ruadh's leader became Donnchadh mac Domhnall Ó Briain. The Bruce Wars in Ireland added an unpredictable element and saw some surprising ad hoc alliances come into play. Donnchadh elected to support Edward the Bruce, which made his patron de Clare an enemy. Muircheartach who now reigned supreme in Thomond, due to his connection to de Burgh, was nominally on the side of the Lordship of Ireland. The cousins fought at the Second Battle of Athenry. Muircheartach's brother Diarmuid mac Toirdelbach Ó Briain managed to destroy Donnchadh and most of Clann Briain Ruadh's supporters at the Battle of Corcomroe in 1317. The end of the de Clares and Norman territorial claims in Thomond came the following year at the Battle of Dysert O'Dea, due largely to Conchobhar Ó Deághaidh, whose tactics secured a famous victory.[8]

Unity and Resurgence

The last successful attempt by a Norman to play divide and conquer within the Thomond kingship was the case of Maurice FitzGerald, Earl of Desmond. A very powerful man, he was constantly rumoured during his life to have wanted to make himself King of Ireland. He successfully sponsored Brian Bán Ó Briain in overthrowing Diarmuid from Clan Tadhg during 1343-1350, but equally decisive was the sides taken by Mac Con Mara, leading to Diarmuid's restoration. With the exception of a failed Norman attempt to reconstruct Bunratty Castle by Thomas de Rokeby from 1353-1355, the Norman settler-colonialist project in Thomond was at an end until the submission of the Ó Briain in the 16th century. The Norman Lordship was weakened by the Bruce Wars of 1315-1318, the Black Death of 1349-1350 (which disproportionally hit Norman controlled towns) and besides that English forces were more invested with the Hundred Years' War in France and their own internal conflict the Wars of the Roses to focus too much on Ireland. All of these factors allowed for a 15th-century Gaelic resurgence, not only in Thomond but across a significant part of Ireland outside of the Pale.

.jpg)

Brian Bán was the last of Clann Briain Ruadh to hold the kingship and from 1350 onwards, Clann Tadhg held sway. Mathghamhain Maonmhaighe Ó Briain came to power before the death of his uncle Diarmuid and he was named as such because he spent time as a foster child in Máenmaige. His succession was disputed by his uncle and brother; Toirdelbhach Maol Ó Briain and Brian Sreamhach Ó Briain. Of the two Brian Sreamhach gained the upper hand and when his uncle tried to enlist the help of the Earl of Desmond to wrestle back the realm, Brian thoroughly routed them at Croom in a key military success. This had the added benefit of winning back Limerick for Thomond and Sioda Cam Mac Con Mara was placed in the city as a warden in 1369. The friendship with the de Burghs of Galway was maintained by Brian and when Richard II was at Waterford in 1399, he paid nominal homage and was well received. Thomond was now in such a position that Conchobhar mac Mathghamhna Ó Briain's twenty six-year reign was marked as a time of peace and plenty.

The years 1426-1459 were marked by a succession of three sons of Brian Sreamhach reigning; Tadhg an Glemore Ó Briain, Mathghamhain Dall Ó Briain and Toirdelbhach Bóg Ó Briain. During this time, Mathghamhain Dall was deposed by his brother Toirdelbhach with the familiar military assistance of the de Burghs (whom he had formed a marriage alliance with). Greater things were to come from the ascent of Toirdelbhach's son Tadhg an Chomhaid Ó Briain. From Inchiquin, Tadhg took advantage of the Wars of the Roses, forming an alliance with the Ó Néill in 1464. He managed to ride south through Desmond (the rest of the old Munster) and enforce the cíos dubh on the Anglo-Normans. This was a kind of Gaelic pizzo which Tadgh's great-grandfather Mathghamhain Maonmhaighe had first been able to enforce as a price of protection. His military prowess was such that the Earl of Desmond was forced to give back to Thomond what would later become County Limerick. Mac Fhirbhisigh hints that the men of Leinster planned to raise Tadhg to the High Kingship of Ireland before his death and claims he was the greatest Ó Briain since Brian Bóruma himself.

Thomond was wealthy in the 15th century; Domhnall Mac Gormáin (died 1484) was described as the richest man in Ireland in terms of live stock. During the reign of Conchobhar na Srona Ó Briain, Thomond maintained alliances with the Mac William Uachtar of Clanricarde and the Butlers. In the latter case, they were opposing the Kildare FitzGeralds, earning the ire of Gerald FitzGerald, Earl of Kildare who had earned the favour of the new Tudor king Henry VII as Lord Deputy of Ireland. Despite Kildare's fearsome reputation, Conchobhar met him in battle at Ballyhickey, near Quin, in 1496 and was successful in turning him back. Toirdelbhach Donn Ó Briain as part of his pact with Ulick Fionn Burke took part in the Battle of Knockdoe in 1504; along with the Mac Con Mara and Ó Briain Ara; against the Earl of Kildare, which they lost. The struggle had been started by a feud between de Burgh and the Ui Maine. Ó Briain later defeated Kildare at Moin na Brathair, near Limerick. Thomond intended to support the Ó Néill against the Ó Domhnaill in a northern feud, but by the time Ó Briain arrived, it was over. Toirdelbhach's life came to an end trying to defend the Ó Cearbhaill of Éile from the Earl of Ormond at Camus, near Cashel; he died "by the shot of a ball."

Downfall of the Realm

The downfall of Thomond occurred in the 16th century. The series of events leading up to it, were set into process by the rebellion of FitzGerald family member, the Earl of Kildare, Silken Thomas. In 1534, a rumour had spread that his father, the Lord Deputy of Ireland, had been executed in England on the orders of king Henry VIII and that the same fate was planned for him and his uncles. Under this impression, Thomas threw off his offices in the Kingdom of Ireland and rose up in rebellion. He took refuge with the Ó Cearbhaill of Éile and then with Conchobhar mac Toirdhealbaig Ó Briain at Clonroad, Ennis. In hot pursuit, at the head of an army, was Lord Leonard Grey, who destroyed the Killaloe Bridge, which had the result of isolating Thomond from the rest of Ireland and also attacked the Dál gCais east of the River Shannon.

Although the Silken Thomas issue was resolved by late 1535, Thomond had marked itself out by providing refuge to enemies of the Crown of England in Ireland. The English forces had in turn enlisted the services of Conchobhar's own son Donnchadh Ó Briain who had cemented an alliance with the Butler family by marrying the daughter of the Earl of Ormond. According to Butler, Donnchadh pledged to help them conquer Thomond, aid English colonisation, adopt English laws and help them take over Carrigogunnell Castle. This castle was a symbol of Gaelic defiance, as it had remained out of Anglo-Norman hands for over 200 years. When the castle was attacked by Grey, it surrendered due to Donnchadh. With the loss of east Thomond and the destruction of O'Brien's Bridge, Thomond was in a lot of trouble. Conchobhar, along with loyal supporters such as the Mac Con Mara, continued to fight on and managed to conclude a truce with Grey in 1537.

Conchobhar was succeeded on his death by his brother Murchadh Carrach Ó Briain, a man who initially attempted to assist Conn Bacach Ó Néill in the defence of Tír Eoghain but had come to see the futility of his opposition and agreed to surrender and regrant to the Tudor state. The Parliament of the Kingdom of Ireland was called to Limerick in 1542 by Lord Deputy Anthony St. Leger regarding the terms of submission of Murchadh Carrach Ó Briain and Sioda Mac Con Mara. Becoming members of the Peerage of Ireland and converting to the Anglican Church, Murchadh was made Earl of Thomond and Donnchadh also Baron Ibrackan. Dissent took place in the form of Donchadh's brother Domhnall Ó Briain (and his ally Tadhg Ó Briain) who claimed to have been inaugurated Chief of the Ó Briain according to the Gaelic fashion in 1553. This was in opposition to his nephew the Earl, Conchobhar Groibleach Ó Briain. Tied into English political rivalries, Conchobhar had the support of the Earl of Sussex but was not able to decisively defeat his uncle, indeed Domhnall scored a victory at the Battle of Spancel Hill in 1559. The discord dragged on and Thomond was under the martial law of William Drury as late as 1577. The issues pertaining to tax and land were finalised at the Composition of Thomond in 1585.

Diocese of Killaloe

The religion which predominated at an official level in Thomond was Catholic Christianity. The territory of Thomond was associated with the Diocese of Killaloe under the Bishop of Killaloe, which had been formed in 1111 at the Synod of Ráth Breasail, seven years before Thomond broke fully from the Kingdom of Munster. Dál gCais influence over the Bishop of Limerick differed from time to time, with Norman influence also being part of the picture. At the Synod of Kells in 1152, three more sees in Thomond were created in the form of the Diocese of Kilfenora, the Diocese of Roscrea and the Diocese of Scattery Island. Roscrea was re-merged with Killaloe in 1168 and Scattery Island followed in 1189. The latter was re-created briefly during the 14th century before once again being merged back with Killaloe.

Some of the Bishops of Killaloe attended Ecumenical Councils of the Catholic Church in Rome; this includes Constantín Ó Briain who participated in the Third Lateran Council and Conchobhar Ó hÉanna who was at the Fourth Lateran Council. Religious orders were present in Thomond and had establishments founded by them under the patronage of Kings of Thomond. This includes; the Canons Regular of the Augustinians at Canon Island Abbey, Clare Abbey, Inchicronan Priory, Killone Abbey and Limerick Priory, the Cistercians at Holy Cross Abbey, Corcomroe Abbey, Kilcooly Abbey and Monasteranenagh Abbey, the Franciscans at Ennis Abbey, Galbally Friary and Quin Abbey (the latter of which became a formidable college)[9] and the Dominicans at Limerick Blackfriars. There were also many monasteries which predated Thomond such as Inis Cealtra Monastery, Scattery Island Monastery and Dysert O'Dea Monastery. Both St. Flannan's Cathedral in Killaloe and St. Mary's Cathedral in Limerick can be traced to Domhnall Mór Ó Briain.

Monarchs

Annalistic references

See Annals of Inisfallen (AI).

- AI927.3 Repose of Mael Corguis Ua Conaill, bishop of Tuad Mumu.

- AI953.3 Repose of Diarmait son of Aicher, bishop of Tuad Mumu.

- AI963.4 A slaughter of the Tuad Mumu on the Sinann, and they abandoned their vessels and were drowned.

- AI1018.2 Ciarmacán Ua Maíl Chaisil, bishop of Tuadmutnu, rested in Christ.

See also

Notes

- The psychological effect that this gesture had on the Normans is evident from when Philip de Braose, Robert FitzStephen and Miles de Cogan rode out to take Limerick city and fled in a great panic upon seeing it in flames. Realising that Domhnall Mór and the Dál gCais would sooner burn it to the ground than have anyone but themselves rule it.

- The Normans also attempted to takeover the key religious post of Bishop of Killaloe. Geoffrey de Marisco promoted his nephew Robert Travers into the post in 1215, with support of the English monarchy. The Gaels disputed his election to Pope Honorius III and in this case Rome took their side, deposing Travers in 1221 in favour of Domhnall Ó hÉanna.

References

- "O'Brien (No. 1.) King of Thomond". LibraryIreland.com. Retrieved on 26 July 2009.

- Duffy, Sean. Medieval Ireland An Encyclopedia. p. 58.

- Luminarium Encyclopedia: Biography of Sir Henry Sidney (1529–1586).

- John O'Donovan and Eugene Curry, "Ordnance Survey Letters", Part II. Letters and Extracts relative to Ancient Territories of Thomond, 1841

- Clare library, retrieved 21 March 2012.

- Byrne, F.J. Cosgrove, Art (ed.). A New History of Ireland II:The trembling sod: Ireland in 1169. Royal Irish Academy. ISBN 9780199539703.

- "The Normans in Thomond". Joe Power. 21 July 2015.

- "The Battle of Dysert O'Dea and the Gaelic Resurgence in Thomond". Katharine Simms. 21 July 2015.

- "Killaloe". Catholic Encyclopedia. 28 November 2015.

Bibliography

- Bradshaw, Brendan (1993). Representing Ireland: Literature and the Origins of Conflict, 1534-1660. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521416345.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Byrne, Francis J. (1973). Irish Kings and High Kings. Four Courts Press. ISBN 1851821961.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Canny, Nicholas (2001). Making Ireland British, 1580-1650. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199259052.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Connolly, S. J. (2009). Contested Island: Ireland 1460-1630. OUP Oxford. ISBN 0199563713.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ellis, Peter Berresford (2002). Erin's Blood Royal: The Gaelic Noble Dynasties of Ireland. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0312230494.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frost, James (1893). The History and Topography of the County of Clare: From the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the 18th Century. Nabu Press. ISBN 1147185581.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gleeson, Dermot Florence (1962). A History of the Diocese of Killaloe. M. H. Gill and Son Ltd.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnson Westropp, Thomas (1890). Notes on the Sheriffs of County Clare, 1570-1700. Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacNamara, Nottidge Charles (1893). The Story of an Irish Sept: Their Character and Struggle to Maintain Their Lands in Clare. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1167011775.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ó Muraíle, Nollaig (2004). The Great Book of Irish Genealogies. De Burca Books. ISBN 0946130361.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, Patrick (1893). History of Clare and the Dalcassian clans of Tipperary, Limerick and Galway. Nabu Press. ISBN 1177212854.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)