Irish Royal Army

The Irish Royal Army or Irish establishment refers to the British crown armies stationed in the Kingdom of Ireland between 1542 and 1801. The regiments on the establishment were placed on the British establishment following the Act of Union, although some roles continued to exist separately.

Origins

The origins of the Irish Royal Army were in the traditional royal garrisons of the old Lordship of Ireland. Numbers were low during peacetime, and during the sixteenth century the force would be supplemented by assembling militia in The Pale and the raising of troops by loyal Gaelic chieftains during emergencies. It was financed by votes in the Irish Parliament, although this was sometimes supplemented by subsidies sent over from London. The principal task of the Army was to defend Ireland from internal disorder and invasion by foreign powers.[1]

The Irish security situation had come under strain during the rebellion of Thomas FitzGerald, 10th Earl of Kildare in the 1530s.[2] The Fitzgerald family had traditionally been the leading Anglo-Irish lords in the country, serving as Lord Lieutenants. Their rebellion exposed the weakness of Henry VIII's forces in the Lordship of Ireland, with the rebels securing large gains and launching a Siege of Dublin.

Tudor era

In 1542 the Kingdom of Ireland was formally established and Henry VIII declared King. It accompanied a major policy to bring the whole island under control of Dublin, partly through the surrender and regrant offers to major Gaelic leaders. It was intended that traditional Gaelic feuds and succession disputes would be replaced by a more peaceful system of law.

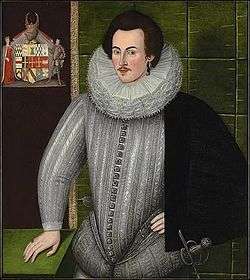

Nicholas Bagenal was appointed Marshal of Ireland with command over the Army, a title he passed to his son Henry Bagenal. Actual command over the forces in charge of suppression the Desmond Rebellion in Munster in the 1580s was given to the Earl of Ormond. Ormond was a prominent Irish leader with good connections at the court of Elizabeth I.

During Tyrone's Rebellion the Army was faced with a major uprising in Ulster. Elements of the Army suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Yellow Ford in 1598 at the hands of the rebel Earl of Tyrone. After receiving substantial reinforcements from England, Lord Mountjoy was able to successfully defeat Tyrone and his Spanish allies at the Siege of Kinsale in 1601. The following year his forces captured Dungannon, the rebel capital. In 1603 Tyrone surrendered to Mountjoy at the Treaty of Mellifont and the Army was dramatically reduced in size. Many of its officers were rewarded with land in exchange for their service.

In 1608 the Army was again called into action following the Burning of Derry which launched O'Doherty's Rebellion. Despite the weakened state of the Army, it won a decisive victory at Kilmacrennan, crushing the uprising.[3] This, along with the Flight of the Earls the previous year, opened the way to a much grander Ulster Plantation. The arrival of large numbers of Protestant settlers changed the balance in the north, presenting new challenges to the Army.

War of the Three Kingdoms

During the Scottish Crisis of the early 1640s, a separate force known as the New Irish Army was raised in 1640-41 which dwarfed the "old" Irish Royal Army in size. Mainly drawn from the Catholic Gaelic inhabitants of Ulster, and mustered at Carrickfergus, it was intended to take part in a landing on the coast of Scotland. However it was rumoured that Charles I planned to lead the New Irish Royal Army against his enemies in the English Parliament, in the months before the outbreak of the English Civil War. When the Irish Rebellion of 1641 broke out, the traditional Irish Royal Army was too small in size to cope. Many soldiers of the New Irish Royal Army joined the rebels, and soon controlled large swathes of Ireland.

Large numbers of reinforcements were shipped over from England in 1642, known as the "English Army for Ireland",[4] to support the Irish royalists. Scotland despatched a separate force to Ulster. Irish Protestants in counties Londonderry and Donegal raised their own force known as the Laggan Army, which was nominally under the command of the Crown, but largely acted independently. The situation was further complicated by the fact that the Irish Confederacy continued to insist upon their loyalty to the Crown, and stated that King Charles had endorsed the rebellion.

Under its commander the Duke of Ormonde, the Irish Royal Army engaged in a complex mixture of fighting and truces as it sought to end the rebellion. It was Ormonde's hope that a peace treaty in Ireland would allow the various forces to unite and cross to England to assist Charles in the English Civil War. By 1647 it was clear that this was not going to take place and Ormonde handed over Dublin to the English Parliamentary forces.

Charles I was executed in 1649 and Ormonde returned to Ireland with orders from his successor Charles II to form an alliance amongst the various forces, Catholic and Protestant, opposed to the new English Republic. Ormonde launched an attempt to capture Dublin but suffered a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Rathmines. A large expedition under Oliver Cromwell then landed and won a series of victories that brought the whole of Ireland under their control. The remnants of the Royalist Irish Army served in exile under Charles II, while Ireland was garrisoned by a mixed force of English republican troops and Irish Protestants until 1660.

Restoration

The

In 1660 Charles was restored to the Irish throne. The Irish Royal Army was reformed by the returning Ormonde, with gradual attempts to purge it of the remaining supporters of the old Cromwell regime. It numbered 5,000 infantry and 2,500 cavalry, considerably bigger than it had been before the rebellion, and was the largest armed force available to Charles in the British Isles. In 1662 Ormonde raised a regiment of Irish Guards to provide added security. The cost of the Army that year was £146,000.[5]

In 1680 the Royal Hospital Kilmainham was built for the welfare of soldiers.[6]

During this period a major fear was a revival of republicanism amongst Ireland's Protestants, and extra troops were stationed around Cork and particularly in Ulster to guard against this. This strategy was broadly successful and there was no equivalent Irish rising to the 1685 Monmouth and Argyll rebellions.[7]

Williamite War

Following the accession of James II in 1685, the newly appointed Viceroy, Richard Talbot, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell conducted a purge of Protestant officers of the Army replacing them with Catholics who had previously been generally excluded because of the Penal Laws.[8] He also rapidly expanded the Army in size. Elements of the Irish Royal Army fought on both sides during the Williamite War that followed, although primarily for James II.

Irish Protestants unhappy with the rule of King James launched a rebellion in 1689, forming the Army of the North and declaring William III to be King. Although the Irish Royal Army was able to secure control over most of the island, Derry held out. A major Williamite expeditionary force landed and captured Carrickfergus. It consisted of many newly formed regiments commanded by Protestant officers recently dismissed from the Irish Royal Army by Tyrconnell, as well as large foreign contingents. However their advance on Dublin faltered, and thousands died of sickness at Dundalk Camp.

In July 1690 the Battle of the Boyne was fought, leading to the defeat of the Jacobite Army and their French Allies. William III personally led his troops to victory, capturing Dublin in the wake of the battle. However he was beaten back by the Jacobites at the Siege of Limerick in September.

The following year the bloodiest battle in Irish history was fought at Aughrim with the Irish Royal Army again defeated by the international force assembled against it.

Led by Patrick Sarsfield the Catholic regiments went into exile following their defeat at the Second Siege of Limerick and served in Continental European Armies as "Wild Geese". A separate Irish Brigade had been formed in 1689–90 for service in the French Army. The two forces were amalgamated in 1698 but continued the traditions of the old Irish Royal Army, and remained committed to the restoration of the Jacobites. They continued to wear the red coat of the Irish Royal Army, leading to occasional confusion when they were fighting the British Army.[9] Catholics, formally denied the right to enlist in the Irish Royal Army at home, served as Wild Geese in significant numbers.

William reformed the Irish Royal Army, using it as a source of recruits for his international coalition during the Nine Years' War, and deploying it across Ireland as a garrison to prevent any potential Jacobite rising. Following the Treaty of Ryswick, William planned to maintain a much larger standing army in Ireland but he was forced by Parliamentary pressure to reduce this to 12,000.[10]

Eighteenth century

For much of the eighteenth century, the Irish Royal Army formed a strategic reserve for the British forces serving around the globe. Regiments would often be transferred to Ireland when they wished to recruit up to full strength. Although Catholics continued to be officially excluded from the Army throughout the era, many served the House of Hanover.

Jacobite threat

The Army continued to support the civil powers in the events of disturbances, such as the Dublin election riot in 1713. It also remained vigilant against the prospects of a Jacobite rebellion to restore the Stuarts to the throne, widespread amongst many Catholic followers of the exiled Duke of Ormonde. Contrary to expectations, a major rising did not place in Ireland following the Hanoverian Succession of 1714. Regiments from Ireland were sent over to Scotland to support the suppression of the Jacobite rising of 1715.[11]

A large network of barracks were constructed across the island, considerably ahead of many other regions where it was still usual to quarter soldiers in private houses. The Army was increased in size to 18,000.

Ireland was considered a potential target of invasion by France during the Seven Years' War. In 1760 the Irish Royal Army was called out following a French landing at Carrickfergus. However the enemy withdrew before a major battle took place.

French and Indian war

The British government drew on regiments on the Irish establishment for the Expedition to Fort Duquesne at the opening stages of the French and Indian war. The 44th and 48th foot were quickly dispatched from Ireland and suffered heavy casualties at the disastrous engagement at Monongahela. Both regiments continued to serve throughout the war taking part in the more successful expedition against Havana before returning home in 1763 for service again in Ireland.[12]

American War of Independence

Following the outbreak of rebellion in Britain's Thirteen Colonies in 1775, Ireland provided large numbers of recruits to the expanded British Army. Following a vote in the Irish Parliament, it was agreed that a number of Irish Royal Army regiments be allowed to serve in America. This led to concerns that Ireland was not properly defended once France entered the war in 1778, having sent so many soldiers abroad. A spontaneous movement established the Irish Volunteers, committed to the defence of the island against invasion. Despite this, the Volunteers rapidly emerged as a political movement demanding greater powers be granted to Ireland by London, which eventually led to the Constitution of 1782. Amongst its many measures, this gave the Irish Parliament greater control over its own armed forces.

Rebellion of 1798

In the 1790s the Irish Royal Army was described as "not fit for purpose". This came at a time of growing support for the republican ideas of the French Revolution, amidst fears of the revolutionary spirit spreading to Britain and Ireland.

Amalgamation

The Irish Royal Army was amalgamated into the British Army following the Acts of Union 1800. By this stage the traditional ban on Irish Catholics serving in the army had been completely removed, and they began to supply a growing portion of troops.

Notes

- Bartlett & Jeffrey 1996 p.248

- Bartlett & Jeffrey 1996 pp.116–135

- McCavitt p.136-48

- Ryder, Ian English Army for Ireland 1642; Partizan Press 1987, ISBN 978-0946525294

- Childs. Army of Charles II p.204

- Bartlett & Jeffrey 1996 pp.212–13

- Bartlett & Jeffrey p.235

- Childs 1980, pp. 56–79

- McNally p.83

- Childs 1987, p.194-202

- Reid p.19-20

- "48th (Northamptonshire) Regiment of Foot: locations". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 10 November 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

References

- Bartlett, Thomas & Jeffrey, Keith (1996). A Military History of Ireland. Cambridge University Press.

- Childs, John. Army of Charles II. Routledge, 2013.

- Childs, John (1980). The Army, James II and the Glorious Revolution. Manchester University Press.

- Childs, John (1987). The British Army of William III, 1688–1702. Manchester University Press.

- McNally, Michael. Fontenoy 1745: Cumberland's bloody defeat. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017.

- Reid, Stuart Sheriffmuir 1715. Frontline Books, 2014.

Further reading

- McCavitt, John. The Flight of the Earls. Gill & MacMillan, 2002.