Truck driver

A truck driver (commonly referred to as a trucker, teamster or driver in the United States and Canada; a truckie in Australia and New Zealand;[1] a lorry driver, or driver in Ireland, the United Kingdom, India, Nepal and Pakistan) is a person who earns a living as the driver of a truck (usually a semi truck, box truck or dump truck).

Duties and functions

Truck drivers[2] provide an essential service to industrialized societies by transporting finished goods and raw materials over land, typically to and from manufacturing plants, retail and distribution centers. Truck drivers are also responsible for inspecting all their vehicles for mechanical items or issues relating to safe operation. Others, such as driver/sales workers, are also responsible for sales, completing additional services such as cleaning, preparation and entertaining (such as cooking and making hot drinks) and customer service.

Types

There are three major types of truck driver employment:

- Owner-operators (also known as O/Os, or "doublestuffs"[3]) are individuals who own the trucks they drive and can either lease their trucks by contract with a trucking company to haul freight for that company using their own trucks, or they haul loads for a number of companies and are self-employed independent contractors. There are also ones that lease a truck from a company and make payments on it to buy it in two to five years.

- Company drivers are employees of a particular trucking company and drive trucks provided by their employer.

- Independent Owner-Operators are those who own their own authority to haul goods and often drive their own truck, possibly owning a small fleet anywhere from 1-10 trucks, maybe as few as only 2 or 3 trucks.

Job categories

Both owner operators/owner driver and company drivers can be in these categories.

- Auto haulers work hauling cars on specially built trailers and require specific skills loading and operating this type of specialized trailer.

- Boat haulers work moving boats ranging in size from 10-foot-long (3.0 m) bass boats to full-size yachts up to 60 ft long (18 m) using a specialized low boy trailer that can be set up for each size of boat. Boats wider than 8 feet 6 inches (2.59 m) wide or 13 feet 6 inches (4.11 m) high have to have a permit to move and are an oversize load.

- Dry van drivers haul the majority of goods over highways in large trailers. Contents may be perishable or non perishable goods.

- Dry bulk pneumatic drivers haul bulk sand, salt, and cement, among other things. They have specialized trailers that allow them to use pressurized air to unload their product. - Commonly known as Flow Boys among truckers.

- Flat bed drivers haul an assortment of large bulky items. A few examples are tanks, steel pipes and lumber. Drivers require the ability to balance the load correctly.

- LTL drivers (Location-to-Location) or "less than truck load" are generally more localized delivery jobs where goods are delivered by the driver at multiple locations, sometimes involving the pulling of double or triple trailer combinations.

- Reefer drivers haul refrigerated, temperature sensitive or frozen goods.

- Local drivers work only within the limits of their local areas. These areas may include crossing state lines, but drivers usually return home daily.

- Household goods drivers, or bedbuggers, haul personal effects for families who are moving from one home to another.

-2003.jpg)

- Regional drivers may work over several states near their homes. They may be away from home for short periods.

- Interstate drivers (otherwise known as "over the road" or "long-haul" drivers) often cover distances of thousands of miles and are away from home for days, weeks or even months on end. For time critical loads, companies may opt to employ team drivers which can cover more miles than a single driver.

- Team drivers are two drivers who take turns driving the same truck in shifts (sometimes spouses), or several people in different states that split up the haul (line haul) to keep from being away from home for such long periods.

- Tanker drivers (tank truck drivers; in truck driver slang tanker yankers "tankies") haul liquids, such as gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, milk, & crude oil, and dry bulk materials, such as plastics, sugar, flour, & cement in tanks. Liquid tanker drivers need special driving skills due to the load balance changing from the liquid movement. This is especially true for food grade tankers, which do not contain any baffles and are a single compartment (due to sanitation requirements). Also fuel oil/petroleum drivers require special certifications.

- Vocational drivers drive a vocational truck such as a tow truck, dump truck, garbage truck, or cement mixer.

- Drayage drivers move cargo containers (aka "piggy backs") which are lifted on or off the chassis, at special intermodal stations.

- Bullrack haul livestock locally around their hometowns, or haul regionally all over the USA. The term bullrack comes from a double deck trailer used strictly to haul cattle.

Hours regulations

Australia

In Australia, drivers of trucks and truck and trailer combinations with gross vehicle mass greater than 12 tonnes (11.8 long tons; 13.2 short tons)[4] must rest for 15 minutes every 5.5 hours, 30 minutes every 8 hours and 60 minutes every 11 hours (includes driving and non-driving duties). In any 7 day period, a driver must spend 24 hours away from his/her vehicle. Truck drivers must complete a logbook documenting hours and kilometres spent driving.[5]

Canada

In Canada, driver hours of service regulations are enforced for any driver who operates a "truck, tractor, trailer or any combination of them that has a gross vehicle weight in excess of 4,500 kg (9,921 lb) or a bus that is designed and constructed to have a designated seating capacity of more than 24 persons, including the driver".[6] However, there are two sets of hours of service rules, one for above 60th parallel north, and one for below. Below latitude 60 degrees drivers are limited to 14 hours on duty in any 24-hour period. This 14 hours includes a maximum of 13 hours driving time. Rest periods are 8 consecutive hours in a 24-hour period, as well as an additional 2-hour period of rest that must be taken in blocks of no less than 30 minutes.

Additionally, there is the concept of "Cycles". Cycles in effect put a limit on the total amount of time a driver can be on duty in a given period before he must take time off. Cycle 1 is 70 hours in a 7-day period, and cycle 2 is 120 hours in a 14-day period. A driver who uses cycle 1 must take off 36 hours at the end of the cycle before being allowed to restart the cycle again. Cycle 2 is 72 hours off duty before being allowed to start again.

Receipts for fuel, tolls, etc., must be retained as a MTO officer can ask to see them in order to further verify the veracity of information contained in a driver's logbook during an inspection.

European Union

In the European Union, drivers' working hours are regulated by EU regulation (EC) No 561/2006[7] which entered into force on April 11, 2007. The non-stop driving time may not exceed 4.5 hours. After 4.5 hours of driving the driver must take a break period of at least 45 minutes. However, this can be split into 2 breaks, the first being at least 15 minutes, and the second being at least 30 minutes in length.

The daily driving time shall not exceed 9 hours. The daily driving time may be extended to at most 10 hours not more than twice during the week. The weekly driving time may not exceed 56 hours. In addition to this, a driver cannot exceed 90 hours driving in a fortnight. Within each period of 24 hours after the end of the previous daily rest period or weekly rest period a driver must take a new daily rest period. An 11-hour (or more) daily rest is called a regular daily rest period. Alternatively, a driver can split a regular daily rest period into two periods. The first period must be at least 3 hours of uninterrupted rest and can be taken at any time during the day. The second must be at least 9 hours of uninterrupted rest, giving a total minimum rest of 12 hours. A driver may reduce his daily rest period to no less than 9 continuous hours, but this can be done no more than three times between any two weekly rest periods; no compensation for the reduction is required. A daily rest that is less than 11 hours but at least 9 hours long is called a reduced daily rest period. When a daily rest is taken, this may be taken in a vehicle, as long as it has suitable sleeping facilities and is stationary.

‘Multi-manning’ The situation where, during each period of driving between any two consecutive daily rest periods, or between a daily rest period and a weekly rest period, there are at least two drivers in the vehicle to do the driving. For the first hour of multi-manning the presence of another driver or drivers is optional, but for the remainder of the period it is compulsory. This allows for a vehicle to depart from its operating centre and collect a second driver along the way, providing that this is done within 1 hour of the first driver starting work. Vehicles manned by two or more drivers are governed by the same rules that apply to single-manned vehicles, apart from the daily rest requirements. Where a vehicle is manned by two or more drivers, each driver must have a daily rest period of at least 9 consecutive hours within the 30-hour period that starts at the end of the last daily or weekly rest period. Organising drivers’ duties in such a fashion enables a crew's duties to be spread over 21 hours. The maximum driving time for a two-man crew taking advantage of this concession is 20 hours before a daily rest is required (although only if both drivers are entitled to drive 10 hours). Under multi-manning, the ‘second’ driver in a crew may not necessarily be the same driver from the duration of the first driver's shift but could in principle be any number of drivers as long as the conditions are met. Whether these second drivers could claim the multi-manning concession in these circumstances would depend on their other duties. On a multi-manning operation the first 45 minutes of a period of availability will be considered to be a break, so long as the co-driver does no work.

Journeys involving ferry or train transport Where a driver accompanies a vehicle that is being transported by ferry or train, the daily rest requirements are more flexible. A regular daily rest period may be interrupted no more than twice, but the total interruption must not exceed 1 hour in total. This allows for a vehicle to be driven on to a ferry and off again at the end of the crossing. Where the rest period is interrupted in this way, the total accumulated rest period must still be 11 hours. A bunk or couchette must be available during the rest period.

Weekly rest A regular weekly rest period is a period of at least 45 consecutive hours. An actual working week starts at the end of a weekly rest period, and finishes when another weekly rest period is commenced, which may mean that weekly rest is taken in the middle of a fixed (Monday–Sunday) week. This is perfectly acceptable – the working week is not required to be aligned with the ‘fixed’ week defined in the rules, provided all the relevant limits are complied with. Alternatively, a driver can take a reduced weekly rest period of a minimum of 24 consecutive hours. If a reduction is taken, it must be compensated for by an equivalent period of rest taken in one block before the end of the third week following the week in question. The compensating rest must be attached to a period of rest of at least 9 hours – in effect either a weekly or a daily rest period. For example, where a driver reduces a weekly rest period to 33 hours in week 1, he must compensate for this by attaching a 12-hour period of rest to another rest period of at least 9 hours before the end of week 4. This compensation cannot be taken in several smaller periods. A weekly rest period that falls in two weeks may be counted in either week but not in both. However, a rest period of at least 69 hours in total may be counted as two back-to-back weekly rests (e.g. a 45-hour weekly rest followed by 24 hours), provided that the driver does not exceed 144 hours’ work either before or after the rest period in question. Where reduced weekly rest periods are taken away from base, these may be taken in a vehicle, provided that it has suitable sleeping facilities and is stationary.

Unforeseen events Provided that road safety is not jeopardised, and to enable a driver to reach a suitable stopping place, a departure from the EU rules may be permitted to the extent necessary to ensure the safety of persons, the vehicle or its load. Drivers must note all the reasons for doing so on the back of their tachograph record sheets (if using an analogue tachograph) or on a printout or temporary sheet (if using a digital tachograph) at the latest on reaching the suitable stopping place (see relevant sections covering manual entries). Repeated and regular occurrences, however, might indicate to enforcement officers that employers were not in fact scheduling work to enable compliance with the applicable rules. [8]

New Zealand

Heavy vehicle work time requirements[9] in New Zealand are:

- A break of at least 30 minutes every 5.5 hours of work time

- Maximum cumulative work time of 13 hours (plus 2x 30-minute breaks) in one cumulative work day before a 10-hour break is required, giving a total of 24 hours.

- After 70 hours of accumulated work a driver must have a break of at least 24 hours

Emergency services drivers can exceed work hours when attending priority calls.

United States

In the United States, the hours of service (HOS) of commercial drivers are regulated by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA). Commercial motor vehicle (CMV) drivers are limited to 11 cumulative hours driving in a 14-hour period, following a rest period of no less than 10 consecutive hours. Drivers employed by carriers in "daily operation" may not work more than 70 hours within any period of 8 consecutive days.[10]

Drivers must maintain a daily 24-hour logbook record of duty status documenting all work and rest periods. The record of duty status must be kept current to the last change of duty status and records of the previous seven days retained by the driver in the truck and presented to law enforcement officials on demand.

Electronic on-board recorders (EOBR) can automatically record, among other things, the time the vehicle is in motion or stopped. An FMCSA ruling mandated use of EOBR's, also known as Electronic Logging Device (ELD), to begin on December 18, 2017. The new mandate is applicable to all carriers not under FMCSA exemptions.[11][12]

A shortage of truck drivers has been reported in the United States. Retention rates are low.[13]

Compensation

Truck drivers are paid according to many different methods. These include salary, hourly, and a number of methods which can be broadly defined as piece work. Piece work methods may include both a base rate and additional pay. Base rates either compensate drivers by the mile or by the load.

A company driver who makes a number of "less than truckload" (LTL) deliveries via box truck or conventional tractor-trailer may be paid an hourly wage, a certain amount per mile, per stop (aka "drop" or "dock bump") or per piece delivered, unloaded or tailgated (i.e., moved to the rear of the trailer).

The main advantage of being paid by the mile may be that a driver is rewarded according to measurable accomplishment. The main disadvantage is that what a driver may accomplish is not so directly related to the effort and, perhaps especially, the time required for completion.

Household good drivers deal with the most complexity and thus are typically the highest paid, potentially making multiples of a scheduled freight-hauler.[14]

Pay by the mile

Mileage calculations vary from carrier to carrier. Hub miles, or odometer miles ("hub" refers to hubometer, a mechanical odometer mounted to an axle), pay the driver for every mile. Calculations are generally limited to no more than 3–5% above the estimates of mileage by the carrier before red flags appear, depending on the generosity of the carrier or how it rates the mileage estimation capabilities of the software used. One version of hub miles includes only those per carrier designated route, i.e., a set number of miles. "Out of route" miles of any incentive are provided by the driver to the carrier for free.

Many of the largest long haul trucking companies in the United States pay their drivers according to short miles. Short miles are the absolute shortest distance between two or more zip codes, literally a straight line drawn across the map. These short miles rarely reflect the actual miles that must be driven in order to pick up and deliver freight, but they will be used to calculate what the driver will earn.

Short miles are on average about ten percent less than actual miles but in some cases the difference can be as large as 50 percent. An extreme (but not unheard of) example would be a load that picked up in Brownsville, Texas, and delivered in Miami, Florida. This journey would require the driver to travel over 1600 miles. The short routing however would believe the distance to be only 750, as though the truck could drive across the Gulf of Mexico. Another extreme example would be a load that picked up in Buffalo, New York, and delivered in Green Bay, Wisconsin, not giving any consideration that three of America's Great Lakes lie between that load's origin and destination.

Other obvious obstacles would be mountains and canyons. Truck prohibited routes sometimes create this same phenomenon, requiring a driver to drive several truck-legal routes and approaching a destination from behind (essentially driving a fish hook-shaped route), because the most direct route cannot accommodate heavy truck traffic.

Some trucking companies have tried to alleviate some of these discrepancies by paying their drivers according to "practical miles". This is where dispatch gives them a certain route to follow and will pay them for those. This is done in effort of compensating drivers for the actual work done. These routes will largely follow the Interstate Highway system but will sometimes require the driver to use state and U.S. highways and toll roads. Trucking companies practice this method in order to attract and retain veteran drivers. Household goods (HHG) miles, from the Household Goods Mileage Guide (aka "short miles") was the first attempt at standardizing motor carrier freight rates for movers of household goods, some say at the behest of the Department of Defense for moving soldiers around the country, long a major source of steady and reliable revenue. Rand McNally, in conjunction with the precursor of the National Moving & Storage Association[15] developed the first Guide published in 1936, at which point it contained only about 300 point-to-point mileages.[16]

Today, the 19th version of the Guide has grown to contain distances between more than 140,000 cities, zip codes, or highway junctions.[17]

Paid by the load

Getting paid by percentage is the preferred way of business among veteran drivers and owner-operators. Typical percentage among owner-operators pulling flatbed trailers is between 85-90 percent of line haul being paid to the driver. Additionally the driver may receive 100 percent of fuel surcharges and fees for extra pickups or drops or for tarping loads. It creates strong incentives for drivers for agreeing to pull especially difficult loads; i.e. pieces that are especially heavy or large, that require tarping, pieces that are being shipped or received along treacherous routes far from the interstates. It also discourages drivers and owner-operators from agreeing to move "cheap freight". Percentage of load is the simplest way of calculating what a driver and his/her truck will earn.

Paid by the hour

Companies such as Dupré Logistics, that traditionally paid by the mile have switched to hourly wages.[18] Regional and local drivers are usually paid by the hour.[19] In 2011 the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported the average heavy and over-the-road truck driver hourly wage to be $21.74 per hour.[20] The BLS reported in 2012 that the median hourly wage was $18.37 per hour.[21] In May 2013 the BLS reported a mean average hourly pay of from $12.21 (bottom 10%) to $28.66 per hour (top 10%).[22] In March 2014, Payscale.com published that the entry-level truck driver ranged from $11.82 to $20.22 an hour and the average hourly rate was reported as $15.53 an hour.[23] Certain special industry driving jobs such as oilfield services like vacuum, dry bulk, and winch truck drivers, can receive a $22.00 or higher hourly wage.[24]

Special licences

Australia

In Australia heavy vehicle licenses are issued by the states but are a national standard; there are 5 classes of license required by drivers of heavy vehicles:

- A Light Rigid (LR class) license covers a rigid vehicle with a gross vehicle mass (GVM) not more than 8 tons, with a towed trailer not weighing more than 9 tons GTM (Gross Trailer Mass). Also, buses with a GVM up to 8 tons which carry more than 12 adults including the driver.

- A Medium Rigid (MR class) license covers a rigid vehicle with 2 axles and a GVM of more than 8 tons, with a towed trailer not weighing more than 9 tons GTM.

- A Heavy Rigid (HR class) license covers a rigid vehicle with 3 or more axles with a towed trailer not weighing more than 9 tons GTM. Also articulated buses.

- A Heavy Combination (HC class) license covers semi-trailers, or rigid vehicles towing a trailer with a GTM of more than 9 tons.

- A Multi-Combination (MC class) license covers multi-combination vehicles like Road Trains and B-Double Vehicles.

A person must have a C class (car) licence for 1 year before they can apply for an LR or MR class licence and 2 years before they can apply for an HR, to upgrade to an HC class licence a person must have an MR or HR class licence for 1 year and to upgrade to an MC class licence a person must have an HR or HC class licence for 1 year.[25]

Canada

A driver's license in Canada, including commercial vehicle licenses, are issued and regulated provincially. Regarding CDL (commercial drivers licenses), there is no standardization between provinces and territories.[26]

European Union

In the EU, one or more of the categories of Large Goods Vehicle (LGV) licenses is required.

Medium Sized Vehicles:

C1 Lorries between 3500 kg and 7500 kg with a trailer up to 750 kg.

Medium Sized vehicles with trailers:

C1+E Lorries between 3500 kg and 7500 kg with a trailer over 750 kg - total weight not more than 12000 kg (if you passed your category B test prior to 1.1.1997 you will be restricted to a total weight not more than 8250 kg).

Large Vehicles:

C Vehicles over 3500 kg with a trailer up to 750 kg.

Large Vehicles with trailers:

C+E Vehicles over 3500 kg with a trailer over 750 kg.

In Australia, for example, a HC license covers buses as well as goods vehicles in the UK and most of the EU however a separate license is needed.

Minibuses:

D1 Vehicles with between 9 and 16 passenger seats with a trailer up to 750 kg.

Minibuses with trailers:

D1+E Combinations of vehicles where the towing vehicle is in subcategory D1 and its trailer has a MAM of over 750 kg, provided that the MAM of the combination thus formed does not exceed 12000 kg, and the MAM of the trailer does not exceed the unladen mass of the towing vehicle.

Buses:

D Any bus with more than 8 passenger seats with a trailer up to 750 kg.

Buses with trailers:

D+E Any bus with more than 8 passenger seats with a trailer over 750 kg.

United States

The United States employs a truck classification system, and truck drivers are required to have a commercial driver's license (CDL) to operate a CMV with a gross vehicle weight rating in excess of 26,000 pounds.

Acquiring a CDL requires a skills test (pre-trip inspection and driving test), and knowledge test (written) covering the unique handling qualities of driving a large, heavily loaded commercial vehicle, and the mechanical systems required to operate such a vehicle (air brakes, suspension, cargo securement, et al.), plus be declared fit by medical examination no less than every two years. For passenger bus drivers, a current passenger endorsement is also required.

A person must be at least 18 years of age to obtain a CDL. Drivers under age 21 are limited to operating within their state of licensing (intrastate operation). Many major trucking companies require driver applicants to be at least 23 years of age, with a year of experience, while others will hire and train new drivers as long as they have a clean driving history.

The U.S. Department of Transportation (US DOT) stipulates the various classes of CDLs and associated licensing and operational requirements and limitations.[27]

- Class A – Any combination of vehicles with a GVWR (gross vehicle weight rating) of 26,001 or more pounds provided the GVWR of the vehicle(s) being towed is in excess of 10,000 pounds.

- Class B – Any single vehicle with a GVWR of 26,001 or more pounds, or any such vehicle towing a vehicle, not in excess of 10,000 pounds GVWR.

- Class C – Any single vehicle, or the combination of vehicles, that does not meet the definition of Class A or Class B, but is either designed to transport 16 or more passengers, including the driver or is placarded for hazardous materials.

A CDL can also contain separate endorsements required to operate certain trailers or to haul certain cargo.[27] These endorsements are noted on the CDL and often appear in advertisements outlining the requirements for employment.

- T – Double/triple trailers (knowledge test only)

- P – Passenger (knowledge test; skills test may be required for some operations. Required for bus drivers.)

- N – Tank vehicle (knowledge test only)

- H – Hazardous materials (knowledge test only, also requires fingerprint and background check since the September 11 attacks)[28]

- X – Combination of tank vehicle and hazardous materials

Other endorsements are possible, e.g., M endorsement to transport metal coils weighing more than 5,000 pounds (2,300 kg), but are tested and issued by individual states and are not consistent throughout all states (as of this writing, the M endorsement is peculiar to the state of New York). The laws of the state from whence a driver's CDL is issued are considered the applicable laws governing that driver.

If a driver either fails the air brake component of the general knowledge test or performs the skills test in a vehicle not equipped with air brakes, the driver is issued an air brake restriction, restricting the driver from operating a CMV equipped with air brakes.

Specifically, the five-axle tractor-semitrailer combination that is most commonly associated with the word "truck" requires a Class A CDL to drive. Beyond that, the driver's employer (or shipping customers, in the case of an independent owner-operator) generally specifies what endorsements their operations require a driver to possess.

Truck regulations on size, weight, and route designations

U.S.

Truck drivers are responsible for checking the axle and gross weights of their vehicles, usually by being weighed at a truck stop scale. Truck weights are monitored for limits compliance by state authorities at a weigh station and by DOT officers with portable scales.

Commercial motor vehicles are subject to various state and federal laws regarding limitations on truck length (measured from bumper to bumper), width, and truck axle length (measured from axle to axle or fifth wheel to axle for trailers).

The relationship between axle weight and spacing, known as the Federal Bridge Gross Weight Formula, is designed to protect bridges.[29]

A standard 18-wheeler consists of three axle groups: a single front (steering) axle, the tandem (dual) drive axles, and the tandem trailer axles. Federal weight limits for NN traffic are:[30]

- 20,000 pounds for a single axle

- 34,000 pounds for a tandem axle

- 80,000 pounds for total weight

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) division of the US Department of Transportation (US DOT) regulates the length, width, and weight limits of CMVs used in interstate commerce.

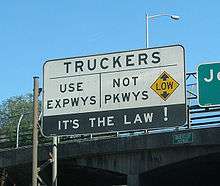

Interstate commercial truck traffic is generally limited to a network of interstate freeways and state highways known as the National Network (NN). The National Network consists of (1) the Interstate Highway System and (2) highways, formerly classified as Primary System routes, capable of safely handling larger commercial motor vehicles, as certified by states to FHWA.[31]

State weight and length limits (which may be lesser or greater than federal limits) affect the only operation of the NN. There is no federal height limit, and states may set their own limits which range from 13 feet 6 inches to 14 feet.[32] As a result, the height of most tractor/trailers range between 13' and 15'. States considered to be in the eastern half of the United States use 13'6" as the maximum height. The boundary states are Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Oklahoma (the only state west of the north/south line), Arkansas and Louisiana. States west of these have maximum heights of 14' with the exception of Colorado and Nebraska that have a maximum height of 14'6". Alaska has a maximum height of 15'.[33]

Uniquely, the State of Michigan has a gross vehicle weight limit of 164,000 pounds (74,000 kg), which is twice the U.S. federal limit. Although it is contended that this is one reason why Michigan has the worst roads in the country[34] (along with lack of funding—Michigan is dead last among the fifty states[upper-alpha 1]), a measure to change the law was just defeated in the Michigan Senate.[37][38][39][40][41]

Truck driver problems (U.S.)

Unpaid work time

In the United States, there is a lot of unpaid time, usually at a Shipper or Receiver where the truck is idle awaiting loading or unloading. Prior to the 2010 HOS changes it was common for 4–8 hours to elapse during this evolution. CSA addressed this and incorporated legal methods for drivers and trucking companies to charge for this excessive time. For the most part, loading/unloading times have fallen into a window of 2–4 hours although longer times are still endured.

Turnover and driver shortage

In 2006, the U.S. trucking industry as a whole employed 3.4 million drivers.[42] A major problem for the long-haul trucking industry is that a large percentage of these drivers are aging, and are expected to retire. Very few new hires are expected in the near future, resulting in a driver shortage. Currently, within the long-haul sector, there is an estimated shortage of 20,000 drivers. That shortage is expected to increase to 111,000 by 2014.[43] Trucking (especially the long-haul sector) is also facing an image crisis due to the long working hours, long periods of time away from home, the dangerous nature of the work, the relatively low pay (compared to hours worked), and a "driver last" mentality that is common throughout the industry.

To help combat the shortage, trucking companies have lobbied Congress to reduce driver age limits, which they say will reduce a recruiting shortfall. Under current law, drivers need to be 21 to haul freight across state lines, which the industry wants to lower to 18 years old.[44]

Employee turnover within the long-haul trucking industry is notorious for being extremely high. In the 4th quarter of 2005, turnover within the largest carriers in the industry reached a record 136%,[45] meaning a carrier that employed 100 drivers would lose an average of 136 drivers each year.

There is a shortage of willing trained long distance truck drivers.[46]

Part of the reason for the shortage is the economic fallout from deregulation of the trucking industry. Michael H. Belzer is an internationally recognized expert on the trucking industry, especially the institutional and economic impact of deregulation.[47] He is an associate professor, in the economics department at Wayne State University. He is the author of Sweatshops on Wheels: Winners and Losers in Trucking Deregulation (Oxford University Press, 2000).[48] His major opus was critically well received. Low pay, bad working conditions and unsafe conditions have been a direct result of deregulation. "[This book] argues that trucking embodies the dark side of the new economy."[49] "Conditions are so poor and the pay system so unfair that long-haul companies compete with the fast-food industry for workers. Most long-haul carriers experience 100% annual driver turnover.[50] As the Atlanta Journal-Constitution wrote: "The cabs of 18-wheelers have become the sweatshops of the new millennium, with some truckers toiling up to 95 hours per week for what amounts to barely more than the minimum wage. [This book] is eye-opening in its appraisal of what the trucking industry has become."[47]

Time off

Due to the nature of the job, most drivers stay out longer than 4 weeks at a time. A few for months on end and even longer. For the average large company driver in the United States 6 weeks is the average, with each week out garnering the driver one day off. This accrues to a set maximum usually 6 or 7 days. This is the average for OTR (Over The Road) Line Haul and Regional drivers. Vocational and Local drivers are usually home every night or every other night. Most tractors are equipped with sleeper berths that range from 36" to as large as 86" in length. While there are larger sleepers that get up to 144" in length, these are not seen in the mainline segment of trucking. Those are usually seen in the specialized and household moving segments, where the load is either permitted for overweight or oversize or is very light yet bulky. [51]

Safety

From 1992–1995, truck drivers had a higher total number of fatalities than any other occupation, accounting for 12% of all work-related deaths.[52] By 2009, truck drivers accounted for 16.8% of transportation-related deaths.[53] In 2016 alone, 475,000 crashes involving large trucks were reported to the police: 0.8% were fatal and 22% resulted in injury.[54] Among crash fatalities generally, 11.8% involved at least one large truck or bus.[55] In 2016, property damages resulting from truck and bus crashes cost several billion dollars.[55]

Truck drivers are five times more likely to die in a work-related accident than the average worker.[56] Highway accidents accounted for a majority of truck driver deaths, most of them caused by confused drivers in passenger vehicles who are unfamiliar with large trucks.

The unsafe actions of automobile drivers are a contributing factor in about 70 percent of the fatal crashes involving trucks. More public awareness of how to share the road safely with large trucks is needed.[57]

Still, progress has been made. While there has been a 29% increase in fatal crashes since 2009, this number is still lower than what it was in 2005.[54] The safety of truck drivers and their trucks is monitored and statistics compiled by the FMCSA or Federal Motor Carriers Safety Administration who provides online information on safety violations. If a truck is stopped by a law enforcement agent or at an inspection station, information on the truck complies and OOS violations are logged. A violation out of service is defined by federal code as an imminent hazard under 49 U.S.C. § 521(b)(5)(B), "any condition likely to result in serious injury or death". National statistics on accidents published in the FMCSA Analysis and Information online website provides the key driver OOS categories for the year 2009 nationally: 17.6% are log entry violations, 12.6% are speeding violations, 12.5% drivers record of duty not current, and 6.5% requiring driver to drive more than 14 hours on duty. This has led to some insurance companies wanting to monitor driver behavior and requiring electronic log and satellite monitoring.[58]

In 2009[59] there were 3380 fatalities involving large trucks, of which 2470 were attributed to combination unit trucks (defined as any number of trailers behind a tractor). In a November 2005 FMCSA report to Congress,[60] the data for 33 months of large truck crashes was analyzed. 87 percent of crashes were driver error. In cases where two vehicles, a car and a truck, were involved, 46 percent of the cases involved the truck's driver and 56 percent involved the car's driver. While the truck and car in two vehicle accidents share essentially half the burden of the accidents (not 70 percent as stated above), the top six driver factors are essentially also the same and in approximately equivalent percentages: Prescription drug use, over the counter drug use, unfamiliarity with the road, speeding, making illegal maneuvers, inadequate surveillance. This suggests that the truck driver makes the same errors as the car driver and vice versa. This is not true of the vehicle caused crashes (about 30 percent of crashes) where the top failure for trucks is caused by the brakes (29 percent of the time compared to 2% of the time for the car).

Truck drivers often spend their nights parked at a truck stop, rest area, or on the shoulder of a freeway ramp. Sometimes these are in secluded areas or dangerous neighborhoods, which account for a number of deaths due to drivers being targeted by thieves for their valuable cargo, money, and property, or for the truck and trailer themselves. Drivers of trucks towing flatbed trailers are responsible for securing and strapping down their cargo (which often involves climbing onto the cargo itself), and if the load requires tarping necessitates climbing on the load to spread out tarps. Tarps can weigh up to 200 lbs each and the cargo can require up to 3 tarps per load which account for a number of deaths and injuries from falling. Drivers spend long hours behind the wheel, which can cause strain on the back muscles. Some drivers are responsible for unloading their cargo, which can lead to many back strains and sprains due to overexertion and improper lifting techniques. If the cab of the truck is not appropriate for the driver's size, the driver can lose visibility and easy access to the controls and be at higher risk for accidents.[53]

Parking

A study published in 2002 by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) division of the U.S. Department of Transportation (US DOT) shows that "parking areas for trucks and buses along major roads and highways are more than adequate across the nation when both public (rest areas) and commercial parking facilities are factored in."[61]

A 2000 highway special investigation report by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) contains the following statistics:

- Parking spaces at private truck stops- 185,000 (estimate)

- Number of trucks parked at private truck stops at night- 167,453 (estimate)

- Private truck stops that are full on any given night nationwide- 53 percent

- Shortfall of truck parking spaces- 28,400 (estimate)

- Public rest areas with full or overflowing parking at night 80 percent[62]

One challenge of finding truck parking is made difficult perhaps not because there are insufficient parking spaces "nationwide", but where the majority of those spaces are not located, and most needed; near the most densely populated areas where demand for trucked goods is greatest.

As urban areas continue to sprawl, land for development of private truck stops nearby becomes prohibitively expensive and there seems to be an understandable reluctance on the part of the citizenry to live near a facility where a large number of trucks may be idling their engines all night, every night, or to experience the associated increase in truck traffic on local streets.

Exacerbating the problem are parking restrictions or prohibitions in commercial areas where plenty of space exists and the fact that shippers and receivers of freight tend to prefer to ship and receive truckloads in the early and late portions of the business day.

The end result is an increase in truck traffic during the morning and evening rush hours when traffic is most dense, commuters exhibit the least patience, and safety is compromised.

Adding to the challenge of finding parking are:

- A driver can only become familiar with locations of public and commercial parking spaces and their capacity and traffic by visiting them.

- The parking shortage, real or perceived, nearest the densest urban areas incites drivers to arrive early and many of those truck stops are full by 7 pm leaving even drivers who carefully plan their trips in detail few if any, options.

Idling restrictions

Idling restrictions further complicate the ability of drivers to obtain adequate rest, as this example from California may illustrate:

Commercial diesel-fueled vehicles with a GVWR greater than 10,000 pounds are subject to the following idling restrictions effective February 1, 2005. You may not:

- idle the vehicle's primary diesel engine for greater than five minutes at any location.[63]

- operate a diesel-fueled auxiliary power system which powers a heater, air conditioner, or any additional equipment for sleeper-berth equipped vehicles during sleeping or resting periods for greater than five minutes at any location within 100 feet of a restricted area.

Drivers are subject to both civil and criminal penalties for violations of this regulation."[64]

DAC Reporting

A truck driver's “DAC Report” refers to the employment history information submitted by former employers to HireRight & USIS Commercial Services Inc. (formerly called DAC Services, or “Drive-A-Check”). Among other things, a truck driver's DAC Report contains the driver's identification (Name, DOB, SSN), the name and address of the contributing trucking company, the driver's dates of employment with that company, the driver's reason for leaving that company, whether the driver is eligible for rehire, and comments about the driver's work record (e.g. good, satisfactory, too many late deliveries, etc.). It will also indicate whether the company stored drug and alcohol testing information with USIS. A separate section of the DAC report contains incident/accident information as well as CSA 2010 Pre-Employment Screening Program (PSP) Reports.[65]

False reports

The DAC report is as critical to the livelihood of a professional truck driver as the credit report is to a consumer. When a trucking company reports negative information about a truck driver, it can ruin the driver's career by preventing him or her from finding a truck driving job for several years or more. It is widely known that trucking companies often abuse this power by willfully and maliciously reporting false information on truckers’ DAC reports, either in retaliation for seeking better paying trucking jobs elsewhere or for any number of other fraudulent, anti-competitive reasons. As long as truck drivers can be threatened with a false DAC report for standing up to management or leaving their company for a better job elsewhere, working conditions at truck driver jobs will not improve.[66]

COVID-19 pandemic

Truck drivers in the United States are on the frontline delivering essential goods to Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic.[67][68] Many truck businesses may refuse to take assignments that travel to areas experiencing active outbreaks, such as New York City.[69] They also found great difficulty in obtaining gas and sustenance as many travel stops have closed. [70][71]

Compliance, Safety and Accountability

In 2010 the FMCSA enacted the Compliance, Safety, and Accountability program, formerly known as Comprehensive Safety Analysis 2010 or CSA 2010, a data-driven safety compliance and enforcement program. The program was implemented to improve commercial motor vehicle (CMV) safety and prevent crashes, injuries, and fatalities using the carrier Safety Measurement System (SMS) using the Behavior Analysis Safety Improvement Categories (BASICs). The categories are: 1)- Unsafe Driving, 2)- Hours of Service (HOS) Compliance, 3)- Driver Fitness, 4)- Controlled Substances and Alcohol, 5)- Vehicle Maintenance, 6)- Hazardous Materials (HM) Compliance, and 7)- Crash Indicator. The HM and crash indicators are not currently publicly available.[72]

There have been improvements, such as the combining of the original Inspection Selection System (ISS) and the Motor Carrier Safety Status Measurement System (SafeStat) to create ISS-2 in 2000 but many issues remained unsolved.[73] A 2012 FMCSA rule change addressed issues but still presented many problems including the Hours of Service rules for those drivers falling under the required "record of duty status" (RODS). The system in use until 2019 uses a relative scoring system that is based on comparing carriers to their peers[74]

Concerns

There have long been truck driver and trucking industry members concerns over the scoring, the bias, especially to smaller carriers according to a General Accountability Office report,[75] associated with the scoring when non-preventable accidents are included, the public posting of the scoring, and a lack of state mandatory procedures ensuring that a citation that was not prosecuted, or that ended favorably for the driver or carrier, was retracted from the national database because it is flawed, artificially raising the driver or carrier scores, and the insurance industry uses these scores to assess risks on insurance.[76] The FMCSA had released a report that the CSA scoring works.[77]

The hours of service rules has been changed several times since 2010 and is a concern to carriers and drivers. With the new electronic logging device (ELD) rules that became mandatory on December 18, 2017, for carriers subjected to the RODS rules, more issues have resulted. Drivers need to be aware that along with the ELD rule is a mandate to carry a paper log book and verify that the ELD manual and instruction sheet is in the truck. A driver must be able to email or fax the data if directed by a DOT officer. If an ELD malfunctions a driver must create a paper log to comply with the seven or eight day requirements, as well as recording the vehicle inspection.[78]

Congress has mandated the system to be overhauled and proposed FMCSA rules were scrapped as a result. New rules being proposed and testing includes a new Item Response Theory (IRT) model to replace the current relative rankings system began being tested in September 2018 with changes due in 2019.[79]

Truck driver problems (U.K.)

Driver shortage

In 2014 the Road Haulage Association and Freight Transport Association (FTA) have called for the government to help address the shortage of qualified truck drivers in the UK.[80] According to the FTA, there is now a shortage of 59,000 truck drivers.[81] The average age of a truck driver is now 57.[82]

During February 2016 an independent survey on the driver shortage was carried out by a UK freight exchange. The purpose of the survey was to get the drivers opinions about the HGV driver shortage. The aim was to establish whether the results of the driver's survey could help the industry and government understand the issues that the drivers are currently facing.[83]

The findings of the survey showed that, in the opinion of the drivers, the three main contributing factors to the driver shortage are 1) Poor wages, 2) Poor driver facilities and 3) The way drivers are treated. Over a third of all drivers who participated in the survey felt that they were not being treated well by the companies they drove for.[84]

Satellite tracking

Many companies today utilize some type of satellite vehicle tracking or trailer tracking to assist in fleet management. In this context "tracking" refers to a location tracking and "satellite" refers either to a GPS or GLONASS satellites system providing location information or communications satellites used for location data transmission. A special location tracking device also known as a tracker or an AVL unit is installed on a truck and automatically determines its position in real-time and sends it to a remote computer database for visualizing and analysis.

An "in cab" communication device AVL unit often allows a driver to communicate with their dispatcher, who is normally responsible for determining and informing the driver of their pick-up and drop-off locations. If the AVL unit is connected to a Mobile data terminal or a computer it also allows the driver to input the information from a bill of lading (BOL) into a simple dot matrix display screen (commonly called a "Qualcomm" for that company's ubiquitous OmniTRACS system).

The driver inputs the information, using a keyboard, into an automated system of pre-formatted messages known as macros. There are macros for each stage of the loading and unloading process, such as "loaded and leaving shipper" and "arrived at the final destination". This system also allows the company to track the driver's fuel usage, speed, gear optimization, engine idle time, location, the direction of travel, and the amount of time spent driving.

Werner Enterprises, a U.S. company based in Omaha, Nebraska, has utilized this system to implement a "paperless log" system. Instead of keeping track of working hours on a traditional pen and paper based logbook, the driver informs the company of his status using a macro.

Health issues

Working conditions

Most truck drivers are employed as over-the-road drivers, meaning they are hired to drive long distances from the place of pickup to the place of delivery. During the short times while they are in heavily polluted urban areas, being inside the cab of the truck contributes much to avoiding the inhalation of toxic emissions, and on the majority of the trip, while they are passing through vast rural areas where there is little air pollution, truck drivers in general enjoy less exposure to toxic emissions in the air than the inhabitants of large cities, where there is an increased exposure to emissions from engines, factories, etc., which may increase the risk of cancer[85] and can aggravate certain lung diseases, such as asthma[86] in the general public who inhabit these cities. However, the few drivers who are hired to drive only within urban areas do not have this advantage of spending more time away from toxic emissions that is enjoyed by over-the-road drivers. Other conditions affecting the health of truck drivers are for example vibration, noise, long periods of sitting, work stress and exhaustion. For drivers in developing countries there are additional risks because roads are in appalling conditions and accidents occur more frequently. Truck drivers are even a high-risk group for HIV-infection in those countries.[87]

In order to address the hazards relative to driver fatigue, many countries have laws limiting the amount of time truck drivers can work. Many underdeveloped countries either lack such laws or do not enforce them.

Drivers who work in mines have extra health hazards due to their working conditions, as the roads they travel are particularly treacherous.[88]

Truck Driver Fatigue

Truck driver fatigue is defined by the US Department of Transportation's Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) as being caused by "physical and/or mental exertion, resulting in impaired performance".[89] Factors that increase truck driver fatigue include lack of sleep (quantity and quality), long work hours, sedentary lifestyle, poor diet, and general stress. Research has shown that while some truck drivers may get a sufficient amount of sleep, many suffer from undiagnosed sleep disorders that impact the quality of their sleep.[90] One study found that within a sample of surveyed truck drivers, 68.1% reported waking up during the night, 64.2% reported waking up feeling unrefreshed, and 51.6% reported waking up too early and not being able to go back to sleep.[90] These sleep experiences have been linked to cognitive deficits, fatigue, and excessive daytime sleepiness.[90] It is important to note that sleep deprivation and poor sleep quality, although of critical concern, are a subset of the larger issue of truck driver fatigue.

A contributing factor to truck driver fatigue is the stress associated with managing compliance to FMCSA's hours of service (HOS) regulations. Truckers are allowed to drive a maximum of 11 hours during a continuous 14-hour period, and must be off duty for at least 10 hours.[91] In addition, they are limited to the number of hours they can drive during any consecutive 7-day or 8-day period, depending on their employer's operations.[91] There are also reset rules, break requirements, and sleeper berth and short-haul exceptions. Truck drivers are required to keep a HOS-compliant log. Failure to produce a driver's log upon request by an enforcement official or non-compliance with HOA regulations, results in a driving penalty or fine.[91] Better electronic methods for maintaining and managing drivers' logs are needed to help reduce truck driver stress.

The FMCSA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration conducted an extensive study from April 2001 to December 2003 investigating the causes of large truck crashes. Researchers reported that in thirteen percent of the crashes resulting in fatalities or injuries, truck driver fatigue was present.[92] Another FMCSA study published in 2011 reported that large truck crashes were increasingly associated with driving times greater than 7 hours, which is when fatigue begins to affect performance.[93] The FMCSA also reported that in 2016 truck driver fatigue was a larger contributing factor than alcohol and drugs in fatal truck crashes.[94]

Sleep disorders and deprivation

Truck drivers are also sensitive to sleep disorders because of the long hours required at the wheel and, in many cases, the lack of adequate rest.[95] Driver fatigue is a contributing factor in 12% of all crashes and 10% of all near crashes. Traffic fatalities are high and many of them are due to driver fatigue. Drivers with obstructive sleep apnea have a sevenfold increased risk of being involved in a motor vehicle crash.[96] It is estimated that 2.4-3.9 million licensed commercial drivers in the US have obstructive sleep apnea[96] out of the estimated 18 million total Americans.[97] The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration says that as many 28 percent of commercial driver's license holders have sleep apnea.[98]

- Total costs attributed to sleep apnea-related crashes:

- 2000: $15.9 billion and 1,400 lives

- Treatment:

- Cost: $3.18 billion with 70% effectiveness of CPAP treatment

- Savings: $11.1 billion in collision costs and 980 lives annually (National Safety Council)

Research sponsored by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration and American Trucking Associations found:

- Almost one-third (28%) of commercial truck drivers have some degree of sleep apnea

- 17.6% have mild sleep apnea

- 5.8% have moderate sleep apnea

- 4.7% have severe sleep apnea[97]

A CDC report (No. 2014–150) states: Most drowsy driving crashes or near misses occur during: 0400 and 0600, 0000 and 0200, and 1400–1600 hours and drivers are at the highest risk of a sleep-related accident.[99] Thirty-seven percent of fatal crashes happened between 6PM and 6AM.[54]

Obstructive sleep apnea has been associated with obesity. FMCSA rules states:[100]

- 391.41(b) A person is physically qualified to drive a commercial motor vehicle if that person (5) has no established medical history or clinical diagnosis of a respiratory dysfunction likely to interfere with his/her ability to control and drive a commercial motor vehicle safely.

The FMCSA question and answer site is confusing. Question 1 states that a motor carrier is responsible for ensuring drivers are medically qualified for operating CMVs in interstate commerce.[101] The FMCSA published a proposed guidance for sleep apnea testing in April 2012. Carriers began requiring drivers be tested for the disorder using neck circumference and Body Mass Index (BMI). For a male anything above 17" and for a female 15" was the minimum criteria with drivers above that having to be tested.[102] Health care professionals had to be registered with the FMCSA after May 21, 2012, to give certifications, and carriers started to require checking.[103] The agency backed away from required testing.[104][105]

Australia health requirements

A new law was passed in Australia requiring that all "over the road" drivers carry their medical information with them when they "are on the clock". This will help drivers comply with this new law and can also help deliver quick, accurate medical assistance if and when needed.

Obesity

According to a 2007 study in the Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 86% of the estimated 3.2 million truck drivers in the United States are overweight or obese.[106] A survey conducted in 2010 showed that 69% of American truck drivers met their criteria for obesity, twice the percentage of the adult working for population in the US.[107] Some key risk factors for obesity in truckers are poor eating habits, lack of access to healthy food, lack of exercise, sedentary lifestyle, long work hours, and lack of access to care.[108]

Eighty percent of truckers have unhealthful eating patterns as a result of poor food choices and food availability at truck stops is partially to blame.[109] The options at truck stops are generally high calorie and high fat foods available through restaurants, fast-food, diners and vending machines.[110] Fresh produce and whole grain items are few and far between. Though 85% of mini-mart items are categorized as extremely unhealthy, 80% of these meals are considered a truck driver's main meal of the day.[109][111] Also, most of the foods carried by drivers in their trucks, whether or not stored in a refrigerator, are purchased from truck stops.[109] Research suggests that drivers value quality and taste much more than nutrition when selecting food.[111] Another issue is the pattern of extensive and irregular snacking while on the road and consumption of one large meal at the end of day.[109][110][111] The daily meal is often high in calories and may be the highlight of the trucker's day.[109] Food intake varies during working hours compared to days off and truckers eat meals at the wrong circadian phase during the day.[108]

Lack of exercise is another contributing factor to the obesity epidemic in the truck driver population. Almost 90% of truck drivers exercise only sometimes or never and only 8% exercise regularly.[112] This is largely determined by long work hours and tight deadlines, the adoption of a sedentary lifestyle and a lack of a place to exercise.[106][113] Though some fitness resources are available for truckers, most are scarce. Available areas are truck stops, highway rest areas, trucking terminals, warehouses, and the truck cab.[106] However, there are many parking restrictions and safety concerns in trying to incorporate exercise into the daily routine.[109]

Studies have found the risk of obesity increases in high demand, low control jobs, and more so in jobs with long work hours;[114] the truck driving industry falls under these categories. Also, daytime sleepiness and night disturbances are associated with obesity,[114] and are, therefore, common among truck drivers. Long haul drivers have tight schedules, so they tend to drive longer and get less sleep.[106] The U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) does have Hours of Service (HOS) regulations. Under the old rule, drivers could work up to 82 hours in 7 days. These regulations were modified in 2011; but the new rule only permits drivers to work up to 70 hours in 7 days.[115] There is now an 11-hour-per-day limit with 10 hours off required after the weekly shift.[116] Fines for companies which allow work beyond 11 hours are up to $11,000 and for drivers up to $2,750. Though these fines exist, there is minimal enforcement of the law.[115]

Obesity prevalence is affected by access to care for truckers. Company drivers often have issues with insurance, such as necessary pre-approval if out of network. Most owner-operator drivers do not have any kind of medical insurance (that is, in the USA where medical treatment isn't free of charge like most countries). Moreover, truckers have difficulties making an appointment on the road and often do not know where to stop for assistance. Many self-diagnose or ignore their health issue altogether.[117] Some are able to be seen at doctor's offices or private clinics while a large percentage depend on emergency rooms and urgent care visits.[117] The Department of Transportation has Convenient Care Clinics across the U.S., but those are hard to find and are few and far between. Health care costs are substantially higher for overweight and obese individuals, so obesity in the truck driver population puts a greater financial demand on the industry.[118]

Other health problems

A study of 1,600 truck drivers from 2014 found that truckers in the US smoke at twice the rate of other working adults in the United States; 51% of truckers reported that they smoked in a 2010 survey. 61% of truckers in the same survey reported having two or more risk factors, which were defined as high blood pressure, obesity, smoking, high cholesterol, no physical activity, or sleep deprivation (6 or fewer hours of sleep per 24 hours).[119] In another study from 2015, more than 91,000 truck drivers were surveyed and similar types of morbidity were found.[120] Truck drivers also suffer from musculoskeletal disorders, cardiovascular disease, and stress at higher rates.[88]

Implementation of drug detection

U.S.

| I, Ronald Reagan, President of the United States of America, find that: Drug use is having serious adverse effects upon a significant proportion of the national work force and results in billions of dollars of lost productivity each year; The Federal government, as an employer, is concerned with the well-being of its employees, the successful accomplishment of agency missions, and the need to maintain employee productivity; The Federal government, as the largest employer in the Nation, can and should show the way towards achieving drug-free workplaces through a program designed to offer drug users a helping hand and, at the same time, demonstrating to drug users and potential drug users that drugs will not be tolerated in the Federal workplace; The profits from illegal drugs provide the single greatest source of income for organized crime, fuel violent street crime, and otherwise contribute to the breakdown of our society; [...] By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and laws of the United States of America [...] deeming such action in the best interests of national security, public health and safety, law enforcement and the efficiency of the Federal service, and in order to establish standards and procedures to ensure fairness in achieving a drug-free Federal workplace and to protect the privacy of Federal employees, it is hereby ordered [....]

Sec. 8. Effective Date. This Order is effective immediately. |

| Excerpt of Reagan's Executive Order 12564 September 15, 1986[121] |

In the 1980s the administration of President Ronald Reagan proposed to put an end to drug abuse in the trucking industry by means of the then-recently developed technique of urinalysis, with his signing of Executive Order 12564, requiring regular random drug testing of all truck drivers nationwide, as well as employees of other DOT-regulated industries specified in the order, though considerations had to be made concerning the effects of an excessively rapid implementation of the measure. Making sudden great changes in the infrastructures of huge economies and the industries crucial to them always entails risks, the greater the change, the larger the degree. Because of the U.S. economy's strong dependence on the movement of merchandise to and from large metropolitan population centers separated by such great distances, a shortage of truck drivers could have far-reaching effects on the economy.[122]

After the 1929 stock-market crash, for example, the chain reaction of reduction in sales due to consumers' prioritizing and reducing purchases of luxury items, with companies responding by reducing production and increasing unemployment, exacerbating the cycle of reduction or elimination of production, sales, and employment, had the ultimate result of plunging the nation's economy into the Great Depression.

Likewise, it had to be considered that a sudden halting or stunting of the movement of merchandise, as would occur with a large and sudden vacating of the cargo-transportation workforce, would have similar consequences. Even the 1974 nationwide speed-limit reduction to 55 mph, which merely slowed the movement of merchandise, was followed by the recession of the late 1970s.

In the years and decades following Executive Order 12564, efforts to begin random drug testing and pre-employment drug screening of truck drivers were not expedited, leaving the change to occur gradually, out of concern for the dangers of excessively rapid change in economic infrastructure. Since then, a large number of tractor-trailer operators have left the industry in search of other employment, and a new generation of drivers has come in. Subsequent to the measure it became extremely difficult for truck drivers to engage in drug abuse and remain undetected.[123]

On 12/10/2015, The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) asked the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) to draft a proposed plan to address the use of synthetic drugs among truckers.[124] The NTSB also issued a call to pro-trucking bodies to educate their members about the dangers associated with truckers’ use of synthetic drugs, and to come up with a way to prevent their use while behind the wheel.[124]

Truck driver slang

U.S.

Truck drivers once had a highly elaborate and colorful vocabulary of slang for use over their CB radios, but with the high turnover in the industry in recent decades, this has all but vanished. Most of the newer generation of drivers in the U.S. today speak to one another over their CB radios (or other similar communication devices) in more or less standard English (as understood in the various regions of the country), although a few of the slang words and phrases have remained, and many of these have passed into use in the colloquial language of the general public.

"Smokey" and "bear" are still used to refer to police officers, especially state patrolmen, and sometimes "diesel bear" for a DOT officer, though many new-school drivers merely say "police", "policeman" and "cop". "Hammer" refers to the accelerator pedal, and "hammer lane" the left lane or passing lane on a freeway, in which traffic generally travels faster. "Handle", meaning a nickname, was once exclusively truck-driver slang, but has now passed into common use by the public, especially for pseudonyms used on Internet forums.

Most of the "ten codes" have fallen nearly or completely into disuse, except "10/4," meaning "message received," "affirmative," "okay," "understood," and occasionally "10/20," referring to the driver's location, (e.g., "What's your 20?")

Often older truck drivers speaking over their CB radios are frustrated at new-school truck drivers' lack of understanding of the trucking slang of the '60s, '70s and '80s, and grudgingly resort to standard English when communicating with them. However today the slang is mostly gone, and some companies such as Swift Transportation consider the CB a safety hazard and prohibit the installation of a CB radio in their tractors.

- Partial list of some truck-driver slang;[125]

|

|

.jpg) A bobtail truck tractor

|

Australia

- All Dark - Weigh Station Closed

- Bandag band-aid - Retread tyre

- Candy car– Highway Patrol police car, usually with high-visibility police decals

- Car park - carrier of cars

- Chook Truck - Carter of live chickens

- Clean Skin - Non recap tyre

- Clear to Jolls - (M1 Motorway Hawksbury Hill North of the river) No police cars in the area from Top of the hill to Jolls Bridge

- Clear to the river - (M1 Motorway Hawksbury Hill North of the river) No police cars in the area from Jolls Bridge to Hawksbury River

- The Dipper - (M1 Motorway) Ku-Ring-Gai Chase Road Overpass Hill on the F3 Freeway

- Dollar - 100 kilometres per hour (60 mph)

- Evel Knievel– a police motorcycle

- Flash for cash– speed camera (not to be confused with a manned radar gun)

- Hair dryer -hand held radar gun

- Hot plate or Barbie – weigh station

- Mail Box - Australia Post Truck * Double - Rego & Speed checking police car

- Revenue Straight - Straight (M1 Motorway) Between Dog Trap Rd overpass & Peaks Ridge Turn off

- The scalies or coneheads– Transport Safety inspectors who man checking/weigh stations

- Sesame Street - Hume Highway (Sydney to Melbourne)

- Tanker Wanker - Dry Cement, Flyash, Sugar, Flower ETC or Liquid Tanker Drivers

- Turd herder - carrier of stock (animal freight)

- Tyregator - tyre stripped off the rim and usually left lying on the road

Visual signaling

Vehicle-light signaling

U.S.

One form of unspoken communication between drivers is to flash headlights on or off once or twice to indicate that a passing truck has cleared the passed vehicle and may safely change lanes in front of the signaling vehicle. The passing driver may then flash the trailer or marker lights to indicate thanks. This signal is also sometimes used by other motorists to signal truck drivers.

Continual flashing of headlights or high beams after emerging from around a corner beside a high wall or from any roadway out of sight to oncoming traffic will alert a truck driver in the oncoming lanes to an accident or other obstruction ahead and will warn him to reduce speed or to proceed with caution. Since truck-driver language has no signal for "Do not move in front of me," nor has any understood length of time for turning headlights or high beams on or off, flashing the high-beams to say "Do not move in front of me" may be misinterpreted to mean that the truck is clear to proceed with the lane change in front of the vehicle giving the signal.

Europe

As a rule, "thanks" is signaled to the vehicle behind by switching between the left- and right-turn signal several times, whereas turning on the hazard-warning lights (both turn signals) means "Slow down; danger ahead". As cars would normally use the hazard-warning lights for "thanks", in trucks distinction is necessary. The truck blocks the view of drivers behind it, hence a distinction must be made between "Thanks for letting me pass" and "Danger in front, I may brake hard!" Turning on the left-turn signal (in a right-hand traffic country) when a vehicle behind attempts to overtake means "Back off; lane not clear", and turning on the right-turn signal means "Go ahead; lane clear".

Truck drivers also use flashing headlights to warn drivers in the oncoming lane(s) of a police patrol down the road. Though not official, two consecutive flashes indicate a police patrol, whereas a rapid series of flashing indicates DMV or other law-enforcement agency that only controls truck drivers. During the day time, the latter is sometimes accompanied by the signaling driver making a circle with both hands (as if holding a tachograph ring).

Flashing headlights to the vehicle in front (intended for the other driver to see in their mirror) has two meanings. Long flashes are used to signal a truck driver that they are clear to return to the lane. A series of rapid flashes generally means "You're doing something stupid or dangerous" as in "Do not move in front, trailer not clear!" or "I'm overtaking, move aside".

Truckers also use their 4 ways flashing up a steep hill, mountain roads and on ramps on express ways to let others know that they are traveling at a slow speed and to be cautious approaching them.

Greeting

In Europe, the general rule for truckers in a right hand driving country is to raise the left hand and to simply open the hand with all fingers extended without waving it at all with the palm facing forward, known as 'the flat hand'. Or a shorter version is to simply extend the fingers while still keeping the palm in contact with the steering wheel. Raising the right hand is also used in the same way but very rare.

In popular culture

Truck drivers have been the subject of many films, such as They Drive by Night (1940), but they became an especially popular topic in popular culture in the mid-1970s, following the release of White Line Fever, and the hit song "Convoy" by C. W. McCall, both in 1975. The main character of "Convoy" was a truck driver known only by his CB handle (C.B. name), "Rubber Duck". Three years later, in 1978, a film was released with the same name. In 1977, another film Smokey and the Bandit, was released, which revolves around the escapades of a truck driver and his friend as they transport a load of bootleg beer across state lines. Smokey and the Bandit spawned two sequels. The 1978 film F.I.S.T. was a fictionalized account of the unionization of the trucking industry in the earlier 20th century, while the future of truck driving was speculated on in the 1996 film Space Truckers in which trucking has gone beyond planetary loads to interplanetary ones. One episode of Cowboy Bebop, "Heavy Metal Queen", also features spacefaring "truck" drivers.

Truck drivers have also been villainously portrayed in such films as Duel, Joy Ride, The Transporter, Breakdown, The Hitcher, Thelma & Louise, Superman II, Supergirl, and Man of Steel.

B. J. and the Bear was a television series depicting the exploits of a truck driver and his chimpanzee companion. Another was Movin' On, starring Claude Akins and Frank Converse. On 17 June 2007, the History Channel began to air Ice Road Truckers, a documentary-style reality television series following truck drivers as they drive across the ice roads in the Northwest Territories in Canada, as they transport equipment to the oil and natural gas mines in that area.

Notes

References

- "truckie". www.thefreedictionary.com. Farlex inc. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- "Truck Driver Job Description". Betterteam. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- "Trucker Slang and CB Radio Lingo Dictionary - Talk Like a Trucker". TheTruckersReport.com. 1999-02-22. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- "National Heavy Vehicle Regulator Fatigue Management". Archived from the original on 2015-03-23. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- "Heavy vehicle log book requirements". Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- "Commercial Vehicle Drivers Hours of Service Regulations (SOR/2005-313)". 2009-11-28. Retrieved 2011-07-02.

- "EUR-Lex - 32006R0561 - EN". Eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 2010-10-07.

- "Rules on Drivers' Hours and Tachographs Goods vehicles in GB and Europe" (PDF). February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Heavy Vehicle Work Time Requirements". 2014-07-27. Retrieved 2014-11-24.

- "Hours of service of drivers, Part 395: Maximum driving time for property-carrying vehicles; Part 395.3". Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. Archived from the original on 2008-02-07. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- "ELD Checklist for Drivers". FMCSA. 2015-09-03. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- "E-log mandate set to take effect Dec. 2017, rule set for DOT publication". Overdrive. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- Badkar, Mamta (August 5, 2014). "There's A Huge Shortage Of Truck Drivers In America — Here's Why The Problem Is Only Getting Worse". Business Insider. Retrieved August 5, 2014.

- Murphy, Finn (June 2017). The Long Haul: A Trucker's Tales of Life on the Road. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393608717. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- National Moving & Storage Association

- Deborah Whistler (2002-02-10). "What's In A Mile?". Heavy Duty Trucking. Archived from the original on 2002-06-05. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- American Moving and Storage Association. "New Official Household Goods Transportation Mileage Guide 19 is Now Available!" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- hourly wages- Retrieved 2014-10-22

- jobmonkey.com-Retrieved 2014-10-22

- alltrucking.com- Retrieved 2014-10-22

- 2012 BLS report- Retrieved 2014-10-22

- BLS.gov- Retrieved 2014-10-22

- payscale.com- Retrieved 2014-10-22

- Pilot Logistics- Retrieved 2014-10-22

- "Licence" (PDF). Roads and Maritime Services. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- Canadian Driver's Licence Reference Guide. Commercial Vehicle Safety Alliance, April 1st, 2013. Online. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-17. Retrieved 2016-08-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Commercial Drivers License Program". fmcsa.dot.gov. U.S. Department of Transportation – Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- "HAZMAT Endorsement Threat Assessment Program". Transportation Security Administration. Archived from the original on 2008-02-23. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- "Bridge Formula Weights". US DOT/Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- "658.17". Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration. Archived from the original on 2008-01-04. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- "Commercial Vehicle Size and Weight Program". US DOT/Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved 2009-03-11.

- "Federal Size Regulations for Commercial Motor Vehicles" (PDF). ops.fhwa.dot.gov/. Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved 2008-02-03.

- "Trucking Legal Height Limits Map". Heavy Haul Trucking. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- Egan, Paul (March 13, 2018). "Does your body ache from hitting potholes? 5 reasons Michigan has lousy roads". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- Anderson, Bill (August 17, 2018). "Michigan's Road Spending: How do we stack up?". Southeast Michigan Council of Governments. Retrieved April 16, 2019.