Tropical Storm Emily (2011)

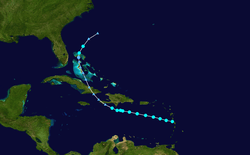

Tropical Storm Emily was a weak Atlantic tropical cyclone that brought torrential rains to much of the northern Caribbean in 2011. The fifth named storm of the annual hurricane season, Emily developed from a strong but poorly organized tropical wave that traversed the open Atlantic over the last week July. On August 1, it approached the Lesser Antilles and became more consolidated, producing inclement weather over many of the northern islands. Two days later, the disturbance’s wind flow became more cyclonic with a defined center of circulation, which marked the formation of Tropical Storm Emily. The storm remained fairly irregular in structure, though generating strong thunderstorms and gusty winds along its path over the Caribbean Sea. On August 4, Emily was declassified as a tropical cyclone after the mountainous areas of Hispaniola further disrupted its diffuse circulation. Upon exiting the northeastern Caribbean on August 6, its remnants briefly regenerated into a tropical storm before dissipating completely the next day.

| Tropical Storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Tropical Storm Emily at peak intensity in the Caribbean Sea on August 3 | |

| Formed | August 2, 2011 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | August 11, 2011[1] |

| (Remnant low after August 7) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 50 mph (85 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 1003 mbar (hPa); 29.62 inHg |

| Fatalities | 4 direct, 1 indirect |

| Damage | $5 million (2011 USD) |

| Areas affected | Antilles, Florida, Bahamas |

| Part of the 2011 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Despite the erratic structure of its wind flow, Emily brought severe weather to many Caribbean nations. Gusty winds felled trees and heavy rains caused widespread flooding throughout the Lesser Antilles. The most significant damage was confined to Martinique, where one death occurred. In Puerto Rico, flash floods affected residences and roads, leaving behind US$5 million in infrastructural damage. Even after Emily’s dissipation, its remnants continued to produce prolonged rainfall over much of Hispaniola. Floods and mudslides in the Dominican Republic displaced over 7,000 residents and caused three people to drown in the capital of Santo Domingo. In neighboring Haiti, hundreds of houses were inundated in the department of Artibonite, forcing their inhabitants to evacuate. Minor wind damage occurred throughout the country's southern peninsula, and one person died in that region.

Meteorological history

The cyclogenesis of Tropical Storm Emily was complicated, extending over several days from late July into early August. An easterly tropical wave—an equatorward trough of low pressure—exited the west African coast in the fourth week of July, at which point it became largely embedded within the monsoon trough.[2] Located to the south of a ride of high pressure, the wave moved west-northwestward across the open Atlantic; it retained a broad circulation with little to no precipitation for a day or two.[1][3] Over time, clusters of convection increased around the broad system, and it developed two distinct centers of circulation on July 30.[1][4][5] During the morning of July 31, the large low markedly gained in organization, and the National Hurricane Center (NHC) noted it was close to becoming a tropical depression.[6] Later that day, however, the main circulation became increasingly elongated; its westernmost component soon detached to form a separate tropical wave.[7] This new disturbance featured widely scattered convection and rainbands, which briefly affected the Lesser Antilles.[8] The next day, a new area of deep convection with a dominant center formed as the circulation became better defined. It passed through the Leeward Islands with some improvement in its structure, and the surface winds rose to near tropical storm force.[1][9] A reconnaissance flight into the system revealed the circulation center had become well defined near the deep convection. The system was upgraded to tropical storm status and given the name Emily at 0000 UTC on August 2, when it was located to the south of Dominica. During the initial stages of its existence, the storm accelerated toward the west-northwest in response to the strong high pressure to its north.[1][10]

With a relatively dry environment along its projected path, Emily was expected to strengthen only gradually until its predicted passage through the Greater Antilles.[11] For several hours into August 2, the cyclone fluctuated little in intensity and organization as it developed banding features.[12] Emily's appearance later improved on satellite images, and it developed a ragged central dense overcast; the NHC estimated that the storm had reached its peak sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) by 0000 UTC on August 3.[1] Nevertheless, reconnaissance revealed that its circulation remained poorly organized, and at the time, several forecast models even supported dissipation prior to landfall in Hispaniola.[13] An increase in upper wind shear removed the deepest convection from the circulation center, and it would remain so for the rest of the storm's duration.[14][15] On August 4, the cloud pattern and convective banding became better organized near the center as the upper outflow over the cyclone expanded.[16] Emily proceeded to track just south of the Dominican Republic,[17] where its weak circulation became increasingly disrupted due to the adjacent high terrain and increasing vertical wind shear. The cyclone accelerated over Hispaniola and degenerated into an open trough around 2100 UTC that day.[1][18]

The remnant trough proceeded northwestward into the Bahamas, where the NHC assessed a high chance of redevelopment based on relenting upper wind shear.[19] Over the next couple of days, it moved over the Bahamas and proceeded east of southern Florida. Late on August 6, the trough developed a new center of circulation and regenerated into a weak tropical depression by 1800 UTC near Grand Bahama. Emily briefly reattained tropical storm strength six hours later, although it once again dissipated to a remnant low the next day owing to increasing wind shear.[20] The low took on an accelerated east-northeastward motion, bypassing Bermuda before heading eastward over the open Atlantic. It briefly retained a broad area of gale-force winds with deep convection, which prompted the NHC to remonitor the system.[1][21] The combination of strong wind shear and its rapid forward speed inhibited significant development, and the remnant dissipated around 1200 UTC on August 11, about 980 mi (1,565 km) west of the Azores.[1]

Preparations

Because of the high potential for tropical cyclone development, Météo-France declared yellow cyclone alerts for Guadeloupe and Martinique, warning of imminent squally weather.[22][23] Due to the presence of Emily, a state of emergency was declared for all of Puerto Rico.[24] Officials ordered the preparation of over 400 storm shelters and ensured adequate water supply.[25] The morning before the storm, government workers were dismissed, and national courtrooms remained closed.[25] The United States Coast Guard issued a statement urging residents of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to avoid recreational boating and swimming until Emily had passed.[26] JetBlue Airways waived fees for flights into the Dominican Republic because of the inclement weather conditions.[27] Four cruise ships, Oasis of the Seas, Freedom of the Seas, Carnival Dream and Carnival Liberty altered their courses through the Caribbean to avoid the storm.[28]

In Haiti, about 630,000 people were still living in tents across areas devastated by the January 2010 earthquake prior to Emily's arrival. Due to the lack of sturdy structure to ride out a storm, fears arose over how they would fare with a tropical cyclone passing through the country. Emergency officials in the country set aside 22 large buses to evacuate thousands of people at the risk of flooding. Additionally, residents were urged to conserve food and safeguard their belongings. The United Nations placed 11,500 troops in the country on standby to assist in recovery efforts should they be necessitated. The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies also put emergency teams on standby to deliver food support in addition to the 125,000 people already assisted.[24] In advance of the storm, authorities closed all airports and landing sites in country.[29]

Impact

Lesser Antilles

Intense rainbands produced gusty winds and heavy precipitation totaling to 5.90 in (150 mm) in Martinique,[30] causing street flooding and inundating homes. Roughly 5,000 residences lost power at the height of the storm,[31] though the outages were brief and confined to the southeast of the island. A large landslide occurred in the capital of Fort-de-France due to excessive soil saturation, prompting some 40 families to evacuate the area.[32] Across the city, deep flood waters affected 29 houses;[33] a man was electrocuted and killed by an exposed wire in his flooded home.[34]

In Guadeloupe, damage from the storm was limited; potent gusts uprooted numerous trees and blew debris onto streets throughout Basse-Terre. One road was blocked off to traffic during its passage as a precautionary measure, but was reopened soon thereafter.[35] Gale-force winds downed some electricity lines in Saint Kitts and Nevis, causing two island-wide outages.[36] The storm enhanced moisture to produce intermittent torrents over the Virgin Islands, with localized totals of no more than 1 inch (25 mm). Winds in the area were also limited; the highest gust was experienced on Buck Island, measuring 52 mph (83 km/h).[37]

Puerto Rico

While moving little near Puerto Rico, Emily brought prolonged tropical storm conditions to many parts of the island. The heaviest rainfall occurred in southern regions; Caguas recorded a total of 8.22 in (209 mm) of rain during the storm.[1] High winds damaged an electrical grid, cutting off power to about 18,500 customers; roughly 6,000 people were left without drinking water during the storm.[38] Dozens of residents evacuated to shelters, in particular those living near risk zones.[39] Torrential rains of up to 10 inches (250 mm)[40] overflowed three rivers, which resulted in the flooding and subsequent closure of the PR-31 highway and PRI-3 intersection.[38] Throughout the island, multiple other roads were made impassable by landslides and fallen objects;[41] infrastructural damage surmounted $5 million, according to preliminary estimates.[42] The two-day suspension of about 280,000 employees—about 30 percent of the territory's workforce—affected the local economy significantly, with capital losses estimated at $55 million.[43]

In San Lorenzo, 25 families became isolated when a bridge threatened to collapse.[44] Flooded homes and cluttered streets were reported in Ceiba, with one residential gate collapsing in the municipality.[45] The agricultural sector also sustained losses from the storm; in Yabucoa, heavy rains washed out 1,200 acres (490 ha) of banana seedlings.[46]

Hispaniola

| Precipitation | Storm | Location | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | mm | in | |||

| 1 | 1001.5 | 39.43 | Flora 1963 | Polo Barahona | [47] |

| 2 | 905.0 | 35.63 | Noel 2007 | Angelina | [48] |

| 3 | 598.0 | 23.54 | Cleo 1964 | Polo | [47] |

| 4 | 528.0 | 20.79 | Emily 2011 | Neyba | [49] |

| 5 | 505.2 | 19.89 | Jeanne 2004 | Isla Saona | [50] |

| 6 | 479.8 | 18.89 | Inez 1966 | Polo | [51] |

| 7 | 445.5 | 17.54 | Hurricane Four 1944 | Hondo Valle | [52] |

| 8 | 391.4 | 15.41 | Hurricane Five 1935 | Barahona | [53] |

| 9 | 359.9 | 14.17 | Hanna 2008 | Oveido | [54] |

| 10 | 350.0 | 13.78 | T.S. One 1948 | Bayaguana | [55] |

Albeit disorganized, Emily and its remnants dropped extensive precipitation across the Dominican Republic, with maximum totals of up to 21 inches (528 mm) recorded in Neiba. Among other consequences, severe flooding and isolated mudslides left 56 communities isolated from surrounding areas.[56] The storm displaced up to 7,534 people throughout the country, of which 1,549 sought refuge in storm shelters.[57] Consecutive hours of rainfall resulted in the overflow of some rivers, although no significant damage was reported to adjacent areas.[58] Offshore, squalls generated rough waves that briefly affected boating operations and oceanside homes.[56] To the east of Santo Domingo, two men drowned after getting caught in a swollen river. A third drowning fatality occurred elsewhere in the capital due to flooding.[59]

Owing to the timing of its dissipation, Emily spared neighboring Haiti from the devastation initially anticipated. At least 235 people in Jacmel and Tabarre, as well as 65 prisoners from Gonaïves and Miragoâne, required evacuation at the height of the storm.[40] In Artibonite, civil protection teams evacuated roughly 300 residents.[40] Rainfall triggered floods that damaged over 300 homes throughout the country, while several cholera treatment centers were destroyed.[60] At the risk of new outbreaks, special sterilizers were distributed to sanitize possibly contaminated waters.[61] A body was recovered from a ravine near Les Cayes, but the exact cause of death was disputed; another person in the area sustained injuries after being hit by a fallen tree.[62] High winds caused some property damage in Léogâne and Jacmel.[60]

Elsewhere

The successor trough to Emily produced torrential rains over eastern Cuba, causing some rivers to overflow. Damaging flood waters spread across roads in Santiago de Cuba, where 37 homes were affected by mud. While regenerating into a tropical depression, Emily dropped prolonged rainfall in the Bahamas; a severe thunderstorm warning was accordingly issued for Grand Bahama and adjacent waters.[63] Precipitation totals of up to 7.9 in (200 mm) were recorded during the time.[64]

See also

- Other tropical cyclones named Emily

References

- Kimberlain, Todd B; Cangialosi, John P. (2012-01-13). Tropicical Cyclone Report Tropical Storm Emily (AL052011): 2–7 August 2011 (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2012-01-13.

- Tichacek, Mike (2011-07-26). "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- Tichacek, Mike (2011-07-27). "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- Tichacek, Mike (2011-07-28). "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- Formosa, Mike (2011-07-29). "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- Berg, Robbie (2011-07-31). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- Lewitsky, Jeffrey (2011-08-01). "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-09-11.

- Franklin, James; Brennan, Michael (2011-07-31). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- Stewart, Stacy (2011-08-01). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- Brennan, Michael (2011-08-01). "Tropical Storm Emily Discussion Number One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-01.

- Brennan, Michael (2011-08-02). "Tropical Storm Emily Discussion Number Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- Brennan, Michael (2011-08-02). "Tropical Storm Emily Discussion Number Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- Avila, Lixion (2011-08-02). "Tropical Storm Emily Discussion Number Four". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- Brennan, Michael (2011-08-02). "Tropical Storm Emily Discussion Number Five". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- Lixion, Avila (2011-08-03). "Tropical Storm Emily Discussion Number Eight". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-04.

- Lixion, Avila (2011-08-04). "Tropical Storm Emily Discussion Number Twelve". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-04.

- Lixion, Avila (2011-08-04). "Tropical Storm Emily Advisory Number Twelve". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-04.

- Lixion, Avila (2011-08-04). "Tropical Storm Emily Advisory Number Thirteen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-04.

- Stewart, Stacy (2011-08-05). "Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Brennan, Michael; Stewart, Stacy (2011-08-07). "Tropical Storm Emily Advisory Number Fourteen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- Pasch, Richard (2011-08-09). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2011-08-09.

- Saint-Joseph, Leïla (2011-08-01). "Météo: la Martinique en alerte jaune cyclone". kelDOM (in French). COMantilles. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- Staff writer (2011-07-31). "METEO: Alerte jaune cyclonique". France-Antilles (in French). France Antilles Martinique. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- Daniel Trenton (2011-08-03). "Haiti is next for Tropical Storm Emily". The Brownsville Herald. Freedom Communications. Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 3, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- Staff reporter (2011-08-01). "No hay trabajo en el Gobierno de Puerto Rico mañana". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). Grupo Ferré-Rangel. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- "Coast Guard urges mariners to exercise caution, prepare for tropical storm conditions in Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands". United States Coast Guard. August 2, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- "Operations Update". JetBlue Airways. 2011-08-02. Archived from the original on August 3, 2011. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- Sloan, Gene (2011-08-02). "Tropical Storm Emily scatters cruise ships in the Caribbean". USA Today. Gannett Company. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- Logistics Cluster (2011-08-31). "Situation Report Haiti Operation August 2011". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- "Weather in LAMENTIN AERO August 2011, Martinique". Geodata.us. 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- "Tempête Emily: un mort à la Martinique" (in French). France Télévisions. AFP; France 2. 2011-08-03. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- "Martinique/tempête: un mort électrocuté". Le Figaro (in French). Dassault Group. Agence France-Presse. 2011-08-02. Retrieved 2011-08-03.

- "Fort-de-France durement touché par la tempête Emily". Le Point (in French). Artémis. Agence France-Presse. 2011-08-03. Retrieved 2011-08-04.

- Chomereau-Lamotte, Dominique (2011-08-02). "Tempête Emily: un mort en Martinique". L'Express (in French). Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- Staff writer (2011-08-02). "Tempête Emily : premiers bilans en Guadeloupe". France-Antilles (in French). France Antilles Martinique. Retrieved 2011-08-04.

- Staff writer (2011-08-02). "Tropical Storm Emily brings high winds, rain to the region". The St. Kitts-Nevis Observer. St. Kitts-Nevis Publishing Association. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- Blackburn, Joy (2011-08-03). "Emily passes to south, has little impact on V.I." The Virgin Islands Daily News. Times-Shamrock Communications. Archived from the original on 2012-07-18. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Alvarado-León, Gerardo E. (2011-08-03). "Emily fue un ensayo". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). Grupo Ferré-Rangel. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Menchaca, Jerohim O. (2011-08-04). "Casi 30 refugiados tras el paso de Emily por la Isla". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). Grupo Ferré-Rangel. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Morgan, Curtis; Robles, Frances; Baron, Amelie (2011-08-05). "Flooding from Emily kills 4". The Miami Herald. The McClatchy Company. Archived from the original on 2012-01-14. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Staff reporter (2011-08-03). "Emily: Sigue las incidencias minuto a minuto". El Nuevo Día (in Spanish). Grupo Ferré-Rangel. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Alcaide, Maria D. (2011-08-05). "Pérdidas de $5 millones en carreteras". Primera Hora (in Spanish). Grupo Ferré-Rangel. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- EFE (2011-08-04). "El cese de operaciones del Gobierno por "Emily" acarreó pérdidas millonarias". La Prensa (in Spanish). La Prensa Foundation. Archived from the original on 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Cancel, Alex F. (2011-08-04). "Residentes preocupados por condición de puente en San Lorenzo". Primera Hora (in Spanish). Grupo Ferré-Rangel. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Staff writer (2011-08-03). "Alcalde de Ceiba informa de daños por culpa de Emily". Primera Hora (in Spanish). Grupo Ferré-Rangel. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Rosa, Bárbara J. F.; Cancel, Alex F.; Saavedra, Maelo V.; Doll, Sara J. (2011-08-05). "Evalúan las zonas afectadas por Emily". Primera Hora (in Spanish). Grupo Ferré-Rangel. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Roth, David M. (October 18, 2017). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- Brown, Daniel P (December 17, 2007). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Noel 2007 (PDF) (Technical report). United States National Hurricane Center. p. 4. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- (in Spanish) "Lluvias dejan 3 muertos y 7.000 evacuados". Hoy. Periódico Hoy. Associated Press. 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- (in Spanish) Hugo del Jesus Segura Soto (2005-07-18). "Inundaciones rápidas en la República Dominicana" (PDF). Centro de Estudios Hidrográficos. p. 57.

- ONAMET. Boletin Climatologico Mensual: Septiembre. Retrieved on 2007-03-09.

- ONAMET. Boletin Climatologico Mensual: Agosto. Retrieved on 2007-03-09.

- ONAMET. Boletin Climatologico Mensual: Octubre. Retrieved on 2007-03-09.

- Brown, Daniel P; Kimberlain, Todd B; National Hurricane Center (2009-03-27). Hurricane Hanna (PDF) (Tropical Cyclone Report). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved 2012-06-01.

- ONAMET. Boletin Climatologico Mensual: Mayo. Retrieved on 2007-03-09.

- "Lluvias dejan 3 muertos y 7.000 evacuados". Hoy (in Spanish). Periódico Hoy. Associated Press. 2011-08-05. Archived from the original on 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Paniagua, Soila; Rosario, Ivelisse (2011-08-04). "Emily deja 7,534 desplazados y a 47 comunidades aisladas". Hoy (in Spanish). Periódico Hoy. Archived from the original on 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Bonilla, Teofilo (2011-08-05). "Remanentes tormenta Emily aún se sienten". El Nacional (in Spanish). Ahora! Publications. Archived from the original on 2012-03-25. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- "Emily deja tres muertos en Dominicana". El Universal (in Spanish). Compañía Periodística Nacional. Associated Press. 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- Innocent, Clerna (2011-08-05). "Haïti. Dégâts limités après le passage d'Emily". Paris Match (in French). Lagardère Group. Archived from the original on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- WZZM Channel 13 (2011-08-05). "Local company sanitizing water in Haiti". ABC. Gannett Company. Archived from the original on 2013-02-09. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- "Haïti: la tempête Emily a fait un mort et de nombreuses familles sinistrées". La Presse (in French). Group Gesca. Agence France-Presse. 2011-08-05. Retrieved 2011-08-06.

- Nancoo-Russel, K. (2011-08-08). "Emily drenches GB with persistent rains". The Nassau Guardian. Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- Gutro, Rob (2011-08-10). "Hurricane Season 2011: Tropical Storm Emily (Caribbean Sea)". NASA. Retrieved 2011-09-07.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tropical Storm Emily (2011). |