Trombone

The trombone is a musical instrument in the brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's vibrating lips (embouchure) cause the air column inside the instrument to vibrate. Unlike most other brass instruments, which have valves that, when pressed, alter the pitch of the instrument, trombones instead have a telescoping slide mechanism that varies the length of the instrument to change the pitch. However, many modern trombone models also use a valve attachment to lower the pitch of the instrument. Variants such as the valve trombone and superbone have three valves similar to those on the trumpet.

A tenor trombone | |

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 423.22 (Sliding aerophone sounded by lip movement) |

| Developed | The trombone originates in the mid 15th century. Until the early 18th century it was called a sackbut in English. In Italian it was always called trombone, and in German, posaune. |

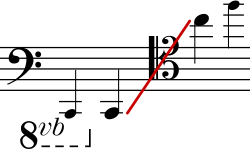

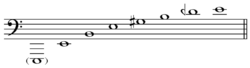

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| More articles or information | |

|

List of classical trombonists List of jazz trombonists Types of trombone | |

The word "trombone" derives from Italian tromba (trumpet) and -one (a suffix meaning "large"), so the name means "large trumpet". The trombone has a predominantly cylindrical bore like its valved counterpart, the baritone, in contrast to its conical valved counterparts: the cornet, the euphonium, and the French horn. The most frequently encountered trombones are the tenor trombone and bass trombone. The most common variant, the tenor, is a non-transposing instrument pitched in B♭, an octave below the B♭ trumpet and an octave above the pedal B♭ tuba. The once common E♭ alto trombone became less widely used as improvements in technique extended the upper range of the tenor, but it is now resurging due to its lighter sonority which is appreciated in many classical and early romantic works. Trombone music is usually written in concert pitch in either bass or tenor clef, although exceptions do occur, notably in British brass-band music where the tenor trombone is presented as a B♭ transposing instrument, written in treble clef.

A person who plays the trombone is called a trombonist or trombone player.

Construction

|

|

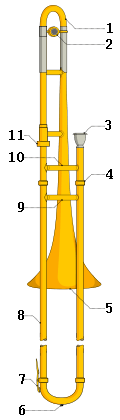

The trombone is a predominantly cylindrical tube bent into an elongated "S" shape. Rather than being completely cylindrical from end to end, the tube is a complex series of tapers with the smallest at the mouthpiece receiver and the largest just before the bell flare. The design of these tapers affects the intonation of the instrument. As with other brass instruments, sound is produced by blowing air through pursed lips producing a vibration that creates a standing wave in the instrument.

The detachable cup-shaped mouthpiece is similar to that of the baritone horn and closely related to that of the trumpet. It has the venturi:[1] a small constriction of the air column that adds resistance greatly affecting the tone of the instrument and is inserted into the mouthpiece receiver in the slide section. The slide section consists of a leadpipe, the inner and outer slide tubes, and the bracing, or "stays". Modern stays are soldered, while sackbuts (medieval precursors to trombones) were made with loose, unsoldered stays.[2][3]

The 'slide', the most distinctive feature of the trombone (cf. valve trombone), allows the player to extend the length of the air column, lowering the pitch. To prevent friction from slowing the action of the slide, additional sleeves known as stockings were developed during the Renaissance. These "stockings" were soldered onto the ends of the inner slide tubes. Nowadays, the stockings are incorporated into the manufacturing process of the inner slide tubes and represent a fractional widening of the tube to accommodate the necessary method of alleviating friction. This part of the slide must be lubricated frequently. Additional tubing connects the slide to the bell of the instrument through a neckpipe, and bell or back bow (U-bend). The joint connecting the slide and bell sections is furnished with a threaded collar to secure the connection of the two parts of the instrument, though older models from the early 20th century and before were usually equipped with friction joints and no ancillary mechanism to tighten the joint.

The adjustment of intonation is most often accomplished with a short tuning slide between the neckpipe and the bell incorporating the bell bow (U-bend); this device was designed by the French maker François Riedlocker during the early 19th century and applied to French and British designs and later in the century to German and American models, though German trombones were built without tuning slides well into the 20th century. However, trombonists, unlike other instrumentalists, are not subject to the intonation issues resulting from valved or keyed instruments, since they can adjust intonation "on the fly" by subtly altering slide positions when necessary. For example, second position "A" is not in exactly the same place on the slide as second position "E". Many types of trombone also include one or more rotary valves used to increase the length of the instrument (and therefore lower its pitch) by directing the air flow through additional tubing. This allows the instrument to reach notes that are otherwise not possible without the valve as well as play other notes in alternate positions.

Like the trumpet, the trombone is considered a cylindrical bore instrument since it has extensive sections of tubing, principally in the slide section, that are of unchanging diameter. Tenor trombones typically have a bore of 0.450 inches (11.4 mm) (small bore) to 0.547 inches (13.9 mm) (large or orchestral bore) after the leadpipe and through the slide. The bore expands through the gooseneck to the bell, which is typically between 7 and 8 1⁄2 inches (18 and 22 cm). A number of common variations on trombone construction are noted below.

History

Etymology

"Trombone" comes from the Italian word tromba (trumpet) plus the suffix -one (big), meaning "big trumpet".

During the Renaissance, the equivalent English term was "sackbut". The word first appears in court records in 1495 as "shakbusshe" at about the time King Henry VII married a Portuguese princess who brought musicians with her. "Shakbusshe" is similar to "sacabuche", attested in Spain as early as 1478. The French equivalent "saqueboute" appears in 1466.[4]

The German "Posaune" long predates the invention of the slide and could refer to a natural trumpet as late as the early fifteenth century.[5]

Origin

Both towns and courts sponsored bands of shawms and trombone. The most famous and influential served the Duke of Burgundy. The trombone's principal role was the contratenor part in a dance band.[6] The sackbut was used extensively across Europe, from its appearance in the 15th century to a decline in most places by the mid-late 17th century. It was used in outdoor events, in concert, and in liturgical settings. With trumpeters, trombonists in German city-states were employed as civil officials. As officials, these trombonists were often relegated to standing watch in the city towers but would also herald the arrival of important people to the city. This is similar to the role of a military bugler and was used as a sign of wealth and strength in 16th century German cities.

However, these trombonists were often viewed separately from the more skilled trombonists who played in groups such as the alta capella wind ensembles and the first orchestral ensembles. These performed in religious settings, such as St Mark's Basilica in Venice in the early 17th century.[7]

Composers who wrote for trombone during this period include Claudio Monteverdi, Heinrich Schütz, Giovanni Gabrieli and his uncle Andrea Gabrieli. The trombone doubled voice parts in sacred works, but there are also solo pieces written for trombone in the early 17th century.

When the sackbut returned to common use in England in the 18th century, Italian music was so influential that the instrument became known as the "trombone",[8] although in some countries the same name has been applied throughout its history, viz. Italian trombone and German Posaune. The 17th-century trombone was built in slightly smaller dimensions than modern trombones and had a bell that was more conical and less flared.

During the later Baroque period, Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frideric Handel used trombones on a few occasions. Bach called for a tromba di tirarsi to double the cantus firmus in some of his liturgical cantatas, which may be a form of the closely related slide trumpet.[9] Bach also employed a choir of four trombones to double the chorus in three of his cantatas (BWV 2, BWV 21 and BWV 38),[10] and also a quartet of three trombones and one cornett in the cantata BWV 25. Handel used it in the Death March from Saul, Samson, and Israel in Egypt. All were examples of an oratorio style popular during the early 18th century. Score notations are rare because only a few professional "Stadtpfeiffer" or alta cappella musicians were available. Handel, for instance, had to import trombones to England from a Royal court in Hanover, Germany, to perform one of his larger compositions. Therefore, trombone parts were rather seldom given "solo" roles that were not interchangeable with other instruments.

Classical period

Christoph Willibald Gluck was the first major composer to use the trombone in an opera overture, Alceste (1767), but he also used it in operas such as Orfeo ed Euridice, Iphigénie en Tauride (1779) and Echo et Narcisse.

The construction of the trombone changed relatively little between the Baroque and Classical period. The most obvious change was in the bell, slightly more flared.

The first use of the trombone as an independent instrument in a symphony was in the Symphony in E♭ (1807) by Swedish composer Joachim Nicolas Eggert.[11] But the composer usually credited with the trombone's introduction into the symphony orchestra was Ludwig van Beethoven in Symphony No. 5 in C minor (1808). Beethoven also used trombones in his Symphony No. 6 in F major ("Pastoral") and Symphony No. 9 ("Choral").

Romantic period

19th-century orchestras

Trombones were often included in compositions, operas, and symphonies by composers such as Felix Mendelssohn, Hector Berlioz, Franz Berwald, Charles Gounod, Franz Liszt, Gioacchino Rossini, Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Giuseppe Verdi, and Richard Wagner among others.

Although the trombone trio had been paired with one or two cornets during the Renaissance and early Baroque periods, the disappearance of the cornet as a partner and replacement by oboe and clarinet left unchanged the trombone's purpose: to support the alto, tenor, and bass voices of the chorus (usually in ecclesiastical settings) where harmonic moving lines were more difficult to pick out than the melodic soprano line. But the introduction of trombones into the orchestra allied them more closely with trumpets, and soon an additional tenor trombone replaced alto. The Germans and Austrians kept alto trombone somewhat longer than the French, who preferred a section of three tenor trombones until after the Second World War. In other countries, the trio of two tenor trombones and one bass became standard by about the mid 19th century.

Trombonists were employed less by court orchestras and cathedrals and so were expected to provide their own instrument. Military musicians were provided with instruments, and instruments like the long F or E♭ bass trombone remained in military use until around the First World War. But orchestral musicians adopted the tenor trombone, the most versatile trombone that could play in the ranges of any of the three trombone parts that typically appeared in orchestral scores.

Valve trombones in the mid-19th century did little to alter the make-up of the orchestral trombone section; although it was ousted from orchestras in Germany and France, the valve trombone remained popular almost to the exclusion of the slide instrument in countries such as Italy and Bohemia. Composers such as Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini, Bedřich Smetana, and Antonín Dvořák scored for a valve trombone section.

With the ophicleide or later, the tuba subjoined to the trombone trio during the 19th century, parts scored for the bass trombone rarely descended as low as parts scored before the addition of either of these new low brass instruments. Only in the early 20th century did it regain a degree of independence. Experiments with the trombone section included Richard Wagner's addition of a contrabass trombone in Der Ring des Nibelungen and Gustav Mahler's and Richard Strauss' augmentation by adding a second bass trombone to the usual trio of two tenor trombones and one bass trombone. The majority of orchestral works are still scored for the usual mid- to late-19th-century low brass section of two tenor trombones, one bass trombone, and one tuba.

19th-century wind bands

Trombones have been a part of the large wind band since its inception as an ensemble during the French Revolution of 1791. During the 19th century wind band traditions were established, including circus bands, military bands, brass bands (primarily in the UK), and town bands (primarily in the US). Some of these, especially military bands in Europe, used rear-facing trombones where the bell section pointed behind the player's left shoulder. These bands played a limited repertoire, with few original compositions, that consisted mainly of orchestral transcriptions, arrangements of popular and patriotic tunes, and feature pieces for soloists (usually cornetists, singers, and violinists). A notable work for wind band is Berlioz's 1840 Grande symphonie funèbre et triomphale, which uses a trombone solo for the entire second movement.

Toward the end of the 19th century, trombone virtuosi began appearing as soloists in American wind bands. The most notable was Arthur Pryor, who played with the John Philip Sousa band and formed his own.

19th-century pedagogy

In the Romantic era, Leipzig became a center of trombone pedagogy. The trombone began to be taught at the Musikhochschule founded by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. The Paris Conservatory and its yearly exhibition also contributed to trombone education. At the Leipzig academy, Mendelssohn's bass trombonist, Karl Traugott Queisser, was the first in a long line of distinguished professors of trombone. Several composers wrote works for Quiesser, including Ferdinand David (Mendelssohn's concertmaster) who wrote in 1837 the Concertino for Trombone and Orchestra, Ernst Sachse and Friedrich August Belcke, whose solo works remain popular in Germany. Queisser helped reestablish the reputation of the trombone in Germany. He championed and popularized Christian Friedrich Sattler's tenorbass trombone during the 1840s, leading to its widespread use in orchestras throughout Germany and Austria.

19th-century construction

Sattler had a great influence on trombone design. He introduced a significant widening of the bore (the most important since the Renaissance), the innovations of Schlangenverzierungen (snake decorations), the bell garland, and the wide bell flare—features still found on German-made trombones that were widely copied during the 19th century.

The trombone was further improved in the 19th century with the addition of "stockings" at the end of the inner slide to reduce friction, the development of the water key to expel condensation from the horn, and the occasional addition of a valve that, intentionally, only was to be set on or off but later was to become the regular F-valve. Additionally, the valve trombone came around the 1850s shortly after the invention of valves, and was in common use in Italy and Austria in the second half of the century.

Twentieth century

20th-century orchestras

In the 20th century the trombone maintained its important place in the orchestra in works by Béla Bartók, Alban Berg, Leonard Bernstein, Benjamin Britten, Aaron Copland, Edward Elgar, George Gershwin, Gustav Holst, Leos Janacek, Gustav Mahler, Olivier Messiaen, Darius Milhaud, Carl Nielsen, Sergei Prokofiev, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Maurice Ravel, Ottorino Respighi, Arnold Schoenberg, Dmitri Shostakovich, Jean Sibelius, Richard Strauss, Igor Stravinsky, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Heitor Villa-Lobos, and William Walton.

With the rise of recorded music and music schools, orchestral trombone sections around the world began to have a more consistent idea of a standard trombone sound. British orchestras abandoned the use of small bore tenors and G basses in favor of an American/German approach of large bore tenors and B♭ basses in the 1940s. French orchestras did the same in the 1960s.

20th-century wind bands

During the first half of the century, touring and community concert bands lost their popularity in the United States and were greatly reduced in number. However, with the development of music education in the public school system, high school, and university concert bands and marching bands and became ubiquitous in the US. A typical concert band trombone section consists of two tenor trombones and one bass trombone, but using multiple players per part is common practice, especially in public-school settings.

Use in jazz

In the 1900s the trombone assisted the bass or tuba player's job of outlining chords for the other instruments by playing a bass line for the higher-pitched instruments to improvise over. It was not until the swing era of the mid-1920s that the trombone began to be used as a solo instrument. Examples of early trombone soloists are Jack Teagarden and J.J. Johnson.[12][13]

20th-century construction

Changes in construction have occurred during the 20th century, such as the use of different materials; increases in mouthpiece, bore, and bell dimensions; and in types of mutes and valves. Despite the universal switch to a larger horn, many European trombone makers prefer a slightly smaller bore than their American counterparts.

One of the most significant changes is the popularity of the F-Attachment trigger. Through the mid-20th century, orchestral trombonists used instruments that lacked a trigger because there was no need for one. But as 20th century composers such as Mahler became popular, tenor trombone parts began to extend down into lower ranges that required a trigger. Although some trombonists prefer "straight" trombone models without triggers, most have added them for convenience and versatility.

Contemporary use

The trombone can be found in symphony orchestras, concert bands, marching bands, military bands, brass bands, and brass choirs. In chamber music, it is used in brass quintets, quartets, or trios, or trombone trios, quartets, or choirs. The size of a trombone choir can vary from five or six to twenty or more members. Trombones are also common in swing, jazz, merengue, salsa, R&B, ska, and New Orleans brass bands.

Types

The most frequently encountered type of trombone today is the tenor, followed by the bass, though as with many other Renaissance instruments the trombone has been built in sizes from piccolo to contrabass. Trombones are usually constructed with a slide that is used to change the pitch. Valve trombones use three valves (singly or in combination) instead of the slide. The valves follow the same schema as other valved instruments-the first valve lowers the pitch by one step, the second valve by a half-step, and the third valve by one and a half steps.

A superbone uses a full set of valves and a slide. These differ from trombones with triggers. Some slide trombones have one or (less frequently) two rotary valves operated by a left-hand thumb trigger. The single rotary valve is part of the F attachment, which adds a length of tubing to lower the instrument's fundamental pitch from B♭ to F. Some bass trombones have a second trigger with a different length of tubing. The second trigger facilitates playing the otherwise problematic low B. A buccin is a trombone with a round, zoomorphic bell section. They were common in 19th-century military bands.

Technique

Basic slide positions

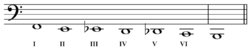

The modern system has seven chromatic slide positions on a tenor trombone in B♭. It was first described by Andre Braun circa 1795.[14]

In 1811 Joseph Fröhlich wrote on the differences between the modern system and an old system where four diatonic slide positions were used and the trombone was usually keyed to A.[15] To compare between the two styles the chart below may be helpful (take note for example, in the old system contemporary 1st-position was considered "drawn past" then current 1st).[15] In the modern system, each successive position outward (approximately 3 1⁄4 inches [8 cm]) will produce a note which is one semitone lower when played in the same partial. Tightening and loosening the lips will allow the player to "bend" the note up or down by a semitone without changing position, so a slightly out-of-position slide may be compensated for by ear.

| New system | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old system | – | 1 | – | 2 | – | 3 | 4 |

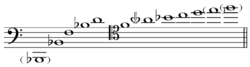

Partials and intonation

As with all brass instruments, progressive tightening of the lips and increased air pressure allow the player to move to different partial in the harmonic series. In the first position (also called closed position) on a B♭ trombone, the notes in the harmonic series begin with B♭2 (one octave higher than the pedal B♭1), F3 (a perfect fifth higher than the previous partial), B♭3 (a perfect fourth higher), D4 (a major third higher), and F4 (a minor third higher).

F4 marks the sixth partial, or the fifth overtone. Notes on the next partial, for example A♭4 (a minor third higher) in first position, tend to be out of tune in regards to the twelve-tone equal temperament scale. A♭4 in particular, which is at the seventh partial (sixth overtone) is nearly always 31 cents, or about one third of a semitone, flat of the minor seventh. On the slide trombone, such deviations from intonation are corrected for by slightly adjusting the slide or by using an alternate position.[16] Although much of Western music has adopted the even-tempered scale, it has been the practice in Germany and Austria to play these notes in position, where they will have just intonation (see harmonic seventh as well for A♭4).

The next higher partials—B♭4 (a major second higher), C5 (a major second higher), D5 (a major second higher)—do not require much adjustment for even-tempered intonation, but E♭5 (a minor second higher) is almost exactly a quarter tone higher than it would be in twelve-tone equal temperament. E♭5 and F5 (a major second higher) at the next partial are very high notes; a very skilled player with a highly developed facial musculature and diaphragm can go even higher to G5, A♭5, B♭5 and beyond.

The higher in the harmonic series any two successive notes are, the closer they tend to be (as evidenced by the progressively smaller intervals noted above). A byproduct of this is the relatively few motions needed to move between notes in the higher ranges of the trombone. In the lower range, significant movement of the slide is required between positions, which becomes more exaggerated on lower pitched trombones, but for higher notes the player need only use the first four positions of the slide since the partials are closer together, allowing higher notes in alternate positions. As an example, F4 (at the bottom of the treble clef) may be played in first, fourth or sixth position on a B♭ trombone. The note E1 (or the lowest E on a standard 88-key piano keyboard) is the lowest attainable note on a 9-foot (2.7 m) B♭ tenor trombone, requiring a full 7 feet 4 inches (2.24 m) of tubing. On trombones without an F attachment, there is a gap between B♭1 (the fundamental in first position) and E2 (the first harmonic in seventh position). Skilled players can produce "falset" notes between these, but the sound is relatively weak and not usually used in performance. The addition of an F attachment allows for intermediate notes to be played with more clarity.

Pedal tones

The pedal tone on B♭ is frequently seen in commercial scoring but much less often in symphonic music while notes below that are called for only rarely as they "become increasingly difficult to produce and insecure in quality" with A♭ or G being the bottom limit for most tenor trombonists.[16] Some contemporary orchestral writing, movie or video game scoring, trombone ensemble and solo works will call for notes as low as a pedal C, B, or even double pedal B♭ on the bass trombone.

Glissando

The trombone is one of the few wind instruments that can produce a true glissando, by moving the slide without interrupting the airflow or sound production. Every pitch in a glissando must have the same harmonic number, and a tritone is the largest interval that can be performed as a glissando.[16]:151

'Harmonic', 'inverted', 'broken' or 'false' glissandos are those that cross one or more harmonic series, requiring a simulated or faked glissando effect.[17]

Trills

Trills, though generally simple with valves, are difficult on the slide trombone. Trills tend to be easiest and most effective higher in the harmonic series because the distance between notes is much smaller and slide movement is minimal. For example, a trill on B♭3/C4 is virtually impossible as the slide must move two positions (either 1st-to-3rd or 5th-to-3rd), however at an octave higher (B♭4/C5) the notes can both be achieved in 1st position as a lip trill. Thus, the most convincing trills tend to be above the first octave and a half of the tenor's range.[18] Trills are most commonly found in early Baroque and Classical music for the trombone as a means of ornamentation, however, some more modern pieces will call for trills as well.

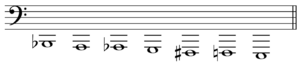

Notation

Unlike most other brass instruments in an orchestral setting, the trombone is not usually considered a transposing instrument. Prior to the invention of valve systems, most brass instruments were limited to playing one overtone series at a time; altering the pitch of the instrument required manually replacing a section of tubing (called a "crook") or picking up an instrument of different length. Their parts were transposed according to which crook or length-of-instrument they used at any given time, so that a particular note on the staff always corresponded to a particular partial on the instrument. Trombones, on the other hand, have used slides since their inception. As such, they have always been fully chromatic, so no such tradition took hold, and trombone parts have always been notated at concert pitch (with one exception, discussed below). Also, it was quite common for trombones to double choir parts; reading in concert pitch meant there was no need for dedicated trombone parts. Note that while the fundamental sounding pitch (slide fully retracted) has remained quite consistent, the conceptual pitch of trombones has changed since their origin (e.g. Baroque A tenor = modern B-flat tenor).[19]

Trombone parts are typically notated in bass clef, though sometimes also written in tenor clef or alto clef. The use of alto clef is usually confined to orchestral first trombone parts, with the second trombone part written in tenor clef and the third (bass) part in bass clef. As the alto trombone declined in popularity during the 19th century, this practice was gradually abandoned and first trombone parts came to be notated in the tenor or bass clef. Some Russian and Eastern European composers wrote first and second tenor trombone parts on one alto clef staff (the German Robert Schumann was the first to do this). Examples of this practice are evident in scores by Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Dmitri Shostakovich. Trombone parts in band music are nearly exclusively notated in bass clef. The rare exceptions are in contemporary works intended for high-level wind bands.

An accomplished performer today is expected to be proficient in reading parts notated in bass clef, tenor clef, alto clef, and (more rarely) treble clef in C, with the British brass-band performer expected to handle treble clef in B♭ as well.

Mutes

A variety of mutes can be used with the trombone to alter its timbre. Many are held in place with the use of cork grips, including the straight, cup, harmon and pixie mutes. Some fit over the bell, like the bucket mute. In addition to this, mutes can be held in front of the bell and moved to cover more or less area for a wah-wah effect. Mutes used in this way include the "hat" (a metal mute shaped like a bowler hat) and plunger (which looks like, and often is, the rubber suction cup from a sink or toilet plunger), a sound featured as the voices of adults in the Peanuts cartoons.

Variations in construction

Bells

Trombone bells (and sometimes slides) may be constructed of different brass mixtures. The most common material is yellow brass (70% copper, 30% zinc), but other materials include rose brass (85% copper, 15% zinc) and red brass (90% copper, 10% zinc). Some manufacturers offer interchangeable bells. Tenor trombone bells are usually between 7 and 9 in (18–23 cm) in diameter, the most common being sizes from 7 1⁄2 to 8 1⁄2 in (19–22 cm). The smallest sizes are found in small jazz trombones and older narrow-bore instruments, while the larger sizes are common in orchestral models. Bass trombone bells can be as large as 10 1⁄2 in (27 cm) or more, though usually either 9 1⁄2 or 10 in (24 or 25 cm) in diameter. The bell may be constructed out of two separate brass sheets or out of one single piece of metal and hammered on a mandrel until the part is shaped correctly. The edge of the bell may be finished with or without a piece of bell wire to secure it, which also affects the tone quality; most bells are built with bell wire. Occasionally, trombone bells are made from solid sterling silver.

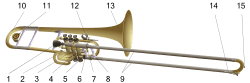

Valve attachments

Many trombones have valve attachments to aid in increasing the range of the instrument while also allowing alternate slide positions for difficult music passages. In addition, valve attachments make trills much easier. Valve attachments appear on alto, tenor, bass, and contrabass trombones. It is rare on the alto, but when the instrument does have it, the valve attachment changes the key of the instrument from E♭ to B♭, allowing the alto trombone to play in the tenor trombone range. Tenor trombones commonly have valve attachments, the most common being the F-attachment, which changes the pitch of the instrument from B♭ to F, increasing the range of the instrument downward and allowing alternate slide positions for notes in 6th or 7th position.

Bass trombones also very commonly have F-attachments, which serve exactly the same function as on the tenor trombone. Some single valve bass trombones have E-attachments instead of F-attachments, or sometimes there is extra tubing on the F-attachment to allow it to be used as an E-attachment if desired. However, many bass trombones have a second valve attachment instead, which increases their range downward even more. The most common second valve attachment is the G♭-attachment, which changes the instrument's key to D when used in combination with the F-attachment (or D♭ if used with the less common E-attachment). There are other configurations other than the G♭-attachment however.

The two valves on a bass trombone can either be independent or dependent. Double rotor dependent valve bass trombones were created in the late 1950s, and double rotor independent valve bass trombones were created in the late 1960s/early 1970s. Dependent means that the second valve only works when used in combination with the first, as it is located directly on the F- or E-attachment tubing. Newer bass trombones have independent (in-line) valves instead, meaning that the second valve is located on the neckpipe of the instrument and can therefore operate independently of the other.[20] Contrabass trombones also can have valve attachments. Contrabass trombones in the key of F typically have two valves tuned to C and D♭ respectively. Contrabass trombones in B♭ on the other hand typically only have one valve, which is tuned to F, though some have a second valve tuned to G♭.

The most common type of valve seen for valve attachments is the rotary valve. Some trombones have piston valves used instead of rotary valves for valve attachments, but it is very rare and is today considered unconventional. Many variations of the rotary valve have been invented in the past half-century, such as the Thayer valve (or axial flow valve), the Hagmann valve, the Greenhoe rotor, and several others, all of which were designed to give the trombone a more open, free sound than a conventional rotary valve would allow due to the 90° bend in most conventional rotary valve designs. Many of these new trombone valve designs have enjoyed great success on the market, but the standard rotary valve remains the most common for trombone valve attachments.

The Thayer valve is an advanced, conically shaped rotary valve that has become very popular in recent trombone design due to the open air flow it allows. The Thayer valve bends the air flowing through the trombone as little as 25 degrees.

The Thayer valve is an advanced, conically shaped rotary valve that has become very popular in recent trombone design due to the open air flow it allows. The Thayer valve bends the air flowing through the trombone as little as 25 degrees. The Hagmann valve is a rotary valve variation that has become popular in recent years. It was invented following the Thayer valve as a response to maintenance issues of the Thayer valve.

The Hagmann valve is a rotary valve variation that has become popular in recent years. It was invented following the Thayer valve as a response to maintenance issues of the Thayer valve. The standard rotary valve, like the one seen on this tenor trombone, is the most common valve type seen on slide trombones today.

The standard rotary valve, like the one seen on this tenor trombone, is the most common valve type seen on slide trombones today.

Valves

Some trombones have valves instead of a slide (see valve trombone). These are usually rotary valves, or piston valves.

A valve trombone

A valve trombone A military 6-valve trombone, by Adolphe Sax. Paris, 1866

A military 6-valve trombone, by Adolphe Sax. Paris, 1866

Tubing

More often than not, tenor trombones with an F attachment, or trigger, have a larger bore through the attachment than through the 'straight' section (the portion of the trombone through which the air flows when the attachment is not engaged). Typically, for orchestral instruments, the slide bore is 0.547 in (13.9 mm) and the attachment tubing bore is 0.562 in (14.3 mm). A wide variety of valve attachments and combinations are available. Valve attachment tubing usually incorporates a small tuning slide so that the attachment tubing can be tuned separately from the rest of the instrument. Most B♭/F tenor and bass trombones include a tuning slide long enough to lower the pitch to E with the valve tubing engaged, enabling the production of B2.

Whereas older instruments fitted with valve attachments usually had the tubing coiled rather tightly in the bell section (closed wrap or traditional wrap), modern instruments usually have the tubing kept as free as possible of tight bends in the tubing (open wrap), resulting in a freer response with the valve attachment tubing engaged. While open-wrap tubing does offer a more open sound, the tubing sticks out from behind the bell and is more vulnerable to damage. For that reason, closed-wrap tubing remains more popular in trombones used in marching bands or other ensembles where the trombone may be more prone to damage.

Tuning

Some trombones are tuned through a mechanism in the slide section rather than via a separate tuning slide in the bell section. This method preserves a smoother expansion from the start of the bell section to the bell flare. The tuning slide in the bell section requires two portions of cylindrical tubing in an otherwise conical part of the instrument, which affects the tone quality. Tuning the trombone enables it to play with other instruments which is essential for the trombone.

Slides

Common and popular bore sizes for trombone slides are 0.500, 0.508, 0.525 and 0.547 in (12.7, 12.9, 13.3 and 13.9 mm) for tenor trombones, and 0.562 in (14.3 mm) for bass trombones. The slide may also be built with a dual-bore configuration, in which the bore of the second leg of the slide is slightly larger than the bore of the first leg, producing a stepwise conical effect. The most common dual-bore combinations are 0.481–0.491 in (12.2–12.5 mm), 0.500–0.508 in (12.7–12.9 mm), 0.508–0.525 in (12.9–13.3 mm), 0.525–0.547 in (13.3–13.9 mm), 0.547–0.562 in (13.9–14.3 mm) for tenor trombones, and 0.562–0.578 in (14.3–14.7 mm) for bass trombones.

Mouthpiece

The mouthpiece is a separate part of the trombone and can be interchanged between similarly sized trombones from different manufacturers. Available mouthpieces for trombone (as with all brass instruments) vary in material composition, length, diameter, rim shape, cup depth, throat entrance, venturi aperture, venturi profile, outside design and other factors. Variations in mouthpiece construction affect the individual player's ability to make a lip seal and produce a reliable tone, the timbre of that tone, its volume, the instrument's intonation tendencies, the player's subjective level of comfort, and the instrument's playability in a given pitch range.

Mouthpiece selection is a highly personal decision. Thus, a symphonic trombonist might prefer a mouthpiece with a deeper cup and sharper inner rim shape in order to produce a rich symphonic tone quality, while a jazz trombonist might choose a shallower cup for brighter tone and easier production of higher notes. Further, for certain compositions, these choices between two such performers could easily be reversed. Some mouthpiece makers now offer mouthpieces that feature removable rims, cups, and shanks allowing players to further customize and adjust their mouthpieces to their preference.

Plastic

Instruments made mostly from plastic, including the pBone and the Tromba plastic trombone, emerged in the 2010s as a cheaper and more robust alternative to brass.[21][22] Plastic instruments could come in almost any colour but the sound plastic instruments produce is different from that of brass. While originally seen as a gimmick, these plastic models have found increasing popularity of the last decade and are now viewed as practice tools that make for more convenient travel as well as a cheaper option for beginning players not wishing to invest so much money in a trombone right away. Manufacturers now produce large-bore models with triggers as well as smaller alto models.

Regional variations

Germany and Austria

German trombones have been built in a wide variety of bore and bell sizes. The traditional German Konzertposaune can differ substantially from American designs in many aspects. The mouthpiece is typically rather small and is placed into a slide section with a very long leadpipe of at least 12 to 24 inches (30–60 cm). The whole instrument is often made of gold brass, and its sound is usually darker compared with British, French or American designs. While their bore sizes were considered large in the 19th century, German trombones have altered very little over the last 150 years and are now typically somewhat smaller than their American counterparts. Bell sizes remain very large in all sizes of German trombone and a bass trombone bell may exceed 10 inches (25 cm) in diameter.

Valve attachments in tenor and bass trombones were first seen in the mid 19th century, originally on the tenor B♭ trombone. Before 1850, bass trombone parts were mostly played on a slightly longer F-bass trombone (a fourth lower). The first valve was simply a fourth-valve, or in German "Quart-ventil", built onto a B♭ tenor trombone, to allow playing in low F. This valve was first built without a return spring, and was only intended to set the instrument in B♭ or F for extended passages. Since the mid-20th century, modern instruments use a trigger to engage the valve while playing.

As with other German and Austrian brass instruments, rotary valves are used to the exclusion of almost all other types of valve, even in valve trombones. Other features often found on German trombones include long water keys and snake decorations on the slide and bell U-bows.

Since around 1925, when jazz music became popular, Germany has been selling "American trombones" as well. Most trombones played in Germany today, especially by amateurs, are built in the American fashion, as those are much more widely available, and thus far cheaper.

France

French trombones were built in the very smallest bore sizes up to the end of the Second World War and whilst other sizes were made there, the French usually preferred the tenor trombone to any other size. French music, therefore, usually employed a section of three tenor trombones up to the mid–20th century. Tenor trombones produced in France during the 19th and early 20th centuries featured bore sizes of around 0.450 in (11.4 mm), small bells of not more than 6 in (15 cm) in diameter, as well as a funnel-shaped mouthpiece slightly larger than that of the cornet or horn. French tenor trombones were built in both C and B♭, altos in D♭, sopranos in F, piccolos in high B♭, basses in G and E♭, contrabasses in B♭.

Didactics

Several makers have begun to market compact B♭/C trombones that are especially well suited for young children learning to play the trombone who cannot reach the outer slide positions of full-length instruments. The fundamental note of the unenhanced length is C, but the short valved attachment that puts the instrument in B♭ is open when the trigger is not depressed. While such instruments have no seventh slide position, C and B natural may be comfortably accessed on the first and second positions by using the trigger. A similar design ("Preacher model") was marketed by C.G. Conn in the 1920s, also under the Wurlitzer label. Currently, B♭/C trombones are available from many manufacturers, including German makers Günter Frost, Thein and Helmut Voigt, as well as the Yamaha Corporation.[23]

Manufacturers

Trombones in slide and valve configuration have been made by a vast array of musical instrument manufacturers. For the brass bands of the late 19th and early 20th century, prominent American manufacturers included Graves and Sons, E. G. Wright and Company, Boston Musical Instrument Company, E. A. Couturier, H. N. White Company/King Musical Instruments, J. W. York, and C.G. Conn. In the 21st century, leading mainstream manufacturers of trombones include Vincent Bach, Conn, Courtois, Edwards, Getzen, Greenhoe, Jupiter, Kanstul, King, Michael Rath, Schilke, S.E. Shires, Thein and Yamaha.

See also

- Aequale

- Shout band

- Tromboon – experimental musical instrument, hybrid of trombone and bassoon

References

- Friedman, Jay. "The German Trombone, by Jay Friedman". Friedmann. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- Campbell, Murray; Greated, Clive A.; Myers, Arnold (2004). Musical Instruments: History, Technology, and Performance of Instruments of Western Music. Oxford University Press. pp. 201–. ISBN 978-0-19-816504-0. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- Fischer, Henry George (1984). The Renaissance Sackbut and Its Use Today. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-0-87099-412-8. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- Michault, Pierre. "Le doctrinal du temps présent , compilé par maistre Pierre Michault, secrétaire du très puissant duc de Bourgoingne". gallica.bnf.fr (in French). p. 16. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- Guion, David M. (2010). A History of the Trombone. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 22. ISBN 9780810874459.

- Herbert (2006), p. 59.

- Green, Helen (2011). "Defining the City 'Trumpeter': German Civic Identity and the Employment of Brass Instruments, c. 1500". Journal of the Royal Musical Association.

- Guion, David (1988). The Trombone: Its History and Music, 1697–1811. Gordon and Breach. p. 3. ISBN 2-88124-211-1.

Many modern musicians prefer to use the word 'sackbut' when referring to the Baroque trombone. All other instruments in constant use since the Baroque have changed more...In response to the number of times people including musicians, have asked if the sackbut is something like a trombone, I have stopped using this misleading word.

- Lewis, Horace (1 January 1975). "The Problem of the Tromba Da Tirarsi in the Works of J. S. Bach". LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Weiner, Harold. "The Soprano Trombone Hoax" (PDF). Historical Brass Society Journal. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Kallai, Avishai. "Biography of Joachim Nikolas Eggert". Musicalics. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014.

- Bernotas, Bob (7 September 2015). "Trombone". All About Jazz. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- Wilken, David. "The Historical Evolution of the Jazz Trombone: Part One". trombone.org. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- Weiner, H. (1993). "André Braun's Gamme et Méthode pour les Trombonnes: The Earliest Modern Trombone Method Rediscovered". Historic Brass Society Journal: 288–308.

- Guion (1988), p. 93.

- Kennan, Kent; Grantham, Donald (2002). The Technique of Orchestration. pp. 148–149. ISBN 0-13-040771-2.

- Herbert, Trevor. The Trombone. Yale University Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-300-10095-7.

- Herbert (2006), p. 43.

- Palm, Paul W. "Baroque Solo and Homogeneous Ensemble Trombone Repertoire: A Lecture Recital Supporting and Demonstrating Performance at a Pitch Standard Derived from Primary Sources and Extant Instruments". Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- Douglas Yeo FAQ: Bass Trombone Valve Systems

- Flynn, Mike (20 June 2013). "pBone plastic trombone". Jazzwise Magazine. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- "Korg UK takes on distribution of Tromba". Musical Instrument Professional. 2 May 2013. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- Yamaha Catalog YSL-350C with ascending Bb/C rotor

Further reading

- Adey, Christopher (1998). Orchestral Performance. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-17724-7.

- Baines, Anthony (1980). Brass Instruments: Their History and Development. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-11571-3.

- Bate, Philip (1978). The Trumpet and Trombone. London: Ernest Benn. ISBN 0-510-36413-6.

- Blatter, Alfred (1997). Instrumentation and Orchestration. Belmont: Schirmer. ISBN 0-534-25187-0.

- Blüme, Friedrich, ed. (1962). Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Kassel: Bärenreiter.

- Carter, Stewart (2011). The Trombone in the Renaissance: A History in Pictures and Documents. Bucina: The Historic Brass Society Series. Hillsdale, N.Y.: Pendragon Press. ISBN 978-1-57647-206-4.

- Del Mar, Norman (1983). Anatomy of the Orchestra. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-520-05062-2.

- Gregory, Robin (1973). The Trombone: The Instrument and its Music. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-08816-3.

- Herbert, Trevor; Wallace, John, eds. (1997). The Cambridge Companion to Brass Instruments. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56522-7.

- Kunitz, Hans (1959). Die Instrumentation: Teil 8 Posaune. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. ISBN 3-7330-0009-9.

- Lavignac, Albert, ed. (1927). Encyclopédie de la musique et Dictionnaire du Conservatoire. Paris: Delagrave.

- Maxted, George (1970). Talking about the Trombone. London: John Baker. ISBN 0-212-98360-1.

- Montagu, Jeremy (1979). The World of Baroque & Classical Musical Instruments. New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-089-7.

- Montagu, Jeremy (1976). The World of Medieval & Renaissance Musical Instruments. New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-045-5.

- Montagu, Jeremy (1981). The World of Romantic & Modern Musical Instruments. London: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7994-1.

- Palm, Paul W. (2010) "Baroque Solo and Homogeneous Ensemble Trombone Repertoire: A Lecture Recital Supporting and Demonstrating Performance at a Pitch Standard Derived from Primary Sources and Extant Instruments." DMA thesis, University of North Carolina-Greensboro.

- Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). Grove. ISBN 0-19-517067-9.

- Wick, Denis (1984). Trombone Technique. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-322378-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trombones. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Trombone History Timeline by Will Kimball, Professor of Trombone at Brigham Young University

- International Trombone Association

- Online Trombone Journal

- Acoustics of Brass Instruments from Music Acoustics at the University of New South Wales

- Sources for the Prescribed Sheet Music for the ABRSM practical exams

- Two Frequencies Trombone

- NPR story about trombone bands (2003)

- Overview of trombones on the MIMO (Musical Instrument Museums Online) portal

Slide positions

- Christian E. Waage (2009). "Slide Position Chart", YeoDoug.com

- Antonio J. García. (1997). "Choosing Alternate Positions for Bebop Lines", GarciaMusic.com.