Trinity Chain Pier

Trinity Chain Pier, originally called Trinity Pier of Suspension,[nb 1] was built in Trinity, Edinburgh, Scotland in 1821. The pier was designed by Samuel Brown, a pioneer of chains and suspension bridges. It was intended to serve ferry traffic on the routes between Edinburgh and the smaller ports around the Firth of Forth, and was built during a time of rapid technological advance. It was well used for its original purpose for less than twenty years before traffic was attracted to newly developed nearby ports, and it was mainly used for most of its life for sea bathing. It was destroyed by a storm in 1898; a building at the shore end survives, much reconstructed, as a pub and restaurant called the Old Chain Pier.

The pier | |

| Type | Ferry pier |

|---|---|

| Carries | Passengers |

| Spans | Firth of Forth |

| Locale | Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Designer | Samuel Brown |

| Owner | Trinity Pier Company |

| Total length | 700 feet (210 m) |

| Width | 4 feet (1.2 m) |

| Opening date | 14 August 1821 |

| Closure date | 18 October 1898 |

| Coordinates | 55.980192°N 3.204438°W |

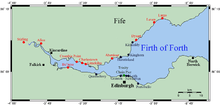

Map of the Firth of Forth showing (in red) some of the destinations served from the pier in its heyday | |

Background

The Firth of Forth is an estuary[nb 2] which separates Edinburgh, Scotland's capital, from the peninsula of Fife. Traffic across the firth has been important for centuries;[nb 3] as well as having industry and agriculture, Fife lies on the shortest route from Edinburgh to the north of the country. The closest bridge to Edinburgh for many years was at Stirling, 36 miles (58 km) to the west.[6] Queensferry, 10 miles (16 km) west, was named after Queen Margaret who crossed by ferry from there in 1070.[7] Traffic across the firth was regulated and taxed as early as 1467, and was historically centred on the route from Leith to Kinghorn. A ferry from Newhaven to Burntisland started in 1792.[6] Travel by sailing boat and stagecoach was slow and unreliable; Walter Scott in The Antiquary (1816) described the journey from Edinburgh to cross at Queensferry as being "like a fly through a glue-pot".[8][9]

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw a series of revolutions in transport during the Industrial Revolution. Turnpike trusts built over 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of roads in Scotland between 1790 and 1810.[10] The Forth and Clyde (1790) and the Union Canals (1822) carried cargo between the west and east coasts, but horse-drawn canal boats were too slow to provide much advance for passengers.[11][nb 4] The steamboat was pioneered in the Firth of Clyde and Glasgow to the west,[nb 5] and made sea travel faster and more predictable for coastal and island communities.[16] Trinity Chain Pier was built because the popularity of the new steam-powered vessels had caused congestion at Leith and Newhaven,[17] and sandbars had built up at both harbours, restricting access at low tide.[18] It was deemed easier to build a new facility than to negotiate more space at Newhaven harbour.[19]

Design

The pier was proposed by Lieutenant George Crichton of the London, Leith, Edinburgh and Glasgow Steam Navigation Company.[17] In 1820 the Lord Provost and magistrates of Edinburgh granted the company permission for the pier's construction.[20] The company then transferred the permission to the Trinity Pier Company who were to administer construction and operate the pier,[19] and they in turn commissioned Captain Samuel Brown to design the pier as his first independent project.[21] Alexander Scott WS, one of the trustees of the company, granted permission to build the pier on his land.[22] Scott and Alexander Stevenson were directors of the Trinity Pier Company, and Crichton was treasurer.[23] It cost £4000 to build.[24][nb 6]

Brown (1776–1852) was a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars and had taken part in the capture of a superior French ship in 1805.[26] He patented his method of building suspension bridges in 1817.[27] He designed the extant 1820 Union Bridge near Berwick-upon-Tweed, which was the biggest suspension bridge in the world when built,[21] and the first in Britain to carry vehicles.[28]

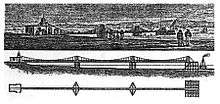

While serving in the Royal Navy, Brown had experimented with using chain instead of rope in rigging sailing ships, and in 1808 he patented a new kind of wrought-iron chain. He sold the design to the Admiralty, which used it as anchor cable on ships.[27] Brown considered that using piles to support a pier was superior to the traditional method of building in stone, because it was more economical to build and easier for ships to dock with. He cited pile-supported piers at Yarmouth, Ostend and Kronstadt which had been successful for long periods based on this design.[29] Brown had used chains in his designs for some of Britain's first suspension bridges; he realised that chains made out of eye bolts joined together were stronger than traditional designs based on shorter links.[21] He was regarded as a "leading promoter" of suspension bridges.[27] He proposed that suspension piers could support military and rescue operations.[30] On 14 August 1822 Brown married Mary Horne from Edinburgh.[31] After the pier at Trinity he went on to build the similar but much larger Royal Suspension Chain Pier in Brighton in 1823. It was destroyed by a storm in 1896.[32]

The pier was 700 feet (210 m) long[33] with a 4-foot-wide (1.2 m) passenger deck. This comprised three 209-foot-long (64 m) wooden spans suspended 10 feet (3.0 m) above high water from lengths of wrought-iron chain connecting cast-iron standards to the shore. Each standard was in the shape of an arch which the passengers walked through.[33][34] By 1838 the passenger deck had rails fitted to assist in moving large items of luggage.[35] The chain was made of eye bolts about 10 feet (3.0 m) long, which, uniquely among Brown's designs, varied in thickness according to the load they were expected to carry.[36][37][nb 7] The long eye bolts were joined by shorter linking plates,[38] and hung in a catenary 14 feet (4.3 m) from the tops of the standards.[39] The chains crossed the standards on cast-iron saddles.[40] The three seaward standards were built on platforms[nb 8] anchored to wooden piles driven into the foreshore. The largest platform, which formed the head of the pier, was 60 feet (18 m) by 50 feet (15 m), and covered in 2-inch (51 mm) thick planks.[33] The length of the pier head was extended to 70 feet (21 m) prior to November 1821.[23] It was supported on 46 piles driven 8 feet (2.4 m) into the clay seabed.[41] At the landward end the chain passed over a solid masonry construction, 6 feet (1.8 m) square and 20 feet (6.1 m) high,[nb 9] and was then anchored at a 45° angle 10 feet (3.0 m) into the hard clay soil. The seaward end of the chain went over the outer piles at the same angle, and the piles were braced with diagonal supports to take the sideways load.[33] There was a 4-foot-high (1.2 m) wrought-iron railing along the length of the deck,[39] straight diagonal members connecting the deck to the standards, and iron bracing under the deck. The pier was designed for passenger use only, and moved noticeably when walked on.[12][34][40]

Brown tested the pier on 21 September 1821 by having 21 tons of pig-iron ballast placed on the spans[42] while it was in use by passengers.[23][29][43] The French engineer Claude-Louis Navier inspected the pier in 1821, and reported that the structure was strengthened against wind loads in 1822, following its behaviour during storms in its first winter.[44]

History

Ferry pier

Poor weather delayed the driving of the piles, which took from March to July 1821.[33] The pier was decorated with flags for its opening ceremony on 14 August.[45] Steamboats fired salutes from alongside the pier. Three hundred people walked from the Trinity Hotel to the pier, and boarded a steamboat for a brief excursion, while a band played from a second vessel. The opening was attended by the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, the local magistrates, as well as Crichton, Ramsay, Scott, Stevenson, and the other proprietors of the company.[46] Admiral Robert Otway (commander-in-chief of naval forces at Leith), General Duff, Sir George Mackenzie, George Baird (the Principal of Edinburgh University), Robert Jameson, John Leslie, William Wallace, and Brown the designer were also present. When they returned they took refreshment in a tent at the head of the pier.[47]

The pier served ferry traffic between Edinburgh and ports on the Firth of Forth and beyond, and was usable at all states of the tide.[46] Leith and Newhaven were having problems with sandbars leading to vessels being trapped and damaged at low water, but the Chain Pier had 6 feet 8 inches (2.03 m) of water at the very lowest tides,[18] and could serve vessels when Leith and Newhaven were unable to.[48] In its first year the pier made a profit of £200,[49][nb 10] and there was a proposal to improve the facilities for passengers and other visitors, including having telescopes to view the ferries. Traffic from as far afield as Aberdeen and London was mentioned, and the pier was referred to as "ingenious and beautiful".[51] By late 1823 there was a small shop at the pier head.[52]

In 1822 the organisers of King George IV's visit to Edinburgh considered using the pier for his landing, but following protests they chose Leith harbour instead.[53] The "New Cut" was built for the proposed royal parade from the Chain Pier to the city centre; it later became Craighall Road.[54] In the same year, the Brilliant became the first steam packet to call at Anstruther, en route from the Chain Pier to Aberdeen.[55]

The existing ferry operators tried to maintain their monopoly over the shortest crossings to Fife for several years. Ferries from the Chain Pier were prevented from landing at Dysart, Kirkcaldy, Aberdour and all ports in between. This was confirmed in a court hearing in December 1821, in which the existing interdict on ferries from the pier to Kirkcaldy was maintained and extended.[56] This was seen as being detrimental to the quality of service.[57] By August 1829 ferries to Dysart were permitted, and a flag was raised at the Chain Pier in celebration.[58] Ferries to Grangemouth connected with the Forth and Clyde Canal.[12]

In 1823 the piles were discovered to be under attack from the marine crustacean Limnoria terebrans, informally referred to as the 'gribble worm'.[59] It was about 1⁄6 inch (4.2 mm) long, and bored holes in the piles, reducing their strength.[60] After many attempts to secure and repair them, in 1830 the piles had to be replaced and sheathed in iron.[49] James Anderson accomplished the difficult and dangerous task of replacing the timbers while maintaining the tension in the chains to keep the bridge standing.[61][62][nb 11] The costs involved put the company into debt and prevented the payment of a dividend.[49]

In mid-1830 the Royal George carried 8,168 passengers to Dysart, Leven and Largo in a two-month period, as well as 1,181 pleasure trippers who did not land in Fife.[63] In 1831 the Victory and Lady of the Lake made daily sailings from the Chain Pier to the same destinations. The lowest fare to Largo was 2 shillings.[nb 12] Stagecoach connections were available from there to Anstruther and St Andrews.[64]

On 18 September 1832 the exiled and bankrupt French King Charles X used the pier to leave Scotland for Hamburg.[54] On 4 June 1833 the ferry Benlomond caught fire just after leaving the pier for Stirling. The Lion and the Stirling Castle rescued all 220 passengers from the ferry before it sank in shallow water west of the pier, 40 minutes after departure.[65]

In 1834 a clock and a large bell were placed at the entrance to the pier. The bell was rung just before each steamer's departure time in order to prevent delays.[66] That year there were ferries from Trinity to Stirling, Alloa, Charlestown, Aberdour, Dysart, Leven, and Largo.[67] In 1835 a journey to Dundee cost 5 shillings, or 3/- for steerage.[nb 13] The Rothesay left the Chain Pier at 6:30 am and returned from Dundee at 2 pm each day during the summer.[68] Other destinations by 1842 included Crombie Point, Bo'ness and Limekilns.[6] The Stirling Castle made a pleasure trip to the Bass Rock and the Isle of May from the pier in 1832.[69] In 1836 the steam packet from the Chain Pier to Dundee was advertised as carrying mail, including parcels and light goods.[70]

Early in its life, Alexander Nasmyth, who was a keen amateur engineer, depicted the pier in a watercolour painting; the work, "The Old Chain Pier, Newhaven", belongs to the Scottish National Gallery.[nb 14] In 2002 it featured in an exhibition along with the contemporary Edinburgh paintings of Turner.[71] A calotype of the pier taken in 1840 was among a collection of 206 early photographs of Edinburgh discovered in an auction in Swindon in 2002. The National Library of Scotland bought them for over £200,000[nb 15] and placed the images online.[72]

In 1835 the total number of passengers using Newhaven harbour and the Chain Pier was estimated at 400,000 per year,[73] but the number of ferries using the pier began to decline as Leith and Newhaven improved their harbour facilities. In 1834 there had been rival plans to build a large new harbour, either at Trinity or Granton.[74] The latter was chosen and in 1838 the first phase of the Duke of Buccleuch's new harbour opened at Granton,[75] causing Chain Pier traffic to fall even further.[76]

Sea bathing

In the early 19th century, a fashion for sea bathing had gripped Britain. The activity was pursued for pleasure and the health benefits it was thought to confer.[77] The Alloa Steam Packet Company bought the pier in 1840,[78] and they leased it to John Greig, who installed changing cubicles. Male bathers paid one penny to use the pier.[76] By 1842 the pier was mainly used by bathers.[79]

In the 1840s the development of the railway network made travel vastly quicker and more accessible.[80][nb 16] From 1842 the Edinburgh, Leith and Newhaven Railway provided access to the pier for ferry passengers and bathers,[73] initially with horse-drawn trains running from Scotland Street in Canonmills to Trinity railway station, the original northern terminus of the line. In 1845 a reduced fare crossing on the Royal Tar was advertised; steerage from Trinity to Leven or Largo was now 1/2,[nb 17] and connecting trains from Scotland Street were available.[82] The line was well-used[83] and the rail company replaced Trinity station with a new one in 1846 when they extended the line to the new harbour at Granton.[nb 18] The Edinburgh and Northern Railway opened a railway across Fife in 1847,[85] absorbed the Edinburgh, Leith and Newhaven Railway in 1848,[86] and started the world's first train ferry from Granton to Burntisland in 1850.[7][nb 19][nb 20][nb 21]

In June 1847 Captain John Bush, of the Kirkcaldy and London Shipping Company, married Margaret Greig, daughter of a shipmaster, at the pier.[90] In 1849 a lifebuoy and rope were provided at the pier head for swimmers who got into difficulty.[91] A ladder leading into the sea was provided for swimmers, in addition to the stairs which were for use by steamboat passengers.[92] By the 1850s the pier was falling into disrepair,[93] but it was still popular with bathers, and early-morning trains were advertised allowing for a swim before work.[91][94] There was a gymnasium at the head of the pier,[95] and the Forth Swimming Club was based there from its inception in 1850.[96] They organised swimming competitions, including "fast swimming" and "long diving" which were, respectively, a 300-yard (270 m) race and an underwater endurance contest.[97] "Deep diving" involved retrieving objects from the bottom in 20 feet (6.1 m) of water[98] then surfacing through a floating lifebuoy.[99] A longer race was from Newhaven harbour to the Chain Pier, a distance of 550 yards (500 m). In 1864 the winning time was 11 minutes and 35 seconds.[100] Two floating platforms were moored east of the pier;[101] the closer one was about 20–25 yards (18–23 m) out.[102] In July 1858 an attempt was made to restart ferry services from the pier; this caused annoyance to swimmers.[103]

In 1859 the Colonial Life Assurance Company acquired the pier,[20] and from about 1860 the Eckford family leased the pier from them. The owners employed a caretaker, but the pier became dilapidated, and required expensive repairs to keep open.[104] In June 1860 when the Royal Navy's Channel Fleet was visiting Queensferry, there were three trips a day from the pier to see the fleet.[105] In November 1861 the Commissioners of Leith Docks challenged the operation of the pier in a case at the Court of Session, as they argued that the right to build and operate the pier was not transferable from the London, Leith, Edinburgh and Glasgow Steam Navigation Company to the subsequent owners and operators.[20] In February 1862 it was offered for sale, with the suggestion that it could be re-installed elsewhere as either a pier or a bridge.[106] Some locals were concerned that the pier's opening on Sundays for swimming would distract people from going to church; the availability of beer was also noted.[107] By 1869, as well as the train service, there were regular omnibuses from the Mound to the Chain Pier and also to the Trinity Baths, a nearby sea bath[108] which had opened prior to 1829.[109] Hot and cold sea water were available by the pitcher there.[110] On 26 July 1879, 3,000 spectators lined the shore to see the Scottish Swimming Championship, which took place between the Chain Pier and Granton breakwater. It was won by Wilson of Glasgow with a time of 17 minutes. All the competitors used an overhand stroke.[111] The popularity of sea bathing declined as the water became increasingly polluted with sewage and industrial waste, and the focus of bathing moved to indoor pools.[112] Sea bathing continued at Portobello beach, 3.4 miles (5.5 km) east of the city centre.[97][113][nb 22]

From 1 March 1864 until 31 August 1865, Captain Thomas measured sea temperatures from the Chain Pier. The data supported the acceptance of the Gulf Stream as a mechanism to explain the warmer seas around Scotland, especially in the west.[115] In 1869, as an experiment into using electric light for lighthouses, Thomas Stevenson had an underwater cable installed from the eastern breakwater of Granton harbour. An operator on the harbour wall, with a switch and a Bunsen cell (an early form of battery), controlled a light on the end of the Chain Pier from half a mile (800 m) away.[116][117][118]

There were many drownings[nb 23] and rescues[nb 24] from the pier over the years, and from early on a focus of the swimming clubs was life-saving.[130] In 1871 the Royal Humane Society awarded James Crichton a badge and sash for saving two lives in a week, the second from the Chain Pier.[131] In 1880 the Lorne Swimming Club awarded a silver medal to T Shepherd for saving the life of a trumpeter from Leith Fort,[132] and in 1882 the Forth Swimming Club and Humane Society awarded a certificate to James H Walls for saving two swimmers from the pier that July.[133] In 1889 ladies' swimming lessons were advertised, as well as gymnastics, massage and "medical electricity".[134] In 1890 the Forth Bridge at Queensferry enabled direct rail travel from Edinburgh to Fife; 20,000 trains had crossed it by 1910.[135][nb 25]

The pier was badly damaged on 18 October 1898 by a storm which lasted four days and caused great destruction all over Scotland. Several steam and sailing vessels were sunk or driven ashore and wrecked in the vicinity of the pier.[138] The storm completely removed the deck and chains, destroyed the platform closest to shore, and damaged the remaining two platforms (the pier head and the second support platform).[139] The pier was never repaired and its ruin was eroded away by the sea. Some remnants of the wooden piles that supported the pier can still be seen at low tide.[95]

Old Chain Pier

The public house at the shore end was known as the Pier Bar in 1878.[140] It was badly damaged in a fire in March 1898, which caused over £600[nb 26] worth of damage.[141] It survived the pier's destruction later that year,[142] and became known as the Old Chain Pier. It was run by Arthur Moss, whose name appeared on the building into the 1970s.[143] In June 1956 the ladies' toilet was added.[144] In the 1960s the landlady, Betty Moss, was known for encouraging customers to leave at closing time by waving a cutlass or a gun.[145] In 1979 permission was granted for an extension of the pub.[146] The pub was fitted with a 60-centimetre (24 in) higher roof in 1983; it was owned by Drybrough's brewery by then.[144] A conservatory was added in 1998.[143] CAMRA selected it (jointly with the Guildford Arms) as Edinburgh's pub of the year in 2001.[147][148]

The Old Chain Pier was rebuilt after a major fire in 2004.[149] It is the only building on the north side of Trinity Crescent, and part of the pub juts out over the sea. In 2007 the City of Edinburgh Council forced it to take down large awnings it had installed without planning permission following the smoking ban the previous year.[150][151] The pub was described during the process as "a twentieth century reconstruction of the original building". It is within the Trinity Conservation Area.[152] It was refurbished in 2011, and now operates as a pub and restaurant.[143] Its beers are Timothy Taylor Brewery's Landlord bitter, and a selection from Alechemy.[153] The restaurant specialises in seafood.[154] It has a gluten-free menu and children are welcome in the conservatory and mezzanine.[155]

References

Notes

- In Brown's 1822 account he refers to it as Trinity Pier of Suspension,[1] The common name Chain Pier appears in sources as early as 1827.[2] Modern sources tend to call it Trinity Chain Pier.

- Geologically a glacial valley or fjord; firth is cognate with fjord.

- In the 20th century, following the ascendancy of motorised road transport, the M90 motorway and the Forth Road Bridge (1964) were built.[3] The construction of the Queensferry Crossing (expected to open in 2016[4]) underlines the continuing importance of this transport axis.[5]

- An 1828 account describes the journey from Edinburgh to Glasgow via the Chain Pier and Grangemouth, then by the Forth and Clyde, as taking more than thirteen hours, when a stagecoach could do it in four and a half, for half the cost.[12]

- The first commercially successful steamboat in Europe, Henry Bell's Comet of 1812,[13] triggered a rapid expansion of steam services on the Clyde,[14] and by 1840 there were fifty-seven Clyde steamers.[15]

- Equivalent to £349,000 in 2015 values, when adjusted for historic opportunity cost.[25]

- The bolts were 2 inches (50.8 mm) in diameter at the suspension points, 1 7⁄8 inches (47.6 mm) further out and 1 3⁄4 inches (44.5 mm) at the centres of the spans.[33]

- Brown called them "piers".[33]

- Part of this survives inside the modern pub, and is marked with a plaque.

- £18,359 in modern purchasing power.[50]

- Anderson (1763–1861) had earlier made an unsuccessful proposal to build a suspension bridge across the firth at Queensferry.[61]

- Equivalent to £9.15.[50]

- Equivalent to £24.8 and £14.88 respectively.[50]

- In the National Gallery, the date for the painting is given as 1819. This may be a cataloguing error; many of the dates were supplied by the artist's son after his death.

- £383,451 at 2015 prices.[50]

- 1,200 miles (1,900 km) of track were laid down in Scotland in the space of a few years.[81]

- Equivalent to £5.81.[50]

- In 1847 they opened a new city-centre terminus at Canal Street, on the site of the modern Edinburgh Waverley station. It involved a steep gradient through a tunnel, which was operated by rope-hauled trains.[8] Robert Louis Stevenson wrote about "The tunnel to the Scotland Street Station, the sight of the two guards upon the brake..."[84]

- The pioneering slipway was designed by Thomas Bouch (1822–1880) whose first Tay Bridge (1878) collapsed in a storm in December 1879 killing everyone on board a train that was crossing it.[87] He was personally blamed for the disaster and died soon after.[88]

- A second train ferry from Tayport to Broughty Ferry allowed through services from Edinburgh to Dundee and Aberdeen.[85]

- Passenger services to Trinity ceased in 1925, and the line is now a footpath. The former station survives as a private house.[89]

- Seafield Baths opened in 1813 as Leith's first indoor bathing facility.[97] Portobello Pier opened in 1871. It was designed by Thomas Bouch, was 1,250 feet (380 m) long, and was demolished in 1917.[114] Leith's first indoor swimming pool was the Victoria Baths in 1896.[97]

- Some examples:[91][119][120][121][122][123][124][125]

- Some examples:[79][126][127][128][129]

- About 60,000 trains cross the bridge every year in the early 21st century.[136] The Granton-Burntisland ferry service survived until the Second World War, and an attempt was made to revive it using a catamaran in 1991–93.[7] In 2007 Stagecoach trialled a hovercraft service from Portobello to Kirkcaldy.[137]

- £67,000 in modern purchasing power.[50]

Citations

- Brown (1822), p. 22.

- "Kinghorn Ferry". The Scotsman. 22 August 1827. p. 535.

- Charlesworth (1984), p. 177.

- "Queensferry Crossing becomes UK's tallest bridge". BBC Online. 13 August 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "FRC FAQs". Transport Scotland. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. 7. A. and C. Black. 1842. p. 768.

- Meighan (2014).

- Smith & Anderson (1995), p. 20.

- Scott (1819), p. 19.

- Foyster & Whatley (2010), p. 261.

- Griffiths & Morton (2010), p. 149.

- "Rough Notes On a Ride to the North". Dublin Evening Packet and Correspondent. 11 September 1828. p. 4.

- Derry & Williams (1960), p. 328.

- Clark (2007), p. 162.

- Freeman (1991), p. 265-266.

- Griffiths & Morton (2010), p. 148-149.

- Drewry (1832), p. 42.

- Curious (1833), p. 24.

- Brown (1822), p. 23.

- "Law Intelligence". Caledonian Mercury. 23 November 1861. p. 3.

- Kawada (2010), p. 30.

- Scotland. Court of Session (1836). Cases Decided in the Court of Session. Bell & Bradfute. p. 925.

- Erredge (1862), p. 314.

- The Topographical, Statistical, and Historical Gazetteer of Scotland: I-Z. A. Fullarton. 1842. p. 400.

- "Measuring Worth". Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- Marshall (2010), p. 20.

- Skempton (2002), p. 86.

- Drewry (1832), p. 37.

- Brown (1822), p. 26.

- Brown (1822), p. 27.

- Marshall (2010), p. 27.

- Drewry (1832), p. 69.

- Brown (1822), p. 24.

- "Suspension-Bridges in Modern Times". The Saturday Magazine. John William Parker. 7: 212. 1836.

- "Steam Betwixt Dundee and Edinburgh Every Lawful Day, In Five Hours!". Perthshire Courier. 3 May 1838. p. 1.

- Drewry (1832), p. 43–44.

- Skempton (2002), p. 87.

- Kawada (2010), p. 29.

- Brown (1822), p. 25.

- Drewry (1832), p. 45.

- Drewry (1832), p. 43.

- Stark (1834), p. 315.

- "Volumes 87–88". The Scots Magazine. Sands, Brymer, Murray and Cochran: 481. 1821.

- Kranakis (1997), p. 151.

- Wallace (1997), p. 103.

- "Opening of the Suspension Pier at Trinity". The Scotsman. 25 August 1821. p. 271.

- "Suspension Pier at Newhaven". Caledonian Mercury. 16 August 1821. p. 3.

- "Harbours in the Firth of Forth". The Scotsman. 26 April 1837. p. 2.

- "Summary". The Scotsman. 14 February 1835. p. 2.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Chain Pier at Trinity". Caledonian Mercury. 27 April 1822. p. 3.

- "No title". The Scotsman. 3 September 1823. p. 566.

- Hutton (1995), p. 53.

- Wallace (1984), p. 27.

- "Anstruther Harbour". Dundee Courier. 23 November 1904. p. 4.

- Session, Scotland. Court of (1822). Cases Decided in the Court of Session. Bell & Bradfute. pp. 219–220. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Front Page". The Scotsman. 15 April 1826. p. 233.

- "Correspondence". The Scotsman. 29 August 1829. p. 559.

- Buckland (2008), p. 188.

- Brewster (1828), p. 157–158.

- Skempton (2002), p. 15.

- Topping (1990), p. 52.

- "Shameful Deception! Caution to the Public". Fife Herald. 12 August 1830. p. 1.

- "Advertisement". Fife Herald. 14 April 1831. p. 1.

- "Destruction of the Benlomond Steampacket". The Scotsman. 5 June 1833. p. 3.

- "Chain Pier". The Scotsman. 19 July 1834. p. 3.

- Pollock's new guide through Edinburgh. Pollock & Co. 1834. p. 181.

- "Classified advert". The Scotsman. 28 February 1835. p. 3.

- "Pleasure excursion to the Island of May". The Scotsman. 27 June 1832. p. 3.

- "Daily Conveyance to Edinburgh, at the Reduced Fares". Perthshire Advertiser. 30 June 1836. p. 1.

- "Art lovers get a look behind the scenes". Edinburgh Evening News. 11 January 2002. p. 24. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- "Haunting images of city back in the light". The Scotsman. 19 November 2002. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- "City of Edinburgh Railway". The Scotsman. 28 November 1835. p. 4.

- "Mr. Cubitt's Report on Leith Harbour and Docks, &c". The Scotsman. 8 October 1834. p. 4.

- "Granton History: Granton Harbour Handbook 1937 (text)". 1937. Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- Wallace (1997), p. 104.

- Feltham (1813), p. iii.

- Grant (1880), p. 303.

- "Heroic Conduct – Gentleman saved from Drowning". The Scotsman. 27 August 1842. p. 2.

- Griffiths & Morton (2010), p. 151.

- Marwick (1964), p. 87.

- "Important Reduction of Fares". Northern Warder and General Advertiser for the Counties of Fife, Perth and Forfar. 12 June 1845. p. 1.

- "Edinburgh, Leith and Granton Railway". The Scotsman. 15 February 1845. p. 3.

- Stevenson (2015), p. 194.

- "Edinburgh and Northern Railway". Railscot. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- "The Railway Chronicle: Joint-stock Companies Journal. Register of Traffic". J. Francis. 1848: 347. Retrieved 6 September 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Tay Bridge Disaster: Report Of The Court of Inquiry" (PDF). Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- Lewis, Peter; Reynolds, Ken (2002). "Forensic engineering: a reappraisal of the Tay Bridge disaster" (PDF). Milton Keynes: Open University. p. 296. Retrieved 12 September 2015.

- "Edinburgh, Leith and Newhaven Railway". RAILSCOT. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- "Married". Caledonian Mercury. 24 June 1847. p. 3.

- "Melancholy Accident". The Scotsman. 11 July 1849. p. 3.

- "To the Editor of the Caledonian Mercury". Caledonian Mercury. 19 April 1849. p. 3.

- "Lost Edinburgh: Portobello Pier". The Scotsman. 31 March 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- Wallace (1997), p. 104-105.

- "Granton History: The Chain Pier". Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "The Old Chain Pier At Trinity". Edinburgh Evening News. 13 September 1920. p. 4.

- Marshall (1985), p. 62.

- "Forth Swimming Club". The Scotsman. 23 July 1859. p. 2.

- "Forth Swimming Club and Humane Society". Edinburgh Evening News. 24 July 1873. p. 2.

- "Forth Swimming Club – Long Distance Match". The Scotsman. 26 August 1864. p. 2.

- "The Chain Pier". The Scotsman. 23 September 1865. p. 7.

- "Forth Swimming Club". The Scotsman. 26 July 1864. p. 2.

- "Bathing at the Chain Pier". Edinburgh Evening Courant. 10 July 1858. p. 2.

- "Forth Swimming Club". The Scotsman. 25 July 1860. p. 2.

- "Channel Fleet". Caledonian Mercury. 12 June 1860. p. 1.

- "For Sale, For the Purpose of Removal, the Chain Pier at Trinity near Edinburgh". Edinburgh Evening Courant. 18 February 1862. p. 1.

- "Trinity Chain Pier on Sunday". Edinburgh Evening Courant. 29 June 1866. p. 6.

- "Trinity Baths and Chain Pier". Edinburgh Evening Courant. 4 August 1869. p. 2.

- "Eligible bathing quarters". Edinburgh Evening Courant. 11 June 1829. p. 1.

- "Trinity Baths". Edinburgh Evening Courant. 15 September 1857. p. 1.

- "The Scottish Swimming Championship". Edinburgh Evening News. 28 July 1879. p. 2.

- Wallace (1997), p. 105.

- Wallace (1984), p. 26.

- "Portobello Promenade pier designs revealed". Edinburgh Evening News. 3 June 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Petermann, von Freeden & Mühry (1871), p. 244–246.

- Stevenson (2009), p. 165–166.

- "The Nautical Magazine and Naval Chronicle for 1869". Cambridge Library Collection. 28 March 2013: 614–615. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Scientific Items". Montreal Witness. 7 July 1871. p. 4. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "Two Persons Drowned at Trinity". Edinburgh Evening News. 7 February 1878. p. 2.

- "Sad Case of Drowning at Trinity". Edinburgh Evening News. 29 August 1878. p. 2.

- "Man Drowned at Trinity". Edinburgh Evening News. 27 May 1880. p. 2.

- "Edinburgh Gentleman Drowned at Trinity". Edinburgh Evening News. 25 December 1888. p. 3.

- "Leith Labourer Drowned at Newhaven". Edinburgh Evening News. 17 October 1904. p. 2.

- "No title". The Scotsman. 28 July 1824. p. 567.

- "Fatal Boating Accident at Newhaven". Edinburgh Evening News. 15 July 1892. p. 2.

- "Bathing Accident". Caledonian Mercury. 18 September 1843. p. 3.

- "Narrow Escape and Gallant Rescue". Caledonian Mercury. 10 August 1861. p. 2.

- "Narrow Escape From Drowning". Edinburgh Evening News. 29 June 1885. p. 2.

- "Attempted Suicide at Trinity Chain Pier". Edinburgh Evening News. 24 April 1895. p. 4.

- "Forth Swimming Club and Humane Society". The Scotsman. 31 August 1865. p. 2.

- Fevyer & Barclay (2013), p. 77.

- "Lorne Swimming Club Soiree". Edinburgh Evening News. 11 December 1880. p. 2.

- "Forth Swimming Club and Humane Society". Edinburgh Evening News. 18 November 1882. p. 2.

- "Classified advertisement". The Scotsman. 6 August 1889. p. 1.

- Jennings (2004), p. 289.

- "Forth Rail Bridge, Firth of Forth – Railway Technology". Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Veitch (2009), p. 290.

- Hutton (1995), p. 84-85.

- "The Great Gale: Extraordinary Destruction of Property". The Scotsman. 19 October 1898. p. 9.

- "Classified advertisements". Edinburgh Evening News. 18 July 1878. p. 1.

- "Fire at Trinity Chain Pier". Edinburgh Evening News. 7 March 1898. p. 2.

- Hutton (1995), p. 84.

- "Granton History: The Old Chain Pier Bar". Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "Historic planning records". The City of Edinburgh Council. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- Le Vay (2004), p. 70.

- "Applications for planning permission and/or listed building consent" (PDF). The Gazette. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "Real ale fans aficionados vote Guildford and Chain Pier top in city". Edinburgh Evening News. 23 December 2000. p. 14.

- "History and charm at The Old Chain Pier". The Scotsman. 10 March 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- "Fire guts historic city pub". Edinburgh Evening News. 29 April 2004. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- "Chain smokers likely to lose shelters at under-fire pub". The Scotsman. 19 February 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- "Time called on seafront pub's smoke shelters". Edinburgh Evening News. 23 February 2007. p. 11.

- Development Quality Sub-committee of the Planning Committee. "Advert Application 061045771ADV at 32 Trinity Crescent Edinburgh EH5 3ED". City of Edinburgh Council.

- "Old Chain Pier, Edinburgh Pub Details". whatpub.com. 6 March 2015. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- Johnstone, Lindsey (20 March 2015). "The most beautiful places to eat in Edinburgh". The Scotsman. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- "Old Chain Pier (32 Trinity Crescent, Newhaven, Edinburgh)". The List. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

Bibliography

- Brewster, Sir David (1828). The Edinburgh Journal of Science. 8. William Blackwood.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, Samuel (1822). The Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal: Exhibiting a View of the Progressive Discoveries and Improvements in the Sciences and the Arts. 6. Adam and Charles Black.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buckland, Francis T. (2008) [First published between 1857 and 1872]. Curiosities of Natural History. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-6052-0552-6. Retrieved 3 October 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Charlesworth, George (1984). A History of British Motorways. T. Telford. ISBN 978-0-7277-0159-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clark, Basil (2007). Steamboat Evolution. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-8475-3201-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curious, Peter (1833). A Peep into Leith Harbour, or the Works of the Town Council of Edinburgh. Effingham Wilson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Derry, Thomas Kingston; Williams, Trevor Illtyd (1960). A Short History of Technology from the Earliest Times to A.D. 1900, Part 1900. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-4862-7472-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drewry, Charles Stewart (1832). A Memoir on Suspension Bridges, Comprising the History of Their Origin and Progress, and of Their Application to Civil and Military Purposes. Longmans, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, & Longman.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Erredge, John Ackerson (1862). History of Brighthelmston, or Brighton as I view it and others knew it. Oxford University.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Feltham, John (1813). A guide to all the watering and sea-bathing places; with a description of the lakes; a sketch of a tour in Wales; and itineraries, by the editor of The picture of London. Retrieved 18 September 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fevyer, W.H.; Barclay, Craig P. (18 February 2013). Acts of Gallantry. 3. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-1-7815-0317-1. Retrieved 16 September 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Foyster, Elizabeth A.; Whatley, Christopher A., eds. (2010). A History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1600 to 1800. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1965-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Freeman, Michael J (1991). Transport in Victorian Britain. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-2333-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grant, James (1880). Old and New Edinburgh. 6. Cassell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Griffiths, Trevor; Morton, Graeme, eds. (2010). History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1800 to 1900. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2169-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutton, Guthrie (1995). Old Leith. Ochiltree, Ayrshire: Stenlake. ISBN 978-1-8720-7465-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jennings, Alan (2004). Structures: From Theory to Practice. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-4152-6842-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kawada, Tadaki (30 April 2010). History of the Modern Suspension Bridge: Solving the Dilemma between Economy and Stiffness. American Society of Civil Engineers. ISBN 978-0-7844-1018-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kranakis, Eda (10 January 1997). Constructing a Bridge: Exploration of Engineering Culture, Design and Research in Nineteenth-century France and America. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-2621-1217-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Le Vay, Benedict (2004). Eccentric Edinburgh. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-8416-2098-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marshall, James Scott (25 October 1985). The Life and Times of Leith. John Donald Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0-8597-6128-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marshall, John (2010) [First published between 1823 and 1830]. Royal Naval Biography: Or, Memoirs of the Services of All the Flag-Officers, Superannuated Rear-Admirals, Retired-Captains, Post-Captains, and Commanders. 4. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-1080-2271-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marwick, W. H. (1964). Scotland in Modern Times: An Outline of Economic and Social Development. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7146-1342-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meighan, Michael (30 August 2014). The Forth Bridges Through Time. ISBN 978-1-4456-4010-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petermann, August; von Freeden, Wilhelm; Mühry, Adolf (1871). Papers on the Eastern and Northern Extensions of the Gulf Stream. U.S. Government Printing Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scott, Walter (1819). The Antiquary. Archibald Constable and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skempton, A. W. (2002). A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland: 1500–1830. Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-7277-2939-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, W. A. C.; Anderson, Paul (1995). An Illustrated History of Edinburgh's Railways. Caernarfon: Irwell Press. ISBN 978-1-8716-0859-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stark, John (1834). Picture of Edinburgh: Containing a Description of the City and Its Environs. Edinburgh: J. Anderson.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stevenson, Robert Louis (10 April 2015) [First published 1879]. Collected Memoirs, Travel Sketches and Island Literature of Robert Louis Stevenson. e-artnow. ISBN 978-8-0268-3395-6. Retrieved 18 September 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stevenson, Thomas (9 April 2009) [First published 1881]. Lighthouse Construction and Illumination. BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-1039-0095-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Topping, B.H.V., ed. (31 December 1990). Developments in Structural Engineering: Proceedings of the Forth Rail Bridge Centenary Conference. 1. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-4191-5240-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Veitch, Kenneth, ed. (2009). Transport and Communications. John Donald. ISBN 978-1-9046-0788-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallace, Joyce M. (26 October 1984). Traditions of Trinity and Leith. John Donald Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0-8597-6447-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallace, Joyce M. (26 September 1997). Further Traditions of Trinity and Leith. John Donald Publishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0-8597-6282-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)