Peter Behrens

Peter Behrens (14 April 1868 – 27 February 1940) was a leading German architect and industrial designer, best known for his early pioneering AEG Turbine Hall in Berlin in 1909. He had a long career, designing objects, typefaces, and important buildings in a range of styles from the 1900s to the 1930s. He was a foundation member of the German Werkbund in 1907, when he also began designing for AEG, pioneered corporate design, producing typefaces, objects, and buildings for the company. In the next few years, he became a successful architect, a leader of the rationalist / classical German Reform Movement of the 1910s. After WW1 he turned to Brick Expressionism, designing the remarkable Hoechst Administration Building outside Frankfurt, and from the mid 1920s increasingly to New Objectivity. He was also an educator, heading the architecture school at Academy of Fine Arts Vienna from 1922-1936. As a well known architect he produced design across Germany, in other European countries, Russia and England. Several of the leading names of European modernism worked for him when they were starting out in the 1910s, including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius.

Peter Behrens | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Peter Behrens by Max Liebermann | |

| Born | 14 April 1868 |

| Died | 27 February 1940 (aged 71) Berlin, Prussian Free State, Nazi Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Buildings | AEG Turbine Factory |

| Projects | Deutscher Werkbund |

Biography

Behrens attended the Christianeum Hamburg from September 1877 until Easter 1882. He studied painting in his native Hamburg, as well as in Düsseldorf and Karlsruhe, from 1886 to 1889. In 1890, he married Lilly Kramer and moved to Munich. At first, he worked as a painter, illustrator and bookbinder in an artisanal fashion. He frequented the bohemian circles and was interested in subjects related to the reform of lifestyles. In 1899 Behrens accepted the invitation of the Grand Duke Ernst-Ludwig of Hesse to be the second member of his recently inaugurated Darmstadt Artists' Colony, where Behrens built his own Jugendstil style house in 1901, and fully conceived everything, from furniture to towels, paintings, pottery, etc. The building of this house is considered to be the turning point in his life, when he left the artistic circles of Munich and showed himself to be a talented architect in his very first project.

In 1903, Behrens was named director of the Kunstgewerbeschule in Düsseldorf, where he implemented successful reforms, developing new ways of teaching design.[1] In 1907, Behrens and ten other people (Hermann Muthesius, Theodor Fischer, Josef Hoffmann, Joseph Maria Olbrich, Bruno Paul, Richard Riemerschmid, Fritz Schumacher, among others), plus twelve companies, gathered to create the German Werkbund. As an organization, it was clearly indebted to the principles and priorities of the Arts and Crafts movement, but tending towards the classical in architecture. Members of the Werkbund were focused on improving the overall level of taste in Germany by improving the design of everyday objects and products. This very practical aspect made it an extremely influential organization among industrialists, public policy experts, designers, investors, critics and academics. His work in the early 1900s included a series of exhibition halls and pavilions, a crematorium and some private houses, which show a new direction immediately after his own Jugendstil house, towards exploring simple, rectilinear volumes and classical sources.[2]

In 1907, AEG (Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft) retained Behrens as artistic consultant, and his work for AEG was the first large-scale demonstration of the viability and vitality of the Werkbund's initiatives and objectives. He designed the entire corporate identity (logotype, product design, publicity, etc.) and for that he is considered the first industrial designer in history. He also designed a series of factory buildings for them at their two Berlin factory sites, most famously the 1909 AEG Turbine Factory, at the Moabit site, considered an early example of Modernism. He then went on to design four new buildings at the Humboldthain site, which showed that he was as much interested in massive, bold, classical and picturesque effects depending on the context, as expressing modernity. Since Peter Behrens was a consultant rather than an employee of AEG, he was free to work on other projects, and developed a highly successful architectural practice. In this period his growing office had many students and assistants, some who would go on become leading Modernists, including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe,[3] Le Corbusier, Adolf Meyer, Jean Kramer and Walter Gropius (later to become the first director of the Bauhaus).

Immediately after the AEG Turbine Hall, he designed a series of large office buildings in a bold monumental stripped classical form, part of the German Reform Architecture movement. His 1912 German Embassy in St Petersburg, and the Administration Building for Continental AG in Hannover, built 1912-1914 are good examples of this period.

After WW1 his work changed again, and like many German architects, he explored the themes and styles of Brick Expressionism. Between 1920 and 1924, he was responsible for the design and construction of the Technical Administration Building of Hoechst AG in Höchst, outside Frankfurt. With its soaring atrium clad in coloured bricks representing the factory’s dye products, and an exterior in dark clinker bricks with clocktower and dramatic arch, it is one of the most representative examples of the style in Germany.

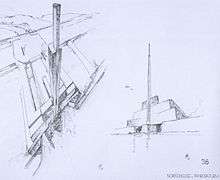

In 1922, he accepted an invitation to teach at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, becoming head of the architecture school, a post he kept until 1936, whilst also designing for a range of clients across Europe. In 1926, Behrens was commissioned by the Englishman Wenman Joseph Bassett-Lowke to design a family home in Northampton, UK. The house named 'New Ways', a stark white walled rectangular volume (with jagged parapets), is often regarded as probably the first modernist house in Britain,[4] and marks Behrens' turn towards the Modernism of New Objectivity.

In 1925 he was invited by his former student Mies van der Rohe, along with many of the leading German architects working in the new style, to design a residential building in Stuttgart, in the development now known as the Weissenhof. His contribution was a set of apartments in stacked cubic volumes, allowing many apartments to open to large terraces.

In 1928 Behrens won an international competition for the construction of the New Synagogue, in Zilnia, Czechia, which was restored in 2012-17 as a cultural centre.[5] The same year he designed a renovation of the Feller-Stern department store in central Zagreb, Croatia, transforming it from Art Nouveau to a complex almost De Stijl Modernist composition. His 1931 hillside villa for the Clara Gans, daughter of Frankfurt industrialist Adolf Gans, was a similarly complex interplay of rectangular volumes, clad in stone, a fine example of New Objectivity.

In 1929, Behrens was invited to the competition for the design of buildings around a proposed radical redesign of Alexanderplatz in Berlin, and though he came second, his designs for the buildings on the south west side of the new square was preferred by the subsequent developer,[6] and the Alexanderhaus and the Berolinahaus were built by 1932.

In 1929, Behrens, in partnership with former student Alexander Popp, was commissioned to design a new factory for the state-run Austria Tabak in Linz, which was built over a long period, due to the economic conditions, finally completed in 1935. The main building has a very long completely horizontal slightly curved facade, Behrens’ most striking design in the style of New Objectivity.

In 1936 Behrens left Vienna to teach architecture at the Prussian Academy of Arts (now the Akademie der Künste) in Berlin, reportedly with the specific approval of Hitler. Behrens participated in Hitler's plans for the rebuilding of Berlin with the commission for the new headquarters of the AEG on Albert Speer's famous planned north–south axis. Speer reported that his selection of Behrens for this commission was rejected by the powerful Alfred Rosenberg, but that his decision was supported by Hitler who admired Behrens's Saint Petersburg Embassy. Behrens died in the Hotel Bristol in Berlin on 27 February 1940, while seeking refuge there from the cold of his country estate.[1]

List of projects

German Embassy St Petersburg, 19121900–1901: Behrens house on Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt

German Embassy St Petersburg, 19121900–1901: Behrens house on Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt 'Weissenhof' apartment building, Stuttgart, 1927

'Weissenhof' apartment building, Stuttgart, 1927- 1905–1907: Villa Obenauer in Saarbrücken

- 1905–1908: Eduard Müller Crematorium in Hagen-Delstern

- 1906: Interior design of the state and city library in the extension of the Kunstgewerbemuseum Düsseldorf

- 1908–1909: AEG Turbine hall, Berlin-Moabit

- 1908–1909: Schröder house in Hagen (destroyed in World War II)

- 1909–1910: Catholic Fellowship House in Neuss

- 1909-1910: Villa Cuno in Hagen

- 1909-10: High Voltage Factory, AEG, Berlin - Humboldthain

- 1910: Boathouse "Elektra" for the Berlin rowing company "Elektra" in Berlin-Oberschöneweide, founded in 1908 as a rowing club for employees and civil servants of the AEG

- 1910: Exhibition hall (temporary wooden structure, named Hetzerhalle) for the German Railways with a span of 43 meters for the Brussels World Exhibition in 1910, built by the entrepreneur Otto Hetzer from Weimar

- 1911: Gasworks Ost in Frankfurt am Main, Osthafen

- 1911: AEG factory settlement in Hennigsdorf

- 1911–1912: Mannesmann House in Düsseldorf

- 1911–1912: German Embassy in Saint Petersburg

- 1911–1912: House for government architect C. H. Goedecke in Hagen

- 1911–1912: Wiegand house, home for the archaeologist and museum director Theodor Wiegand in Berlin-Dahlem, today the seat of the German Archaeological Institute

- 1912: AEG Large Motors Factory, Berlin - Humboldthain

- 1912–1914: Administration building of Continental AG in Hanover (extension 1919–1920), today the House of Economic Development

- 1913: AEG Small Motors Factory, Berlin - Humboldthain

- 1914: Frank & Lehmann office building in Cologne, 37 Unter Sachsenhausen

Alexanderhaus and Berolinahaus, Alexanderplatz, 1932

Alexanderhaus and Berolinahaus, Alexanderplatz, 1932 - 1914–1917: Factory for the National Automobile Society (NAG) in Berlin-Oberschöneweide (later the factory for television electronics , called Peter-Behrens-Bau)

- 1915: Wuhlheide forest settlement in Berlin-Karlshorst, Hegemeisterweg

- 1918: Oberschöneweide settlement in Berlin (built 1919-21 to plans by others, Behrens only designed some single family houses[7])

- 1919: Workers' and master craftsmen's settlement for Deutsche Werft AG in Hamburg-Finkenwerder[8]

- 1921–1925: Technical administration building of Hoechst AG in Frankfurt-Höchst

- 1921–1925: Administration building of the Gutehoffnungshütte in Oberhausen

- 1925: Tomb for Friedrich Ebert in Heidelberg, in the mountain cemetery

- 1925-1926: College of St. Benedict in Salzburg

- 1926:'New Ways', Northampton, UK

- 1927: Apartment house in the Weißenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart (lots 31 + 32)

Tabacco Factory, Linz, 1929-35

Tabacco Factory, Linz, 1929-35 - 1928: Reconstruction of Feller-Stern department store, Ban Jelačić Square in Zagreb, Croatia

- 1928–1929: U-Bahn stations, line U 8 in Berlin (Moritzplatz, Bernauer Straße, Voltastraße, designed 1912)

- 1928-1930: Franz-Domes-Hof in Vienna - Margareten

- 1929: Residence for Kurt Lewin in Berlin- Nikolassee , Waldsängerpfad 3

- 1929–1930: Group of apartment buildings in Berlin- Westend , Bolivarallee 9

- 1929-1931: Villa Gans in Kronberg im Taunus, Falkensteiner Straße 19, Hesse

- 1929-1931: Synagogue in Žilina , Kuzmányho 1

- 1929-1935: Tobacco factory in Linz (with Alexander Popp)

- 1930–1932: Alexanderhaus and Berolinahaus at Alexanderplatz in Berlin

- 1931: “Ring der Frauen” house at the German Building Exhibition in 1931 in Berlin-Charlottenburg (demolished)

- 1932–1933: Hohenlanke house near Neustrelitz (planned as a separate retirement home, partially completed)

- 1933–1951: Christ the King Curch in Linz (with Alexander Popp , Hans Feichtlbauer and Hans Foschum)

Typefaces designed by Behrens

All faces cast by the Klingspor Type Foundry.

- Behrens-Schrift (1901-7)

- Behrens-Antiqua (1907-9)

- Behrens Mediaeval (1914)

Gallery

Behrens house, Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt, 1901

Behrens house, Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt, 1901- Eduard Müller Krematorium, Hagen-Delstern, 1908

- High Tension Factory, AEG, Berlin-Moabit, 1909-10

Large Motors Factory, AEG Berlin-Humbolthain, 1912

Large Motors Factory, AEG Berlin-Humbolthain, 1912 German Embassy, St Petersberg, 1912

German Embassy, St Petersberg, 1912 Mannesmann Haus, Duesseldorf, 1912

Mannesmann Haus, Duesseldorf, 1912 Office Building, Unter Sachsenhause 37, Cologne, 1914

Office Building, Unter Sachsenhause 37, Cologne, 1914 Continental AG offices, Hannover, 1912-14

Continental AG offices, Hannover, 1912-14 National Automobile Society (NAG), Berlin, 1914-17

National Automobile Society (NAG), Berlin, 1914-17 Hoechst Administration Building, Frankfurt, 1921-24

Hoechst Administration Building, Frankfurt, 1921-24 Hoechst Administration, Frankfurt, 1921-25

Hoechst Administration, Frankfurt, 1921-25 Gutehoffnungshütte warehouse, Oberhausen, 1921-25

Gutehoffnungshütte warehouse, Oberhausen, 1921-25 Tomb of Friedrich Ebert, 1925

Tomb of Friedrich Ebert, 1925 College of St. Benedict, Salzburg, 1926

College of St. Benedict, Salzburg, 1926 Feller-Stern department store, Ban Jelačić Square, Zagreb,1928

Feller-Stern department store, Ban Jelačić Square, Zagreb,1928 Franz Domes Hof, Vienna, 1928-30

Franz Domes Hof, Vienna, 1928-30.jpg) Villa Gans, Kronberg, 1931

Villa Gans, Kronberg, 1931- Synagogue, Žilina, Slovakia, 1929-31

.jpg) Alexanderhaus and Berolinhaus, Alexanderplatz, Berlin, 1930-32

Alexanderhaus and Berolinhaus, Alexanderplatz, Berlin, 1930-32 Tabacco Factory, Linz, Austria, 1929-35

Tabacco Factory, Linz, Austria, 1929-35 Tobacco Factory, Linz, 1929-35

Tobacco Factory, Linz, 1929-35

References

- Anderson, Stanford (2000). Peter Behrens and a New Architecture for the Twentieth Century. The MIT Press. p. 252. ISBN 0-262-01176-X.

- Anderson, Stanford (1980). "Peter Behrens and Industrial Design" (PDF). Oppositions – via http://web.mit.edu.

- Anderson, Stanford (2010). "Considering Peter Behrens Interviews with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe" (PDF). engremmar – via http://web.mit.edu/.

- Historic England. "New Ways, Northampton (Grade II*) (1052387)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 Jun 2018.

- Borský (2007), 160.

- "engramma - la tradizione classica nella memoria occidentale n.172". www.engramma.it. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Liste, Karte, Datenbank / Landesdenkmalamt Berlin". www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de. Retrieved 2020-05-16.

- "Beamtensiedlung der Deutschen Werft". hamburg.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-05-16.

- Sources

- Borský, Maroš (2007). Synagogue Architecture in Slovakia: Towards Creating a Memorial Landscape of Lost Community. PhD dissertation, Hochschule für Jüdische Studien, Heidelberg. Accessed 23 November 2014.

- A. Windsor (1981): Peter Behrens: Architect and Designer, Humanities Press Intl; First US edition, ISBN 0-85139-072-2

- Stanford Anderson (2002): Peter Behrens and a New Architecture for the Twentieth Century, The MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-51130-4 ISBN 978-0262511308

- Peter Behrens (1990): Peter Behrens: Umbautes, Licht Prestel Pub, ISBN 3-7913-1059-3 (German edition)

- Kathleen James-Chakraborty (2000): German architecture for a mass audience, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-23654-1

- Ina Bahnschulte-Friebe: Künstlerkolonie Mathildenhöhe Darmstadt 1899–1914. Darmstadt: Institut Mathildenhöhe 1999, ISBN 3-9804553-6-X (in German)

- Georg Krawietz: "Peter Behrens im dritten Reich", Weimar 1995, VDG, Verlag und Datenbank für Geisteswissenschaften, ISBN 3-929742-57-8 (in German)

- Klaus J. Sembach: 1910 – Halbzeit der Moderne. Stuttgart: Hatje 1992, ISBN 3-7757-0392-6 (in German)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peter Behrens. |

- Virtual gallery with Behrens designs for AEG

- The synagogue of Zilina, Slovakia designed by Peter Behrens

- Neolog Synagogue in Žilina Attached plaque: “This synagogue was built by the world famous architect Peter Behrens, in 1933–1934, on the same site as the original synagogue built in 1881. It served as a place of Jewish worship until the arrival of facism. World War II tragically affected the lives of the Slovak Jews, at the time 3,600 Jewish people helped make up the 19,000 population of Žilina. After the war, only 500 Jewish survivers returned. Since the end of war, the building has been used for cultural and educational purposes by the city and as a technical college. Jewish congregation of Žilina 1934–1996.”

- The Schiedmayer grand piano from the musicroom of the House Behrens 1901

- Newspaper clippings about Peter Behrens in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW