Transport in Niger

Transport in Niger is composed of the transportation systems and methods used in this landlocked nation, with cities separated by huge uninhabited deserts, mountain ranges, and other natural features. A poor nation, Niger's transport system was little developed during the colonial period (1899–1960), relying upon animal transport, human transport, and limited river transport in the far south west and south east. No railways were constructed in the colonial period, and roads outside the capital remained unpaved. The Niger River is unsuitable for large-scale river transport, as it lacks depth for most of the year and is broken by rapids at many spots. Camel caravan transport was historically important in the Sahara desert and Sahel regions which cover most of the north.

Governance

Transport, including motor vehicles, highways, airports, and port authorities, are overseen by the Nigerien Ministry of Transport's Directorate for Land Water and Air Transport ("Ministère des Transport et de l'aviation civile/Direction des Transports Terrestres, Maritimes et Fluviaux"). Border controls and import/export duties are overseen by an independent tax police, the "Police du Douanes. Air traffic control is overseen and operated in conjunction with the pan-African ASECNA, which bases one of its five air traffic zones at Niamey's Hamani Diori International Airport.[1] A non-governmental body, the Nigerien Council of Users of Public Transport ("Conseil Nigérien des Utilisateurs des Transports Publics CNUT") advocates on behalf of users of public transport, including roads and airports.[2]

Highways

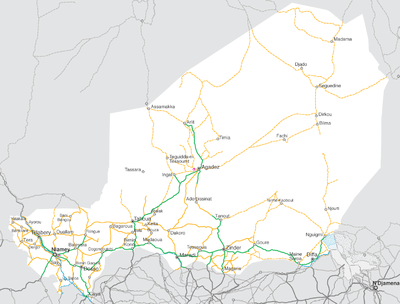

Outside of cities, the first major paved roads were constructed from the northern town of Arlit to the Benin border in the 1970s and 1980s. This road, dubbed the Uranium Highway,[3] runs through Arlit, Agadez, Tahoua, Birnin-Konni, and Niamey, and is part of the Trans-Sahara Highway system.

An additional paved highway runs from Niamey via Maradi and Zinder towards Diffa in the far east of the nation, although the stretch from Zinder to Diffa is only partially paved. Portions of this route are used by the Trans-Sahel Highway route. The Niger section is 837 km long (of which 600 km was in poor condition as of 2000), via Niamey, Dosso, Dogondoutchi, Birnin-Konni and Maradi to the Nigerian border at Jibiya.

Other roads range from all-weather laterite surfaces to grated dirt or sand Pistes, especially in the arid north.

The United States government in 1996 estimated there were a total of 10100 km of highways in Niger, with 798 km paved and 9302 km, unpaved, but making no distinction between improved or all weather roads and unimproved roads.[4] In 2012, there is 19,675 kilometres (12,225 mi) of road network throughout Niger, of which only 4,225 kilometres (2,625 mi) are paved.[5]

Routes Nationale

The national road system ("Routes Nationale") are numbered and prefixed with "RN", as RN1. The numbering system contains routes or sections which are as yet unpaved or even unimproved tracks. Route Nationale no. 25, for example, is a major paved highway from Niamey to Filingué, follows the partially improved Route Nationale no. 26 towards Abala, veers off onto a dirt track (locally called a Piste) from the villages of Talcho to Sanam, where RN26 also terminates from another direction. RN25 then continues along a piste through largely uninhabited desert for almost 100 km before reaching the city of Tahoua, served by other major paved roads. The main "Uranium Highway" then coincides with the RN25 all the way to Arlit in the far north. Consequently, the informal names for the routes (e.g. "Uranium Highway") serves a somewhat more practical purpose than the RN numbers.[6][7][8]

Road transport

Nigeriens in both urban and rural areas rely on a combination of motor vehicles and animals for transport of themselves and commercial goods. Road transport is the major form of travel across the huge distances between Nigerien population centers, though most Nigeriens do not own vehicles. In cities, public transport systems are largely absent, so a variety of privately operated services carry many urban dwellers. Vans, cars, motor coaches, trucks, and even converted motorbikes provide paid transport. Intercity coach systems are the standard form of personal transport, with the government operating one bus service (the SNTV), and a multitude of buses, "bush taxis" (taxi brousse), small vans and semi-converted trucks taking passengers and goods. Services are sometimes scheduled from the "Highway stations" ("Gares routières") found in every town, but are more frequently ad hoc: vehicles ply the trade between towns, picking up at stations or anywhere along the route, and departing only when full.[6]

Animals pulling wagons and loaded camel trains remain a common sight on Nigerien roads.[6]

Motor vehicle regulation

Vehicles in Niger are subject to the "Laws of the Road" ("Code de la route") for which the government began a continuing reform in 2004-2006 and is based substantially on French models.[9] Vehicles travel on the right side of the road, and roads use French style signage.[6] Routes Nationale are marked with the traditional French Milestones: a white tablet with a red top, marked with the route number. Vehicles owners must obtain a Registration document ("Carte grise") and Vehicle license plates ("plaques d’immatriculation"), which are of similar manufacture to those in Guinea and Mali.[10] Licence plates usually contain the national code "RN" for international travel.[11] Niger is a signatory of the September 1949 Geneva Convention on Road Traffic, and thus honours International drivers licenses from other signatories.[12] Drivers licenses are regulated through the national Ministry of Transport, but issued by local officials.[13] Drivers must pass a drivers test to qualify.[14]

A 2009 enforcement blitz in Niamey resulted in numerous arrests of owners of small motorbikes, common in Nigerien cities. One newspaper reported that most riders believed erroneously that there was no license or regulation required by law for motorbikes under 50cc in engine size, although these had been regulated in law since 2002 but not enforced.[15] Motorbikes are also common means of public transport in some Nigerien cities. These motorcycle "taxis motos", or "kabu kabu", are the primary form of taxis in cities like Zinder, Agadez, and Maradi. In Zinder, a 2009 local newspaper report claimed there were no more than "three to five" automobile taxis operating in a diffuse city which subsequently relies upon the only partially regulated motorcycle taxi sector.[16]

Road safety

Road accidents have been identified as a major public health concern by the Nigerien government. According to Chékarou Bagoudou, Chief of the Division of Road Safety and Security of the Nigerien Ministry of Transport, there were 4338 officially reported road accidents in 2008, with 7443 victims, of which 616 were killed. With the Nigerien government counting 18949 km of roads in the nation, this comes to one accident for every five kilometers in 2008. Speaking before a National Assembly session, Bagoudou said that the 42.2 billion CFA francs spent on medical costs for road accident victims accounted for around 25% of the 2008 budget of the Nigerien Ministry of Public Health. Transport figures concluded that 70% of road accidents were caused by "human factors", 23% by mechanical faults and 7% by road conditions.[17]

Waterways

The Niger River is navigable 300 km from Niamey to Gaya on the Benin frontier from mid-December to March. Thereafter a series of falls and rapids render the Niger unnavigable in all seasons. In the navigable stretches, shallows prevent all but the small draft African canoes (Pirogues and Pinnases) from operating in many areas. As there is only one major bridge over the Niger (The Kennedy Bridge in Niamey: the Niger River bridge at Gaya crosses into Benin), car ferries are of crucial importance, especially the crossing at Bac Farie, 40 km north of Niamey on the RN4, and the car ferry at Ayorou.[6]

Despite having no ocean or deep draft river ports, Niger does operate a ports authority. Niger relies on the port at Cotonou (Benin), and to a lesser degree Lomé (Togo), and Port Harcourt (Nigeria), as its main route to overseas trade. Abidjan was in the process of regaining Niger's port trade, following the disruption of the Ivorian Civil War, beginning in 1999.[18] Niger operates a Nigerien Ports Authority station, as well as customs and tax offices in a section of Cotonou's port, so that imports and exports can be directly transported between Gaya and the port. French Uranium mines in Arlit, which produce Niger's largest exports by value, travel through this port to France or the world market.

Airports

The US government estimated there were 27 airports and/or landing strips in Niger as of 2007.[4] Nine (9) of these had paved runways, 18 with unpaved landing strips. ICAO Codes for Niger are prefixed "DR".

Of the 9 Airports with paved runways, 2 with paved strips from 2,438 to 3,047 m: Diori Hamani International Airport and Mano Dayak International Airport. These are the only two Nigerien airports with regular international commercial flights. Six of the remainder have strips between 1,524 and 2,437 m, while one is under 914 m. 18 additional airports have unpaved runways 15 of them with strips between 914 and 1,523 m.

Major airports (with ICAO code and IATA code) include:[19]

- DRRM (MFQ) – Maradi Airport – Maradi

- DRRN (NIM) – Diori Hamani International Airport – Niamey

- DRRT (THZ) – Tahoua Airport – Tahoua

- DRZA (AJY) – Mano Dayak International Airport – Agadez South

- DRZL (RLT) – Arlit Airport – Arlit

- DRZR (ZND) – Zinder Airport – Zinder

- DRZF () – Diffa Airport – Diffa

- DRZD () – Dirkou Airport – Dirkou

- DRRB (BKN) – Birni N'Konni Airport – Birni N'Konni

Other airstrips (with ICAO codes) include:[20]

Railway

Niger is a user of the Benin and Togo railway lines which carry goods from seaports to the Niger border. Rail lines to Niamey and other points in Niger were proposed during the colonial period, and continue to be discussed. In 2012, a multi-national railway system was proposed to connect Benin, Niger, Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast.[21]

Other lines connecting Nigeria to Niger have also been discussed. For example, on August 13, 2013 in Nigeria, the Vice President of Nigeria Namadi Sambo announced that Nigeria is to construct a line into the Republic of Niger. The new track will be an extension the existing branch from Zaria to Kaura-Namoda, which is to be continued via Sokoto to Birnin Kebbi. In the longer term it will extend the line across the border to Niamey, capital of Niger. The existing branch is currently out of commission, but rehabilitation has commenced.

In April 2014, Niamey Railway Station[22][23] was officially inaugurated and construction began for the railway extension connecting Niamey to Cotonou via Parakou (Benin).[24][25] This railway line is expected to go through Dosso city and Gaya in the territory of Niger before crossing into Benin. The line Niamey–Dosso city is expected to be completed before December 2014.

See also

References

- ASECNA

- Visites du ministre des Transports et de l'Aviation Civile à l'aéroport international Diori Hamani de Niamey et au CNUT : s'enquérir des conditions de travail des agents Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Seini Seydou Zakaria, le Sahel (Niamey) 18 June 2009

- Tertrais, Bruno (2014). "Uranium from Niger:: A key resource of diminishing importance for France". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - CIA World Factbook: Niger. updated on 20 November 2008

- Annuaire statistique du Niger - Transport routier. Institute of Statistics of Niger - Road Transport Report. 2008-1012.

- Geels, Jolijn (2006). Niger. Chalfont St Peter, Bucks / Guilford, Connecticut: Bradt UK / Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 978-1-84162-152-4.

- Michelin Afrique Nord et Ouest 741 (Map). 1:4000000. Michelin Publications. 2007. ISBN 978-2-06-712832-3.:100–200, 235

- IGN Carte Touristique 85029 Niger(1) (Map). 1:2000000. IGN(Paris)/IGNN(Niamey). 1994. ISBN 978-2-11-850291-1.

- Solicitation de manifestation d'interet: Services de consultants: "Services de consultants pour l’actualisation du code de la route: recrutement d’un consultant individuel international, expert en sécurité routière". REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER, MINISTERE DES TRANSPORTS ET DE L’AVIATION CIVILE, DIRECTION DES TRANSPORTS TERRESTRES, MARITIMES ET FLUVIAUX. 2 March 2009

- Cartes grises et plaques d’immatriculation : “Le Système Holocis” contre la fraude Archived 9 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Le Republicain (Bamako). 16 September 2008

- FRANCOPLAQUE: a gallery of Nigerien license plates, current and historic.

- Drivers license Archived 24 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine. International University of Japan.

- Permis de conduire Archived 25 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine: French Embassy to Niger. Retrieved 13 May 2009

- Vers une réforme de l'examen du permis de conduire au Niger. Niamey, Niger (PANA). 18 March 2002

- CONTRÔLE DES PLAQUES D’IMMATRICULATION DES MOTOS 50 CM3 Plus de 300 motos saisies en une semaine Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Le Republicain (Niamey). 12 May 2009.

- Les taxis motos ou kabu kabu incorrigibles?. Les Echos (Zinder). 3 March 2009, p. 2.

- Journée parlementaire à l'Assemblée nationale : la question de la sécurité routière en débat à l'hémicycle Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Zabeirou Moussa. Le Sahel, Niamey. 8 May 2009.

- Abidjan port regains its regional importance African Business, Oct, 2008 by Marcel Gossio.

- Airports of Niger, World Aero Data/ Aviation Networks, Inc.

- Airports Niger. PictAero.com / Association de Gestion d'AeroWeb-fr.

- Article on railwaysafrica.com

- (in French) "Inauguration of the first train station in Niamey" (Radio France Internationale)

- "A 80 Year-long Wait: Niger Gets its First Train Station" (Global Voices Online)

- Article on railpage.com.au

- Article on news.xinhuanet.com

- Jolijn Geels. Niger. Bradt UK/ Globe Pequot Press USA (2006) ISBN 978-1-84162-152-4

- Samuel Decalo. Historical Dictionary of Niger (3rd ed.). Scarecrow Press, Boston & Folkestone, (1997) ISBN 0-8108-3136-8

- Abdou Bontianti et Issa Abdou Yonlihinza, La RN 6 : un exemple d’intégration économique sous-régionale et un facteur de désenclavement du Niger, Les Cahiers d’Outre-Mer, 241-242 January–June 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

External links

![]()