Mesoamerican ballgame

The Mesoamerican ballgame was a sport with ritual associations played since at least 1650 BCE[1] by the pre-Columbian people of Ancient Mesoamerica. The sport had different versions in different places during the millennia, and a newer more modern version of the game, ulama, is still played by the indigenous populations in some places.[2]

The rules of the game are not known, but judging from its descendant, ulama, they were probably similar to racquetball,[3] where the aim is to keep the ball in play. The stone ballcourt goals are a late addition to the game.

In the most common theory of the game, the players struck the ball with their hips, although some versions allowed the use of forearms, rackets, bats, or handstones. The ball was made of solid rubber and weighed as much as 4 kg (9 lbs), and sizes differed greatly over time or according to the version played.

The game had important ritual aspects, and major formal ballgames were held as ritual events. Late in the history of the game, some cultures occasionally seem to have combined competitions with religious human sacrifice. The sport was also played casually for recreation by children and may have been played by women as well.[4]

Pre-Columbian ballcourts have been found throughout Mesoamerica, as for example at Copán, as far south as modern Nicaragua, and possibly as far north as what is now the U.S. state of Arizona.[5] These ballcourts vary considerably in size, but all have long narrow alleys with slanted side-walls against which the balls could bounce.

Names

The Mesoamerican ballgame is known by a wide variety of names. In English, it is often called pok-ta-pok (or pok-a-tok). This term originates from a 1932 article by Danish archaeologist Frans Blom, who adapted it from the Yucatec Maya word pokolpok.[6][7] In Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, it was called ōllamaliztli ([oːlːamaˈlistɬi]) or tlachtli ([ˈtɬatʃtɬi]). In Classical Maya, it was known as pitz. In modern Spanish, it is called juego de pelota maya ('Mayan ballgame'),[8] juego de pelota mesoamericano ('Mesoamerican ballgame'),[9] or simply pelota maya ('Mayan ball').

Origins

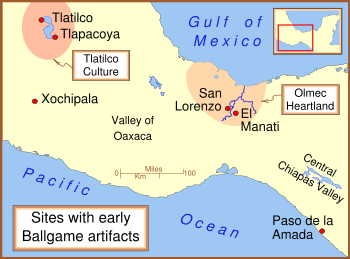

It is not known precisely when or where ōllamaliztli originated, although it is likely that the game originated earlier than 1400 BCE in the low-lying tropical zones home to the rubber tree.[10]

One candidate for the birthplace of the ballgame is the Soconusco coastal lowlands along the Pacific Ocean.[11] Here, at Paso de la Amada, archaeologists have found the oldest ballcourt yet discovered, dated to approximately 1400 BCE.[12]

The other major candidate is the Olmec heartland, across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec along the Gulf Coast.[13] The Aztecs referred to their Postclassic contemporaries who then inhabited the region as the Olmeca (i.e. "rubber people") since the region was strongly identified with latex production.[14] The earliest-known rubber balls in the world come from the sacrificial bog at El Manatí, an early Olmec-associated site located in the hinterland of the Coatzacoalcos River drainage system. Villagers, and subsequently archaeologists, have recovered a dozen balls ranging in diameter from 10 to 22 cm from the freshwater spring there. Five of these balls have been dated to the earliest-known occupational phase for the site, approximately 1700–1600 BCE.[15] These rubber balls were found with other ritual offerings buried at the site, indicating that even at this early date ōllamaliztli had religious and ritual connotations.[16][17] A stone "yoke" of the type frequently associated with Mesoamerican ballcourts was also reported to have been found by local villagers at the site, leaving open the distinct possibility that these rubber balls were related to the ritual ballgame, and not simply an independent form of sacrificial offering.[18][19]

Excavations at the nearby Olmec site of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán have also uncovered a number of ballplayer figurines, radiocarbon-dated as far back as 1250–1150 BCE. A rudimentary ballcourt, dated to a later occupation at San Lorenzo, 600–400 BCE, has also been identified.[20]

From the tropical lowlands, ōllamaliztli apparently moved into central Mexico. Starting around 1000 BCE or earlier, ballplayer figurines were interred with burials at Tlatilco and similarly styled figurines from the same period have been found at the nearby Tlapacoya site.[21] It was about this period, as well, that the so-called Xochipala-style ballplayer figurines were crafted in Guerrero. Although no ballcourts of similar age have been found in Tlatilco or Tlapacoya, it is possible that the ballgame was indeed played in these areas, but on courts with perishable boundaries or temporary court markers.[22]

By 300 BCE, evidence for ōllamaliztli appears throughout much of the Mesoamerican archaeological record, including ballcourts in the Central Chiapas Valley (the next oldest ballcourts discovered, after Paso de la Amada),[23] and in the Oaxaca Valley, as well as ceramic ballgame tableaus from Western Mexico (see photo below).

Material and formal aspects

As might be expected with a game played over such a long period of time by many cultures, details varied over time and place, so the Mesoamerican ballgame might be more accurately seen as a family of related games.

In general, the hip-ball version is most popularly thought of as the Mesoamerican ballgame,[24] and researchers believe that this version was the primary—or perhaps only—version played within the masonry ballcourt.[25] Ample archaeological evidence exists for games where the ball was struck by a wooden stick (e.g., a mural at Teotihuacan shows a game which resembles field hockey), racquets, bats and batons, handstones, and the forearm, perhaps at times in combination. Each of the various types of games had its own size of ball, specialized gear and playing field, and rules.

Games were played between two teams of players. The number of players per team could vary, between two to four.[26][27] Some games were played on makeshift courts for simple recreation while others were formal spectacles on huge stone ballcourts leading to human sacrifice.

Even without human sacrifice, the game could be brutal and there were often serious injuries inflicted by the solid, heavy ball. Today's hip-ulama players are "perpetually bruised"[28] while nearly 500 years ago Spanish chronicler Diego Durán reported that some bruises were so severe that they had to be lanced open. He also reported that players were even killed when the ball "hit them in the mouth or the stomach or the intestines".[29]

The rules of ōllamaliztli, regardless of the version, are not known in any detail. In modern-day ulama, the game resembles a netless volleyball,[30] with each team confined to one half of the court. In the most widespread version of ulama, the ball is hit back and forth using only the hips until one team fails to return it or the ball leaves the court.

In the Postclassic period, the Maya began placing vertical stone rings on each side of the court, the object being to pass the ball through one, an innovation that continued into the later Toltec and Aztec cultures.

In the 16th-century Aztec ballgame that the Spaniards witnessed, points were lost by a player who let the ball bounce more than twice before returning it to the other team, who let the ball go outside the boundaries of the court, or who tried and failed to pass the ball through one of the stone rings placed on each wall along the center line.[31] According to 16th-century Aztec chronicler Motolinia, points were gained if the ball hit the opposite end wall, while the decisive victory was reserved for the team that put the ball through a ring.[32] However, placing the ball through the ring was a rare event—the rings at Chichen Itza, for example, were set six meters off the playing field—and most games were likely won on points.[33]

Clothing and gear

_2.jpg)

The game's paraphernalia—clothing, headdresses, gloves, all but the stone—are long gone, so knowledge on clothing relies on art—paintings and drawings, stone reliefs, and figurines—to provide evidence for pre-Columbian ballplayer clothing and gear, which varied considerably in type and quantity. Capes and masks, for example, are shown on several Dainzú reliefs, while Teotihuacan murals show men playing stick-ball in skirts.[34]

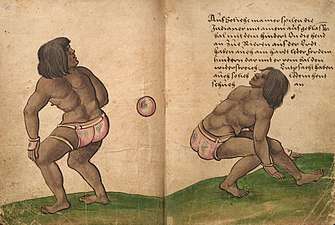

The basic hip-game outfit consisted of a loincloth, sometimes augmented with leather hip guards. Loincloths are found on the earliest ballplayer figurines from Tlatilco, Tlapacoya, and the Olmec culture, are seen in the Weiditz drawing from 1528 (below), and, with hip guards, are the sole outfit of modern-day ulama players (above)—a span of nearly 3,000 years.

In many cultures, further protection was provided by a thick girdle, most likely of wicker or wood covered in fabric or leather. Made of perishable materials, none of these girdles have survived, although many stone "yokes" have been uncovered. Misnamed by earlier archaeologists due to its resemblance to an animal yoke, the stone yoke is thought to be too heavy for actual play and was likely used only before or after the game in ritual contexts.[35] In addition to providing some protection from the ball, the girdle or yoke would also have helped propel the ball with more force than the hip alone. Additionally, some players wore chest protectors called palmas which were inserted into the yoke and stood upright in front of the chest.

Kneepads are seen on a variety of players from many areas and eras and are worn by forearm-ulama players today. A type of garter is also often seen, worn just below the knee or around the ankle—it is not known what function this served. Gloves appear on the purported ballplayer reliefs of Dainzú, roughly 500 BCE, as well as the Aztec players are drawn by Weiditz 2,000 years later (see drawing below).[36][29] Helmets (likely utilitarian) and elaborate headdresses (likely used only in ritual contexts) are also common in ballplayer depictions, headdresses being particularly prevalent on Maya painted vases or on Jaina Island figurines. Many ballplayers of the Classic era are seen with a right kneepad—no left—and a wrapped right forearm, as shown in the Maya image above.

Rubber balls

The sizes or weights of the balls actually used in the ballgame are not known with any certainty. While several dozen ancient balls have been recovered, they were originally laid down as offerings in a sacrificial bog or spring, and there is no evidence that any of these were used in the ballgame. In fact, some of these extant votive balls were created specifically as offerings.[37]

However, based on a review of modern-day game balls, ancient rubber balls, and other archaeological evidence, it is presumed by most researchers that the ancient hip-ball was made of a mix from one or another of the latex-producing plants found all the way from the southeastern rain forests to the northern desert.[38] Most balls were made from latex sap of the lowland Castilla elastica tree. Someone discovered that by mixing latex with sap from the vine of a species of morning glory (Calonyction aculeatum) they could turn the slippery polymers in raw latex into a resilient rubber. The size varied between 10 and 12 in (25 and 30 cm) (measured in hand spans) and weighed 3 to 6 lb (1.4 to 2.7 kg).[39] The ball used in the ancient handball or stick-ball game was probably slightly larger and heavier than a modern-day baseball.[40][41]

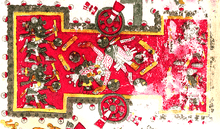

Some Maya depictions, such as the painting above or this relief, show balls 1 m (3 ft 3 in) or more in diameter. Academic consensus is that these depictions are exaggerations or symbolic, as are, for example, the impossibly unwieldy headdresses worn in the same portrayals.[42][43]

Ballcourt

Ōllamaliztli was played within a large masonry structure. Built in a form that changed remarkably little during 2,700 years, over 1,300 Mesoamerican ballcourts have been identified, 60% in the last 20 years alone.[44] Although there is a tremendous variation in size, in general all ballcourts have the same shape: a long narrow playing alley flanked by walls with both horizontal and sloping (or, more rarely, vertical) surfaces. The walls were often plastered and brightly painted. Although the alleys in early ballcourts were open-ended, later ballcourts had enclosed end-zones, giving the structure an ![]()

Across Mesoamerica, ballcourts were built and used for many generations. Although ballcourts are found within most sizable Mesoamerican ruins, they are not equally distributed across time or geography. For example, the Late Classic site of El Tajín, the largest city of the ballgame-obsessed Classic Veracruz culture, has at least 18 ballcourts, while Cantona, a nearby contemporaneous site, sets the record with 24.[47] In contrast, northern Chiapas[48] and the northern Maya Lowlands[49] have relatively few, and ballcourts are conspicuously absent at some major sites, including Teotihuacan, Bonampak, and Tortuguero, although ōllamaliztli iconography has been found there.[50]

Ancient cities with particularly fine ballcourts in good condition include Tikal, Yaxha, Copán, Coba, Iximche, Monte Albán, Uxmal, Chichen Itza, Yagul, Xochicalco, Mixco Viejo, and Zaculeu.

Ballcourts were public spaces used for a variety of elite cultural events and ritual activities like musical performances and festivals, and, of course, the ballgame. Pictorial depictions often show musicians playing at ballgames, while votive deposits buried at the Main Ballcourt at Tenochtitlan contained miniature whistles, ocarinas, and drums. A pre-Columbian ceramic from western Mexico shows what appears to be a wrestling match taking place on a ballcourt.[51]

Cultural aspects

Proxy for warfare

Ōllamaliztli was a ritual deeply ingrained in Mesoamerican cultures and served purposes beyond that of a mere sporting event. Fray Juan de Torquemada, a 16th-century Spanish missionary and historian, tells that the Aztec emperor Axayacatl played Xihuitlemoc, the leader of Xochimilco, wagering his annual income against several Xochimilco chinampas.[52] Ixtlilxochitl, a contemporary of Torquemada, relates that Topiltzin, the Toltec king, played against three rivals, with the winner ruling over the losers.[53]

These examples and others are cited by many researchers who have made compelling arguments that ōllamaliztli served as a way to defuse or resolve conflicts without genuine warfare, to settle disputes through a ballgame instead of a battle.[54][55] Over time, then, the ballgame's role would expand to include not only external mediation, but also the resolution of competition and conflict within the society as well.[56]

This "boundary maintenance" or "conflict resolution" theory would also account for some of the irregular distribution of ballcourts. Overall, there appears to be a negative correlation between the degree of political centralization and the number of ballcourts at a site.[53] For example, the Aztec Empire, with a strong centralized state and few external rivals, had relatively few ballcourts while Middle Classic Cantona, with 24 ballcourts, had many diverse cultures residing there under a relatively weak state.[57][58]

Other scholars support these arguments by pointing to the warfare imagery often found at ballcourts:

- The southeast panel of the South Ballcourt at El Tajín shows the protagonist ballplayer being dressed in a warrior's garb.[59]

- Captives are a prominent part of ballgame iconography. For example:

- The modern-day descendant of the ballgame, ulama, "until quite recently was connected with warfare and many reminders of that association remain".[60]

Human sacrifice

The association between human sacrifice and the ballgame appears rather late in the archaeological record, no earlier than the Classic era.[61][62] The association was particularly strong within the Classic Veracruz and the Maya cultures, where the most explicit depictions of human sacrifice can be seen on the ballcourt panels—for example at El Tajín (850–1100 CE)[63] and at Chichen Itza (900–1200 CE)—as well as on the decapitated ballplayer stelae from the Classic Veracruz site of Aparicio (700–900 CE). The Postclassic Maya religious and quasi-historical narrative, the Popol Vuh, also links human sacrifice with the ballgame (see below).

Captives were often shown in Maya art, and it is assumed that these captives were sacrificed after losing a rigged ritual ballgame.[64] Rather than nearly nude and sometimes battered captives, however, the ballcourts at El Tajín and Chichen Itza show the sacrifice of practiced ballplayers, perhaps the captain of a team.[65][66] Decapitation is particularly associated with the ballgame—severed heads are featured in much Late Classic ballgame art and appear repeatedly in the Popol Vuh. There has been speculation that the heads and skulls were used as balls.[67]

Symbolism

Little is known about the game's symbolic contents. Several themes recur in scholarly writing.

- Astronomy. The bouncing ball is thought to have represented the sun.[68] The stone scoring rings are speculated to signify sunrise and sunset, or equinoxes.

- War. This is the most obvious symbolic aspect of the game (see also above, "Proxy for warfare"). Among the Mayas, the ball can represent the vanquished enemy, both in the late-Postclassic K'iche' kingdom (Popol Vuh), and in Classic kingdoms such as that of Yaxchilan.

- Fertility. Formative period ballplayer figurines—most likely females—often wear maize icons.[69] At El Tajín, the ballplayer sacrifice ensures the renewal of pulque, an alcoholic maguey cactus beverage.

- Cosmologic duality. The game is seen as a struggle between day and night,[65] and/or a battle between life and the underworld.[70] Courts were considered portals to the underworld and were built in key locations within the central ceremonial precincts. Playing ball engaged one in the maintenance of the cosmic order of the universe and the ritual regeneration of life.

Myth

Nahua

According to an important Nahua source, the Leyenda de los Soles,[71] the Toltec king Huemac played ball against the Tlalocs, with precious stones and quetzal feathers at stake. Huemac won the game. When instead of precious stones and feathers, the rain deities offered Huemac their young maize ears and maize leaves, Huemac refused. As a consequence of this vanity, the Toltecs suffered a four-year drought. The same ball game match, with its unfortunate aftermath, signified the beginning of the end of the Toltec reign.

Maya

The Maya Twin myth of the Popol Vuh establishes the importance of the game (referred to in Classic Maya as pitz) as a symbol for warfare intimately connected to the themes of fertility and death. The story begins with the Hero Twins' father, Hun Hunahpu, and uncle, Vucub Hunahpu, playing ball near the underworld, Xibalba.[72] The lords of the underworld became annoyed with the noise from the ball playing and so the primary lords of Xibalba, One Death and Seven Death, sent owls to lure the brothers to the ballcourt of Xibalba, situated on the western edge of the underworld. Despite the danger the brothers fall asleep and are captured and sacrificed by the lords of Xibalba and then buried in the ballcourt. Hun Hunahpu is decapitated and his head hung in a fruit tree, which bears the first calabash gourds. Hun Hunahpu's head spits into the hands of a passing goddess who conceives and bears the Hero Twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque. The Hero Twins eventually find the ballgame equipment in their father’s house and start playing, again to the annoyance of the Lords of Xibalba, who summon the twins to play the ballgame amidst trials and dangers. In one notable episode, Hunahpu is decapitated by bats. His brother uses a squash as Hunahpu's substitute head until his real one, now used as a ball by the Lords, can be retrieved and placed back on Hunahpu's shoulders. The twins eventually go on to play the ballgame with the Lords of Xibalba, defeating them. However, the twins are unsuccessful in reviving their father, so they leave him buried in the ball court of Xibalba.

The ballgame in Mesoamerican civilizations

Maya civilization

In Maya Ballgame the Hero Twins myth links ballcourts with death and its overcoming. The ballcourt becomes a place of transition, a liminal stage between life and death. The ballcourt markers along the centerline of the Classic playing field depicted ritual and mythical scenes of the ballgame, often bordered by a quatrefoil that marked a portal into another world. The Twins themselves, however, are usually absent from Classic ballgame scenes, with the Classic forerunner of Vucub Caquix of the Copán ball court, holding the severed arm of Hunahpu, as an important exception.[73]

Teotihuacan

No ballcourt has yet been identified at Teotihuacan, making it by far the largest Classic era site without one. In fact, the ballgame seems to have been nearly forsaken not only in Teotihuacan, but in areas such as Matacapan or Tikal that were under Teotihuacano influence.[74]

Despite the lack of a ballcourt, ball games were not unknown there. The murals of the Tepantitla compound at Teotihuacan show a number of small scenes that seem to portray various types of ball games, including:

- A two-player game in an open-ended masonry ballcourt.[75] (See third picture below.)

- Teams using sticks on an open field whose end zones are marked by stone monuments.[75]

- Separate renditions of single players. (See side pictures above.)

It has been hypothesized that, for reasons as yet unknown, the stick-game eclipsed the hip-ball game at Teotihuacan and at Teotihuacan-influenced cities, and only after the fall of Teotihuacan did the hip-game reassert itself.[76]

Ballplayer painting from the Tepantitla murals.

Ballplayer painting from the Tepantitla murals..jpg) Ballplayer painting from the Tepantitla, Teotihuacan murals. Note the speech scroll issuing from the player's mouth.

Ballplayer painting from the Tepantitla, Teotihuacan murals. Note the speech scroll issuing from the player's mouth. Detail of a Tepantitla mural showing a hip-ball game on an open-ended ballcourt, represented by the parallel horizontal lines.

Detail of a Tepantitla mural showing a hip-ball game on an open-ended ballcourt, represented by the parallel horizontal lines.

Aztec

The Aztec version of the ballgame is called ōllamalitzli (sometimes spelled ullamaliztli)[77] and are derived from the word ōlli "rubber" and the verb ōllama or "to play ball". The ball itself was called ōllamaloni and the ballcourt was called a tlachtli [ˈtɬatʃtɬi].[78] In the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan the largest ballcourt was called Teotlachco ("in the holy ballcourt")—here several important rituals would take place on the festivals of the month Panquetzalitzli, including the sacrifice of four war captives to the honor of Huitzilopochtli and his herald PaInal.

For the Aztecs the playing of the ballgame also had religious significance, but where the 16th-century K´iche´ Maya saw the game as a battle between the lords of the underworld and their earthly adversaries, their Aztec contemporaries may have seen it as a battle of the sun, personified by Huitzilopochtli, against the forces of night, led by the moon and the stars, and represented by the goddess Coyolxauhqui and Coatlicue's sons the 400 Huitznahuah.[79] But apart from holding important ritual and mythical meaning, the ballgame for the Aztecs was a sport and a pastime played for fun, although in general the Aztec game was a prerogative of the nobles.[80]

Young Aztecs would be taught ballplaying in the calmecac school—and those who were most proficient might become so famous that they could play professionally. Games would frequently be staged in the different city wards and markets—often accompanied by large-scale betting. Diego Durán, an early Spanish chronicler, said that "these wretches... sold their children in order to bet and even staked themselves and became slaves".[33][81]

Since the rubber tree Castilla elastica was not found in the highlands of the Aztec Empire, the Aztecs generally received balls and rubber as tribute from the lowland areas where it was grown. The Codex Mendoza gives a figure of 16,000 lumps of raw rubber being imported to Tenochtitlan from the southern provinces every six months, although not all of it was used for making balls.

In 1528, soon after the Spanish conquest, Cortés sent a troupe of ōllamanime (ballplayers) to Spain to perform for Charles V where they were drawn by the German Christoph Weiditz.[82] Besides the fascination with their exotic visitors, the Europeans were amazed by the bouncing rubber balls.

Pacific coast

Ballcourts, monuments with ballgame imagery and ballgame paraphernalia have been excavated at sites along the Pacific coast of Guatemala and El Salvador including the Cotzumalhuapa nuclear zone sites of Bilbao and El Baúl and sites right at the southeast periphery of the Mesoamerican region such as Quelepa.[83][84]

Caribbean

Batey, a ball game played on many Caribbean islands including Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the West Indies, has been proposed as a descendant of the Mesoamerican ballgame, perhaps through the Maya.[85]

References

- Jeffrey P. Blomster and Víctor E. Salazar Chávez. “Origins of the Mesoamerican ballgame: Earliest ballcourt from the highlands found at Etlatongo, Oaxaca, Mexico”, “Science Advances”, 13 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Fox, John (2012). The ball : discovering the object of the game", 1st ed., New York: Harper. ISBN 9780061881794. Cf. Chapter 4: "Sudden Death in the New World" about the Ulama game.

- Schwartz, Jeremy (December 19, 2008). "Indigenous groups keep ancient sports alive in Mexico". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved December 20, 2008.

- The primary evidence for female ballplayers is in the many apparently female figurines of the Formative period, wearing a ballplayer loincloth and perhaps other gear. In The Sport of Life and Death, editor Michael Whittington says: "It would [therefore] seem reasonable that women also played the game—perhaps in all-female teams—or participated in some yet to be understood ceremony enacted on the ballcourt." (p. 186). In the same volume, Gillett Griffin states that although these figurines have been "interpreted by some as females, in the context of ancient Mesoamerican society the question of the presence of female ballplayers, and their role in the game, is still debated." (p. 158).

- The evidence for ballcourts among the Hohokam is not accepted by all researchers and even the proponents admit that the proposed Hohokam Ballcourts are significantly different from Mesoamerican ones: they are oblong, with a concave (not flat) surface. See Wilcox's article and photo at end of this article.

- Dodson, Steve (May 8, 2006). "POK-TA-POK". Languagehat. Retrieved April 20, 2017.

- Blom, Frans (1932). "The Maya Ball-Game 'Pok-ta-pok', called Tlachtli by the Aztecs". Middle American Research Series Publications. Tulane University. 4: 485–530.

- Graña Behrens, Daniel (2001). "El Juego de Pelota Maya". Mundo Maya (in Spanish). Guatemala: Cholsamaj. pp. 203–228. ISBN 978-99922-56-41-1.

- Espinoza, Mauricio (2002). "El Corazón del Juego: El Juego de Pelota Mesoamericano como Texto Cultural en la Narrativa y el Cine Contemporáneo". Istmo (in Spanish). 4. ISSN 1535-2315. Archived from the original on May 24, 2007.

- Shelton, pp. 109–110. There is wide agreement on game originating in the tropical lowlands, likely the Gulf Coast or Pacific Coast.

- Taladoire (2001) pp. 107–108.

- Hill, Warren D.; Michael Blake; John E. Clark (1998). "Ball court design dates back 3,400 years". Nature. 392 (6679): 878–879. Bibcode:1998Natur.392..878H. doi:10.1038/31837.

- Miller and Taube (1993, p.42)

- These Gulf Coast inhabitants, the Olmeca-Xicalanca, are not to be confused with the Olmec, the name bestowed by 20th century archaeologists on the influential Gulf Coast civilization which had dominated that region three thousand years earlier.

- Ortiz and Rodríguez (1999), pp. 228–232, 242–243.

- Diehl, p. 27

- Uriarte, p. 41, who finds that the juxtaposition at El Manatí of the deposited balls and serpentine staffs (which may have been used to strike the balls) shows that there was already a "well-developed ideological relationship between the [ball]game, power, and serpents."

- Ortiz and Rodríguez (1999), p. 249

- Ortíz, "Las ofrendas de El Manatí y su posible asociación con el juego de pelota: un yugo a destiempo", pp. 55–67 in Uriarte

- Diehl, p. 32, although the identification of a ballcourt within San Lorenzo has not been universally accepted.

- Bradley, Douglas E.; Peter David Joralemon (1993). The Lords of Life: The Iconography of Power and Fertility in Preclassic Mesoamerica (exhibition catalogue, February 2 – April 5, 1992 ed.). Notre Dame, IN: Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame. OCLC 29839104.

- Ekholm, Susanna M. (1991). "Ceramic Figurines and the Mesoamerican Ballgame". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-8165-1180-8. OCLC 22765562.

- Finca Acapulco, San Mateo, and El Vergel, along the Grijalva, have ballcourts dated between 900 and 550 BCE (Agrinier, p. 175).

- Orr, Heather (2005). "Ballgames: The Mesoamerican Ballgame". In Lindsay Jones (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Detroit: Macmillan Reference, Vol. 2. p. 749.

- Cohodas, pp. 251–288

- The 16th century Aztec chronicler Motolinia stated that the games were played by a two-man team vs. a two-man team, three-man team vs. a three-man team, and even a two-man team vs. a three-man team (quoted by Shelton, p. 107).

- Fagan, Brian M. The Seventy Great Inventions of the Ancient World reports that four-man vs four-man team also existed

- Cal State L.A.

- Blanchard, Kendall (2005). The Anthropology of Sport (Revised ed.). Bergin & Garvey. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-89789-329-9.

- Noble, John (2006). Mexico. Lonely Planet. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-74059-744-9.

- Day, p. 66, who further references Diego Durán and Bernardino de Sahagún.

- Shelton, pp. 107–108, who quotes Motolinia.

- Smith, Michael E. (2003). The Aztecs. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 232–233.

- Taladoire, Eric (March 4, 2004). "Could We Speak of the Super Bowl at Flushing Meadows?: La Pelota Mixteca, a Third Pre-Hispanic Ballgame, and its Possible Architectural Context". Ancient Mesoamerica. 14 (2): 319–342. doi:10.1017/S0956536103132142.

- Scott, John F. (2001). "Dressed to Kill: Stone Regalia of the Mesoamerican Ballgame". The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame (Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name organized by the Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC. ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-500-05108-5.

- Dainzu gloves are discussed in Taladoire, 2004

- Filloy Nadal, p. 22.

- Filloy Nadal

- Schwartz states that the ball used by present-day players is 8 pounds (3.6 kg).

- Filloy Nadal, p. 30

- Leyenaar, Ted (2001). "The Modern Ballgames of Sinaloa: a Survival of the Aztec Ullamaliztli". In E. Michael Whittington (ed.). The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame (Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name organized by the Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-0-500-05108-5. OCLC 49029226.

- Coe, Michael D.; Dean Snow; Elizabeth P. Benson (1986). Atlas of Ancient America. New York: Facts on File. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8160-1199-5. OCLC 11518017.

- Cohodas, p. 259.

- Taladoire (2001) p. 98. Note that there are slightly over 200 ballcourts also identified in the American Southwest which are not included in this total, since these are outside Mesoamerica and there is significant discussion whether these areas were used for ballplaying or not.

- Quirarte, pp. 209–210.

- Taladoire (2001) p. 100. Note that Taladoire is measuring the "playing field", while other authors include the benches and other trappings. See Quirarte, pp. 205–208. It is thought that neither the Great Ballcourt nor Tikal's Ceremonial Court were used for ballgames (Scarborough, p. 137).

- Day, p. 75.

- Taladoire and Colsenet.

- Kurjack, Edward B.; Ruben Maldonado C.; Merle Greene Robertson (1991). "Ballcourts of the Northern Maya Lowlands". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1180-8. OCLC 22765562.

- Taladoire (2001) p. 99.

- Day, p. 69.

- Taladoire (2001) p. 97.

- Santley, pp. 14–15.

- Taladoire and Colsenet, p. 174: "We suggest that the ballgame was used as a substitute and a symbol for war."

- Gillespie, p. 340: the ballgame was "a boundary maintenance mechanism between polities".

- Kowalewski, Stephen A.; Gary M. Feinman; Laura Finsten; Richard E. Blanton (1991). "Pre-Hispanic Ballcourts from the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8165-1360-4. OCLC 51873028.

- Day, p. 76

- Taladoire (2001) p. 114.

- Wilkerson, p. 59.

- California State University, Los Angeles, Department of Anthropology, .

- Kubler, p. 147

- Miller, Mary Ellen (2001). "The Maya Ballgame: Rebirth in the Court of Life and Death". The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame (Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name organized by the Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC. ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 20–31. ISBN 978-0-500-05108-5. OCLC 49029226.

- Uriarte, p. 46.

- Schele and Miller, p. 249: "It would not be surprising if the game were rigged"

- Cohodas, p. 255

- Gillespie, p. 321.

- Schele and Miller, p. 243: "occasionally [sacrificial victims'] decapitated heads (sic) were placed in play"

- The ball-as-sun analogy is common in ballgame literature; see, among others, Gillespie, or Blanchard. Some researchers contend that the ball represents not the sun, but the moon.

- Bradley, Douglas E. (1997). Life, Death and Duality: A Handbook of the Rev. Edmund P. Joyce, C.S.C. Collection of Ritual Ballgame Sculpture. Snite Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 1. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame. OCLC 39750624.. Bradley finds that a raised circular dot, or a U-shaped symbol with a dot in the middle, or raised U- or V-shaped areas each represent maize.

- Taladoire and Colsenet, p. 173.

- Velázquez, Primo Feliciano (translator) (1975). Códice Chimalpopoca: Anales de Cuauhtitlan y Leyenda de los Soles. Mexico: UNAM. p. 126.

- These excerpts from the Popol Vuh can be found in Christenson's recent translation or in any work on the Popol Vuh.

- Chinchilla Mazariegos, Oswaldo (2011). Imágenes de la mitología maya. Museo Popol Vuh, Guatemala. pp. 114–118.

- Taladoire (2001) p. 109, who states that Matacapan and Tikal did indeed build ballcourts but only after the fall of Teotihuacan.

- Taladoire (2001) p. 112.

- Taladoire (2001) p. 113.

- The Nahuatl word for the game, ōllamaliztli ([oːllamaˈlistɬi]) was often spelled ullamaliztli—the orthography with "u" is a misrendering of the Náhuatl word caused by the fact that the quality of the nahuatl vowel /ō/ sounds a little like Spanish /u/.

- The name of the present day city of Taxco, Guerrero, comes from the Nahuatl word tlachcho meaning "in the ballcourt".

- De La Garza & Izquierdo, p. 315.

- Wilkerson, p. 45 and others, although there is by no means a universal view; Santley, p. 8: "The game was played by nearly all adolescent and adult males, noble and commoner alike."

- Motolinia, another early Spanish chronicler, also mentioned the heavy betting that accompanied games in Motolinia, Toribio de Benavente (1903). Memoriales. Paris. p. 320.

- De La Garza & Izquierdo, p. 325.

- Kelly, Joyce (1996). An Archaeological Guide to Northern Central America: Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 221, 226. ISBN 978-0-8061-2858-0. OCLC 34658843.

- Andrews, E. Wyllys (1986) [1976]. La Arqueología de Quelepa, El Salvador (in Spanish). San Salvador, El Salvador: Ministerio de Cultura y Comunicaciones. pp. 225–228.

- Alegría, Ricardo E. (1951). "The Ball Game Played by the Aborigines of the Antilles". American Antiquity. Menasha, WI: Society for American Archaeology. 16 (4): 348–352. doi:10.2307/276984. JSTOR 276984. OCLC 27201871.

Cited sources

- Day, Jane Stevenson (2001). "Performing on the Court". In E. Michael Whittington (ed.). The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame (Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name organized by the Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC. ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 65–77. ISBN 978-0-500-05108-5. OCLC 49029226.

- Garza Camino, Mercedes de la; Ana Luisa Izquierdo (1980). "El Ullamaliztli en el Siglo XVI". Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl (in Spanish). 14: 315–333. ISSN 0071-1675.

- Cohodas, Marvin (1991). "Ballgame imagery of the Maya Lowlands: History and Iconography". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1360-4. OCLC 51873028.

- Diehl, Richard (2004). The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. Ancient peoples and places series. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-02119-4. OCLC 56746987.

- Filloy Nadal, Laura (2001). "Rubber and Rubber Balls in Mesoamerica". In E. Michael Whittington (ed.). The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame (Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name organized by the Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC. ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 20–31. ISBN 978-0-500-05108-5. OCLC 49029226.

- Gillespie, Susan D. (1991). "Ballgames and Boundaries". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 317–345. ISBN 978-0-8165-1360-4. OCLC 51873028.

- Ortíz C., Ponciano; María del Carmen Rodríguez (1999). "Olmec Ritual Behavior at El Manatí: A Sacred Space" (PDF). In David C. Grove; Rosemary A. Joyce (eds.). Social Patterns in Pre-Classic Mesoamerica: a symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 9 and 10 October 1993 (Dumbarton Oaks etexts ed.). Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. pp. 225–254. ISBN 978-0-88402-252-7. OCLC 39229716.

- Quirarte, Jacinto (1977). "The Ballcourt in Mesoamerica: Its Architectural Development". In Alan Cordy-Collins; Jean Stern (eds.). Pre-Columbian Art History. Palo Alto, California: Peek Publications. pp. 191–212. ISBN 978-0-917962-41-7.

- Santley, Robert M.; Berman, Michael J.; Alexander, Rami T. (1991). "The Politicization of the Mesoamerican Ballgame and Its Implications for the Interpretation of the Distribution of Ballcourts in Central Mexico". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1180-8. OCLC 22765562.

- Schele, Linda; Miller, Mary Ellen (1986). The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. Fort Worth, Texas: Kimball Art Museum.

- Shelton, Anthony A. (2003). "The Aztec Theatre State and the Dramatization of War". In Tim Cornell; Thomas B. Allen (eds.). War and Games. New York: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-870-9.

- Taladoire, Eric (2001). "The Architectural Background of the Pre-Hispanic Ballgame". The Sport of Life and Death: The Mesoamerican Ballgame (Published in conjunction with an exhibition of the same name organized by the Mint Museum of Art, Charlotte, NC ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson. pp. 97–115. ISBN 978-0-500-05108-5. OCLC 49029226.

- Taladoire, Eric; Colsenet, Benoit (1991). "'Bois Ton Sang, Beaumanior':The Political and Conflictual Aspects of the Ballgame in the Northern Chiapas Area". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1180-8. OCLC 22765562.

- Uriarte, María Teresa, ed. (1992). El juego de pelota en Mesoamérica: raíces y supervivencia (in Spanish). México D.F.: SigloXXI Editores and Casa de Cultura, Gobierno del Estado de Sinaloa. ISBN 978-968-23-1837-5.

- Wilkerson, S. Jeffrey K. (1991). "Then They Were Sacrificed: The Ritual Ballgame of Northeastern Mesoamerica Through Time and Space". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1180-8. OCLC 22765562.

Further reading

- Berdan, Frances F. (2005). The Aztecs of Central Mexico: An Imperial Society. Case Studies in Cultural Anthropology (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-534-62728-7. OCLC 55880584.

- California State University, Los Angeles, Department of Anthropology, "Proyecto Ulama 2003", accessed October 2007.

- Carrasco, David; Scott Sessions (1998). Daily Life of the Aztecs: People of the Sun and Earth. The Greenwood Press "Daily Life Through History". Westport CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29558-1. ISSN 1080-4749. OCLC 37552549.

- Christenson, Allen J. (2007). Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya: The Great Classic of Central American Spirituality. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3839-8.

- Colas, Pierre; Alexander Voss (2006). "A Game of Life and Death – The Maya Ball Game". In Nikolai Grube; Eva Eggebrecht; Matthias Seidel (eds.). Maya: Divine Kings of the Rain Forest. Cologne, Germany: Könemann. pp. 186–191. ISBN 978-3-8331-1957-6. OCLC 71165439.

- Espinoza, Mauricio (2002). "El Corazón del Juego: El Juego de Pelota Mesoamericano como Texto Cultural en la Narrativa y el Cine Contemporáneo". Istmo (in Spanish). 4. ISSN 1535-2315. Archived from the original on May 24, 2007.

- Foster, Lynn V. (2002). Handbook to Life in the Ancient Maya World. Facts on File Library of World History. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4148-0.

- Hosler, Dorothy; Sandra Burkett; Michael Tarkanian (June 18, 1999). "Prehistoric Polymers: Rubber Processing in Ancient Mesoamerica". Science. 284 (5422): 1988–1991. doi:10.1126/science.284.5422.1988. PMID 10373117.

- McKillop, Heather I. (2004). The Ancient Maya: New Perspectives. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-697-2. OCLC 56558696.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art (2002). "Recent Acquisitions, A selection 2001–2002". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. LX (2). ISSN 0026-1521.

- Miller, Mary Ellen; Simon Martin (2004). Courtly Art of the Ancient Maya. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05129-0. OCLC 54799516.

- Wilcox, David R. (1991). "The Mesoamerican Ballgame in the American Southwest". In Vernon Scarborough; David R. Wilcox (eds.). The Mesoamerican Ballgame. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. pp. 101–125. ISBN 978-0-8165-1180-8. OCLC 22765562.

- Zender, Mark (2004). "Glyphs for "Handspan" and "Strike" in Classic Maya Ballgame Texts" (PDF). The PARI Journal. IV (4). ISSN 0003-8113. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008.

External links

![]()

- The First Basketball: The Mesoamerican ballgame NBA Hoops Online

- A figurine showing ballplayer gear, from the Gulf coast's Classic Veracruz culture.

.jpg)