Timeline of hadrosaur research

This timeline of hadrosaur research is a chronological listing of events in the history of paleontology focused on the hadrosauroids, a group of herbivorous ornithopod dinosaurs popularly known as the duck-billed dinosaurs. Scientific research on hadrosaurs began in the 1850s,[1] when Joseph Leidy described the genera Thespesius and Trachodon based on scrappy fossils discovered in the western United States. Just two years later he published a description of the much better-preserved remains of an animal from New Jersey that he named Hadrosaurus.[2]

.jpg)

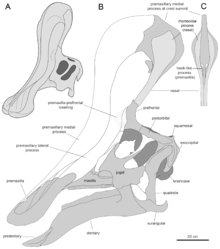

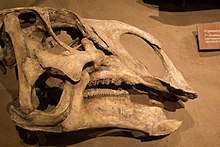

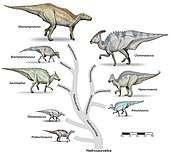

The early 20th century saw such a boom in hadrosaur discoveries and research that paleontologists' knowledge of these dinosaurs "increased by virtually an order of magnitude" according to a 2004 review by Horner, Weishampel, and Forster. This period is known as the great North American Dinosaur rush because of the research and excavation efforts of paleontologists like Brown, Gilmore, Lambe, Parks, and the Sternbergs. Major discoveries included the variety of cranial ornamentation among hadrosaurs as scientist came to characterize uncrested, solid crested, and hollow crested species.[2] Notable new taxa included Saurolophus, Corythosaurus, Edmontosaurus, and Lambeosaurus.[3] In 1942 Richard Swann Lull and Wright published what Horner, Weishampel, and Forster characterized as the "first important synthesis of hadrosaurid anatomy and phylogeny".[2]

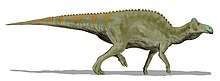

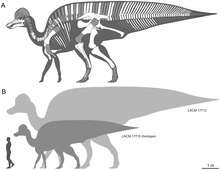

More recent discoveries include gigantic hadrosaurs like Shantungosaurus giganteus from China.[4] At 15 meters in length and nearly 16 metric tons in weight it is the largest known hadrosaur and is known from a nearly complete skeleton.[5]

Hadrosaur research has continued to remain active even into the new millennium. In 2000, Horner and others found that hatchling Maiasaura grew to adult body sizes at a rate more like a mammal's than a reptile. That same year, Case and others reported the discovery of hadrosaur bones in Vega Island, Antarctica. After decades of such dedicated research, hadrosaurs have become one of the best understood group of dinosaurs.[2]

19th century

1850s

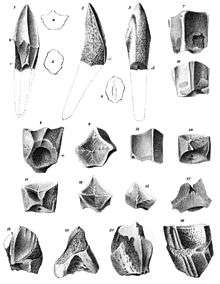

- Joseph Leidy described the new genus and species Thespesius occidentalis. He also described the new genus and species Trachodon mirabilis.[1] Although both species were based on poorly preserved material, this paper was the first to be published on hadrosaurid dinosaurs.

1860s

- Leidy collaborated with artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to mount Hadrosaurus foulkii for the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. This became both the first mounted dinosaur skeleton ever mounted for public display and also one of the most popular exhibits in the history of the Academy. Estimates have the Hadrosaurus exhibit as increasing the number of visitors by up to 50%.[8]

- Edward Drinker Cope described the new genus and species Hypsibema crassicauda.[9]

- Cope named the Hadrosauridae. He observed that the primary distinguishing trait of the group was their dental battery.[10]

- Cope described the new genus and species Ornithotarsus immanis.[6]

1870s

- Othniel Charles Marsh described the new species Hadrosaurus minor.

- Cope described the new species Hadrosaurus cavatus.

- Marsh described the new species Hadrosaurus agilis.[11]

- Cope described the new species Agathaumas milo.[6] He also described the new genus and species Cionodon arctatus.[9]

- Cope described the new species Cionodon stenopsis.[9]

- Cope described the new genus and species Diclonius calamarius. He also described the new species Diclonius pentagonus, Diclonius perangulatus, and Dysganus encaustus.[9]

1880s

- Harry Govier Seeley described the new genus and species Orthomerus dolloi.[1]

- Cope still regarded hadrosaurs as amphibious.[7]

- Richard Lydekker described the new species Trachodon cantabrigiensis.[1]

1890s

- Marsh erected the new genus Claosaurus to house the species Hadrosaurus agilis.[11] He also described the new species Trachodon longiceps.[6]

20th century

1900s

- Franz Nopcsa described the new genus and species Limnosaurus transsylvanicus.[11]

- Lawrence Lambe described the new genus and species Trachodon altidens; in the same volume, he suggested the name Didanodon for the same species, but the validity of this name has been questioned.[12][9] He also described the new species Trachodon marginatus. He also described the new species Trachodon selwyni.[1]

- Nopcsa erected the new genus Telmatosaurus to house the species Limnosaurus transsylvanicus, as the latter genus name was preoccupied .[11]

- George Wieland described the new species Claosaurus affinis.[9]

1910

- Barnum Brown described the new genus Hecatasaurus.[11] He also described the new genus and species Kritosaurus navajovius.[9]

- Brown described the new genus and species Saurolophus osborni.[4]

- Brown described the new genus and species Hypacrosaurus altispinus.[4]

- Cutler excavated a juvenile Gryposaurus now catalogued by the Canadian Museum of Nature as CMN 8784. The site of the excavation has since been designated "quarry 252".[13]

- Winter: Cutler partly prepared the young Gryposaurus specimen, possibly in Calgary while working on dinosaurs for Euston Sisely.[13]

- Brown described the new genus and species Corythosaurus casuarius.[4]

- Lambe described the new genus and species Gryposaurus notabilis.[6]

- Charles H. Sternberg's crew excavated a Corythosaurus from quarry 243 in Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada. The specimen would later be displayed at the Calgary Zoo.[14]

- Matthew observed that fossils of hadrosaur eggs and hatchlings were absent in coastal areas and suggested that hadrosaurs may have preferred nesting grounds further inland. He believed that these inland nesting grounds were actually where hadrosaurs first evolved and therefore to breed, hadrosaurs retraced their ancestors route back to their place of origin. After hatching, the young hadrosaurs would spend some time inland maturing before migrating out to more coastal areas.[15]

- Brown described the new genus and species Prosaurolophus maximus.[6]

- Lambe described the new genus and species Edmontosaurus regalis.[6]

- Lambe described the new genus and species Cheneosaurus tolmanensis.[4]

- Lambe named the Hadrosaurinae.

1920s

- Matthew described the new genus Procheneosaurus.[9]

- Parks described the new species Kritosaurus incurvimanus.[6]

- William Parks described the new genus and species Parasaurolophus walkeri.[9]

- Krausel reported fossil gut contents from an Edmontosaurus annectens mummy. He described the material as including conifer needles and branches, deciduous foliage, and possible small seeds or fruit.[7]

- Abel argued that the plant material Krausel argues was the fossilized remains of the gut contents of an Edmontosaurus annectens was actually deposited by flowing water.[7]

- Charles Whitney Gilmore described the new species Corythosaurus excavatus.[4]

- Parks described the new species Corythosaurus intermedius.[4] He also described the new genus and species Lambeosaurus lambei.[9]

- Gilmore described the new species Thespesius edmontonensis.[6]

- Riabinin described the new species Trachodon amurensis.[1]

- Sternberg described the new species Thespesius saskatchewanensis.[6]

- Wiman described the new genus and species Tanius sinensis.[11]

1930s

- Riabinin described the new species Saurolophus kryschtofovici.[1]

- Riabinin erected the new genus Mandschurosaurus to house the species Trachodon amurensis.[1]

- Parks described the new genus and species Tetragonosaurus erectofrons.[4] He also described the new species Tetragonosaurus praeceps.

- Wiman described the new species Parasaurolophus tubicen.[9]

- Riabinin described the new genus and species Cionodon kysylkumensis.[9]

- Gilmore described the new genus and species Bactrosaurus johnsoni.[11] He also described the new species Mandschurosaurus mongoliensis.[11]

- Parks described the new species Corythosaurus bicristatus and C. brevicristatus.[4]

- Sternberg described the new species Tetragonosaurus cranibrevis.[4] He also described the new species Lambeosaurus clavinitialis and L. magnicristatus.[9]

- Parks described the new species Corythosaurus frontalis.

- Takumi Nagao described the new genus and species Nipponosaurus sachalinensis.[9]

1940s

- Richard Swann Lull and Wright described the new genus Anatosaurus for Claosaurus annectens. They also name the new species Anatosaurus copei.[6]

- Hoffet described the new species Mandschurosaurus laosensis.[1]

- Riabinin described the new species Orthomerus weberi.[1]

- Gilmore and Stewart described the new genus and species Neosaurus missouriensis.[1]

- Gilmore erected the new genus Parrosaurus to house the species Neosaurus missouriensis, as the name Neosaurus was occupied.[1]

1950s

- Rozhdestvensky described the new species Saurolophus angustirostris.[4]

- Sternberg described the new genus and species Brachylophosaurus canadensis.[11]

1960s

- Langston described the new genus and species Lophorhothon atopus.[6]

- Ostrom described the new species Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus.[9]

- Ostrom supported Krausel's 1922 claim that fossil plant material found associated with an Edmontosaurus annectens mummy was actually its gut contents.[7]

- Russel and Chamney studied distribution of hadrosaur in Maastrichtian North America. The concluded that Edmontosaurus regalis lived near the coasts while Hypacrosaurus altispinus and Saurolophus osborni lived slightly more inland.[15]

1970s

- Galton argued that the anatomy of the hadrosaur pelvis was more consistent with a horizontal posture like that seen in modern flightless birds than with the "kangaroo" posture they were often reconstructed in.[7]

- Dodson argued that hadrosaurs may not have fed exclusively on land.[7]

- Dodson found evidence for sexual and ontogenetic dimorphism in two different kinds of lambeosaurine using morphometrics.[16]

- Zhen described the new species Tanius laiyengensis.[9]

- Brett-Surman erected the new genus Gilmoreosaurus to house the species Mandschurosaurus mongoliensis. He also described the new genus and species Secernosaurus koerneri.[11]

- Brett-Surman was unable to determine where hadrosaurs first evolved.[15]

- Horner and Makela described the new genus and species Maiasaura peeblesorum.[6] They argued that hadrosaurs cared for their young for an extended period after hatching.[16]

- Horner argued that hadrosaur fossils found in marine deposited were simply the preserved remains of individuals that had washed out to sea from a terrestrial place of origin.[7]

- Dong described the new genus and species Microhadrosaurus nanshiungensis.[1]

1980s

- Hotton argued that some hadrosaurs may have migrated seasonally in a north-south direction.

.jpg)

- Teresa Maryańska and Osmolska described the new genus and species Barsboldia sicinskii.[4]

- Morris described the new species Lambeosaurus laticaudus.[9]

- Suslov and Shilin described the new genus and species Arstanosaurus akkurganensis.[9]

- Carpenter disputed the idea that hadrosaurs only nested in upland environments, instead arguing that fossil hadrosaur eggs and hatchlings were only absent from coastal deposits because the chemistry of the ancient soils were simply too acidic to preserve them.[7]

- Thulborn argued that hadrosaurs may have been able to run at speeds of up to 14–20 km/hr for sustained periods.[7]

- Horner observed that Maiasaura peeblesorum is only known to have lived in the upper regions of contemporary coastal plains.[15]

- Weishampel described hadrosaur chewing and cranial kinetics.[7]

- Weishampel and Weishampel reported the presence of hadrosaur remains on the Antarctic Peninsula.[15]

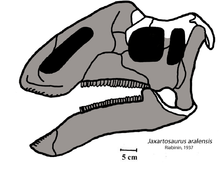

- Wu described the new genus and species Jaxartosaurus fuyuensis.[9]

- Milner and Norman argued that hadrosaurs evolved in Asia.[15]

- Horner observed that fossil eggs and hadrosaur hatchlings were common in sediments deposited in the upper regions of what were once coastal plains.[15]

- Weishampel described hadrosaur chewing and cranial kinetics.[7]

- Norman described hadrosaur chewing and cranial kinetics.[7]

- Weishampel argued that hadrosaurs fed mainly on vegetation of 2 m in height or less but had a maximum browsing height of 4 m.[7]

- Bonaparte and others described the new species Kritosaurus australis.[4]

- Norman and Weishampel described hadrosaur chewing and cranial kinetics.[7]

- Horner observed that fossil eggs and hadrosaur hatchlings were common in sediments deposited in the upper regions of what were once coastal plains.[15]

- Farlow argued that their highly developed chewing abilities and large gut volumes meant hadrosaurs werehighly adapted to feeding on nutrient poor, fibrous vegetation.[7]

- Horner described the new species Brachylophosaurus goodwini.[11]

1990s

- Brett-Surman described the new genus Anatotitan for Anatosaurus copei.

- Horner argued that the hadrosaurids were not a natural group, and instead that the two major groups of hadrosaurs, the generally uncrested hadrosaurines and the crested lambeosaurs had separate origins within the Iguanodontia. Horner though that the uncrested hadrosaurs were descended from a relative of Iguanodon, while the crested lambeosaurs were descended from a relative of Ouranosaurus. However, this proposal would find no support in any subsequent research publication.[10]

- Weishampel and Horner found the Hadrosauridae to be a natural group after all.[10] They also found cladistic support for the traditional division of Hadrosauridae into the subfamilies Hadrosaurinae and Lambeosaurinae.[10]

- Weishampel reported the presence of hadrosaurs on the Antarctic peninsula.[15]

- Bolotsky and Kurzanov described the new genus and species Amurosaurus riabinini.[4]

- Horner described the new species Gryposaurus latidens. He also described the new species Prosaurolophus blackfeetensis.[6]

- Hunt and Lucas described the new genus and species Anasazisaurus horneri.[11] They also described the new genus and species Naashoibitosaurus ostromi.[6]

- Weishampel, Norman, and Griogescu named the clade Euhadrosauria.[11]

- Weishampel and others proposed a node-based definition for the Hadrosauridae: the descendants of the most recent common ancestor shared by Telmatosaurus and Parasaurolophus.[17] They found the hadrosaurs to be a natural group, contrary to Horner's 1990 arguments that the hadrosaur subfamilies were descended from different kinds of iguanodont.[10] They also found cladistic support for the traditional division of Hadrosauridae into the subfamilies Hadrosaurinae and Lambeosaurinae.[10]

- Clouse and Horner reported the presence of hadrosaur egg, embryo and hatchling fossils from the Judith River Formation of Montana. Since these sediments were deposited in a low-lying coastal plain, the researchers' discovery contradicted previous hypotheses that hadrosaurs either didn't nest in lowland areas or that local ancient soil was too acidic to preserve them.[7]

- Horner and Currie described the new species Hypacrosaurus stebingeri.[4]

- Chin and Gill described Maiasaura peeblesorum coprolites from an ancient nesting ground of that species. The coprolites were "blocky", irregularly-shaped masses that preserved plant fragments. The researchers identified it as feces because the masses contained fossilized dung beetle burrows. The plant material suggested a diet consisting mainly of conifer stems.[7]

- Forster found the hadrosaurs to be a natural group, contrary to Horner's 1990 arguments that the hadrosaur subfamilies were descended from different kinds of iguanodont.[10] They also found cladistic support for the traditional division of Hadrosauridae into the subfamilies Hadrosaurinae and Lambeosaurinae.[10] She preferred to define the Hadrosauridae as the most recent common ancestor of the hadrosaurines and lambeosaurines and all of its descendants. Unlike the definition used by Weishampel and others in 1993, this definition excluded Telmatosaurus.[18]

- Sereno found the hadrosaurs to be a natural group, contrary to Horner's 1990 arguments that the hadrosaur subfamilies were descended from different kinds of iguanodont.[10]

21st century

2000s

- Godefroit, Zan, and Jin described the new genus and species Charonosaurus jiayinensis.[4]

- Case and others reported the presence of hadrosaurs on the Antarctica peninsula.[2] The remains studied were found on Vega Island and represent the southernmost known hadrosaur fossils. When the animals were still alive, this site was probably at a latitude of about 65 degrees South.[15]

- Horner and others studied the histology of Maiasaura peeblesorum bones. They found that Maiasaura only took 8–10 years to reach adult body size. A 7 metres (23 ft) adult Maiasaura could have an adult body mass of over 2,000 kilograms (4,400 lb) despite hatching at a length of about half a meter and with a body mass of less than a kilogram. This disparity implies a rate or growth similar to those found in modern mammals.[7]

- Horner and others published additional research on the histology of Maiasaura peeblesorum bones.[7]

- You and others described the new genus and species Equijubus normani.[19]

- Kobayashi and Azuma described the new genus and species Fukuisaurus tetoriensis.[20]

- Godefroit, Bolotsky, and Alifanov described the new genus and species Olorotitan arharensis.[9]

- Bolotsky and Godefroit described the new genus and species Kerberosaurus manakini.[21]

- Godefroit, Li, and Shang described the new genus and species Penelopognathus weishampeli.[22]

- Prieto-Márquez and others described the new genus and species Koutalisaurus kohlerorum.[23]

- Gilpin and others described the new genus and species Cedrorestes crichtoni.[24]

- Mo and others described the new genus and species Nanningosaurus dashiensis.[25]

- Zhao and others described the new genus and species Zhuchengosaurus maximus.[26]

- Godefroit and others described the new genus and species Sahaliyania elunchunorum and the new genus and species Wulagasaurus dongi.[27]

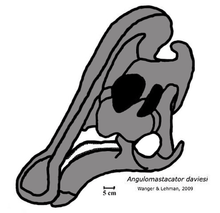

- Wagner and Lehman described the new genus and species Angulomastacator daviesi.[28]

- Pereda-Suberbiola and others described the new genus and species Arenysaurus ardevoli.[29]

- Sues and Averianov described the new genus and species Levnesovia transoxiana.[30]

- Dalla Vecchia described the new genus and species Tethyshadros insularis.[31]

2010s

- Cruzado-Caballero and others described the new genus and species Blasisaurus canudoi.[32]

- Prieto-Márquez described the new genus and species Glishades ericksoni.[33]

- Juárez Valieri and others described the new genus and species Willinakaqe salitralensis.[34]

- Gates and others described the new genus and species Acristavus gagslarsoni.[35]

- Godefroit and others described the new genus and species Batyrosaurus rozhdestvenskyi.[36]

- Ramírez-Velasco and others described the new genus and species Huehuecanauhtlus tiquichensis.[37]

- Godefroit and others described the new genus and species Kundurosaurus nagornyi.[38]

- Coria, Riga and Casadío described the new genus and species Lapampasaurus cholinoi.[39]

- Prieto-Márquez and Brañas described the new genus and species Latirhinus uitstlani.[40]

- Prieto-Márquez Chiappe, and Joshi described the new genus and species Magnapaulia.[41]

- Prieto-Márquez and others described the new genus and species Canardia garonnensis.[42]

- Phil R. Bell and Kirstin S. Brink described the new genus and species Kazaklambia convincens.[43]

- Prieto-Márquez and Wagner described the new species Saurolophus morrisi.[44]

- Wang and others escribed the new genus and species Yunganglong datongensis.[45]

- Prieto-Márquez and others described the new genus Augustynolophus.[46]

- Gates and Scheetz described the new genus and species Rhinorex condrupus.[47]

- Xing and others described the new genus and species Zhanghenglong yangchengensis.[48]

- Gates and others described the new genus Adelolophus.[49]

- You, Li, and Dodson described the new genus Gongpoquansaurus.[50]

- Shibata and Azuma described the new genus and species Koshisaurus katsuyama.[51]

- Mori, Druckenmiller and Erickson described the new genus and species Ugrunaaluk kuukpikensis.[52]

- Freedman Fowler, and Horner described the new genus and species Probrachylophosaurus.[53]

- Shibata and others described the new genus and species Sirindhorna khoratensis.[54]

- Xu and others described the new genus and species Datonglong.[55]

- Wang and others described the new genus and species Zuoyunlong.[56]

- Prieto-Marquez, Erickson and Ebersole described the new genus and species Eotrachodon orientalis[57]

- Cruzado-Caballero and Powell described the new genus and species Bonapartesaurus rionegrensis.

- Study of corpolites by Chin, Feldmann & Tashman show hadrosaurs occasionally consumed decaying wood and crustaceans <ref>Chin, Feldmann & Tashman. (2017) Consumption of crustaceans by megaherbivorous dinosaurs: dietary flexibility and dinosaur life history strategies.</ref>

- Gates and others described the new genus and species Choyrodon barsboldi.[58]

- Prieto-Márquez and others described the new genus and species Adynomosaurus arcanus.[59]

- Zhang and others described the new genus and species Laiyangosaurus youngi.[60]

- Tsogtbaatar and others described the new genus and species Gobihadros mongoliensis.[61]

- Prieto-Márquez, Wagner, and Lehman described the new genus and species Aquilarhinus palimentus.[62]

- Kobayashi and others described the new genus and species Kamuysaurus japonicus.

- A study on the nature of the fluvial systems of Laramidia during the Late Cretaceous, as indicated by data from vertebrate and invertebrate fossils from the Kaiparowits Formation of southern Utah, and on the behavior of hadrosaurid dinosaurs over these landscapes, will be published by Crystal et al. (2019).[63]

- A study on the osteology and phylogenetic relationships of "Tanius laiyangensis" is published by Zhang et al. (2019).[64]

- A study on the bone histology of tibiae of Maiasaura peeblesorum, focusing on the composition, frequency and cortical extent of localized vascular changes, is published by Woodward (2019).[65]

- Three juvenile specimens of Prosaurolophus maximus, providing new information on the ontogeny of this taxon, are described from the Bearpaw Formation (Alberta, Canada) by Drysdale et al. (2019).[66]

- A study on the impact of bone tissue structure, early diagenetic regimes and other taphonomic variables on the preservation potential of soft tissues in vertebrate fossils, as indicated by data from fossils of Edmontosaurus annectens from the Standing Rock Hadrosaur Site (Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation, South Dakota), is published by Ullmann, Pandya & Nellermoe (2019), who report the first recovery of osteocytes and vessels from a fossil vertebral centrum and ossified tendons.[67]

- The first definitive lambeosaurine fossil (an isolated skull bone) is described from the Liscomb Bonebed of the Prince Creek Formation (Alaska, United States) by Takasaki et al. (2019).[68]

- Traces preserved on a tail vertebra of a hadrosaurid dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation (Montana, United States) are described by Peterson & Daus (2019), who interpret their finding as feeding traces produced by a late-stage juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex.[69]

Footnotes

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Table 20.1: Hadrosauridae", page 443.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Introduction", page 438.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Table 20.1: Hadrosauridae", pages 439–442.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Table 20.1: Hadrosauridae", page 441.

- Lucas (2001); "Nemegtian Vertebrates", page 181.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Table 20.1: Hadrosauridae", page 440.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Paleoecology, Biogeography, and Paleobiology", page 462.

- Weishampel and Young (1996); "Haddonfield Hadrosaurus", page 71.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Table 20.1: Hadrosauridae", page 442.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Systematics and Evolution", page 457.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Table 20.1: Hadrosauridae", page 439.

- Lund, E.K. and Gates, T.A. (2006). "A historical and biogeographical examination of hadrosaurian dinosaurs." pp. 263 in Lucas, S.G. and Sullivan, R.M. (eds.), Late Cretaceous vertebrates from the Western Interior. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 35.

- Tanke (2010); "Note 4," page 544.

- Tanke (2010); "Note 9," page 546.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Paleoecology, Biogeography, and Paleobiology", page 461.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Paleoecology, Biogeography, and Paleobiology", page 463.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Systematics and Evolution", pages 457–458.

- Horner, Weishampel, and Forster (2004); "Systematics and Evolution", page 458.

- You et al. (2003); "Abstract", page 347.

- Kobayashi and Azuma (2003); "Abstract", page 166.

- Bolotsky and Godefroit (2004); "Abstract", page 351.

- Godefroit, Li, and Shang (2005); "Abstract", page 697.

- Prieto-Márquez et al. (2006); "Abstract", page 929.

- Gilpin, DiCroce and Carpenter (2007); "Abstract", page 79.

- Mo et al. (2007); "Abstract", page 550.

- Zhao et al. (2007); "Abstract", page 111.

- Godefroit et al. (2008); "Abstract", page 47.

- Wagner and Lehman (2009); "Abstract", page 605.

- Pereda-Suberbiola et al. (2009); "Abstract", page 559.

- Sues and Averianov (2009); "Abstract", page 2549.

- Dalla Vecchia (2009); "Abstract", page 1100.

- Cruzado-Caballero, Pereda-Suberbiola, and Ruiz-Omeñaca (2010); "Abstract", page 1507.

- Prieto-Márquez (2010); "Abstract", page 1.

- Juárez Valieri et al. (2010); "Abstract", page 217.

- Gates et al. (2011); "Abstract", page 798.

- Godefroit et al. (2012); "Abstract", page 335.

- Ramírez-Velasco et al. (2012); "Abstract", page 379.

- Godefroit et al. (2012); "Abstract", page 438.

- Coria, Riga and Casadío (2012); "Abstract", page 552.

- Prieto-Márquez and Brañas (2012); "Abstract", page 607.

- Prieto-Márquez, Chiappe, and Joshi (2012); "Abstract", page 1.

- Prieto-Márquez et al. (2013); "Canardia gen. nov", page 5.

- Bell and Brink (2013); "Abstract", page 265.

- Prieto-Márquez and Wagner (2013); "Abstract", page 255.

- Wang et al. (2013); "Abstract", page 1.

- Prieto-Márquez et al. (2014); "Abstract", page 1.

- Gates and Scheetz (2014); "Abstract", page 798.

- Xing et al. (2014); "Abstract", page 1.

- Gates et al. (2014); "Abstract", page 156.

- You, Li, and Dodson (2014); "Abstract", page 73.

- Shibata and Azuma (2015); "Abstract", page 421.

- Mori, Druckenmiller and Erickson (2015); "Abstract".

- Freedman Fowler and Horner (2015); in passim.

- Shibata et al. (2015); in passim.

- Xu et al. (2016); in passim.

- Wang et al. (2016); in passim.

- Prieto-Márquez et al. (2016); in passim.

- Terry A. Gates; Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar; Lindsay E. Zanno; Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig; Mahito Watabe (2018). "A new iguanodontian (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Early Cretaceous of Mongolia". PeerJ. 6: e5300. doi:10.7717/peerj.5300. PMC 6078070. PMID 30083450.

- Prieto-Márquez, Albert; Fondevilla, Víctor; Sellés, Albert G.; Wagner, Jonathan R.; Galobart; Àngel (2019). "Adynomosaurus arcanus, a new lambeosaurine dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Ibero-Armorican Island of the European Archipelago". Cretaceous Research. 96: 19–37. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.12.002.

- Jialiang Zhang; Xiaolin Wang; Qiang Wang; Shunxing Jiang; Xin Cheng; Ning Li; Rui Qiu (2019). "A new saurolophine hadrosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Shandong, China". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 91 (Suppl. 2): e20160920. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201720160920. PMID 28876393.

- Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar; David B. Weishampel; David C. Evans; Mahito Watabe (2019). "A new hadrosauroid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Late Cretaceous Baynshire Formation of the Gobi Desert (Mongolia)". PLOS ONE. 14 (4): e0208480. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208480. PMC 6469754. PMID 30995236.

- Prieto-Márquez, Albert; Wagner, Jonathan R.; Lehman, Thomas (2019). "An unusual 'shovel-billed' dinosaur with trophic specializations from the early Campanian of Trans-Pecos Texas, and the ancestral hadrosaurian crest". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology: 1–38. doi:10.1080/14772019.2019.1625078.

- Victoria F. Crystal; Erica S.J. Evans; Henry Fricke; Ian M. Miller; Joseph J.W. Sertich (2019). "Late Cretaceous fluvial hydrology and dinosaur behavior in southern Utah, USA: Insights from stable isotopes of biogenic carbonate". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 516: 152–165. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.11.022.

- Yu‐Guang Zhang; Ke‐Bai Wang; Shu‐Qing Chen; Di Liu; Hai Xing (2019). "Osteological re‐assessment and taxonomic revision of "Tanius laiyangensis" (Ornithischia: Hadrosauroidea) from the Upper Cretaceous of Shandong, China". The Anatomical Record. 303 (4): 790–800. doi:10.1002/ar.24097. PMID 30773831.

- Holly N. Woodward (2019). "Maiasaura (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) tibia osteohistology reveals non-annual cortical vascular rings in young of the year". Frontiers in Earth Science. 7: Article 50. doi:10.3389/feart.2019.00050.

- Eamon T. Drysdale; François Therrien; Darla K. Zelenitsky; David B. Weishampel; David C. Evans (2019). "Description of juvenile specimens of Prosaurolophus maximus (Hadrosauridae: Saurolophinae) from the Upper Cretaceous Bearpaw Formation of southern Alberta, Canada, reveals ontogenetic changes in crest morphology". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. in press (6): e1547310. doi:10.1080/02724634.2018.1547310.

- Paul V. Ullmann; Suraj H. Pandya; Ron Nellermoe (2019). "Patterns of soft tissue and cellular preservation in relation to fossil bone tissue structure and overburden depth at the Standing Rock Hadrosaur Site, Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation, South Dakota, USA". Cretaceous Research. 99: 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.02.012.

- Ryuji Takasaki; Anthony R. Fiorillo; Yoshitsugu Kobayashi; Ronald S. Tykoski; Paul J. McCarthy (2019). "The first definite lambeosaurine bone from the Liscomb Bonebed of the Upper Cretaceous Prince Creek Formation, Alaska, United States". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): Article number 5384. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-41325-8. PMC 6440964. PMID 30926823.

- Joseph E. Peterson; Karsen N. Daus (2019). "Feeding traces attributable to juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex offer insight into ontogenetic dietary trends". PeerJ. 7: e6573. doi:10.7717/peerj.6573. PMC 6404657. PMID 30863686.

References

- Bell, P. R.; Brink, K. S. (2013). "Kazaklambia convincens comb. nov., a primitive juvenile lambeosaurine from the Santonian of Kazakhstan". Cretaceous Research. 45: 265–274. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2013.05.003.

- Bolotsky, Y.L.; Godefroit, P. (2004). "A new hadrosaurine dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Far Eastern Russia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (2): 351–365. doi:10.1671/1110.

- Rodolfo A. Coria, Bernardo González Riga and Silvio Casadío (2012). "Un nuevo hadrosáurido (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) de la Formación Allen, provincia de La Pampa, Argentina". Ameghiniana. in press.

- Cruzado-Caballero, Penélope; Xabier Pereda-Suberbiola; José Ignacio Ruiz-Omeñaca (2010). "Blasisaurus canudoi gen. et sp. nov., a new lambeosaurine dinosaur (Hadrosauridae) from the Latest Cretaceous of Arén (Huesca, Spain)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 47 (12): 1507–1517. doi:10.1139/E10-081.

- Dalla Vecchia, F. M. (2009). "Tethyshadros insularis, a new hadrosauroid dinosaur (Ornithischia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Italy". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (4): 1100–1116. doi:10.1671/039.029.0428.

- Elizabeth A. Freedman Fowler & John R. Horner (2015). "A New Brachylophosaurin Hadrosaur (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) with an Intermediate Nasal Crest from the Campanian Judith River Formation of Northcentral Montana". PLOS ONE. 10 (11): e0141304. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141304. PMC 4641681. PMID 26560175.

- Gates, T.A.; Horner, J.R.; Hanna, R.R.; Nelson, C.R. (2011). "New unadorned hadrosaurine hadrosaurid (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) from the Campanian of North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (4): 798–811. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.577854.

- Gates, T. A.; Scheetz, R. (2014). "A new saurolophine hadrosaurid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Campanian of Utah, North America". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 13 (8): 711–725. doi:10.1080/14772019.2014.950614.

- Terry A. Gates, Zubair Jinnah, Carolyn Levitt and Michael A. Getty (2014). "New hadrosaurid (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) specimens from the lower-middle Campanian Wahweap Formation of southern Utah". In David A. Eberth; David C. Evans (eds.). Hadrosaurs: Proceedings of the International Hadrosaur Symposium. Indiana University Press. pp. 156–173. ISBN 978-0-253-01385-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Gilpin, David; DiCroce, Tony; Carpenter, Kenneth (2007). "A possible new basal hadrosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation of Eastern Utah". In Carpenter, K. (ed.). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 79–89. ISBN 978-0-253-34817-3.

- Godefroit, P.; Li, H.; Shang, C.Y. (2005). "A new primitive hadrosauroid dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia (P.R. China)"". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 4 (8): 697–705. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2005.07.004.

- Godefroit, Pascal; Hai Shulin; Yu Tingxiang; Lauters, Pascaline (2008). "New hadrosaurid dinosaurs from the uppermost Cretaceous of north−eastern China" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 53 (1): 47–74. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0103.

- Pascal Godefroit, François Escuillié, Yuri L. Bolotsky and Pascaline Lauters (2012). "A New Basal Hadrosauroid Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of Kazakhstan". In Godefroit, P. (ed.). Bernissart Dinosaurs and Early Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. Indiana University Press. pp. 335–358.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Godefroit, P.; Bolotsky, Y. L.; Lauters, P. (2012). Joger, Ulrich (ed.). "A New Saurolophine Dinosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of Far Eastern Russia". PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e36849. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036849. PMC 3364265. PMID 22666331.

- Horner, John R.; Weishampel, David B.; Forster, Catherine A. (2004). "Hadrosauridae". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmolska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2 ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 438–463. ISBN 978-0520254084.

- Rubén D. Juárez Valieri, José A. Haro, Lucas E. Fiorelli and Jorge O. Calvo (2010). "A new hadrosauroid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Allen Formation (Late Cretaceous) of Patagonia, Argentina" (PDF). Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales N.s. 11 (2): 217–231. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-03.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kobayashi, Y.; Azuma, Y. (2003). "A new iguanodontian (Dinosauria; Ornithopoda), form the lower Cretaceous Kitadani Formation of Fukui Prefecture, Japan". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (1): 166–175. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[166:anidof]2.0.co;2.

- Lucas, Spencer G. (2001-11-15). Chinese Fossil Vertebrates. Columbia University Press. p. 320(p. 34). ISBN 978-0231084826.

- Mo J.; Zhao Z.; Wang W.; Xu X. (2007). "The first hadrosaurid dinosaur from southern China". Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition). 81 (4): 550–554. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6724.2007.tb00978.x.

- Mori, Hirotsugu; Druckenmiller, Patrick S. & Erickson, Gregory M. (2015). "A new Arctic hadrosaurid from the Prince Creek Formation (lower Maastrichtian) of northern Alaska". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61 (In press). doi:10.4202/app.00152.2015.

- Pereda-Suberbiola, Xabier; José Ignacio Canudo; Penélope Cruzado-Caballero; José Luis Barco; Nieves López-Martínez; Oriol Oms; José Ignacio Ruiz-Omeñaca (2009). "The last hadrosaurid dinosaurs of Europe: A new lambeosaurine from the Uppermost Cretaceous of Aren (Huesca, Spain)" (PDF). Comptes Rendus Palevol. 8 (6): 559–572. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2009.05.002.

- Prieto-Marquez, A.; Gaete, R.; Rivas, G.; Galobart, Á.; Boada, M. (2006). "Hadrosauroid dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Spain: Pararhabdodon isonensis revisited and Koutalisaurus kohlerorum, gen. et sp. nov". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 929–943. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[929:hdftlc]2.0.co;2.

- Prieto-Márquez, Albert (2010). "Glishades ericksoni, a new hadrosauroid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Late Cretaceous of North America" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2452: 1–17. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2452.1.1.

- Prieto-Márquez, Albert; Serrano Brañas, Claudia Inés (2012). "Latirhinus uitstlani, a 'broad-nosed' saurolophine hadrosaurid (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) from the late Campanian (Cretaceous) of northern Mexico". Historical Biology. 24 (6): 607–619. doi:10.1080/08912963.2012.671311.

- Prieto-Márquez, A.; Chiappe, L. M.; Joshi, S. H. (2012). Dodson, Peter (ed.). "The lambeosaurine dinosaur Magnapaulia laticaudus from the Late Cretaceous of Baja California, Northwestern Mexico". PLOS ONE. 7 (6): e38207. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038207. PMC 3373519. PMID 22719869.

- Prieto-Márquez, A.; Dalla Vecchia, F. M.; Gaete, R.; Galobart, À. (2013). Dodson, Peter (ed.). "Diversity, Relationships, and Biogeography of the Lambeosaurine Dinosaurs from the European Archipelago, with Description of the New Aralosaurin Canardia garonnensis". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e69835. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069835. PMC 3724916. PMID 23922815.

- Prieto-Márquez, Albert; Wagner, Jonathan R.; Bell, Phil R.; Chiappe, Luis M. (2014). "The late-surviving 'duck-billed' dinosaur Augustynolophus from the upper Maastrichtian of western North America and crest evolution in Saurolophini". Geological Magazine. 152 (2): 225–241. doi:10.1017/S0016756814000284.

- Prieto-Márquez, Albert; Erickson, Gregory M.; Ebersole, Jun A. (2016). "A primitive hadrosaurid from southeastern North America and the origin and early evolution of 'duck-billed' dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (2): e1054495. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1054495.

- Prieto-Márquez, A.; Wagner, J.R. (2013). "A new species of saurolophine hadrosaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of the Pacific coast of North America". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 58 (2): 255–268. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0049.

- Angel Alejandro Ramírez-Velasco, Mouloud Benammi, Albert Prieto-Márquez, Jesús Alvarado Ortega and René Hernández-Rivera (2012). "Huehuecanauhtlus tiquichensis, a new hadrosauroid dinosaur (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda) from the Santonian (Late Cretaceous) of Michoacán, Mexico". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 49 (2): 379–395. doi:10.1139/e11-062.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Masateru Shibata, Pratueng Jintasakul, Yoichi Azuma and Hai-Lu You (2015). "A New Basal Hadrosauroid Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Khok Kruat Formation in Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Northeastern Thailand". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0145904. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0145904. PMC 4696827. PMID 26716981.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Shibata, Masateru; Azuma, Yoichi (2015). "New basal hadrosauroid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Lower Cretaceous Kitadani Formation, Fukui, central Japan" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3914 (4): 421–40. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3914.4.3. PMID 25661952.

- Sues, Hans-Dieter; Averianov, Alexander (2009). "A new basal hadrosauroid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Uzbekistan and the early radiation of duck-billed dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1667): 2549–2555. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0229. PMC 2686654. PMID 19386651.

- Tanke, D. H. (2010). "Lost in plain sight: rediscovery of William E. Cutler's missing Eoceratops". In Ryan, M. J.; Chinnery-Allgeier, B. J.; Eberth, D. A. (eds.). New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium. Life of the Past. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 541–550. ISBN 978-0253353580.

- Wagner, Jonathan R.; Lehman, Thomas M. (2009). "An Enigmatic New Lambeosaurine Hadrosaur (Reptilia: Dinosauria) from the Upper Shale Member of the Campanian Aguja Formation of Trans-Pecos Texas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (2): 605–611. doi:10.1671/039.029.0208.

- Weishampel, David B.; Young, L. (1996). Dinosaurs of the East Coast. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Wang, R. F.; You, H. L.; Xu, S. C.; Wang, S. Z.; Yi, J.; Xie, L. J.; Jia, L.; Li, Y. X. (2013). Evans, David C (ed.). "A New Hadrosauroid Dinosaur from the Early Late Cretaceous of Shanxi Province, China". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e77058. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077058. PMC 3800054. PMID 24204734.

- Run-Fu Wang, Hai-Lu You, Suo-Zhu Wang, Shi-Chao Xu, Jian Yi, Li-Juan Xie, Lei Jia and Hai Xing (2016). "A second hadrosauroid dinosaur from the early Late Cretaceous of Zuoyun, Shanxi Province, China". Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology. 29: 1–8. doi:10.1080/08912963.2015.1118688.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Xing, H.; Wang, D.; Han, F.; Sullivan, C.; Ma, Q.; He, Y.; Hone, D. W. E.; Yan, R.; Du, F.; Xu, X. (2014). "A New Basal Hadrosauroid Dinosaur (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) with Transitional Features from the Late Cretaceous of Henan Province, China". PLOS ONE. 9 (6): e98821. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098821. PMC 4047018. PMID 24901454.

- Xu, S-C.; You, H-L.; Wang, J-W.; Wang, S-Z.; Yi, J.; Jia, L. (2016). "A new hadrosauroid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of Tianzhen, Shanxi Province, China". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 54 (1): 67–78.

- You, H.-I.; Li, D.-Q.; Dodson, P. (2014). "Gongpoquansaurus mazongshanensis (Lü, 1997) comb. nov. (Ornithischia: Hadrosauroidea) from the Early Cretaceous of Gansu Province, Northwestern China". In Eberth, David A.; Evans, David C. (eds.). Hadrosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 73–76. ISBN 978-0-253-01390-3.

- You, Luo; Shubin, Witmer; Tang; Tang (2003). "The earliest-known duck-billed dinosaur from deposits of late Early Cretaceous age in northwest China and hadrosaurid evolution". Cretaceous Research. 24 (3): 347–353. doi:10.1016/s0195-6671(03)00048-x.

- Zhao, X.; Li, D.; Han, G.; Hao, H.; Liu, F.; Li, L.; Fang, X. (2007). "Zhuchengosaurus maximus from Shandong Province". Acta Geoscientia Sinica. 28 (2): 111–122. doi:10.1007/s10114-005-0808-x.

External links