Qira'at

In Islam, Qira'at (Arabic: قِراءة, lit. 'recitations or readings') are "the different linguistic, lexical, phonetic, morphological and syntactical forms permitted with reciting the Quran".[1] There are ten different recognised schools of qira'at, each one deriving its name from a noted Quran reciter or "reader" (qāriʾ pl. qāriʾūna).[Note 1] While these Quran readers lived in the second and third century of Islam, the scholar who first approved of the qira'at (Abu Bakr Ibn Mujāhid) lived a century later, so that the people who passed down the readings (the "transmitters") are part of the system of qira'at (qira'at pass to riwaya who have turuq or lines of transmission, and passed down to wujuh i.e. the next line of transmission).[3] Thus it is more accurate to say about a reading of the Quran, "this is the riwaya of Hafs", and not "this is Hafs" (Hafs being the Qira'at used by most of the Muslim world).[3]

| Quran |

|---|

|

|

Qira'at are sometimes confused with Ahruf—both being variants of the Quran and both said to have seven different varieties.[4] However varieties of ahruf were discontinued by order of caliph Uthman sometime in the mid-7th century CE when "the Quran began to be read in only one harf (variation)",[5] while the seven readings of the Qira'at were noted by Abu Bakr Ibn Mujāhid and canonized in the 8th century CE.[6] A number of hadith provide an Islamic basis for the different variants (Ahruf) of the Quran. These include one where Muhammad listens to recitations of various companions and approves of each of them;[4] where he corrects Umar's berating another companion's recitation saying the "Quran has been revealed in seven Ahruf";[7] or claim Muhammad asked the angel Jibreel to teach him different styles of recitation until he had learned seven.[8]

Differences between Qira'at are slight and include differences in stops,[Note 2] vowels,[Note 3] letters,[Note 4] and sometimes entire words.[Note 5] Recitation should be in accordance with rules of pronunciation, intonation, and caesuras established by Muhammad and first recorded during the eighth century CE. The maṣḥaf Quran that is in "general use" throughout almost all the Muslim world today, is a 1924 Egyptian edition based on the Qira'at "reading of Ḥafṣ on the authority of `Asim", (Ḥafṣ being the Rawi, or "transmitter", and `Asim being the Qari or "reader").[10] Each melodic passage centers on a single tone level, but the melodic contour and melodic passages are largely shaped by the reading rules (creating passages of different lengths, whose temporal expansion is defined with caesuras). Skilled readers may read professionally for urban mosques.

History

According to Islamic belief, the Qur'an is recorded in the preserved tablet in heaven,[11] and was revealed to the prophet Muhammad by the angel Gabriel.

Quranic orthography

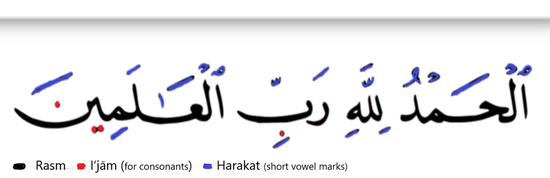

Early manuscripts of the Qur’ān did not use diacritics either for vowels (Ḥarakāt) or to distinguish the different values of the rasm (I‘jām') [see the graphic to the right], -- or at least used them "only sporadically and insufficiently to create a completely unambigous text".[14] These early manuscripts included the "official" copy of the Quran created by ‘Uthman, according to the Saudi Salafi website IslamQA:

When ‘Uthmaan made copies of the Qur’aan, he did so according to one style (harf), but he omitted the dots and vowel points so that some other styles could also be accommodated. So the Mus'haf that was copied in his time could be read according to other styles, and whatever styles were accommodated by the Mus'haf of ‘Uthmaan remained in use, and the styles that could not be accommodated fell into disuse. The people had started to criticize one another for reciting differently, so ‘Uthmaan united them by giving them one style of the Qur’aan.[4]

Gradual steps were taken to improve the orthography of the Quran, in the first century with dots to distinguish similarly-shaped consonants, followed by marks (to indicate different vowels) and nunation in different-coloured ink from the text (Abu'l Aswad ad-Du'alî (d. 69 AH/688 CE). (Not related to the colours used in the graphic to the right.) Later the different colours were replaced with marks used in written Arabic today.

Recitations

In the mean time, before the variations were finally committed entirely to writing, the Quran was preserved by recitation and recitations of the Quran were passed down from one or more prominent reciters of a style of narration who had memorized the Quran (known as hafiz) to the next generation. According to Okvath Csaba,

It was during the period of the Successors [the generation of Muslims after the companions] and shortly thereafter that exceptional reciters became renowned as teachers of Qur'anic recitation in cities like Makkah, Madina, Kufa, Basra, and greater Syria (al-Sham). They attracted students from all over the expanding Muslim state and their modes of recitations were then attached to their names. It is therefore commonly said that he recites according to the reading of Ibn Kathir or Nafic; this, however, does not mean that these reciters are the originators of these recitations, their names have been attached to the mode of recitation simply because their rendition of the Prophetic manner of recitation was acclaimed for authenticity and accuracy and their names became synonymous with these Qur'anic recitations. In fact, their own recitation goes back to the Prophetic mode of recitation through an unbroken chain.[15]

Each reciter had variations in their tajwid rules and occasional words in their recitation of the Qur'an are different or of a different morphology (form of the word) with the same root. The different words compliment other recitations and add to the meaning, and are a source of exegesis.[16] Aisha Abdurrahman Bewley gives an example of a line of transmission line "you are likely to find ... in the back of a Qur'an" from the Warsh harf, going backwards from Warsh to Allah: "'the riwaya of Imam Warsh from Nafi' al-Madini from Abu Ja'far Yazid ibn al-Qa'qa' from 'Abdullah ibn 'Abbas from Ubayy ibn Ka'b from the Messenger of Allah, may Allah bless him and grant him peace, from Jibril, peace be upon him, from the Creator.'"[16]

The ten Qari of the recitations lived in the second and third century of Islam. (Their death dates span from 118 AH to 229 AH). The seven qira'at readings which are currently notable were selected in the forth century by Abu Bakr Ibn Mujahid (died 324 AH, 936 CE) from prominent reciters of his time, three from Kufa and one each from Mecca, Medina, and Basra and Damascus.[17]

Each reciter recited to two narrators whose narrations are known as riwaya (transmissions) and named after its primary narrator (rawi, singular of riwaya). Each rawi has turuq (transmission lines) with more variants created by notable students of the master who recited them and named after the student of the master. Passed down from Turuq are wujuh: the wajh of so-and-so from the tariq of so-and-so. There are about twenty riwayat and eighty turuq.[3]

In the 1730s, Quran translator George Sale noted seven principal editions of the Quran, "two of which were published and used at Medina, a third at Mecca, a fourth at Cufa, a fifth at Basra, a sixth in Syria, and a seventh called the common or vulgar edition." He states that "the chief disagreement between their several editions of the Koran, consists in the division and number of the verses."[18]

Reciting

Abu Ubaid al-Qasim bin Salam (774 - 838 CE) was the first to develop a recorded science for tajwid (a set of rules for the correct pronunciation of the letters with all their qualities and applying the various traditional methods of recitation), giving the rules of tajwid names and putting it into writing in his book called al-Qiraat. He wrote about 25 reciters, including the 7 mutawatir reciters.[19] He made the reality, transmitted through reciters of every generation, a science with defined rules, terms, and enunciation.[20][21]

Abu Bakr Ibn Mujāhid (859 - 936 CE) wrote a book called Kitab al-Sab’ fil-qirā’āt. He is the first to limit the number of reciters to the seven known. Some scholars, such as Ibn al-Jazari, took this list of seven from Ibn Mujahid and added three other reciters (Abu Ja’far from Madinah, Ya’qub from Basrah, and Khalaf from Kufa) to form the canonical list of ten.[19][22]

Imam Al-Shatibi (1320 - 1388 CE) wrote a poem outlining the two most famous ways passed down from each of seven strong imams, known as ash-Shatibiyyah. In it, he documented the rules of recitation of Naafi’, Ibn Katheer, Abu ‘Amr, Ibn ‘Aamir, ‘Aasim, al-Kisaa’i, and Hamzah. It is 1173 lines long and a major reference for the seven qira’aat.[23]

Ibn al-Jazari (1350 - 1429 CE) wrote two large poems about Qira'at and tajwid. One was Durrat Al-Maa'nia (Arabic: الدرة المعنية) , in the readings of three major reciters, added to the seven in the Shatibiyyah, making it ten. The other is Tayyibat An-Nashr (Arabic: طيبة النشر), which is 1014 lines on the ten major reciters in great detail, of which he also wrote a commentary.

Variations among readings

Examples of differences between readings

Most of the differences between the various readings involve consonant/diacritical marks (I‘jām) and vowels marks (Ḥarakāt), but not in the rasm or "skeleton" of the writing. The examples below show differences between the Hafs Qari and two others—Al-Duri and Warsh. All have differences in the consonantal/diacritical marking (and vowel markings), but only one has a difference in the rasm: "then it is what" v. "it is what", where a "fa" consonant letter is added to the verse.

- Al-Duri and Ḥafs

| Ḥafs | Al-Duri | Ḥafs | Al-Duri | verse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| وَيُكَفِّرُ | وَنُكَفِّرُ | and He will remove | and We will remove | Al-Baqara 2:271 (2:270 in Al-Duri) |

The "He" in Hafs is referring to God and the "We" in Al-Duri is also referring to God, this is due to the fact that God refers to Himself in both the singular form and plural form by using the royal "We".

- Ḥafs and Warsh

| رواية ورش عن نافع | رواية حفص عن عاصم | Ḥafs | Warsh | verse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| يَعْمَلُونَ | تَعْمَلُونَ | you do | they do | Al-Baqara 2:85 |

| مَا تَنَزَّلُ | مَا نُنَزِّلُ | We do not send down... | they do not come down... | Al-Ḥijr 15:8 |

| قُل | قَالَ | he said | Say! | Al-Anbiyā' 21:4 |

| كَثِيرًا | كَبِيرًا | mighty | multitudinous | Al-Aḥzāb 33:68 |

| بِمَا | فَبِمَا | then it is what | it is what | Al-Shura 42:30 |

| نُدْخِلْهُ | يُدْخِلْهُ | He makes him enter | We make him enter | Al-Fatḥ 48:17[24][25] |

Note the first difference in plurality in the first row, the "you" in Hafs refers to the actions of more than one person and the "They" in Warsh is also referring to the actions of more than one person. In the 2nd row "We" refers to God in Hafs and the "They" in Warsh refers to what is not being sent down by God (The Angels). In the last verse the "He" in Hafs is referring to God and the "We" in Warsh is also referring to God, this is due to the fact that God refers to Himself in both the singular form and plural form by using the royal "We".

The ten readers and their transmitters

According to Aisha Abdurrahman Bewley and Quran eLearning, the seven qira’a are mutawatir ("a transmission which has independent chains of authorities so wide as to rule out the possibility of any error and on which there is consensus"), and the three are Mashhur ("these are slightly less wide in their transmission, but still so wide as to make error highly unlikely").[3][26] In addition to the ten "recognized" or "canonical modes"[27] of qira’at, there are four other modes of recitation – Ibn Muhaysin, al-Yazeedi, al-Hasan and al-A‘mash -- but at least according to one source (the Saudi Salafi site "Islam Question and Answer"), these last four recitations are "odd" (shaadhdh) -- in the judgement of "the correct, favoured view, which is what we learned from most of our shaykhs" -- and so are not recognized.[2]

| Qari (reader) | Rawi (transmitter) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Born | Died | Full name | Details | Name | Born | Died | Full name | Details | Current region |

| Nafi‘ al-Madani | 70 AH | 169 AH (785 CE)[6] | Ibn 'Abd ar-Rahman Ibn Abi Na'im, Abu Ruwaym al-Laythi | Persian with roots from Isfahan. Is commonly confused with Nafi' the mawla of Ibn Umar. | Qalun | 120 AH | 220 AH (835 CE)[6] | Abu Musa, 'Isa Ibn Mina al-Zarqi | Client of Bani Zuhrah | Libya, Tunisia, and parts of Al-Andalus and Qatar |

| Warsh | 110 AH | 197 AH (812 CE)[6] | 'Uthman Ibn Sa'id al-Qutbi | Egyptian; client of Quraysh | Al-Andalus, Algeria, Morocco, parts of Tunisia, West Africa and Sudan, and parts of Libya | |||||

| Ibn Kathir al-Makki | 45 AH | 120 AH (738 CE)[6] | 'Abdullah, Abu Ma'bad al-'Attar al-Dari | Persian | Al-Bazzi | 170 AH | 250 AH (864 CE)[6] | Ahmad Ibn Muhammad Ibn 'Abdillah, Abu al-Hasan al-Buzzi | Persian | |

| Qunbul | 195 AH | 291 AH (904 CE)[6] | Muhammad Ibn 'Abd ar-Rahman, al-Makhzumi, Abu 'Amr | Meccan and Makhzumi (by loyalty) | ||||||

| Abu 'Amr Ibn al-'Ala' | 68 AH | 154 AH (770 CE)[6] | Zuban Ibn al-'Ala' at-Tamimi al-Mazini, al-Basri | Al-Duri | 150 AH | 246 AH (860 CE)[6] | Abu 'Amr, Hafs Ibn 'Umar Ibn 'Abd al-'Aziz al-Baghdadi | Grammarian, blind | Parts of Sudan and West Africa | |

| Al-Susi | ? | 261 AH (874 CE)[6] | Abu Shu'ayb, Salih Ibn Ziyad Ibn 'Abdillah Ibn Isma'il Ibn al-Jarud ar-Riqqi | |||||||

| Ibn Amir ad-Dimashqi | 8 AH | 118 AH (736 CE)[6] | 'Abdullah Ibn 'Amir Ibn Yazid Ibn Tamim Ibn Rabi'ah al-Yahsibi | Hisham | 153 AH | 245 AH (859 CE)[6] | Abu al-Walid, Hisham ibn 'Ammar Ibn Nusayr Ibn Maysarah al-Salami al-Dimashqi | Parts of Yemen | ||

| Ibn Dhakwan | 173 AH | 242 AH (856 CE)[6] | Abu 'Amr, 'Abdullah Ibn Ahmad al-Qurayshi al-Dimashqi | |||||||

| Aasim ibn Abi al-Najud | ? | 127 AH (745 CE)[6] | Abu Bakr, 'Aasim Ibn Abi al-Najud al-'Asadi | Persian ('Asadi by loyalty) | Shu'bah | 95 AH | 193 AH (809 CE)[6] | Abu Bakr, Shu'bah Ibn 'Ayyash Ibn Salim al-Kufi an-Nahshali | Nahshali (by loyalty) | |

| Hafs | 90 AH | 180 AH (796 CE)[6] | Abu 'Amr, Hafs Ibn Sulayman Ibn al-Mughirah Ibn Abi Dawud al-Asadi al-Kufi | Muslim world generally | ||||||

| Hamzah az-Zaiyyat | 80 AH | 156 AH (773 CE)[6] | Abu 'Imarah, Hamzah Ibn Habib al-Zayyat al-Taymi | Persian (Taymi by loyalty) | Khalaf | 150 AH | 229 AH (844 CE)[6] | Abu Muhammad al-Asadi al-Bazzar al-Baghdadi | ||

| Khallad | ? | 220 AH (835 CE)[6] | Abu 'Isa, Khallad Ibn Khalid al-Baghdadi | Quraishi | ||||||

| Al-Kisa'i | 119 AH | 189 AH (804 CE)[6] | Abu al-Hasan, 'Ali Ibn Hamzah al-Asadi | Persian (Asadi by loyalty) | Al-Layth | ? | 240 AH (854 CE)[6] | Abu al-Harith, al-Layth Ibn Khalid al-Baghdadi | ||

| Al-Duri | ? | 246 AH (860 CE) | Abu 'Amr, Hafs Ibn 'Umar Ibn 'Abd al-'Aziz al-Baghdadi | Transmitter of Abu 'Amr (see above) | ||||||

The three Mashhur Qiraat are:

| Qari (reader) | Rawi (transmitter) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Born | Died | Full name | Details | Name | Born | Died | Full name | Details |

| Abu Ja'far | ? | 130 AH | Yazid Ibn al-Qa'qa' al-Makhzumi al-Madani | 'Isa Ibn Wardan | ? | 160 AH | Abu al-Harith al-Madani | Madani by style | |

| Ibn Jummaz | ? | 170 AH | Abu ar-Rabi', Sulayman Ibn Muslim Ibn Jummaz al-Madani | ||||||

| Ya'qub al-Yamani | 117 AH | 205 AH | Abu Muhammad, Ya'qub Ibn Ishaq Ibn Zayd Ibn 'Abdillah Ibn Abi Ishaq al-Hadrami al-Basri | Client of the Hadramis | Ruways | ? | 238 AH | Abu 'Abdillah, Muhammad Ibn al-Mutawakkil al-Basri | |

| Rawh | ? | 234 AH | Abu al-Hasan, Rawh Ibn 'Abd al-Mu'min, al-Basri al-Hudhali | Hudhali by loyalty | |||||

| Khalaf | 150 AH | 229 AH | Abu Muhammad al-Asadi al-Bazzar al-Baghdadi | Transmitter of Hamza (see above) | Ishaq | ? | 286 AH | Abu Ya'qub, Ishaq Ibn Ibrahim Ibn 'Uthman al-Maruzi al-Baghdadi | |

| Idris | 189 AH | 292 AH | Abu al-Hasan, Idris Ibn 'Abd al-Karim al-Haddad al-Baghdadi | ||||||

Popularity of Hafs ‘an ‘Asim

One qira'a that has reached overwhelming popularity is the Hafs ‘an ‘Asim, specifically the standard Egyptian edition of the Qur’an first published on July 10, 1924 in Cairo. Its publication has been called a "terrific success", and the edition has been described as one "now widely seen as the official text of the Qur’an", so popular among both Sunni and Shi'a that the common belief among less well-informed Muslims is "that the Qur’an has a single, unambiguous reading", namely the 1924 Cairo version.[28] Another source states that "for all practical purposes", it is the one Quranic version in "general use" in the Muslim world today.[10][Note 6]

Among the reasons given for the overwhelming popularity of Hafs an Asim is that it is easy to recite and that Allah has chosen it to be widespread (Qatari Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs).[31] Ingrid Mattson credits mass-produced printing press mushaf with increasing the availability of the written Quran, but also with making one version widespread (not specifically Hafs 'an 'Asim) at the expense of diversity of qira'at.[32]

Gabriel Said Reynolds emphasizes that the goal of the Egyptian government in publishing the edition was not to delegitimize the other qira’at, but to eliminate variations found in Qur’anic texts used in state schools, and to do this they chose to preserve one of the fourteen qira’at “readings”, namely that of Hafs (d. 180/796) ‘an ‘Asim (d. 127/745).

Criteria for Categorization

All accepted qira'at follow three basic rules:

- Conformity to the consonantal skeleton of the Uthmānic codex.

- Consistency with Arabic grammar.

- Authentic chain of transmission.

The qira'at that do not meet these conditions are called shaadh (anomalous/irregular). The other recitations reported from companions that differ from the Uthmānic codex may represent an abrogated or abandoned ḥarf, or a recitation containing word alterations for commentary or for facilitation for a learner. It is not permissible to recite the shaadh narrations in prayer, but they can be studied academically.[22]

Qira'at and Ahruf

Difference between them

Although both Qira'at (recitations) and Ahruf (styles) refer to variants of the Quran, they are not the same. Ahruf variants were more significant (involving differences in the consonants of some words of the Quran) and Caliph 'Uthman is believed to have eliminated all but one,[13] so that the different qira'at come from just one of the seven Ahruf of the Quran.[4] The seven qira'at readings which are currently notable were selected by Abu Bakr Ibn Mujahid (died 324 AH, 936 CE) from prominent reciters of his time, three from Kufa and one each from Mecca, Medina, and Basra and Damascus.[17] IslamQA website notes that while both mention seven in number, the seven in the seven qira’at (al-qiraa’aat al-saba’) comes not from the Qur’an or Sunnah but from the "ijtihaad [[independent reasoning] of Ibn Mujaahid", who may have been tempted to arrive at that number by the fact that were seven ahruf.[4]

Bilal Philips writes that the Quran continued to be read according to the seven ahruf until midway through Caliph 'Uthman's rule, when confusion developed in the outlying provinces about the Quran's recitation. Some Arab tribes boasted about the superiority of their ahruf, and rivalries began; new Muslims also began combining the forms of recitation out of ignorance. Caliph 'Uthman decided to make official copies of the Quran according to the writing conventions of the Quraysh and send them with the Quranic reciters to the Islamic centres. His decision was approved by Sahaabah, and all unofficial copies of the Quran were ordered destroyed; Uthman carried out the order, distributing official copies and destroying unofficial copies, so that the Quran began to be read in one harf, the same one in which it is written and recited throughout world today.[5]

Philips writes that Qira'at is primarily a method of pronunciation used in recitations of the Quran. These methods are different from the seven forms, or modes (ahruf), in which the Quran was revealed. The methods have been traced back to Muhammad through a number of Sahaabah (companions) who were noted for their Quranic recitations; they recited the Quran to Muhammad (or in his presence), and received his approval. The Sahaabah included:

- Ubayy ibn Ka'b

- Ali Ibn Abi Talib

- Zayd ibn Thabit

- Abdullah ibn Masud

- Abu Darda

- Abu Musa al-Ash'ari

Many of the other Sahaabah learned from them; master Quran commentator Ibn 'Abbaas learned from Ubayy and Zayd.[33]

According to Philips, in the next generation of Muslims (referred to as Tabi'in) were many scholars who learned the methods of recitation from the Sahaabah and taught them to others. Centres of Quranic recitation developed in al-Madeenah, Makkah, Kufa, Basrah and Syria, leading to the development of Quranic recitation as a science. By the mid-eighth century CE, a large number of scholars were considered specialists in the field of recitation. Most of their methods were authenticated by chains of reliable narrators, going back to Muhammad. The methods which were supported by a large number of reliable narrators on each level of their chain were called mutawaatir, and were considered the most accurate. Methods in which the number of narrators were few (or only one) on any level of the chain were known as shaadhdh. Some scholars of the following period began the practice of designating a set number of individual scholars from the previous period as the most noteworthy and accurate. The number seven became popular by the mid-10th century, since it coincided with the number of dialects in which the Quran was revealed.[34]

Javed Ahmad Ghamidi writes about hadith in Muwatta[7] that if Ahruf are taken in the context of pronunciation (for which the words are lughat and lahjat), the content of the hadith rejects this meaning; Umar and Hisham belonged to the same tribe (the Quraysh), and members of the same tribe cannot use different pronunciations. Ghamidi questions the hadith which claim "variant readings", on the basis of Quranic verses ([Quran 87:6-7], [Quran 75:16-19]), the Quran was compiled during Muhammad's lifetime and questions the hadith which report its compilation during Uthman's reign.[35] Since most of these narrations are reported by Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri, Imam Layth Ibn Sa'd wrote to Imam Malik:[35][36]

And when we would meet Ibn Shihab, there would arise a difference of opinion in many issues. When any one of us would ask him in writing about some issue, he, in spite of being so learned, would give three very different answers, and he would not even be aware of what he had already said. It is because of this that I have left him – something which you did not like.

Abu 'Ubayd Qasim Ibn Sallam (died 224 AH) reportedly selected twenty-five readings in his book. The seven readings which are currently notable were selected by Abu Bakr Ibn Mujahid (died 324 AH, 936 CE) at the end of the third century. It is generally accepted that although their number cannot be ascertained, every reading is Quran which has been reported through a chain of narration and is linguistically correct. Some readings are regarded as mutawatir, but their chains of narration indicate that they are ahad (isolate) and their narrators are suspect in the eyes of rijal authorities.[35]

Scriptural basis for seven Ahruf

- Hadith

According to Bismika Allahuma, "the Qur’aan was revealed in seven ahruf." The proof for this is found in many hadith, "so much so that it reaches the level of mutawaatir." One scholar, Jalaal ad-Deen as-Suyootee, claims that twenty-one traditions of Companions of the Prophet state "that the Qur’aan was revealed in seven ahruf".[37]

Hadith literature differs on variants of the Quran. According to some hadith, the Quran was revealed in seven Ahruf (the plural of harf) or styles; Muhammad listens to their recitations and approves each of them. According to Saalih al-Munajjid, "the best of the scholarly opinions" defining Ahruf is wording which differs but has the same meaning.[4] The best-known hadith on Ahruf is reported in the Muwatta, compiled by Malik ibn Anas. According to Malik,[7]

Abd Al-Rahman Ibn Abd al-Qari narrated: "Umar Ibn al-Khattab said before me: I heard Hisham Ibn Hakim Ibn Hizam reading Surat Al-Furqan in a different way from the one I used to read it, and the Prophet himself had read out this surah to me. Consequently, as soon as I heard him, I wanted to get hold of him. However, I gave him respite until he had finished the prayer. Then I got hold of his cloak and dragged him to the Prophet. I said to him: "I have heard this person [Hisham Ibn Hakim Ibn Hizam] reading Surah Al Furqan in a different way from the one you had read it out to me." The Prophet said: "Leave him alone [O 'Umar]." Then he said to Hisham: "Read [it]." [Umar said:] "He read it out in the same way as he had done before me." [At this,] the Prophet said: "It was revealed thus." Then the Prophet asked me to read it out. So I read it out. [At this], he said: "It was revealed thus; this Quran has been revealed in seven Ahruf. You can read it in any of them you find easy from among them.

Rationale

According to Oliver Leaman, "the origin" of the differences of qira'at "lies in the fact that the linguistic system of the Quran incorporates the most familiar Arabic dialects and vernacular forms in use at the time of the Revelation."[1] According to Okvath Csaba, "Different recitations [different qira'at] take into account dialectal features of Arabic language ..." [15]

Aisha Abdurrahman Bewley writes that "the different words" in the different Qiraat "compliment other recitations and add to the meaning, and are a source of exegesis."[16] Ammar Khatib and Nazir Khan contend that "in certain cases" the differences in qirāʾāt "add nuances in meaning, complementing one another."[27]

Oxford Islamic Studies Online writes that "according to classical Muslim sources", the variations that crept up before Uthman created the "official" Quran "dealt with subtleties of pronunciations and accents (qirāʿāt) and not with the text itself which was transmitted and preserved in a culture with a strong oral tradition."[38]

Questions

Other reports of what the Prophet said (as well as some scholarly commentary) seem to contradict the presence of variant readings -- ahruf or qirāʾāt.[35]

Abu Abd Al-Rahman al-Sulami writes, "The reading of Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Zayd ibn Thabit and that of all the Muhajirun and the Ansar was the same. They would read the Quran according to the Qira'at al-'ammah. This is the same reading which was read out twice by the Prophet to Gabriel in the year of his death. Zayd ibn Thabit was also present in this reading [called] the 'Ardah-i akhirah. It was this very reading that he taught the Quran to people till his death".[39] According to Ibn Sirin, "The reading on which the Quran was read out to the prophet in the year of his death is the same according to which people are reading the Quran today".[40]

Examining the hadith of Umar's surprise in finding out "this Quran has been revealed in seven Ahruf", Suyuti, a noted 15th-century Islamic theologian, concludes the "best opinion" of this hadith is that it is "mutashabihat", i.e. its meaning "cannot be understood."[41]

Doubts

Codification time controversy

Non-Muslim Islamic scholar Fred Donner argues (as of 2008) that the large number of qira'at stemming from early "regional traditions" of Medina, Kufa, Basra, Syria, etc.; with variations in the rasm (usually consonants) "as well" vowelling,[42] suggests evidence not for qira'at being slight deviations from an original text developing over time from in the different pronunciation of different dialects; but for their being different Qurans that had not yet "crystalized into a single, immutable codified form ... within one generation of Muhammad".[42] Donner argues that there is evidence for both the hypotheses that the Quran was codified earlier than the standard narrative and for codification later.[42]

But Donner does agree with the standard narrative that despite the presence of "some significant variants" in the qira'at literature, there are not "long passages of otherwise wholly unknown text claiming to be Quran, or that appear to be used as Quran -- only variations within a text that is clearly recognizable as a version of a known Quranic passage".[43] Revisionist historian Michael Cook also states that the Quran "as we know it", is "remarkably uniform" in the rasm.[44]

See also

- Qari

- Tajweed

- Ibn al-Jazari

- Bible study (Christian)

- Khutbah

- Pani patti

- Saad El Ghamidi

- Sermon, in Christianity

- Torah reading and cantillation in Judaism

References

- Habib Hassan Touma (1996). The Music of the Arabs, trans. Laurie Schwartz. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-88-8.

Notes

- According to one source (the Saudi Salafi site "Islam Question and Answer"), while there are four other modes of recitation in addition to the ten recognized ones, these are "odd (shaadhdh), according to scholarly consensus":

"The seven modes of recitation are mutawaatir according to consensus, as are the three others: the recitations of Abu Ja‘far, Ya‘qoob and Khalaf, according to the more correct view. In fact the correct, favoured view, which is what we learned from most of our shaykhs, is that the recitations of the other four – Ibn Muhaysin, al-Yazeedi, al-Hasan and al-A‘mash, are odd (shaadhdh), according to scholarly consensus."

The article then goes on to quote the medieval scholar An-Nawawi saying:

" it is not permissible to recite, in prayer or otherwise, according to an odd mode of recitation, because that is not Qur’an."

The article separates the ten qira'at into "the seven": "The seven modes of recitation are mutawaatir according to the four imams and other leading Sunni scholars";

and "the three others" which are also mutawaatir, though apparently not having the same level of endorsement.[2] - for example, in Surat al-Baqara (1): "Dhalika'l-Kitabu la rayb" or "Dhalika'l-Kitabu la rayba fih" [3]

- an example being "suddan" or "saddan"[3]

- (due to different diacritical marks, for example, ya or ta (turja'una or yurja'una) or a word having a long consonant or not (a consonant will have a shadda making it long, or not have one).[3]

- For example "fa-tabayyanu" or "fa-tathabbatu" in Q4.94[9]

- Some other versions with minor divergences, namely those of Warsh (d.197/812) ....circulate in the northwestern regions of African.[29][30]

Citations

- Kahteran, Nevad (2006). "Hafiz/Tahfiz/Hifz/Muhaffiz". In Leaman, Oliver (ed.). The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 233. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- "The seven modes of recitation are mutawaatir and it is not permissible to cast aspersions on them. Question 178120". Islam Question and Answer. 24 November 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- The Seven Qira'at of the Qur'an by Aisha Bewley

- "The revelation of the Qur'aan in seven styles (ahruf, sing. harf). Question 5142". Islam Question and Answer. 28 July 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Abu Ameenah Bilal Philips, Tafseer Soorah Al-Hujuraat, 1990, Tawheed Publications, Riyadh, pp. 28-29.

- Shady Hekmat Nasser, Ibn Mujahid and the Canonization of the Seven Readings, p. 129. Taken from The Transmission of the Variant Readings of the Qur'an: The Problem of Tawaatur and the Emergence of Shawaadhdh. Leiden: Brill Publishers, 2012. ISBN 9789004240810

- Malik Ibn Anas, Muwatta, vol. 1 (Egypt: Dar Ahya al-Turath, n.d.), p. 201, (no. 473).

- narrated by al-Bukhari (Sahih al-Bukhari), 3047; Muslim Sahih Muslim, p. 819.

- Younes, Munther (2019). Charging Steeds or Maidens Performing Good Deeds: In Search of the Original Qur'an. Routledge. p. 3. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Böwering, "Recent Research on the Construction of the Quran", 2008: p.74

- "Lawh Mahfuz". Oxford Islamic Studies. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Cook, The Koran, 2000: pp. 72-73.

- Donner, "Quran in Recent Scholarship", 2008: pp. 35-36.

- Bursi, Adam (2018). "Connecting the Dots: Diacritics Scribal Culture, and the Quran". Journal of the International Qur'anic Studies Association. 3: 111. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- Csaba, Okvath (Winter 2014). "Ibn Mujahid and Canonical Recitations". Islamic Sciences. 12 (2). Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Bewley, Aisha. "The Seven Qira'at of the Qur'an". International Islamic University of Malaysia. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Cook, The Koran, 2000: p. 73

- Sale, George (1891). "Preliminary Discourse, section 3,". The Koran, Commonly Called the Alkoran of Mohammed. Frederick Warne and Co. p. 45.

- Ajaja, Abdurrazzak. "القراءات : The readings".

- el-Masry, Shadee. The Science of Tajwid. Safina Society. p. 8. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "What is Tajweed?". Online Quran Teachers. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Khan, Nazir; Khatib, Ammar. "The Origins of the Variant Readings of the Qur'an". Yaqeen Institute. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "Ijazah in Ash-Shatibiyyah". Online Quran Teachers.

- رواية ورش عن نافع - دار المعرفة - دمشق Warsh Reading, Dar Al Maarifah Damascus

- رواية حفص عن عاصم - مجمع الملك فهد - المدينة Ḥafs Reading, King Fahd Complex Madinah

- "Qiraat". Quran eLearning. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Khatib, Ammar; Khan, Nazir (23 August 2019). "Variant Readings of the Qur'an". Yaqueen Institute. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Reynolds, "Quranic studies and its controversies", 2008: p. 2

- QA. Welch, Kuran, EI2 5, 409

- Böwering, "Recent Research on the Construction of the Quran", 2008: p.84

- "Popularity of the recitation of Hafs from 'Aasim. Fatwa No: 118960". Islamweb. 9 March 2009. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Mattson, Ingrid (2013). The Story of the Qur'an: Its History and Place in Muslim Life. John Wiley & Sons. p. 129. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Abu Ameenah Bilal Philips, Tafseer Soorah Al-Hujuraat, 1990, Tawheed Publications, Riyadh, pp. 29–30.

- Abu Ameenah Bilal Philips, Tafseer Soorah Al-Hujuraat, 1990, Tawheed Publications, Riyadh, pp. 30.

- Javed Ahmad Ghamidi. Mizan, Principles of Understanding the Qu'ran Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Al-Mawrid

- Ibn Qayyim, I'lam al-Muwaqqi'in, vol. 3 (Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, n.d.), p. 96.

- BISMIKA ALLAHUMA TEAM (9 October 2005). "The Ahruf Of The Qur'aan". BISMIKA ALLAHUMA Muslim Responses to Anti-Islam Polemics. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Qurʿān". Oxford Islamic Studies. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Zarkashi, al-Burhan fi Ulum al-Qur'an, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Beirut: Dar al-Fikr, 1980), p. 237.

- Suyuti, al-Itqan fi Ulum al-Qur'an, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (Baydar: Manshurat al-Radi, 1343 AH), p. 177.

- Suyuti, Tanwir al-Hawalik, 2nd ed. (Beirut: Dar al-Jayl, 1993), p. 199.

- Donner, "Quran in Recent Scholarship", 2008: p.42

- Donner, "Quran in Recent Scholarship", 2008: p.42-3

- Cook, The Koran, 2000: p.119

Sources

- Qiraa'aat Warch & Hafs

- Islamic-Awareness.org

- The seven Qira'at

- cAlawi Ibn Muhammad Ibn Ahmad Bilfaqih, Al-Qirâ'ât al-cashr al-Mutawâtir, 1994, Dâr al-Muhâjir

- Adrian Brockett, "The Value of Hafs And Warsh Transmissions For The Textual History Of The Qur'an" in Andrew Rippin's (Ed.), Approaches of The History of Interpretation of The Qur'an, 1988, Clarendon Press, Oxford, p. 33.

- Samuel Green, " The different Arabic versions of the Quran Part 2: the current situation

- Böwering, Gerhard (2008). "Recent Research on the Construction of the Quran". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context. Routledge.

- Reynolds, Gabriel Said (2008). "Introduction, Quranic studies and its controversies". In Reynolds, Gabriel Said (ed.). The Quran in its Historical Context (PDF). Routledge. pp. 1–26.

- Cook, Michael (2000). The Koran : A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192853449.

The Koran : A Very Short Introduction.

Further reading

- Motivation and interest in reading engagement

- Gade, Anna M. Perfection Makes Practice: Learning, Emotion, and the Recited Qur'ân in Indonesia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004.

External links

- The Origins of the Variant Readings of the Qur’an, Yaqeen Institute

- Online Quran Project Community Site.

- Frequent Questions around qiraat about: the different Qiraat, including REFUTING The Claim of Differences in Quran and other useful information