Thurlow House

Thurlow House is a heritage-listed residence at 9 Stuart Crescent, Blakehurst in the Georges River Council local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by Harry Seidler and built from 1953 to 1954. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 21 October 2016.[1]

| Thurlow House | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Heritage boundaries | |

| Location | 9 Stuart Crescent, Blakehurst, Georges River Council, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°59′56″S 151°06′23″E |

| Built | 1953–1954 |

| Architect | Harry Seidler |

| Official name: Thurlow House | |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Designated | 21 October 2016 |

| Reference no. | 1980 |

| Type | House |

| Category | Residential buildings (private) |

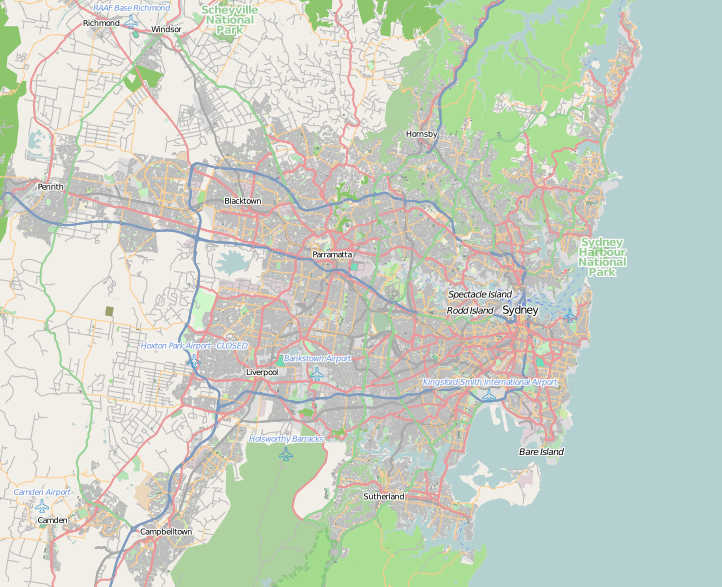

Location of Thurlow House in Sydney | |

History

The site of 9 Stuart Crescent is part of 36 hectares (88 acres) (Portion 250 of the Parish of St George) granted to merchant and brewer John Terry Hughes, the nephew of wealthy emancipated convict merchant Samuel Terry, and his business partner John Hosking, who was also the second mayor of Sydney. They were granted the land on 26 August 1840.[1]

In April 1853 the president of the Bank of New South Wales, John Holden, conveyed the property to Benjamin Yabsley, who the following day conveyed it to Charles Mitchell. After Mitchell died the trustees of his estate sold the property to George Alfred Tucker, in March 1874. Three years later Tucker sold the land to Samuel William Gray, who made application to convert the property to Torrens Title in December 1881.[1]

Gray (1823–1889) was born in Armagh in Northern Ireland. He and his family arrived in NSW around 1835. His father purchased 520 hectares (1,280 acres), known as "Omega Retreat", between Kiama and Gerringong and became a farmer and grazier. Gray was educated at the Normal Institution in Sydney, following which he went to sea in 1849 and then travelled to Bendigo during the gold rushes. He returned to Kiama and settled into life as a farmer and grazier at Bendella. Gray leased 1,600 hectares (3,950 acres) in the Camden District in 1860 and in the early 1860s took up land on the Tweed River. He later returned to family properties near Kiama. He became a Member of the Legislative Assembly in June 1859, initially representing Kiama and subsequently Illawarra and Richmond. Gray acquired business interests in Sydney and lived there until his death.[1]

After Gray died the land passed to his widow Mary, police magistrate Joshua Bray of Murwillumbah and Edmund Caswell Bowyer Smyth, engineer of Albury. It was bounded by a foreshore reservation, which, was subsequently granted to Mrs Gray, Bray and Edmund Caswell Bowyer-Smyth on 17 May 1894. The land was then assigned to Augustus Morris and Charles King in October 1894, who later that month transferred its title to the City Bank of Sydney. On 18 August 1911 the title to 3 roods 7 perches of the land was transferred to master plumber William Henry Watson of St Peters, who in turn transferred it to plumber Francis Watson of Blakehurst on 28 October 1919. Francis Watson sold the land to Percy Allan, licensee of the Pymble Hotel, during the first quarter of 1929. Allan subdivided it into three allotments and offered it for sale at the beginning of the 1940s. The first sale was to Marrickville bricklayer Thomas Tyson Dixon and his wife Ellen. Transfer of title took place on 26 May 1941. The Dixons sold the land to Ryde electrician John McBride in February 1944. McBride then sold it to master mariner William Obide Lewis Wilding and his wife Agnes, who lived in Hurstville, in July 1946. They, in turn, sold the land to master tanner James Thomas Dale of Maroubra in May 1949; he sold it to Bankstown company director Herbert George Palmer in July 1950. The following year Palmer sold the land to Mr and Mrs David Thurlow. The transfer of title took place on 17 September 1951, to Marjorie Olive Thurlow.[1]

Marjorie Thurlow, nee Latham, was born on 14 December 1919, the younger daughter of Mr and Mrs Bertrand Latham of Roseville. Her father was secretary to the Board of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia, subsequently serving as secretary of the Note Issuing Department and its Chief Actuary. She had two brothers and one sister, and attended Abbotsleigh School in Wahroonga. Marjorie Latham graduated from the University of Sydney with a Bachelor of Arts in English, European History and Psychology in 1940. Marjorie (also known as Dolly by family members) joined the RAAF in World War II and is thought to have served as an Assistant Section Officer in Signalling Corps. On 25 May 1946, Marjorie Latham married David Keith Thurlow at Roseville Methodist Church. David Thurlow was born on 25 November 1919, the son of Mr and Mrs W Thurlow of Pymble. He served articles under solicitors E Lewis and J Egan of Sydney and studied law at the University of Sydney during the first half of the 1940s. On 7 March 1947, he applied to be admitted as a solicitor of the Supreme Court of NSW and subsequently set up in practice. The firm that he founded continues today. The young couple initially lived at Punchbowl until moving to Blakehurst. They engaged the dynamic up-and-coming young architect Harry Seidler to design their new home there.[1]

Harry Seidler (1923–2006) was born in Vienna. He left there in 1938, moving to England to escape the Nazi occupation of Austria. He studied Building at the Cambridge Shire Technical School but was interned in 1940 and eventually shipped to Canada. In Canada, he was permitted to study architecture at the University of Manitoba. He graduated with first class honours in 1944 and the following year won a scholarship allowing him to attend the Harvard Graduate School of Design where he studied under architect Walter Gropius, formerly Director of the Bauhaus in Germany. Seidler then studied at the experimental and short-lived Black Mountain College summer school in 1946 under another former Bauhaus teacher, Josef Albers. Between September 1946 and March 1948 Seidler worked as architect Marcel Breuer's chief assistant. Breuer, who had been educated at the Bauhaus and then became master of its carpentry shop, had also been Gropius' professional partner during the 1930s. Seidler left America to travel to Australia, spending some time in Rio de Janeiro to work with the prominent architect Oscar Niemeyer. He finally arrived in Sydney during July 1948, having travelled all that distance at the instigation of his parents. They had migrated here from England in 1946 and had asked if he could design a house for them. The Rose Seidler House (named after his mother) was the very first that he built in Australia and was completed in 1950. It opened the door to numerous commissions for houses over the next five decades that were situated across metropolitan Sydney and its outskirts, in Canberra and as far away as Darwin. The house also won Seidler his first Sulman Medal.[1]

The firm of Harry Seidler & Associates was formed around 1954. Seidler approached Gerardus (Dick) Dusseldorp of the recently formed Lend Lease Corporation at the end of the 1950s with plans of what was to become the block of flats called Ithaca Gardens in Elizabeth Bay. The relationship between Harry Seidler & Associates and Lend Lease proved fruitful right up to the beginning of the 1990s. Over the years Seidler's office designed a wealth of different building types including individual houses, apartment blocks, office buildings, public buildings and industrial structures that remained true to Harry Seidler's deeply held Modernist convictions about what architecture should be. This rigorous and uncompromising approach, though not always understood or appreciated by the general public, resulted in an impressive record of masterful and often innovative works, the quality of which was frequently recognised by awards for excellence.[1]

Significant Sydney projects include Blues Point Tower (1961), Australia Square, which won both the Sulman Medal and the Institute of Architect's Civic Design Award for 1967, the MLC Centre (1978), which won the Sulman Medal for 1983 and Grosvenor Place (1988) which was awarded the Sulman Medal for 1991. Seidler's own complex of office and residential spaces at Milson's Point (built in several stages between 1973 and 1994) received the Sulman Medal for 1981 while the office extension and penthouse won the Institute's Interiors Award for 1991. Seidler's national and international contributions to architecture were reflected in the receipt of the Institute of Architects' Gold Medal in 1976 and then was recognised by it once more with a Special Jury Award for International Practice in 2000. He was made an Honorary Fellow of the American Institute of Architects, while the Royal Institute of British Architects awarded him its highest honour, the Royal Gold Medal, in 1996. He was elected a member of the Academie D'Architecture de France in 1982, awarded the Gold Medal of the City of Vienna in 1989 and then Austria's highest honour, the Cross of Honour for Arts and Sciences First Class, in 1995.[1]

Design and documentation for the Thurlow's new house was well underway by September 1951. It was prepared by Frank D'Arcy and Don Gazzard. Structural engineer Peter Miller was also involved on the project. As with a number of early houses by Seidler, the Thurlow house was evidently built to a tight budget and the Thurlows organised construction of the house themselves.[1]

The concept behind the house was described on a sketch drawing describing the rear of the building. Issues of privacy were taken into account, as was the primacy of the view over the Georges River. The optimal location on the site, however, was only 12.5 metres (41 ft) wide - "enough for living-dining + kitchen." In this part of the site it was not considered desirable to expose rooms to the street or to the east and west because of privacy and "sunprotection" respectively. A two-storey house was considered both dull and wasteful "with 9'-0" minimum ceilings."[1]

Instead, "Low level mezzanine solution gives all rooms a view and also produces a covered terrace as well as interesting flowing interior vertical space. Sun enters higher living space thru sunprotection [sic] louvres on North toward sun court." Placing the carport on the northern side of the house was an "obvious location" for the structure.[1]

Marjorie and David Thurlow separated and were divorced in 1970. Marjorie remained living in the house until advancing age forced her into alternative accommodation.[1]

David Thurlow died on 8 February 2014. Marjorie Thurlow died on 14 December 2014.[1]

Description

Thurlow House consists of a split level dwelling and a detached garage, which are linked by a short covered concrete bridge. The garage is to the north of the house facing Stuart Crescent, while the house is oriented towards a view overlooking the Cooks River to the south. Eastern and western sides of the house are blank, providing protection from the sun and privacy from adjoining properties.[1]

The house is entered at mid-level; its plan is more or less bisected by an open tread stair with tubular steel handrails, one flight leading down to living areas, the other leading up to sleeping accommodation. The lower level contains a living room with a robust stone fireplace. It is separated from the dining area by the fireplace, along with the stair and entry landing. Beyond the dining room is a narrow kitchen and laundry, which opens onto a drying court between the house and the garage. The living and dining areas access a wide deck overlooking the view; a lavatory, aligned with the stair, intrudes into the deck space.[1]

The sleeping level above contains two bedrooms, a study and bathroom. This level extends from the southern end of the lower level spaces and cantilevers over the deck. The internal spaces are unified by the raked ceiling that falls from the southern side of the bedrooms to the north side of living areas. Storage space is located to the north of the main bedroom.[1]

Thurlow House was described in Seidler's first promotional book, Houses, Interiors and Projects, which was published in 1954. It remains relevant because of the high level of integrity that the house has retained:[1]

"The water frontage site overlooking the George's River to the South, resulted in all rooms of the house looking out in that direction. The two levels are staggered to result in space relationships between them inside, with the upper bedroom level forming the roof over the continuous view side terrace of the living floor. The slope of the site placed the double carport on a higher level on the street side and led the suspended approach bridge to an intermediate entrance level. Short flights of steps lead from it down to the living areas and up to the bedrooms.

Complete glass walls on the south bring the view into every part of the house. Ample glazing on the North to admit winter warmth is protected against the summer sun by horizontal fixed louvres. Sandblasted obscure glass is used on this side for privacy, except for a clear glass vision strip at eye level.

The house is built on a continuous rock shelf. The south end of the structure reaches out over the edge of the rock and is therefore cantilevered to avoid foundations on the steeply sloping ground below the rock. The construction is of random rubble masonry and brick walls, steel beams, timber floors and light frame walls for the cantilevered upper level. The interior finishes expose all these materials, with the timber-framed walls lined with T & G Tallow wood boarding, natural finished.

... Colours and textures are warm throughout: Natural timber, sandstone, yellow and brown materials ... the freely spanning flights of the stair ... Stringers are out of 12" x 2" [timber] painted."

The structure of the house consists of 280-millimetre (11 in) brick/stone cavity walls, steel columns and beams, timber-framed floors and roof. External walls are constructed out of randomly coursed sandstone and pale "Chromatex" bricks manufactured by Punchbowl Brick and Pipe Co. while internal walls are constructed out of timber stud framing. Floors are constructed with oregon joists fixed to lugs welded onto steel beams. Floors and internal walls are lined with tongue and groove tallow wood boards. The roof was originally lined with 4-ply asbestos felt (a commonly used building material at this time) with white marble chip protective finish, insulated with aluminium sarking and Insulwool batts and flashed with copper. It has since been replaced by metal decking. Windows are framed in steel.[1]

Internal lighting was quite advanced for the period and still remains in place – recessed ceiling mounted down lights and fluorescent tubes in the kitchen, above the east wall of the living room and dining rooms. Fluorescent tubes are also located in a recess behind the built-in cabinet mounted on the north wall of the living room. Supplementary wall mounted fixtures augment the main lighting. The kitchen was originally comprehensively detailed and equipped to a standard above most houses of the period. Much of this remains, such as an exhaust fan, cupboard and servery joinery and fitments. The kitchen is linked to the main bedroom by a dumb waiter.[1]

Condition

As of 22 February 2016, the house was in relatively good condition, although in need of some maintenance. The landscape setting is overgrown and weed-infested.[1]

The house has retained a high level of integrity and has retained a substantial amount of original building fabric, fitments and joinery items in living areas, bedrooms and kitchen/laundry[1]

Modifications and dates

Modifications have been limited in extent. The original roofing has been replaced with metal decking, possibly as a result of the deterioration of the original roofing materials and possible water ingress. The openings to the carport have been enclosed to form a garage, chains to convey roof rainwater have been installed on the northern side of the house, new floor linings have been installed above original kitchen floor linings, some appliances have been removed or replaced in the kitchen and some bathroom fittings have been replaced.[1]

Heritage listing

Thurlow House is of state heritage significance because it is a fine and rare example of an exceptionally intact early Modern Movement house, designed by influential and internationally significant architect Harry Seidler. It is representative of the early houses of Harry Seidler and demonstrates his design philosophy, methodology, exploitation of structure and use of building materials. The house is important in Seidler's body of work because of its inventive split level configuration and architectural form resulting from the constraints of the site and its view potential. The resulting house displays sophisticated spatial relationships and functional planning.[1]

Thurlow House incorporates progressive domestic construction and planning, demonstrated by the use of steel to cantilever sections of the building and the open planning that integrates living and bedroom areas. The house also provides evidence of advanced residential technology from the first half of the 1950s, demonstrated by elements such as indirect lighting using concealed fluorescent tubes and the integration of music equipment in built-in joinery in the living room. Its significance is enhanced by its high levels of physical integrity.[1]

The garden and grounds are an important component of the setting. They include remnant indigenous vegetation, which was intentionally retained during the construction of the house and which was rare for development in the early 1950s. The landscape setting, demonstrates Harry Seidler's philosophy that the settings for his houses be naturalistic. The retention of the single sculptural eucalypt in the front yard is characteristic of an aesthetic employed by Seidler and other Modern Movement architects. Views from the house over the treetops to the Georges River are significant as an essential element of the design of the house in its landscape setting.[1]

Thurlow House was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 21 October 2016 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

Thurlow House is of state significance as an early house design by architect Harry Seidler, who produced an important body of work in NSW, other parts of Australia and internationally. Seidler's architecture is notable for its consistent and rigorous application of Modern Movement principles.[1]

Thurlow House reflects the impact of Seidler's seminal and early Rose Seidler House on sections of the wider community. Members of the professions amongst others were attracted to Seidler's work because of its design characteristics and because of publicity generated by the architect, in part because of his significant battles with local government over advanced architectural design and aesthetics. It is a remarkably intact house that has undergone little change since it was completed in 1954, and provides evidence of the dissemination of advanced Modern Movement architectural design in NSW after World War II.[1]

The garden and grounds of Thurlow House include remnant indigenous vegetation, which was intentionally retained during the construction of the house and demonstrates Seidler's preferred philosophy that the setting for his houses should be minimal in a horticultural sense. This was uncommon for development in the early 1950s.[1]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

Thurlow House is of state significance for its association with internationally significant architect Harry Seidler and it is a fine example of Seidler's modernist design methodology. Seidler was the only architect working in NSW who had trained and worked under influential architects associated with the Bauhaus and brought a thorough understanding of European modernist methodology and aesthetics to NSW.[1]

The house is important in Seidler's body of work because of its particular split level configuration, whereby entry to the house is at mid-level and bedrooms are located on what equates to a mezzanine above living areas. The cantilevering of the bedrooms over the deck of the living areas is also a unique response to the constraints imposed by the site and its available views.[1]

Marjorie and David Thurlow, although not historically prominent, are representative of the young professional social class who commissioned Seidler, demonstrating awareness of, and positive response to, advanced architectural design within sections of the general community.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

Thurlow House is of state significance as a finely designed and well-executed example of Modernist residential architecture. It is one of the finest and most intact houses that survives from the first half of the 1950s in NSW. The house demonstrates advanced planning and split level configuration, and demonstrates convincingly and well the characteristics of the Modern Movement residential architecture. The aesthetic value of the house is due in part to the exploitation of its structural system to provide dramatic spatial qualities and architectural form. It also provides evidence of advanced residential technology and amenity from this period, such as fluorescent and other lighting, kitchen design and surviving joinery, built in joinery items including the cabinet in the living room, which accommodated stereo equipment, and early passive sun control devices.[1]

The materials used in the house-stone, timber, brick, steel-framed windows-the built-in joinery and detailing are a consistent part of Seidler's architectural repertoire at this time and demonstrate his skill in exploiting their intrinsic textural qualities and colouring.[1]

The landscape setting, despite inadequate maintenance, demonstrates architect Harry Seidler's philosophy that the settings for his houses be naturalistic. Views from the house over the treetops to the Georges River are significant as an essential element of the design of the house in its landscape setting.[1]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Thurlow House is of state significance as a rare example of a highly intact post-World War II Modern Movement house in NSW, which demonstrates advanced domestic construction and planning techniques.[1]

Although a relatively large number of Seidler's early houses have survived, many are known to have been subjected to alterations and additions which in some cases have obscured their early design and character. Thurlow House is rare at a state level as an intact example of the early architectural work of Harry Seidler.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

Thurlow House is of state significance as a fine, representative example of post-World War II Modern Movement domestic architecture in NSW.[1]

The house is representative of the early domestic architecture of Harry Seidler. It demonstrates many of the characteristics of his residential design, including planning and organisation of spaces over several levels to exploit views and provide amenity for the occupants; built-in joinery units and general standard of detailing; and exploitation of structure to achieve open planning and spatial complexity. The representative qualities of the house are enhanced by its high levels of physical integrity.[1]

The landscape setting demonstrates Harry Seidler's philosophy that the settings for his houses be naturalistic. The single sculptural eucalypt in the front yard is representative of a landscaping aesthetic preferred by Seidler and other Modern Movement architects.[1]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thurlow House. |

- "Thurlow House". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01980. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

Bibliography

- HeriCon Consulting. Thurlow House, 9 Stuart Crescent, Blakehurst: Heritage Assessment Report for the Heritage Council of NSW.

Attribution

![]()