Alaska pollock

The Alaska pollock or walleye pollock (Gadus chalcogrammus) is a marine fish species of the cod genus Gadus and family Gadidae. It is a semi-pelagic schooling fish widely distributed in the North Pacific, with largest concentrations found in the eastern Bering Sea.[2]

| Alaska pollock | |

|---|---|

| |

_-_GRB.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Gadiformes |

| Family: | Gadidae |

| Genus: | Gadus |

| Species: | G. chalcogrammus |

| Binomial name | |

| Gadus chalcogrammus Pallas, 1814 | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

Name and differentiation

In 2014, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration revealed that the official scientific name for the fish was changed from Theragra chalcogramma back to its original taxon Gadus chalcogrammus, highlighting its close genetic relationship to the other species of the cod genus Gadus.[3] Alaska pollock was long put in its own genus, Theragra, and classified as Theragra chalcogramma, but more recent research has shown it is rather closely related to the Atlantic cod and should therefore be moved back to Gadus, where it was originally placed.[4][5] The change of the official scientific name was followed by a discussion to change the common name as well, to highlight the fish as a member of the cod genus.[3][6] The common names "Alaska pollock" and "walleye pollock", both used as trade names internationally, are considered misleading by scientific and trade experts, as the names do not reflect the scientific classification.[7][8][9] While belonging to the same family as the Atlantic pollock, the Alaska pollock is not a member of the genus Pollachius, but of the cod genus Gadus. Nevertheless, alternative trade names highlighting its placement in the cod genus, such as "snow cod",[10][11][12] "bigeye cod",[11] or direct deductions from the scientific names such as "copperline cod" (gadus meaning 'cod', Latin: chalco- from Greek: khalkós meaning 'copper', and Greek: grammí meaning 'line'[13]) or "lesser cod" (from the synonymous taxon Gadus minor) have yet to find widespread acceptance.[6] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration even states that "[the common name] might never change, as common names are separate from scientific names".[6]

In addition, Norwegian pollock (Theragra finnmarchica), a rare fish of Norwegian waters, is likely the same species as the Alaska pollock.[14]

Ecology

The speckled coloring of Alaska pollock makes it more difficult for predators to see them when they are near sandy ocean floors.[15] They are a relatively fast-growing and short-lived species, currently representing a major biological component of the Bering Sea ecosystem.[2] It has been found that catches of Alaska pollock go up three years after stormy summers. The storms stir up nutrients, and this results in phytoplankton being plentiful for longer, which in turn allows more pollock hatchlings to survive.[16] The Alaska pollock has well-developed drumming muscles[17] that the fish use to produce sounds during courtship, like many other gadids.[18][19]

Foraging behavior

The primary factor in determining the foraging behavior of the Alaskan pollock is age. Young pollocks can be divided into two sub-groups, fish with lengths below 60 mm (2.4 in) and fish greater than 60 mm. Both groups mainly feed on copepods.[20] However, the latter group will also forage for krill.[20] Therefore, food depletion has a larger effect on smaller pollocks.[20]

The variation in size of each subgroup also affects seasonal foraging behavior. During the winter, when food is scarce, foraging can be costly due to the fact that longer hunting time increases the risk of meeting a predator. The larger young pollocks have no need to hunt during the winter because they have a higher capacity for energy storage, while smaller fish do not, and have to continue foraging, putting them at greater risk. To maximize their chances of survival, large pollock increase their calorie intake in autumn to gain weight, while smaller ones focus solely on growing in size.[21]

Alaskan pollock exhibit diel vertical migration, following the seasonal movement of their food. Although pollocks exhibit vertical movement during the day, their average depth changes with the seasons. Originally, the change in depth was attributed to the amount of light or water temperature, but in fact, it follows the movement of food species.[22] In August, when food is abundantly available near the surface, pollocks will be found at shallower depths. In November, they are found deeper along with their planktonic food source.[22]

Distribution

Alaska pollock in the Pacific Ocean

The Alaska pollock's main habitats are the coastal areas of the Northern Pacific, especially the waters off Alaska (Eastern Bering Sea, Gulf of Alaska, Aleutian Islands) as well as off Russia, Japan and Korea (Western Bering Sea and Sea of Okhotsk). The largest concentrations of Alaska pollock are found in the eastern Bering Sea.[2]

Small populations in the Arctic Ocean (Barents Sea)

Very small populations of fish genetically identical to Gadus chalcogrammus are found in the Barents Sea waters of northern Norway and Russia.[23] This fish was initially described as its own species under the taxon Theragra finnmarchica by Norwegian zoologist Einar Koefoed in 1956.[24] The common name used for the fish was "Norway pollock". Genetic analyses have shown that the fish is genetically identical to the Alaska pollock. It is therefore considered to be conspecific with the Pacific species and is attributed to Gadus chalcogrammus. The history of the species in the Barents Sea is unknown.[25]

The initial specification as an own species by Koefoed was based on two specimens landed in Berlevåg, northern Norway, in 1932 (hence the Norwegian name, Berlevågfisk). Based on morphological differences, Koefoed considered Theragra finnmarchica a new species, related to but separate from the Alaska pollock.[24] Just seven specimens of the fish are known to have been caught between 1957 and early 2002 in the Arctic Ocean.[26] In 2003 and 2004, 31 new specimens were caught. All specimens were large (465–687 mm (18.3–27.0 in) in total length) and caught in the coastal waters between Vesterålen in the west and Varangerfjord in the east. By 2006, 54 individuals had been recorded.[14] Sequencing of mitochondrial DNA of two specimens of Theragra finnmarchica and 10 Theragra chalcogramma (today: Gadus chalcogrammus) revealed no significant genetic differences, leading Ursvik et al.[27] to suggest that T. finnmarchica and T. chalcogramma are the same species. An analysis of a much larger sample size (44 T. finnmarchica and 20 T. chalcogramma) using both genetic and morphological methods led to similar conclusions.[14] While the putative species could not be separated genetically, they showed some consistent differences in morphology. Only one characteristic showed no overlap. Byrkjedal et al.[14] conclude that T. finnmarchica should be considered a junior synonym of T. chalcogramma. These analyses also suggest that T. finnmarchica is a near relative of the Atlantic cod, and that both Alaska and Norway pollock should be moved to genus Gadus.[14]

Norway pollock (Theragra finnmarchica) was listed as Near Threatened in the 2010 Norwegian Red List for Species[28] based on criteria D1: "Very small or geographically very restricted population: Number of mature individuals". It is currently not listed in the IUCN Red List.

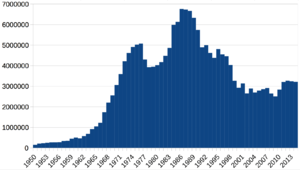

Fisheries

The Alaska pollock has been said to be "the largest remaining source of palatable fish in the world".[30] Around 3 million tons of Alaska pollock are caught each year in the North Pacific, from Alaska to northern Japan. Alaska pollock is the world's second most important fish species in terms of total catch.[31]

Alaska pollock landings are the largest of any single fish species in the U.S, with the average annual Eastern Bering Sea catch between 1977 and 2014 being 1.174 million tons.[32] Alaska pollock catches from U.S. fisheries have been quite consistent at about 1.5 million tons a year, almost all of it from the Bering Sea. Each year's quota is adjusted based on stock assessments conducted by the Alaska Fisheries Science Center.[33] For instance, stock declines in 2008[34] meant decreased allowable harvests for 2009 and 2010. This decline led some scientists to worry that Alaska pollock could be about to repeat the collapse of the Atlantic cod, which could have negative consequences for the world food supply and the Bering Sea ecosystem. Halibut, salmon, endangered Steller sea lions, fur seals, and humpback whales all eat pollock and rely on healthy populations to sustain themselves.[35] Alaska pollock stocks (and catch levels) subsequently returned to above average in 2011 and remained above average through 2014.[32] However, Greenpeace has long been critical of Alaska pollock management, placing the fish on its "red list" of species due to damage of the seabed from trawling.[36]

Other groups have hailed the fishery as an example of good management, and the Marine Stewardship Council declared it "sustainable".[37] The Marine Conservation Society rates Alaska pollock trawled from the Gulf of Alaska, Bering Sea, and Aleutian Islands as sustainable, but not those from the Western Bering Sea and Sea of Okhotsk.[38]

Pollock larvae

Pollock larvae Juvenile pollock

Juvenile pollock Adult pollock

Adult pollock 70 ton catch of Alaska pollock

70 ton catch of Alaska pollock

As food

Compared to other cod species and pollock, Alaska pollock has a milder taste, whiter color and lower oil content.

Fillets

High-quality, single-frozen whole Alaska pollock fillets may be layered into a block mold and deep-frozen to produce fish blocks that are used throughout Europe and North America as the raw material for high-quality breaded and battered fish products. Lower-quality, double-frozen fillets or minced trim pieces may also be frozen in block forms and used as raw material for lower-quality, low-cost breaded and battered fish sticks and portions.

Alaska pollock is commonly used in the fast food industry in products such as McDonald's Filet-O-Fish sandwich and (now-discontinued) Fish McBites,[39] Arby's Classic Fish sandwich,[40] Long John Silver's Baja Fish Taco,[41] Birds Eye's Fish Fingers in Crispy Batter[42] and Captain D's Seafood Kitchen.[43]

Surimi

Single-frozen Alaska pollock is considered to be the premier raw material for surimi. The most common use of surimi in the United States is imitation crabmeat (also known as crab stick).

Pollock roe

Pollock roe is a popular culinary ingredient in Korea, Japan, and Russia. In Korea, the roe is called myeongnan (명란, literally 'Alaska pollock's roe'), and the salted roe is called myeongnan-jeot (명란젓, literally 'pollock roe jeotgal'). The food was introduced to Japan after World War II, and since has been called mentai-ko (明太子) in Japanese. A milder, less spicy version is usually called tarako (鱈子, literally 'cod's roe'), which is also the Japanese name for pollock roe itself. In Russia, pollock roe is consumed as a sandwich spread. The product, resembling liquid paste due to the small size of eggs and oil added, is sold canned.

Use as food in Korea

.jpg)

Alaska pollock is considered the "national fish" of Korea.[44][45] The Korean name of the fish, myeongtae (명태,明太), has also spread to some neighbouring countries: it is called mintay (минтай) in Russia and mintaj in Poland, and its roe is called mentaiko (明太子) in Japan, although the Japanese name for the fish itself is suketōdara (介党鱈). In Korea, myeongtae is called thirty-odd additional names, including saengtae (생태, fresh), dongtae (동태, frozen), bugeo (북어, dried), hwangtae (황태, dried in winter with repeated freezing and thawing), nogari (노가리, dried young), and kodari (코다리, half-dried young).[45]

Koreans have been enjoying Alaska pollock since the Joseon era. One of the earliest mentions is from Seungjeongwon ilgi (Journal of the Royal Secretariat), where a 1652 entry stated: "The management administration should be strictly interrogated for bringing in pollock roe instead of cod roe."[46] Alaska pollocks were the most commonly caught fish in Korea in 1940, when more than 270,000 tonnes were caught from the Sea of Japan (East Sea).[47] It outnumbers the current annual consumption of Alaska pollock in South Korea, estimated at about 260,000 tonnes in 2016.[48] Nowadays, however, Alaska pollock consumption in South Korea rely heavily on import from Russia, due to rises in sea water temperatures.[49]

References

- "Taxonomy - Gadus chalcogrammus (Alaska pollock) (Theragra chalcogramma)". UniProt.

- "Walleye Pollock Research". Alaska Fisheries Science Center. NOAA. 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- Sackton, John (4 March 2014). "FDA Changes Scientific Name of Walleye Pollock, but Has Not Ruled on Market Name Change to 'Pollock'". Seafood News.

- Byrkjedal, I.; Rees, D. J.; Christiansen, Jørgen S.; Fevolden, Svein-Erik (2008-10-01). "The taxonomic status of Theragra finnmarchica Koefoed, 1956 (Teleostei: Gadidae): perspectives from morphological and molecular data". Journal of Fish Biology. 73 (5): 1183–1200. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.01958.x.

- Carr, Steven M.; Marshall, H. Dawn (2008). "Phylogeographic analysis of complete mtDNA genomes from walleye pollock (Gadus chalcogrammus Pallas, 1811) shows an ancient origin of genetic biodiversity". Mitochondrial DNA. 19 (6): 490–496. doi:10.1080/19401730802570942.

- "Pollock is Pollock". FishWatch. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- Valanes, Øystein. "Alaska pollock versus cod. An outline of the genus Gadus and possible consequences for the market" (PDF). Norwegian Seafood Council.

- "NOAA says Alaska pollock now a cod – name officially changed from Theragra spp. to Gadus". SavingSeafood.com. 21 January 2014.

- "FDA changes cod listing, still calls it Alaska pollock". SeafoodSource.com. 4 March 2015.

- "Whitefish Buyers Guide". Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute. 2005. Archived from the original on 26 September 2006.

- "Alaska pollock". SeafoodSource.com. 23 January 2014.

- Doré, Ian (1991). The New Fresh Seafood Buyer's Guide: A manual for distributors, restaurants, and retailers. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 126. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-5990-7. ISBN 978-1-4757-5990-7.

- "Alaska Pollock". FishBase.

- Byrkjedal, I.; Rees, D. J.; Christiansen, Jørgen S.; Svein-Erik Fevolden (2008-10-01). "The taxonomic status of Theragra finnmarchica Koefoed, 1956 (Teleostei: Gadidae): perspectives from morphological and molecular data". Journal of Fish Biology. 73 (5): 1183–1200. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.01958.x. ISSN 1095-8649.

- "Alaska Pollock". FishWatch. NOAA. 29 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- Pearson, Aria (6 January 2009). "Why storms are good news for fishermen". New Scientist. Reed Business Information. Archived from the original on 27 January 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- Hawkins, A. D.; Rasmussen, K. J. (1978). "The calls of gadoid fish". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 58 (4): 891–911. doi:10.1017/s0025315400056848.

- Yong-Seok Park; Yasunori Sakurai; Tohru Mukai; Kohji Iida; Noritatsu Sano (2004). "Sound production related to the reproductive behavior of captive walleye pollock". Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi (in Japanese and English). 60 (4): 467–472. doi:10.2331/suisan.60.467. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-05.

- Skjæraasen, Jon Egil; Meager, JustinJ.; Heino, Mikko (2012). "Secondary sexual characteristics in codfishes (Gadidae) in relation to sound production, habitat use and social behaviour". Marine Biology Research. 8 (3): 201–209. doi:10.1080/17451000.2011.637562. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- Ciannelli, L.; Brodeur, R. D.; Napp, J. M. (2004). "Foraging impact on zooplankton by age-0 walleye Pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) around a front in the southeast Bering Sea". Marine Biology. 144 (3): 515–526. doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1215-4. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- Heintz, Ron A.; Vollenweider, Johanna J. (2010-09-30). "Influence of size on the sources of energy consumed by overwintering walleye pollock (Theragra chalcogramma)" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 393 (1–2): 43–50. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2010.06.030.

- Adams, Charles F.; Foy, Robert J.; Kelley, John J.; Coyle, Kenneth O. (2009-08-08). "Seasonal changes in the diel vertical migration of walleye pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) in the northern Gulf of Alaska". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 86 (2): 297–305. doi:10.1007/s10641-009-9519-y. ISSN 0378-1909.

- Privalikhin, A. M.; Norvillo, G. V. (2010). "On the finding of a rare species—Norwegian pollock Theragra finnmarchica Koefoed, 1956 (Gadidae)—in the Barents Sea". Journal of Ichthyology. 50 (2): 143–147. doi:10.1134/S0032945210020013.

- Koefoed, Einar (1956). "'Theragra finnmarchica' n. sp. A fish caught off Berlevåg allied to the Alaskan pollack, 'Theragra chalcogramma' Pallas from the Bering Sea". Fiskeridirektoratets Skrifter, Serie Havundersøkelser. 11 (5): 3–11.

- Christiansen, Jørgen S.; Svein-Erik Fevolden; Ingvar Byrkjedal (2009). "Berlevågfisken - en nordnorsk torskefisk med aner i Stillehavet (The Gadoid Fish Berlevågfisk)". In Ann-Lisbeth Agnalt; et al. (eds.). Kyst og havbruk 2009. Fisken og havet. Bergen, Norway: Institute of Marine Research. pp. 54–55.

- Christiansen, Jørgen S.; Svein-Erik Fevolden; Ingvar Byrkjedal (2005-04-01). "The occurrence of Theragra finnmarchica Koefoed, 1956 (Teleostei, Gadidae), 1932–2004". Journal of Fish Biology. 66 (4): 1193–1197. doi:10.1111/j.0022-1112.2005.00682.x. ISSN 1095-8649.

- Ursvik, Anita; Breines, Ragna; Christiansen, Jørgen S.; Fevolden, Svein-Erik; Coucheron, Dag H.; Johansen, Steinar D. (2007-06-07). "A mitogenomic approach to the taxonomy of pollocks: 'Theragra chalcogramma' and 'T. finnmarchica' represent one single species". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7 (1): 86. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-86. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 1894972. PMID 17555567.

- "Theragra finnmarchica". Artsdatabanken.no. Archived from the original on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- "Species Fact Sheets: Theragra chalcogramma (Pallas, 1811)". Food and Agriculture Organization. United Nations.

- Clover, Charles (2004). The End of the Line: How Overfishing Is Changing the World and What We Eat. Ebury Press. ISBN 978-0-09-189780-2.

- The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2010. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2010. ISBN 978-92-5-106675-1.

- "Assessment of the walleye pollock stock in the Eastern Bering Sea" (PDF). Alaska Fisheries Science Center. December 2014.

- "North Pacific Groundfish Stock Assessments". Alaska Fisheries Science Center.

- Bernton, Hal. "Business & Technology | Seattle trawlers may face new limits on pollock fishery". Seattle Times. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- "Rethinking Sustainability - A new paradigm for fisheries management" (PDF). Greenpeace. March 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-17. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

- "Greenpeace Seafood Red list". Greenpeace. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- "WWF - Alaskan & Russian Pollock". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

- "Good Fish Guide". Marine Conservation Society UK. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Tepper, Rachel (24 January 2013). "McDonald's Sustainable Fish: All U.S. Locations To Serve MSC-Certified Seafood". Huffington Post. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- "Classic Fish". Arbys.com. 2014. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- "Ingredient Statements" (PDF). Ljsilvers.com. June 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-08. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- "Fish Fingers in Crispy Batter". Birdseye.co.uk. 2014. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- "Pollock". Captain D's. 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- 정, 빛나 (11 October 2016). "국민생선 명태가 돌아온다…세계최초 '완전양식' 성공" [Return of the national fish: the first success in the world in completely controlled culture of Alaska pollock]. Yonhap (in Korean). Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- 박, 효주 (6 January 2017). "동태·북어·노가리, 겨울엔 황태·코다리로… '국민생선' 제철만났네" [Dongtae, bugeo, and nogari; as hwangtae and kodari in winter... the 'national fish' is in season]. Bridgenews (in Korean). Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Cha, Sang-eun (12 September 2015). "A hit abroad, pollock roe is rallying at home". Korea Joongang Daily. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- 박, 구병. "명태" [myeongtae]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Gergen, Eugene (21 November 2016). "South Korea Facing Pollock Shortage, Aims to Rebuild Imports and Trade Ties to Russia". SeafoodNews. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Lee, Hyo-sik (19 January 2012). "PyeongChang: birthplace of yellow dried pollack". The Korea Times. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

External links

- NOAA NMFS: U.S. Seafood Facts

- FISHINFOnetwork Market Report 04/07

- FishBase: Alaska Pollock

- Alaska pollock fishery profiles Status of these fisheries, summarised on FisheriesWiki

.png)