The Station nightclub fire

The Station nightclub fire occurred on Thursday, February 20, 2003, in West Warwick, Rhode Island, United States, killing 100 people including Great White guitarist Ty Longley and injuring 230. The fire was caused by pyrotechnics set off by the tour manager of the evening's headlining band, Great White, which ignited flammable acoustic foam in the walls and ceilings surrounding the stage. The blaze reached flashover within one minute, causing all combustible materials to burn. Intense black smoke engulfed the club in 5½ minutes. Video footage of the fire shows its ignition, rapid growth, the billowing smoke that quickly made escape impossible, and blocked egress that further hindered evacuation.

| Date | February 20, 2003 |

|---|---|

| Time | 11:07 p.m. |

| Location | West Warwick, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 41°41′03.5″N 71°30′39″W |

| Cause | Ignition of acoustic foam by use of fireworks |

| Deaths | 100

|

| Non-fatal injuries | 230 |

The toxic smoke, heat, and the resulting human rush toward the main exit killed 100; 230 were injured and another 132 escaped uninjured. Many of the survivors developed post traumatic stress disorder as a result of psychological trauma.[1] This fire was the fourth-deadliest at a nightclub in U.S. history, and the second-deadliest in New England, surpassed by the 1942 Cocoanut Grove fire, which resulted in 492 deaths.

Fire

Ignition

The fire started just seconds into the band's opening song, their 1991 Billboard Mainstream Rock hit "Desert Moon", when pyrotechnics set off by tour manager Daniel Biechele ignited flammable acoustic foam on both sides and the top centre of the drummer's alcove at the back of the stage. The pyrotechnics were gerbs, cylindrical devices that produce a controlled spray of sparks. Biechele used four gerbs set to spray sparks 15 feet (4.6 m) for fifteen seconds. Two gerbs were at 45-degree angles, with the middle two pointing straight up. The flanking gerbs became the principal cause of the fire.

The acoustic foam was installed in two layers, with highly flammable urethane foam above polyethylene foam, the latter being difficult to ignite but releasing much more heat once ignited by the less dense urethane. Burning polyurethane foam instantly develops opaque, dark smoke along with deadly carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide gas. Inhaling this smoke only 2–3 times would cause rapid loss of consciousness and, eventually, death by internal suffocation.

The flames were initially thought to be part of the act (the song's music video clearly shows flames blazing around the musicians); only as the fire reached the ceiling and smoke began to bank down did people realize it was uncontrolled. Twenty seconds after the pyrotechnics ended, the band stopped playing and lead vocalist Jack Russell calmly remarked into the microphone, "Wow... that's not good." In less than a minute, the entire stage was engulfed in flames, with most of the band members and entourage fleeing for the west exit by the stage.

Casualties

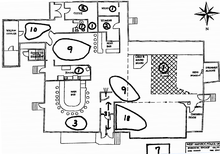

By this time, the nightclub's fire alarm had activated, and although there were four possible exits, most people headed for the front door through which they had entered. The ensuing stampede led to a crush in the narrow hallway leading to that exit, quickly blocking the exit completely and resulting in numerous deaths and injuries among the patrons and staff. A total of 462 people were in attendance, even though the club's official licensed capacity was 404.[2] One hundred lost their lives, and about half of the survivors were injured, either from burns, smoke inhalation, thermal trauma, or trampling.

Among those who died in the fire were Great White's lead guitarist, Ty Longley, and the show's emcee, WHJY DJ Mike "The Doctor" Gonsalves. There is reason to believe that Longley and Gonsalves tried to salvage equipment during the early stage of the fire and lost valuable time to escape before dense, toxic smoke made breathing near impossible at zero visibility. Longley is believed to have initially made it out of the building but then re-entered in an attempt to rescue his guitar.[3] Furthermore, a number of survivors later stated that a bouncer stopped people trying to escape via the stage exit, stating that the door was "for the band only."[4][5]

Recording and account

The fire, from its inception, was caught on videotape by cameraman Brian Butler for WPRI-TV of Providence, and the beginning of that tape was released to national news stations. Butler was there for a planned piece on nightclub safety being reported by Jeffrey A. Derderian, a WPRI news reporter who was also a part-owner of The Station. WPRI-TV would later be cited for conflict of interest in having a reporter do a report concerning his own property.[6] The report had been inspired by the E2 nightclub stampede in Chicago that had claimed twenty-one lives only three days earlier. At the scene of the fire, Butler gave this account of the tragedy:[7]

...It was that fast. As soon as the pyrotechnics stopped, the flame had started on the egg-crate backing behind the stage, and it just went up the ceiling. And people stood and watched it, and some people backed off. When I turned around, some people were already trying to leave, and others were just sitting there going, 'Yeah, that's great!' And I remember that statement, because I was, like, this is not great. This is the time to leave.

At first, there was no panic. Everybody just kind of turned. Most people still just stood there. In the other rooms, the smoke hadn't gotten to them, the flame wasn't that bad, they didn't think anything of it. Well, I guess once we all started to turn toward the door, and we got bottle-necked into the front door, people just kept pushing, and eventually everyone popped out of the door, including myself.

That's when I turned back. I went around back. There was no one coming out the back door anymore. I kicked out a side window to try to get people out of there. One guy did crawl out. I went back around the front again, and that's when you saw people stacked on top of each other, trying to get out of the front door. And by then, the black smoke was pouring out over their heads.

I noticed when the pyro stopped, the flame had kept going on both sides. And then on one side, I noticed it come over the top, and that's when I said, 'I have to leave.' And I turned around, I said, 'Get out, get out, get to the door, get to the door!' And people just stood there.

There was a table in the way at the door, and I pulled that out just to get it out of the way so people could get out easier. And I never expected it to take off as fast as it did. It just—it was so fast. It had to be two minutes tops before the whole place was black smoke.

Investigation

In the days after the fire, there were considerable efforts to assign and avoid blame on the part of the band, the nightclub owners, the manufacturers and distributors of the foam material and pyrotechnics, and the concert promoters. Through attorneys, club owners said they did not give permission to the band to use pyrotechnics. Band members claimed they had permission.

A National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) investigation of the fire under the authority of the National Construction Safety Team Act, using computer simulations with FDS and a mockup of the stage area and dance floor, concluded that a fire sprinkler system would have contained the fire long enough to give everyone time to exit safely.[8] However, because of the building's age (built in 1946[8]) and size (4,484 square feet [417 m2] [sic][8][note 1]), many believed The Station to be exempt from sprinkler system requirements. In fact, the building had undergone an occupancy change when it was converted from a restaurant to a nightclub. This change dissolved its exemption from the law, a fact that West Warwick fire inspectors never noticed. On the night in question, The Station was legally required to have a sprinkler system but did not;[10] outcry over the event has sparked calls for a national Fire Sprinkler Incentive Act, but those efforts have so far stalled .[11]

On December 9, 2003, brothers Jeffrey A. and Michael A. Derderian, the two owners of The Station nightclub, and Daniel M. Biechele, Great White's road manager at the time of the fire, were each charged with 200 counts of involuntary manslaughter—two per death, because they were indicted under two separate theories of the crime: criminal-negligence manslaughter (resulting from a legal act in which the accused ignores the risks to others and someone is killed) and misdemeanor manslaughter (resulting from a petty crime that causes a death). The brothers pleaded not guilty to the charges, while Biechele pleaded guilty. The Derderians also were fined $1.07 million for failing to carry workers' compensation insurance for their employees, four of whom died in the blaze.

Band manager's trial

Daniel Michael Biechele | |

|---|---|

| Born | October 8, 1976 |

| Occupation | Flooring company accountant |

| Criminal status | Paroled March 19, 2008 |

| Conviction(s) | Pleaded guilty Sentenced May 10, 2006 |

| Criminal charge | 100 counts of involuntary manslaughter |

| Penalty | 15 years: 4 years to serve 11 years suspended + 3 years' probation |

The first criminal trial was against Great White's tour manager, Daniel Michael Biechele, 26, from Orlando, Florida. This trial was scheduled to start May 1, 2006, but Biechele, against his lawyers' advice,[12] pleaded guilty to 100 counts of involuntary manslaughter on February 7, 2006, in what he said was an effort to "bring peace, I want this to be over with."[12]

Sentencing and statement

On May 10, 2006, State Prosecutor Randall White asked that Biechele be sentenced to ten years in prison, the maximum allowed under the plea bargain, citing the massive loss of life in the fire and the need to send a message.[12] Speaking to the public for the first time since the fire, Biechele appeared remorseful during his sentencing. Choking back tears, he made a statement to the court and to the families of the victims.

For three years, I've wanted to be able to speak to the people that were affected by this tragedy, but I know that there's nothing that I can say or do that will undo what happened that night.

Since the fire, I have wanted to tell the victims and their families how truly sorry I am for what happened that night and the part that I had in it. I never wanted anyone to be hurt in any way. I never imagined that anyone ever would be.

I know how this tragedy has devastated me, but I can only begin to understand what the people who lost loved ones have endured. I don't know that I'll ever forgive myself for what happened that night, so I can't expect anybody else to.

I can only pray that they understand that I would do anything to undo what happened that night and give them back their loved ones.

I'm so sorry for what I have done, and I don't want to cause anyone any more pain.

I will never forget that night, and I will never forget the people that were hurt by it.

I am so sorry.[13]

Superior Court Judge Francis J. Darigan Jr. sentenced Biechele to fifteen years in prison, with four to serve and eleven years suspended, plus three years' probation, for his role in the fire.[14] Darigan remarked, "The greatest sentence that can be imposed on you has been imposed on you by yourself." Under this sentence, with good behavior, Biechele would be eligible for parole in September 2007. Judge Darigan deemed Biechele highly unlikely to re-offend, which was among the mitigating factors that led to his decision to impose this sentence.

The sentence drew mixed reactions in the courtroom. Many of the families believed that the punishment was just; others had hoped for a more severe sentence.[15]

Support for parole

On September 4, 2007, some families of the fire's victims expressed their support for Biechele's parole. Leland Hoisington, whose 28-year-old daughter, Abbie, was killed in the fire, told reporters, "I think they should not even bother with a hearing—just let Biechele out... I just don't find him as guilty of anything." The state parole board received approximately twenty letters, the majority of which expressed their sympathy and support for Biechele, some going as far as to describe him as a "scapegoat" with limited responsibility. Board chairwoman Lisa Holley told journalists of her surprise at the forgiving attitude of the families, saying, "I think the most overwhelming part of it for me was the depth of forgiveness of many of these families that have sustained such a loss."

Dave Kane and Joanne O'Neill, parents of youngest victim Nicholas O'Neill, released their letter to the board to reporters. "In the period following this tragedy, it was Mr. Biechele, alone, who stood up and admitted responsibility for his part in this horrible event... He apologized to the families of the victims and made no attempt to mitigate his guilt," the letter said. Others pointed out that Biechele had sent handwritten letters to the families of each of the 100 victims and that he had a work release position in a local charity.

On September 19, 2007, the Rhode Island Parole Board announced that Biechele would be released in March 2008. Biechele was released from prison on March 19, 2008. As reported by the Associated Press, he did not answer any questions and was quickly whisked away in a waiting car.

Nightclub owners' trial

Following Biechele's trial, The Station's owners, Michael and Jeffrey Derderian, were scheduled to receive separate trials. However, on September 21, 2006, Judge Darigan announced that the brothers had changed their pleas from "not guilty" to "no contest," thereby avoiding a trial.[16] Michael Derderian received fifteen years in prison, with four to serve and eleven years suspended, plus three years' probation—the same sentence as Biechele. Jeffrey Derderian received a ten-year suspended sentence, three years' probation, and 500 hours of community service.

In a letter to the victims' families,[17] Judge Darigan said that a trial "would only serve to further traumatize and victimize not only the loved ones of the deceased and the survivors of this fire, but the general public as well." He added that the difference in the brothers' sentences reflected their respective involvement with the purchase and installation of the flammable foam. Rhode Island Attorney General Patrick C. Lynch objected strenuously to the plea bargain, saying that both brothers should have received jail time and that Michael Derderian should have received more time than Biechele.[16]

In January 2008, the Parole Board decided to grant Michael Derderian an early release; he was scheduled to be released from prison in September 2009, but was granted his release in June 2009 for good behavior.[18]

Civil settlements

As of September 2008, at least $115 million in settlement agreements had been paid, or offered, to the victims or their families by various defendants:

- In September 2008, The Jack Russell Tour Group Inc. offered $1 million in a settlement to survivors and victims' relatives,[19] the maximum allowed under the band's insurance plan.[20]

- Club owners Jeffrey and Michael Derderian have offered to settle for $813,000,[21] which is to be covered by their insurance plan due to the pair having bankruptcy protection from lawsuits.[21]

- The State of Rhode Island and the town of West Warwick agreed to pay $10 million as settlement.[22]

- Sealed Air Corporation agreed to pay $25 million as settlement. Sealed Air made flammable packaging foam that was improperly installed in the club, which required acoustic foam designed for this purpose.[23]

- In February 2008, Providence television station WPRI-TV and their then-owners LIN TV made an out-of-court settlement of $30 million as a result of the claim that their video journalist was said to be obstructing escape and not sufficiently helping people exit.[24]

- In March 2008, JBL Speakers settled out of court for $815,000. JBL was accused of using flammable foam inside their speakers. The company denied any wrongdoing.[25]

- Anheuser-Busch has offered $5 million.[26] McLaughlin & Moran, Anheuser-Busch's distributor, has offered $16 million.[26]

- Home Depot and Polar Industries, Inc. (a Connecticut-based insulation company) made a settlement offer of $5 million.[27]

- Providence radio station WHJY-FM promoted the show, which was emcee'd by its DJ, Mike "The Doctor" Gonsalves (who was one of the casualties that night). Clear Channel Broadcasting, WHJY's parent company, paid a settlement of $22 million in February 2008.[28]

- American Foam Corporation who sold the insulation to The Station nightclub agreed in 2008 to pay $6.3 million to settle lawsuits relating to the fire.[29]

Memorialization

Thousands of mourners attended a memorial service at St. Gregory the Great Church in Warwick on February 24, 2003, to remember those lost in the fire.

Five months after the fire, Great White started a benefit tour, saying a prayer at the beginning of each concert for the friends and families affected by the incident and giving a portion of the proceeds to the Station Family Fund. In 2003, and again in 2005, the band stated they had not performed the song "Desert Moon" since the tragedy. "I don't think I could ever sing that song again," said Russell,[30] while guitarist Mark Kendall stated, "We haven't played that song. Things that bring back memories of that night we try to stay away from. And that song reminds us of that night. We haven't played it since then and probably never will."[31] By August 18, 2007, however, the band had resumed performing the song.[32]

Two years to the day after the fire, band members Russell and Kendall, along with Great White's attorney, Ed McPherson, appeared on CNN's Larry King Live with three survivors of the fire and the father of Longley, to discuss how their lives had changed since the incident.[33]

On January 16, 2013, Jack Russell scheduled a benefit show in February 2013, commemorating the tenth anniversary of the fire, and announced that all proceeds would go towards the Station Fire Memorial Foundation. Upon hearing of the event, the Foundation asked that its name be removed, stating the animosity still felt by many of the survivors and surviving families.[34] Jack Russell's management has stated that the show would be renamed and that the proceeds would go to another charity.

The site of the fire was cleared, and a multitude of crosses were placed as memorials, left by loved ones of the deceased. On May 20, 2003, nondenominational services began to be held at the site of the fire for a number of months. Access remains open to the public, and memorial services are held each February 20.[35]

A permanent memorial at the site of the fire has been erected and named the Station Fire Memorial Park.[36] In August 2016, the site was reported to have been being used as a PokeStop in Pokémon Go, to uproar from victims' families.[37]

In June 2003, the Station Fire Memorial Foundation (SFMF) was formed with the purpose of purchasing the property, to build and maintain a memorial.[38] In September 2012, the owner of the land, Ray Villanova, donated the site to the SFMF.[39] By April 2016, $1.65 million of the $2 million fundraising goal had been achieved and construction of the Station Fire Memorial Park had commenced.[40][41] The memorial dedication ceremony took place on May 21, 2017.[42]

Code changes and other consequences

Other nightclub fires

There have been other nightclub fires in the United States that also resulted in significant loss of life. The November 28, 1942 Cocoanut Grove fire in Boston caused 492 deaths. The April 23, 1940 Rhythm Night Club Fire in Natchez, Mississippi, claimed the lives of approximately 209 people. The May 28, 1977 Beverly Hills Supper Club fire in Southgate, Kentucky, claimed 165 lives. The December 2, 2016 Ghost Ship warehouse fire in Oakland, California claimed 36 lives. The March 25, 1990 Happy Land Fire in the Bronx, New York City, claimed 87 lives. The deadliest single-building fire in United States history was the December 30, 1903 Iroquois Theatre fire in Chicago, with at least 602 deaths.

Great White

Following the fire, Great White split into two separate groups, one led by Russell and the other by Kendall.[43] Neither version of the band performed in any of the six New England states for over a decade.[43] Russell's group made its first New England appearance in twelve years at a harvest festival in Mechanic Falls, Maine in August 2015.[43]

Popular culture

The season 1 episode of Cold Case "Disco inferno" was based on this incident. The season 14 episode of Law & Order "Blaze" was also closely based on the incident. The season 1 episode of CSI: Miami "Tinder Box" featured a DJ's pyrotechnics setting fire to a nightclub.

Safety measures

Following the tragedy, Governor Donald Carcieri declared a moratorium on pyrotechnic displays at venues that hold fewer than 300 people.

Numerous violations of existing codes contributed to the calamity, triggering an immediate effort to strengthen fire code protections. Within weeks of the disaster, an emergency meeting was called for the National Fire Protection Association committee handling code for "assembly occupancies". Based upon its work, Tentative Interim Amendments (TIAs) were issued for the national standard "Life Safety Code" (NFPA 101), in July 2003. The TIAs required automatic fire sprinklers in all existing nightclubs and similar locations that accommodate more than 100 occupants, and all new locations in the same categories. The TIAs also required additional crowd manager personnel, among other things. These TIAs were subsequently incorporated into the 2006 edition of NFPA 101, along with additional exit requirements for new nightclub occupancies.[44] It is left for each state or local jurisdiction to legally enact and enforce the current code changes.

As a result of this and other similar incidents, fire chiefs, fire marshals and inspectors require trained crowd managers to comply with the International Fire Code, NFPA-101 Life Safety Code, NFPA-1 Fire Code and many local ordinances that address safety in public-assembly occupancies. However, fire professionals have few choices about what training should be provided and training programs are continually updated to incorporate new technologies as well as lessons learned from actual fire experiences.[45]

See also

References

- "The Station fire took emotional toll on survivors, study finds". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- Parker, Paul Edward (December 3, 2007). "Tally of a tragedy: 462 were in The Station on night of fire". The Providence Journal.

- "The Great White Nightclub Fire: Ten Years Later". July 15, 2013.

- Katie Roach (ed.). "Episode 1 Gina Russo 'Black Rain'" (video). YouTube. The Station web series. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- Katie Roach (ed.). "Episode 4 Rob Feeney 'Flashover'" (video). YouTube. The Station web series. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- Elliott, Deni. "Ethics Matters". News Photographer. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved December 7, 2007.

- Butler, Brian (February 21, 2003). "Nightclub Fire Kills 39 People". CNN.

- Kuntz, K.; Madrzykowski, Daniel M.; Bryner, Nelson P.; Grosshandler, William L. (June 30, 2005). "NIST Manuscript Publication Search". nist.gov. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- Thomas J. Bruno and Paris D.N. Svoronos. CRC Handbook of Basic Tables for Chemical Analysis, Third Edition. CRC Press, 2010. ISBN 9781420080438 p. 785.

- Arsenault, Mark (April 4, 2007). "Building official: R.I. code required sprinklers". The Providence Journal.

- Nightclub Inferno Sparked an Industry’s Push, Roll Call, May 27, 2010

- Peoples, Steve (May 10, 2006). "Prosecutor wants 10 years for Biechele". The Providence Journal. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kVvm1qUOh-Y

- Perry, Jack (May 10, 2006). "Biechele gets 4 years to serve". The Providence Journal. Archived from the original on June 22, 2011.

- "Manager Sentenced for Rhode Island Nightclub Fire". The New York Times. May 10, 2006. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- Breton, Tracy (September 21, 2006). "Derderians will plead; AG says he opposes sentencing deal". The Providence Journal.

- "Darigan's letter to families" (PDF). Retrieved July 14, 2011.

- Tucker, Eric (January 17, 2008). "Co-owner of R.I. club where 100 died to be released early". The Boston Globe. Associated Press.

- "Band to pay $1M in case over deadly club fire". Archived from the original on September 3, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- Tucker, Eric (September 2, 2008). "Great White offers $1M to settle fatal fire suits". Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

Great White's insurer is covering the settlement. The insurer has previously said that $1 million was the maximum amount of the band's insurance policy.

- Tucker, Eric (September 3, 2008). "RI nightclub owners reach settlement in fatal fire". Associated Press. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

Jeffrey and Michael Derderian, the owners of The Station nightclub in West Warwick, have reached an $813,000 settlement with survivors and relatives of those killed, according to court papers filed Wednesday. The settlement will be covered entirely by their insurance policy since the brothers have received bankruptcy protection that shielded them from lawsuits.

- "Governments offer $20 million in RI nightclub fire". Archived from the original on August 22, 2008. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- "Packing co. settles for $25M in nightclub fire - News - Turnto10". Archived from the original on July 25, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- Estes, Andrea (February 2, 2008). "Tentative deal set in R.I. fire case". The Boston Globe.

- "JBL Settles On Station Fire Lawsuit". Archived from the original on May 6, 2008. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- PBN staff (May 27, 2008). "McLaughlin & Moran, Anheuser-Busch offer $21M settlement in Station fire case". Providence Business News. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

'Under the proposal, the carriers would pay $16 million for settlement of all claims against McLaughlin & Moran.' The other $5 million would be paid by St. Louis-based Anheuser-Busch, the nation's largest brewer.

- Staff reporter (February 13, 2008). "Home Depot Settles In R.I. Nightclub Fire". Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 1, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

Home Depot Inc. and a Connecticut insulation company have tentatively agreed to a $5 million settlement in lawsuits brought by survivors of a 2003 nightclub fire and relatives of the 100 people killed, a lawyer for the families said Wednesday.

- PBN staff (February 13, 2008). "WHJY, Clear Channel offer $22M Station fire settlement". Providence Business News. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

Local radio station 94 WHJY-FM and parent company Clear Channel Communications Inc. (NYSE: CCU) have reached a tentative $22 million settlement of lawsuits brought by victims and survivors of the fatal nightclub fire five years ago in West Warwick, Clear Channel said today.

- Henson, Shannon. "Foam Company Settles Club Fire Claims". Law360. LexisNexis. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- Arsenault, Mark (July 31, 2003). "Great White: Performing again is the right thing". The Providence Journal.

- Mervis, Scott (March 25, 2005). "After the fire: Great White, survivors live with the horror of Rhode Island tragedy". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- "Great White - Desert Moon (Springfield, VA - 08-18-2007)". YouTube. August 19, 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- Episode Transcripts (February 9, 2005). "Rhode Island Club Fire Tragedy Revisited with Members of Rock Band Great White". Larry King Live. CNN. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- "Great White singer's fire memorial concert nixed". Los Angeles Times. January 18, 2013. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013.

- Laguarda, Ignacio (March 22, 2015). "Station Nightclub Fire Memorial On Track For 2016 Opening". Hartford Courant. Associated Press. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- "Timeline: Station Nightclub Fire, 15 year anniversary". Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- "'Pokemon Go' stop at site of deadly nightclub fire upsets families". WCVB Boston. August 9, 2016. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016.

- "Our Mission". The Station Fire Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on July 11, 2007. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Smith, Michelle R. (December 28, 2012). "Owner of burned RI club donates land for memorial". AP. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Beacon staff writers (April 5, 2016). "Job Lot customers respond to Station Fire Memorial drive". Warwick Beacon. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- "SFM Park". The Station Fire Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on May 26, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Towne, Shaun (May 21, 2017). "Memorial park dedicated to victims of Station Nightclub Fire". WPRI.

- Christopher, Michael (August 4, 2015). "After The Fire: Feelings mixed and emotions high as Jack Russell's Great White return to New England". Vanyaland. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- "Station Night Club Fire". nfpa.org. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- "Crowd Manager Training". www.iafc.org. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

External links

- Boston Globe: "Portraits of People who Died in the R.I Nightclub Fire" 2003

- National Fire Protection Association web page Nightclubs/assembly occupancies Includes a report on the fire, links to nightclub safety tips, information on safe use of pyrotechnics, and other relevant information.

- NIST simulations of the fire: without sprinklers; with sprinklers

- Full NIST government investigation

- Guide to the Station Nightclub Victims' Collection from the Rhode Island State Archives