The Bookworm (short story)

"The Bookworm" (simplified Chinese: 书痴; traditional Chinese: 書癡; pinyin: Shū Chī) is a short story by Pu Songling first published in Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (1740). The story revolves around an innocent scholar Lang Yuzhu and his romantic encounter with a celestial being hidden in his books. An English translation of the story by Sidney L. Sondergard was released in 2014.

| "The Bookworm" | |

|---|---|

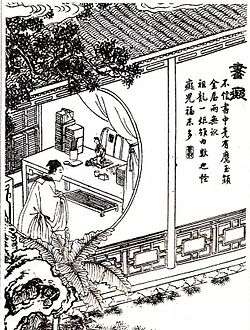

19th-century illustration from Xiangzhu liaozhai zhiyi tuyong (Liaozhai Zhiyi with commentary and illustrations; 1886) | |

| Author | Pu Songling |

| Original title | "书痴 (Shuchi)" |

| Translator | Sidney L. Sondergard |

| Country | China |

| Language | Chinese |

| Genre(s) | Zhiguai Romance |

| Published in | Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio |

| Publication type | Anthology |

| Publication date | c. 1740 |

| Published in English | 2014 |

| Preceded by | "Huangying (黃英)" |

| Followed by | "The Great Sage, Heaven's Equal (齐天大圣)" |

Background

"The Bookworm" is a "fictional extension" of a poem titled Quanxueshi (Chinese: 劝学诗; lit.: 'Poem exhorting studying') and written by Emperor Zhenzong, which highlights the importance of being well-read and learned. Parts of the poem are cited in "The Bookworm", most notably "There (in books), girls as beautiful as jade abound."[lower-alpha 1][1] Originally titled "Shuchi" (书痴) by Pu Songling, the full story was translated into English by Sidney L. Sondergard as "The Bookworm" in 2014.[2]

The Martin Bodmer Foundation Library houses a 19th-century Liaozhai manuscript, silk-printed and bound leporello-style, that contains three tales including "The Bookworm", "The Great Sage, Heaven's Equal", and "The Frog God".[3]

Plot

Lang Yuzhu (郎玉柱) is a conscientious scholar, but his scholarly ambitions have prevented him from embarking on romantic endeavours. At the same time, Lang finds himself struggling at the imperial examinations. In his twenties, he is still a loner and bachelor who fantasises about meeting "one of the beauties like those in his books",[2] believing that "(i)n books, you'll find a jade-like beauty".[4] One day, Lang finds a paper cut-out of the mythological character "Weaving Girl", daughter of the Queen Mother of the West and the Jade Emperor. He is puzzled at its meaning, only to find it growing and turning into a real girl who introduces herself as Yan Ruyu (颜如玉, literally "face like jade"). An initially frightened Lang turns "ecstatically happy" but does not know how to perform intercourse with her; Yan is turned off and chastises him for being such a bookworm.[5]

Lang relents and puts away his books for some time but eventually reverts to his usual self. In protest, Yan disappears; a distraught Lang thankfully finds her again in the same book, after which Yan warns Lang never to repeat his antics. Nevertheless, Lang continues reading obsessively behind Yan's back. Soon enough she learns of this and vanishes yet again, whereas Lang has to plead in remorse once more. Yan issues an ultimatum: in three days, Lang must have improved in his chess. On day three, he surprisingly rises to the occasion and defeats Yan in two rounds of chess.[6]

She then teaches him other things, such as string instrument-playing. They while the days away in happiness and Lang's compulsiveness in reading gradually disappears. Yan also addresses Lang's ignorance of sexual intercourse when they consummate their love that night.[7] She gives birth to a boy but informs Lang that her stay in the mortal realm is about to end, claiming that this was predetermined. Lang is forlorn but is unable to convince her to stay.[7]

Afterwards, some of Lang Yuzhu's kin, having seen Yan by chance, question him about her but Lang keeps mum. Lang and Yan become the talk of the town; magistrate Shi Mou, a Fujian native, becomes aware of this and calls in the couple for questioning.[8] Yan is nowhere to be found, whilst Lang subjects himself to punishment in silence. Shi is convinced Yan is a demon and orders an investigation of Lang's residence. When his search yields no results, he torches Lang's books.[9] In the aftermath of this incident, Lang finally attains success at the imperial examinations but remains bitter towards Magistrate Shi. He works hard as a civil servant, receives the post of censor and is sent to Fujian, where he gathers evidence and information to successfully indict Shi. With his grudge settled, Lang reunites a female slave, whom his first cousin unfairly exploited, with her family.[9]

Pu Songling notes in an appended statement: "The accumulation of possessions in this world provokes jealousy, and obsessive love of them causes evil."[lower-alpha 2]

Reception

A writer for Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR) offers in its December 1997 issue that Pu Songling could be referencing his own life as a scholar in "self-mockery".[10] Ming Donggu, in his 2006 work Chinese Theories of Fiction, praises Pu Songling for his refined employment of literary techniques in "The Bookworm" which "typifies an artistic feature in Chinese fictional art".[1] In summary, he writes that the tale is both a "credible story and a parody".[11] Similarly, Judith T. Zeitlin writes in Historian of the Strange that the "underlying strain of self-satire" is present in the story.[12] Pu, she suggests, is mocking both the "bookworm (who) is a fool because he cannot distinguish figurative and literal levels of meaning" as well as the "world and official success".[13]

In popular culture

"The Bookworm" was adapted into a two-part episode for the 1986 television series Liaozhai produced by the Fujian Television Channel Television Programme Production Company (福建电视台电视剧制作中心). It was directed by Li Xietai (李歇泰) and written by Wang Yimin (王一民).[14]

References

Citations

- Ming 2006, p. 94.

- Sondergrad 2014, p. 2070.

- "The Far East". Fondation Martin Bodmer. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

- Sondergrad 2014, p. 2072.

- Sondergrad 2014, p. 2073.

- Sondergrad 2014, p. 2074.

- Sondergrad 2014, p. 2075.

- Sondergrad 2014, p. 2076.

- Sondergrad 2014, p. 2077.

- CLEAR 1997, p. 72.

- Ming 2006, p. 95.

- Zeitlin 1997, p. 95.

- Zeitlin 1997, p. 96.

- "《聊斋》电视系列剧剧目 [Liaozhai episode list]" (in Chinese). ZBSQ. 28 July 2005. Retrieved 21 February 2016.

Bibliography

- Ming, Donggu (2006). Chinese Theories of Fiction. Suny Press. ISBN 9780791481486.

- CLEAR. 19. Coda Press. 1997.

- Zeitlin, Judith T. (1997). Historian of the Strange: Pu Songling and the Chinese Classical Tale. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804729680.

- Sondergrad, Sidney (2014). Strange Tales from Liaozhai. Jain Publishing Company. ISBN 9780895810519.