Text mining

Text mining, also referred to as text data mining, similar to text analytics, is the process of deriving high-quality information from text. It involves "the discovery by computer of new, previously unknown information, by automatically extracting information from different written resources."[1] Written resources may include websites, books, emails, reviews, and articles. High-quality information is typically obtained by devising patterns and trends by means such as statistical pattern learning. According to Hotho et al. (2005) we can differ three different perspectives of text mining: information extraction, data mining, and a KDD (Knowledge Discovery in Databases) process.[2] Text mining usually involves the process of structuring the input text (usually parsing, along with the addition of some derived linguistic features and the removal of others, and subsequent insertion into a database), deriving patterns within the structured data, and finally evaluation and interpretation of the output. 'High quality' in text mining usually refers to some combination of relevance, novelty, and interest. Typical text mining tasks include text categorization, text clustering, concept/entity extraction, production of granular taxonomies, sentiment analysis, document summarization, and entity relation modeling (i.e., learning relations between named entities).

Text analysis involves information retrieval, lexical analysis to study word frequency distributions, pattern recognition, tagging/annotation, information extraction, data mining techniques including link and association analysis, visualization, and predictive analytics. The overarching goal is, essentially, to turn text into data for analysis, via application of natural language processing (NLP), different types of algorithms and analytical methods. An important phase of this process is the interpretation of the gathered information.

A typical application is to scan a set of documents written in a natural language and either model the document set for predictive classification purposes or populate a database or search index with the information extracted. The document is the basic element while starting with text mining. Here, we define a document as a unit of textual data, which normally exists in many types of collections.[3]

Text analytics

The term text analytics describes a set of linguistic, statistical, and machine learning techniques that model and structure the information content of textual sources for business intelligence, exploratory data analysis, research, or investigation.[4] The term is roughly synonymous with text mining; indeed, Ronen Feldman modified a 2000 description of "text mining"[5] in 2004 to describe "text analytics".[6] The latter term is now used more frequently in business settings while "text mining" is used in some of the earliest application areas, dating to the 1980s,[7] notably life-sciences research and government intelligence.

The term text analytics also describes that application of text analytics to respond to business problems, whether independently or in conjunction with query and analysis of fielded, numerical data. It is a truism that 80 percent of business-relevant information originates in unstructured form, primarily text.[8] These techniques and processes discover and present knowledge – facts, business rules, and relationships – that is otherwise locked in textual form, impenetrable to automated processing.

Text analysis processes

Subtasks—components of a larger text-analytics effort—typically include:

- Dimensionality reduction is important technique for pre-processing data. Technique is used to identify the root word for actual words and reduce the size of the text data.[9]

- Information retrieval or identification of a corpus is a preparatory step: collecting or identifying a set of textual materials, on the Web or held in a file system, database, or content corpus manager, for analysis.

- Although some text analytics systems apply exclusively advanced statistical methods, many others apply more extensive natural language processing, such as part of speech tagging, syntactic parsing, and other types of linguistic analysis.[10]

- Named entity recognition is the use of gazetteers or statistical techniques to identify named text features: people, organizations, place names, stock ticker symbols, certain abbreviations, and so on.

- Disambiguation—the use of contextual clues—may be required to decide where, for instance, "Ford" can refer to a former U.S. president, a vehicle manufacturer, a movie star, a river crossing, or some other entity.[11]

- Recognition of Pattern Identified Entities: Features such as telephone numbers, e-mail addresses, quantities (with units) can be discerned via regular expression or other pattern matches.

- Document clustering: identification of sets of similar text documents.[12]

- Coreference: identification of noun phrases and other terms that refer to the same object.

- Relationship, fact, and event Extraction: identification of associations among entities and other information in text

- Sentiment analysis involves discerning subjective (as opposed to factual) material and extracting various forms of attitudinal information: sentiment, opinion, mood, and emotion. Text analytics techniques are helpful in analyzing sentiment at the entity, concept, or topic level and in distinguishing opinion holder and opinion object.[13]

- Quantitative text analysis is a set of techniques stemming from the social sciences where either a human judge or a computer extracts semantic or grammatical relationships between words in order to find out the meaning or stylistic patterns of, usually, a casual personal text for the purpose of psychological profiling etc.[14]

Applications

Text mining technology is now broadly applied to a wide variety of government, research, and business needs. All these groups may use text mining for records management and searching documents relevant to their daily activities. Legal professionals may use text mining for e-discovery, for example. Governments and military groups use text mining for national security and intelligence purposes. Scientific researchers incorporate text mining approaches into efforts to organize large sets of text data (i.e., addressing the problem of unstructured data), to determine ideas communicated through text (e.g., sentiment analysis in social media[15][16][17]) and to support scientific discovery in fields such as the life sciences and bioinformatics. In business, applications are used to support competitive intelligence and automated ad placement, among numerous other activities.

Security applications

Many text mining software packages are marketed for security applications, especially monitoring and analysis of online plain text sources such as Internet news, blogs, etc. for national security purposes.[18] It is also involved in the study of text encryption/decryption.

Biomedical applications

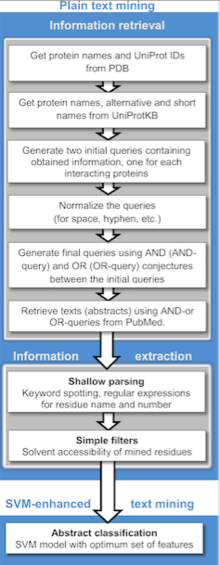

A range of text mining applications in the biomedical literature has been described,[20] including computational approaches to assist with studies in protein docking,[21] protein interactions,[22][23] and protein-disease associations.[24] In addition, with large patient textual datasets in the clinical field, datasets of demographic information in population studies and adverse event reports, text mining can facilitate clinical studies and precision medicine. Text mining algorithms can facilitate the stratification and indexing of specific clinical events in large patient textual datasets of symptoms, side effects, and comorbidities from electronic health records, event reports, and reports from specific diagnostic tests.[25] One online text mining application in the biomedical literature is PubGene, a publicly accessible search engine that combines biomedical text mining with network visualization.[26][27] GoPubMed is a knowledge-based search engine for biomedical texts. Text mining techniques also enable us to extract unknown knowledge from unstructured documents in the clinical domain[28]

Software applications

Text mining methods and software is also being researched and developed by major firms, including IBM and Microsoft, to further automate the mining and analysis processes, and by different firms working in the area of search and indexing in general as a way to improve their results. Within public sector much effort has been concentrated on creating software for tracking and monitoring terrorist activities.[29] For study purposes, Weka software is one of the most popular options in the scientific world, acting as an excellent entry point for beginners. For Python programmers, there is an excellent toolkit called NLTK for more general purposes. For more advanced programmers, there's also the Gensim library, which focuses on word embedding-based text representations.

Online media applications

Text mining is being used by large media companies, such as the Tribune Company, to clarify information and to provide readers with greater search experiences, which in turn increases site "stickiness" and revenue. Additionally, on the back end, editors are benefiting by being able to share, associate and package news across properties, significantly increasing opportunities to monetize content.

Business and marketing applications

Text mining is starting to be used in marketing as well, more specifically in analytical customer relationship management.[30] Coussement and Van den Poel (2008)[31][32] apply it to improve predictive analytics models for customer churn (customer attrition).[31] Text mining is also being applied in stock returns prediction.[33]

Sentiment analysis

Sentiment analysis may involve analysis of movie reviews for estimating how favorable a review is for a movie.[34] Such an analysis may need a labeled data set or labeling of the affectivity of words. Resources for affectivity of words and concepts have been made for WordNet[35] and ConceptNet,[36] respectively.

Text has been used to detect emotions in the related area of affective computing.[37] Text based approaches to affective computing have been used on multiple corpora such as students evaluations, children stories and news stories.

Scientific literature mining and academic applications

The issue of text mining is of importance to publishers who hold large databases of information needing indexing for retrieval. This is especially true in scientific disciplines, in which highly specific information is often contained within the written text. Therefore, initiatives have been taken such as Nature's proposal for an Open Text Mining Interface (OTMI) and the National Institutes of Health's common Journal Publishing Document Type Definition (DTD) that would provide semantic cues to machines to answer specific queries contained within the text without removing publisher barriers to public access.

Academic institutions have also become involved in the text mining initiative:

- The National Centre for Text Mining (NaCTeM), is the first publicly funded text mining centre in the world. NaCTeM is operated by the University of Manchester[38] in close collaboration with the Tsujii Lab,[39] University of Tokyo.[40] NaCTeM provides customised tools, research facilities and offers advice to the academic community. They are funded by the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) and two of the UK research councils (EPSRC & BBSRC). With an initial focus on text mining in the biological and biomedical sciences, research has since expanded into the areas of social sciences.

- In the United States, the School of Information at University of California, Berkeley is developing a program called BioText to assist biology researchers in text mining and analysis.

- The Text Analysis Portal for Research (TAPoR), currently housed at the University of Alberta, is a scholarly project to catalogue text analysis applications and create a gateway for researchers new to the practice.

Methods for scientific literature mining

Computational methods have been developed to assist with information retrieval from scientific literature. Published approaches include methods for searching,[41] determining novelty,[42] and clarifying homonyms[43] among technical reports.

Digital humanities and computational sociology

The automatic analysis of vast textual corpora has created the possibility for scholars to analyze millions of documents in multiple languages with very limited manual intervention. Key enabling technologies have been parsing, machine translation, topic categorization, and machine learning.

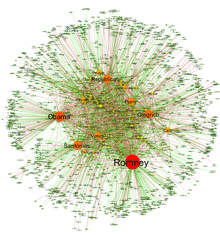

The automatic parsing of textual corpora has enabled the extraction of actors and their relational networks on a vast scale, turning textual data into network data. The resulting networks, which can contain thousands of nodes, are then analyzed by using tools from network theory to identify the key actors, the key communities or parties, and general properties such as robustness or structural stability of the overall network, or centrality of certain nodes.[45] This automates the approach introduced by quantitative narrative analysis,[46] whereby subject-verb-object triplets are identified with pairs of actors linked by an action, or pairs formed by actor-object.[44]

Content analysis has been a traditional part of social sciences and media studies for a long time. The automation of content analysis has allowed a "big data" revolution to take place in that field, with studies in social media and newspaper content that include millions of news items. Gender bias, readability, content similarity, reader preferences, and even mood have been analyzed based on text mining methods over millions of documents.[47][48][49][50][51] The analysis of readability, gender bias and topic bias was demonstrated in Flaounas et al.[52] showing how different topics have different gender biases and levels of readability; the possibility to detect mood patterns in a vast population by analyzing Twitter content was demonstrated as well.[53][54]

Software

Text mining computer programs are available from many commercial and open source companies and sources. See List of text mining software.

Intellectual property law

Situation in Europe

Under European copyright and database laws, the mining of in-copyright works (such as by web mining) without the permission of the copyright owner is illegal. In the UK in 2014, on the recommendation of the Hargreaves review, the government amended copyright law[55] to allow text mining as a limitation and exception. It was the second country in the world to do so, following Japan, which introduced a mining-specific exception in 2009. However, owing to the restriction of the Information Society Directive (2001), the UK exception only allows content mining for non-commercial purposes. UK copyright law does not allow this provision to be overridden by contractual terms and conditions.

The European Commission facilitated stakeholder discussion on text and data mining in 2013, under the title of Licenses for Europe.[56] The fact that the focus on the solution to this legal issue was licenses, and not limitations and exceptions to copyright law, led representatives of universities, researchers, libraries, civil society groups and open access publishers to leave the stakeholder dialogue in May 2013.[57]

Situation in the United States

US copyright law, and in particular its fair use provisions, means that text mining in America, as well as other fair use countries such as Israel, Taiwan and South Korea, is viewed as being legal. As text mining is transformative, meaning that it does not supplant the original work, it is viewed as being lawful under fair use. For example, as part of the Google Book settlement the presiding judge on the case ruled that Google's digitization project of in-copyright books was lawful, in part because of the transformative uses that the digitization project displayed—one such use being text and data mining.[58]

Implications

Until recently, websites most often used text-based searches, which only found documents containing specific user-defined words or phrases. Now, through use of a semantic web, text mining can find content based on meaning and context (rather than just by a specific word). Additionally, text mining software can be used to build large dossiers of information about specific people and events. For example, large datasets based on data extracted from news reports can be built to facilitate social networks analysis or counter-intelligence. In effect, the text mining software may act in a capacity similar to an intelligence analyst or research librarian, albeit with a more limited scope of analysis. Text mining is also used in some email spam filters as a way of determining the characteristics of messages that are likely to be advertisements or other unwanted material. Text mining plays an important role in determining financial market sentiment.

Future

Increasing interest is being paid to multilingual data mining: the ability to gain information across languages and cluster similar items from different linguistic sources according to their meaning.

The challenge of exploiting the large proportion of enterprise information that originates in "unstructured" form has been recognized for decades.[59] It is recognized in the earliest definition of business intelligence (BI), in an October 1958 IBM Journal article by H.P. Luhn, A Business Intelligence System, which describes a system that will:

"...utilize data-processing machines for auto-abstracting and auto-encoding of documents and for creating interest profiles for each of the 'action points' in an organization. Both incoming and internally generated documents are automatically abstracted, characterized by a word pattern, and sent automatically to appropriate action points."

Yet as management information systems developed starting in the 1960s, and as BI emerged in the '80s and '90s as a software category and field of practice, the emphasis was on numerical data stored in relational databases. This is not surprising: text in "unstructured" documents is hard to process. The emergence of text analytics in its current form stems from a refocusing of research in the late 1990s from algorithm development to application, as described by Prof. Marti A. Hearst in the paper Untangling Text Data Mining:[60]

For almost a decade the computational linguistics community has viewed large text collections as a resource to be tapped in order to produce better text analysis algorithms. In this paper, I have attempted to suggest a new emphasis: the use of large online text collections to discover new facts and trends about the world itself. I suggest that to make progress we do not need fully artificial intelligent text analysis; rather, a mixture of computationally-driven and user-guided analysis may open the door to exciting new results.

Hearst's 1999 statement of need fairly well describes the state of text analytics technology and practice a decade later.

See also

- Concept mining

- Document processing

- Full text search

- List of text mining software

- Market sentiment

- Name resolution (semantics and text extraction)

- Named entity recognition

- News analytics

- Ontology learning

- Record linkage

- Sequential pattern mining (string and sequence mining)

- w-shingling

- Web mining, a task that may involve text mining (e.g. first find appropriate web pages by classifying crawled web pages, then extract the desired information from the text content of these pages considered relevant)

References

Citations

- "Marti Hearst: What is Text Mining?".

- Hotho, A., Nürnberger, A. and Paaß, G. (2005). "A brief survey of text mining". In Ldv Forum, Vol. 20(1), p. 19-62

- Feldman, R. and Sanger, J. (2007). The text mining handbook. Cambridge University Press. New York

- Archived November 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "KDD-2000 Workshop on Text Mining - Call for Papers". Cs.cmu.edu. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

- Archived March 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Hobbs, Jerry R.; Walker, Donald E.; Amsler, Robert A. (1982). "Natural language access to structured text". Proceedings of the 9th conference on Computational linguistics. 1. pp. 127–32. doi:10.3115/991813.991833.

- "Unstructured Data and the 80 Percent Rule". Breakthrough Analysis. August 2008. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

- "Text Data Pre-processing and Dimensionality Reduction Techniques for Document Clustering" (PDF). International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT). 2012-07-01. Retrieved 2019-11-18.

- Antunes, João (2018-11-14). Exploração de informações contextuais para enriquecimento semântico em representações de textos (Mestrado em Ciências de Computação e Matemática Computacional thesis) (in Portuguese). São Carlos: Universidade de São Paulo. doi:10.11606/d.55.2019.tde-03012019-103253.

- Moro, Andrea; Raganato, Alessandro; Navigli, Roberto (December 2014). "Entity Linking meets Word Sense Disambiguation: a Unified Approach". Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 2: 231–244. doi:10.1162/tacl_a_00179. ISSN 2307-387X.

- Chang, Wui Lee; Tay, Kai Meng; Lim, Chee Peng (2017-02-06). "A New Evolving Tree-Based Model with Local Re-learning for Document Clustering and Visualization". Neural Processing Letters. 46 (2): 379–409. doi:10.1007/s11063-017-9597-3. ISSN 1370-4621.

- "Full Circle Sentiment Analysis". Breakthrough Analysis. 2010-06-14. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

- Mehl, Matthias R. (2006). "Quantitative Text Analysis". Handbook of multimethod measurement in psychology. p. 141. doi:10.1037/11383-011. ISBN 978-1-59147-318-3.

- Pang, Bo; Lee, Lillian (2008). "Opinion Mining and Sentiment Analysis". Foundations and Trends in Information Retrieval. 2 (1–2): 1–135. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.147.2755. doi:10.1561/1500000011. ISSN 1554-0669.

- Paltoglou, Georgios; Thelwall, Mike (2012-09-01). "Twitter, MySpace, Digg: Unsupervised Sentiment Analysis in Social Media". ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology. 3 (4): 66. doi:10.1145/2337542.2337551. ISSN 2157-6904.

- "Sentiment Analysis in Twitter < SemEval-2017 Task 4". alt.qcri.org. Retrieved 2018-10-02.

- Zanasi, Alessandro (2009). "Virtual Weapons for Real Wars: Text Mining for National Security". Proceedings of the International Workshop on Computational Intelligence in Security for Information Systems CISIS'08. Advances in Soft Computing. 53. p. 53. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-88181-0_7. ISBN 978-3-540-88180-3.

- Badal, Varsha D.; Kundrotas, Petras J.; Vakser, Ilya A. (2015-12-09). "Text Mining for Protein Docking". PLOS Computational Biology. 11 (12): e1004630. Bibcode:2015PLSCB..11E4630B. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004630. ISSN 1553-7358. PMC 4674139. PMID 26650466.

- Cohen, K. Bretonnel; Hunter, Lawrence (2008). "Getting Started in Text Mining". PLOS Computational Biology. 4 (1): e20. Bibcode:2008PLSCB...4...20C. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0040020. PMC 2217579. PMID 18225946.

- Badal, V. D; Kundrotas, P. J; Vakser, I. A (2015). "Text mining for protein docking". PLOS Computational Biology. 11 (12): e1004630. Bibcode:2015PLSCB..11E4630B. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004630. PMC 4674139. PMID 26650466.

- Papanikolaou, Nikolas; Pavlopoulos, Georgios A.; Theodosiou, Theodosios; Iliopoulos, Ioannis (2015). "Protein–protein interaction predictions using text mining methods". Methods. 74: 47–53. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.10.026. ISSN 1046-2023. PMID 25448298.

- Szklarczyk, Damian; Morris, John H; Cook, Helen; Kuhn, Michael; Wyder, Stefan; Simonovic, Milan; Santos, Alberto; Doncheva, Nadezhda T; Roth, Alexander (2016-10-18). "The STRING database in 2017: quality-controlled protein–protein association networks, made broadly accessible". Nucleic Acids Research. 45 (D1): D362–D368. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw937. ISSN 0305-1048. PMC 5210637. PMID 27924014.

- Liem, David A.; Murali, Sanjana; Sigdel, Dibakar; Shi, Yu; Wang, Xuan; Shen, Jiaming; Choi, Howard; Caufield, John H.; Wang, Wei; Ping, Peipei; Han, Jiawei (2018-10-01). "Phrase mining of textual data to analyze extracellular matrix protein patterns across cardiovascular disease". American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 315 (4): H910–H924. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00175.2018. ISSN 1522-1539. PMC 6230912. PMID 29775406.

- Van Le, D; Montgomery, J; Kirkby, KC; Scanlan, J (10 August 2018). "Risk Prediction using Natural Language Processing of Electronic Mental Health Records in an Inpatient Forensic Psychiatry Setting". Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 86: 49–58. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2018.08.007. PMID 30118855.

- Jenssen, Tor-Kristian; Lægreid, Astrid; Komorowski, Jan; Hovig, Eivind (2001). "A literature network of human genes for high-throughput analysis of gene expression". Nature Genetics. 28 (1): 21–8. doi:10.1038/ng0501-21. PMID 11326270.

- Masys, Daniel R. (2001). "Linking microarray data to the literature". Nature Genetics. 28 (1): 9–10. doi:10.1038/ng0501-9. PMID 11326264.

- Renganathan, Vinaitheerthan (2017). "Text Mining in Biomedical Domain with Emphasis on Document Clustering". Healthcare Informatics Research. 23 (3): 141–146. doi:10.4258/hir.2017.23.3.141. ISSN 2093-3681. PMC 5572517. PMID 28875048.

- Archived October 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "Text Analytics". Medallia. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

- Coussement, Kristof; Van Den Poel, Dirk (2008). "Integrating the voice of customers through call center emails into a decision support system for churn prediction". Information & Management. 45 (3): 164–74. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.113.3238. doi:10.1016/j.im.2008.01.005.

- Coussement, Kristof; Van Den Poel, Dirk (2008). "Improving customer complaint management by automatic email classification using linguistic style features as predictors". Decision Support Systems. 44 (4): 870–82. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2007.10.010.

- Ramiro H. Gálvez; Agustín Gravano (2017). "Assessing the usefulness of online message board mining in automatic stock prediction systems". Journal of Computational Science. 19: 1877–7503. doi:10.1016/j.jocs.2017.01.001.

- Pang, Bo; Lee, Lillian; Vaithyanathan, Shivakumar (2002). "Thumbs up?". Proceedings of the ACL-02 conference on Empirical methods in natural language processing. 10. pp. 79–86. doi:10.3115/1118693.1118704.

- Alessandro Valitutti; Carlo Strapparava; Oliviero Stock (2005). "Developing Affective Lexical Resources" (PDF). PsychNology Journal. 2 (1): 61–83.

- Erik Cambria; Robert Speer; Catherine Havasi; Amir Hussain (2010). "SenticNet: a Publicly Available Semantic Resource for Opinion Mining" (PDF). Proceedings of AAAI CSK. pp. 14–18.

- Calvo, Rafael A; d'Mello, Sidney (2010). "Affect Detection: An Interdisciplinary Review of Models, Methods, and Their Applications". IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing. 1 (1): 18–37. doi:10.1109/T-AFFC.2010.1.

- "The University of Manchester". Manchester.ac.uk. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

- "Tsujii Laboratory". Tsujii.is.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

- "The University of Tokyo". UTokyo. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

- Shen, Jiaming; Xiao, Jinfeng; He, Xinwei; Shang, Jingbo; Sinha, Saurabh; Han, Jiawei (2018-06-27). Entity Set Search of Scientific Literature: An Unsupervised Ranking Approach. ACM. pp. 565–574. doi:10.1145/3209978.3210055. ISBN 9781450356572.

- Walter, Lothar; Radauer, Alfred; Moehrle, Martin G. (2017-02-06). "The beauty of brimstone butterfly: novelty of patents identified by near environment analysis based on text mining". Scientometrics. 111 (1): 103–115. doi:10.1007/s11192-017-2267-4. ISSN 0138-9130.

- Roll, Uri; Correia, Ricardo A.; Berger-Tal, Oded (2018-03-10). "Using machine learning to disentangle homonyms in large text corpora". Conservation Biology. 32 (3): 716–724. doi:10.1111/cobi.13044. ISSN 0888-8892. PMID 29086438.

- Automated analysis of the US presidential elections using Big Data and network analysis; S Sudhahar, GA Veltri, N Cristianini; Big Data & Society 2 (1), 1-28, 2015

- Network analysis of narrative content in large corpora; S Sudhahar, G De Fazio, R Franzosi, N Cristianini; Natural Language Engineering, 1-32, 2013

- Quantitative Narrative Analysis; Roberto Franzosi; Emory University © 2010

- Lansdall-Welfare, Thomas; Sudhahar, Saatviga; Thompson, James; Lewis, Justin; Team, FindMyPast Newspaper; Cristianini, Nello (2017-01-09). "Content analysis of 150 years of British periodicals". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (4): E457–E465. doi:10.1073/pnas.1606380114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5278459. PMID 28069962.

- I. Flaounas, M. Turchi, O. Ali, N. Fyson, T. De Bie, N. Mosdell, J. Lewis, N. Cristianini, The Structure of EU Mediasphere, PLoS ONE, Vol. 5(12), pp. e14243, 2010.

- Nowcasting Events from the Social Web with Statistical Learning V Lampos, N Cristianini; ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST) 3 (4), 72

- NOAM: news outlets analysis and monitoring system; I Flaounas, O Ali, M Turchi, T Snowsill, F Nicart, T De Bie, N Cristianini Proc. of the 2011 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data

- Automatic discovery of patterns in media content, N Cristianini, Combinatorial Pattern Matching, 2-13, 2011

- I. Flaounas, O. Ali, T. Lansdall-Welfare, T. De Bie, N. Mosdell, J. Lewis, N. Cristianini, RESEARCH METHODS IN THE AGE OF DIGITAL JOURNALISM, Digital Journalism, Routledge, 2012

- Circadian Mood Variations in Twitter Content; Fabon Dzogang, Stafford Lightman, Nello Cristianini. Brain and Neuroscience Advances, 1, 2398212817744501.

- Effects of the Recession on Public Mood in the UK; T Lansdall-Welfare, V Lampos, N Cristianini; Mining Social Network Dynamics (MSND) session on Social Media Applications

- Researchers given data mining right under new UK copyright laws Archived June 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- "Licences for Europe - Structured Stakeholder Dialogue 2013". European Commission. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "Text and Data Mining:Its importance and the need for change in Europe". Association of European Research Libraries. 2013-04-25. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "Judge grants summary judgment in favor of Google Books — a fair use victory". Lexology.com. Antonelli Law Ltd. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "A Brief History of Text Analytics by Seth Grimes". Beyenetwork. 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

- Hearst, Marti A. (1999). "Untangling text data mining". Proceedings of the 37th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics on Computational Linguistics. pp. 3–10. doi:10.3115/1034678.1034679. ISBN 978-1-55860-609-8.

Sources

- Ananiadou, S. and McNaught, J. (Editors) (2006). Text Mining for Biology and Biomedicine. Artech House Books. ISBN 978-1-58053-984-5

- Bilisoly, R. (2008). Practical Text Mining with Perl. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-17643-6

- Feldman, R., and Sanger, J. (2006). The Text Mining Handbook. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83657-9

- Hotho, A., Nürnberger, A. and Paaß, G. (2005). "A brief survey of text mining". In Ldv Forum, Vol. 20(1), p. 19-62

- Indurkhya, N., and Damerau, F. (2010). Handbook Of Natural Language Processing, 2nd Edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-8592-1

- Kao, A., and Poteet, S. (Editors). Natural Language Processing and Text Mining. Springer. ISBN 1-84628-175-X

- Konchady, M. Text Mining Application Programming (Programming Series). Charles River Media. ISBN 1-58450-460-9

- Manning, C., and Schutze, H. (1999). Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-13360-9

- Miner, G., Elder, J., Hill. T, Nisbet, R., Delen, D. and Fast, A. (2012). Practical Text Mining and Statistical Analysis for Non-structured Text Data Applications. Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-386979-1

- McKnight, W. (2005). "Building business intelligence: Text data mining in business intelligence". DM Review, 21-22.

- Srivastava, A., and Sahami. M. (2009). Text Mining: Classification, Clustering, and Applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-5940-3

- Zanasi, A. (Editor) (2007). Text Mining and its Applications to Intelligence, CRM and Knowledge Management. WIT Press. ISBN 978-1-84564-131-3