Terraced houses in Australia

Terraced houses in Australia refers almost exclusively to Victorian and Edwardian era terraced houses or replicas almost always found in the older, inner city areas of the major cities, mainly Sydney and Melbourne. Terraced housing was introduced to Australia in the 19th century. Their architectural work was based on those in London and Paris, which had the style a century earlier.[1][2]

Large numbers of terraced houses were built in the inner suburbs of large Australian cities, particularly Sydney and Melbourne, mainly between the 1850s and the 1890s. The beginning of this period coincided with a population boom caused by the Victorian and New South Wales Gold Rushes of the 1850s and finished with an economic depression in the early 1890s. Detached housing became the popular style of housing in Australia following Federation in 1901.

With artificial urban boundaries, new townhouse type developments—often nostalgically evoking old style terraces in a modern style—returned to the favour of local planning offices in many suburban areas. The modern suburban versions of this style of housing are referred to as "town houses". Terraced houses in Australian cities are highly sought after, and due to their proximity to the CBD of the major cities they are often expensive, much like terraces in New York City.[2]

History and description

Terraced housing in Australia ranged from expensive middle-class houses of three, four and five-storeys down to single-storey cottages in working-class suburbs. The most common building material used was brick, often covered with stucco.

Many terraces were built in the "Filigree" style, distinguished through heavy use of cast iron ornament, on balconies and verandahs, sometimes depicting native Australian flora. As many terraces were built speculatively, there are examples of "freestanding" and "semi-detached" terraces which were either intended to have adjoining terraces added.

In the first half of the twentieth-century, terraced houses in Australia fell into disfavour and many became considered slums. In the 1950s, urban renewal programs were often aimed at eradicating them entirely, not infrequently in favour of high-rise development. In recent decades, there has been a very strong revival of interest in terraced houses in inner-city areas, with many examples having been gentrified.

Victoria

Melbourne

Melbourne's flat terrain has produced regular terraced house patterns. The wealth of the gold rush fuelled speculative housing development and also ensured that many terraces were built with ornate and elaborate details in a generally Italianate style, reaching its zenith in the 1880s with what is often referred to as "boom" style.

The generic Melbourne style of terrace is distinguishable from other regional variations. The majority of designers of Victorian terraces in Melbourne made a deliberate effort to hide roof elements with the use of a decorative parapet, often combined with the use balustrades above a subtle but clearly defined eave cornice and a frieze, which was either plain or decorated with a row of brackets (and sometimes additional patterned bas-relief). Chimneys were often tall, visible above the parapet and elaborately Italianate in style.

Individual terraces were designed to be appreciated on their own as much as part of a row. Symmetry was achieved through a central classical inspired pediment or similar architectural feature, balanced by a pair of architectural finial or urns on either side (though these details were subsequently removed on many terraces). The party walls were almost always decorated with corbels (which sometimes depicted heads), and the large wooden entry doors were decorated with stained or etched glass surrounds.

Many Melbourne terraces also featured a unique style of polychrome brickwork,[3] influenced heavily by the early work of local architect Joseph Reed and often highly detailed (though in many terraces this distinctive feature has been later painted or rendered over, although some have since been sandblasted or stripped back).

The Melbourne style incorporated decorative cast iron balconies (of the filigree style). The demand for imported cast iron eventually led to the establishment of local foundries. As a result, Melbourne has more decorative cast iron than any other city in the world.[4] Melbourne style terraces were often set back from the street rather than built to the property line, providing a small front yard. Decorative cast-iron fencing, regularly dispersed with rendered brick piers, was typically used, and the party wall of the end terraces would sometimes, but not always, extend to the property line to join the fence.

History of terraced housing in Melbourne

The earliest surviving terraced house in Melbourne is Glass Terrace, 72–74 Gertrude Street, Fitzroy (1853–54). Royal Terrace at 50–68 Nicholson Street Fitzroy, completed three years later is only slightly younger and is the oldest surviving complete row.

Multi-storey terraced housing became prevalent in the Melbourne suburbs of Middle Park, Albert Park, East Melbourne, South Melbourne, Carlton, Collingwood, St Kilda, Balaclava, Richmond, South Yarra, Cremorne, North Melbourne, Fitzroy, Port Melbourne, West Melbourne, Footscray, Hawthorn, Abbortsford, Burnley, Brunswick, Parkville, Flemington, Kensington and Elsternwick. Free-standing terraces and single-storey terraces can be found elsewhere within 10 kilometres of the Melbourne city centre.

Terraced housing fell out of favour with Melbourne councils and after the First World War some actually sought to ban them completely.[5] The increase of slums in areas of terraced housing saw the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects in 1910 identify the problem as being caused by small inner city allotment sizes. The Housing and Slum Reclamation Act of 1920 shifted the responsibility for slum reclamation to local councils.[6] The consequence was a shift toward larger block sizes and, inevitably, urban sprawl. During the 1920s, many terraced houses in Victoria were converted into flats.

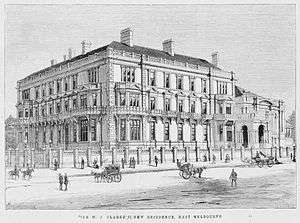

Although Melbourne retains a large number of heritage registered terraces, many rows were substantially affected by widescale slum reclamation programs in favour of the Housing Commission of Victoria's high-rise public housing plans during the 1950s and 60s. Later private development of walk-up flats and in-fill development has further reduced the number of complete rows. However the 1960s saw a new trend of restoration as part of the gentrification of Melbourne's inner suburbs.[7] As a result, streets and suburbs which contain large intact rows of terraced housing are now fairly rare. Suburbs such as Albert Park, Fitzroy, Carlton, Parkville and East Melbourne are now subject to strict heritage overlays to preserve what is left of these streetscapes.

Some of the more notable examples of terraced housing in Melbourne include the heritage registered Tasma Terrace, Canterbury, Clarendon Terrace, Burlington Terrace, Cypress Terrace, Dorset Terrace, Nepean Terrace and Annerly Terrace (East Melbourne), Blanche Terrace, Cobden Terrace, Holyrood Terrace (Fitzroy), Rochester Terrace and the St Vincent Gardens precinct (Albert Park), Royal Terrace, Holcombe Terrace, Denver Terrace, Dalmeny House & Cramond House, and Benvenuta (Carlton), Marion Terrace (St Kilda) and Finn Barr (South Melbourne).

Regional Victoria

Outside of Melbourne in Victoria, the larger cities of Ballarat, Bendigo and Geelong have some scattered historic terraced houses in inner areas, ranging from modest examples to impressive, though generally short, rows. The smaller seaside resort town of Queenscliff has a number of examples from the late 19th century. The towns of Portland and Port Fairy, established early in Victoria's development, have a handful of plain, mainly single-storey, verandah-less early Victorian examples. Other early country towns occasionally have a single example of the same type.

New South Wales

Sydney

%2C_Millers_Point.jpg)

Sydney has some of Australia’s oldest terraced housing. Terraced houses were a feature of the city from around the 1830s. Susannah Place (1844) is one of the earliest still surviving. Others include; Corana and Hygeia, a pair of two-storey Victorian terraced houses built in 1896; Avonmore Terrace (1888), now a boutique hotel. Hortonbridge Terrace, grand triple-storey row of five houses built in 1890. The Horbury Terrace (1836), which is a Georgian terrace that has been reused as offices, and it is listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register.

Due to Sydney's higher density, most terraces tend to be taller than those found in Melbourne, where it is not unusual to find terrace houses of up to four storeys, exemplified by roof features and Dormer windows. Early Georgian style sandstone terraces are found in many of the city's inner suburbs. The terraces of some Sydney suburbs exhibit a distinctly regional variation, with some having Italianate features. The undulating topography of Sydney's inner suburbs means that many of the terraces are typically staggered up hills rather than level or uniform. Sydney terraces were more likely to make a feature of the roof than their Melbourne counterparts, often featuring high-pitched dormer windows, but contrasted with much shorter and plainer chimneys.

Building rules introduced in 1838 required party walls to be raised above the roofline, which helped define the Sydney style and skyline of

terraced suburbs. The terraces often lack a parapet and feature high-pitched roof with dormer windows and attics to make use of the roof space. Sydney terraces were often built right up to the property line; Sydney's narrow streets also make for more intimate street scapes where terraced. As housing developed in Australia, verandas became important as a way of shading the house. From the mid-19th century in particular, as more people became affluent, they built more elaborate homes, and one of the favoured elaborations was the filigree, or screen, of cast iron or wrought iron. This developed to the point where it has become one of the major features of Australian architecture.

In contrast to the British practice of the day, under which dozens or even hundreds of houses were constructed by a developer as a single housing estate, Sydney practice was normally to build a short run of houses, an interesting example being the "Castle Terrace" in Paddington. They feature pitched corrugated iron roofs with round dormer windows, exposed party walls and chimneys with four terracotta pots. The double storey verandahs are rich in iron lacework.

Most Sydney terraces are firmly anchored into solid sandstone, which provided an opportunity to follow the British practice of constructing a

basement storey below street level, reached by a flight of stairs down from the street. Many examples of this are to be found in Paddington. In the suburb of Balmain, there are examples of houses actually constructed from local sandstone, rather than bricks covered with stucco. Another Sydney innovation was the cantilevered verandah which allowed inner city terraces and corner shops to utilise the space above the public footpath and giving the houses a distinctive appearance.[8]

Suburbs where terraced housing is prevalent include those in the inner city such as Alexandria, Annandale, Balmain, Bondi Junction, Camperdown, Chippendale, Darlington, Darlinghurst, Enmore, Erskineville, Glebe, Kirribilli, Leichhardt, Lilyfield, McMahons Point, Marrickville, Millers Point, Newtown, Paddington, Petersham, Potts Point, Pyrmont, Redfern, Rozelle, Stanmore, St Peters, Surry Hills, The Rocks, Woollahra, and Woolloomooloo.

Gallery

house_Erskineville_004.jpg)

.jpg)

Double_Bay_house-3.jpg)

Llandaff_Street_houses.jpg) Bondi Junction

Bondi Junction

Basements are common and are usually accessed from street level

Basements are common and are usually accessed from street level

Regional New South Wales

Outside of Sydney, Newcastle has a fine collection of 1890s terraces. Almost all of them be found in a conservation area just east of the central business district on The Terrace, Wolfe Street, Tyrell Street, Bull Street and Watts Street, including Buchanans Terrace (c. 1890). Campbell Street in Wollongong features the city's only heritage terraced houses. The city of Dubbo has examples of Victorian terraces and semi-detached houses close to the city centre, mostly in the Darling Street area. Bathurst, Orange, and Wagga Wagga have a large number of modest terrace houses.

Queensland

Brisbane

In Brisbane, Queensland, apart from government buildings, stone and attached buildings were deprecated, and in fact legislated against by the Undue Subdivision of Land Prevention Act 1885. Enacted as a public health and anti-slum measure, it set a minimum frontage of about 10 metres for each residential block, thus effectively ending the building of terraces, although a few terraces were built as a single rental project, were not subdivided, and managed to bypass the legislation.

However, only a handful of elaborate heritage listed examples remain, mostly clustered in the Central Business District (The Mansions and Harris Terrace on George Street and Petrie Terrace on Petrie Terrace), and a handful of singular rows in the inner suburbs (Cook's Terrace on Coronation Drive, Milton, and Edmonstone Street in West End).

Most of these examples notably differ in style to terraces in other Australian cities in that as a regional variation, most of them incorporated elements of the Queenslander. In particular high-pitched or hip roof, covered in corrugated galvanised iron is notable as a dominant and practical design element.

Nostalgic replicas became popular in Brisbane in the 1980s and 1990s in mock-Victorian style, in an attempt by developers to appeal to wealthy migrants from interstate. As a result, there are some quite convincing replica Melbourne-style terraces along Gregory Terrace in Brisbane.

South Australia

The planned city of Adelaide, South Australia, has perhaps the most terraced houses of any Australian capital city. Some of the oldest are located on Adelaide's North Terrace. Marine Apartments, in the suburb of Grange, is particularly notable, as it is a large three-storey filigree terrace. It is designed square shape.

Western Australia

In Perth, Western Australia, there are a handful of examples in the inner city and Fremantle's Point Street.

Tasmania

Despite the relatively small size of its major cities in comparison with those on mainland Australia, Tasmania, being one of the oldest European settlements, has a number of fine examples of terraced housing, particularly in inner Hobart. Launceston has some good examples as well, mostly in the central business district and East Launceston, including Alpha Terrace, which has striking similarities to many of the terraces in Sydney's hilly suburbs.

References

- Apperly, Richard; Irving, Robert; Reynolds, Peter (1994). A Pictorial Guide to Identifying Australian Architecture: Styles and Terms from 1788 to the Present. New South Wales: Angus & Robertson.

- Stapleton, Maisy; Stapleton, Ian (1997). Australian House Styles. Mullumbimby, NSW: Flannnel Flower Press.

- William, Logan (1985). The Gentrification of inner Melbourne – a political geography of inner city housing. Brisbane, Queensland: University of Queensland Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-7022-1729-8.

- Cast Iron – a City Dressed in Lace

- Carrol, Brian (1974). Historic Melbourne Sketchbook "Marvellous Melbourne". Rigby Limited. pp. 108–109. ISBN 0-7270-0289-9.

- Lewis, Miles (1995). Melbourne – The City's History and Development. Melbourne: City of Melbourne. p. 93. ISBN 0-949624-88-8.

- THE GENTRIFICATION OF INNER MELBOURNE. A Political Geography of Inner City Housing by LOGAN, William Stewart. University of Queensland Press. 1985

- Howells, T.; Morris, M. (1999). Terrace Houses in Australia. Sydney: Lansdowne Publishing. p. 29.