Tashlikh

Tashlikh (Hebrew: תשליך "cast off") is a customary Jewish atonement ritual performed during the High Holy Days.

| Repentance in Judaism Teshuva "Return" |

|---|

|

Repentance, atonement and higher ascent in Judaism |

| In the Hebrew Bible |

|

|

Altars · Korban Temple in Jerusalem Prophecy within the Temple |

| Aspects |

|

Confession · Atonement Love of God · Awe of God Mystical approach Ethical approach Meditation · Services Torah study Tzedakah · Mitzvot |

| In the Jewish calendar |

|

Month of Elul · Selichot Rosh Hashanah Shofar · Tashlikh Ten Days of Repentance Kapparot · Mikveh Yom Kippur Sukkot · Simchat Torah Ta'anit · Tisha B'Av Passover · The Omer Shavuot |

| In contemporary Judaism |

|

Baal Teshuva movement Jewish Renewal · Musar movement |

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other religions |

|

Related topics |

|

Practice

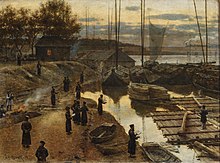

The ritual is performed at a large, natural body of flowing water (e.g., river, lake, sea, or ocean) on the afternoon of Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, although it may be performed until Hoshana Rabbah. The penitent recites a Biblical passage and, optionally, additional prayers. During the Tashlikh prayer, the worshipers symbolically throw their sins into a source of water. There are those who throw small pieces of bread into the water. However numerous sources point out that this is prohibited.

Origin of the custom

Scriptural source

The name "Tashlikh" and the practice itself are derived from an allusion mentioned in the Biblical passage (Micah 7:18-20) recited at the ceremony: "You will cast all their sins into the depths of the sea."[1]

Possible early sources

- Josephus refers to the decree of the Halicarnassians permitting Jews to "perform their holy rites according to the Jewish laws and to have their places of prayer by the sea, according to the customs of their forefathers".[2] However, there was an ancient Jewish custom to site synagogues of the Jewish diaspora on the seashore as an expression of desire to return to Zion.

- The Zohar states that "whatever falls into the deep is lost forever; ... it acts like the scapegoat for the ablution of sins".[3] Some believe that this is a reference to the tashlikh ritual.

Maharil

Most Jewish sources trace a year of the custom back to Yaakov ben Moshe Levi Moelin (d. 1427 in Worms) in his Sefer Maharil. There, he explains the custom as a reminder of the binding of Isaac. He recounts a midrash about that event, according to which Satan threw himself across Abraham's path in the form of a deep stream, in an attempt to prevent Abraham from sacrificing Isaac on Moriah. Abraham and Isaac nevertheless plunged into the river up to their necks and prayed for divine aid, whereupon the river disappeared.[4]

Moelin, however, forbids the practise of throwing pieces of bread to the fish in the river, especially on Shabbat. This would seem to indicate that in his time tashlikh was duly performed, even when the first day of Rosh Hashanah fell on the Sabbath, though in later times the ceremony was, on such occasions, deferred one day.

Shelah

Rabbi Isaiah Horowitz (d. Tiberias, 1630) offers the earliest written source explaining the significance of allusions to fish in relation to this custom. In his eponymous treatise, Shelah (214b), he writes:

- Fish illustrate man's plight, and arouse him to repentance: "As the fishes that are taken in an evil net" (Ecclesiastes 9:12);

- Fish, in that they have no eyelids and their eyes are always wide open, allude to the omniscience of the Creator, who does not sleep.

Ramah

Rabbi Moses Isserles (Krakow, d. 1572), author of the authoritative Ashkenazi glosses to the Shulchan Aruch, explains:[5]

The deeps of the sea allude to the existence of a single Creator that created the world and that controls the world by, for example, not letting the seas flood the earth. Thus, we go to the sea and reflect upon that on New-Year's Day, the anniversary of Creation. We reflect upon proof of the Creator's creation and of His control, so as to repent of our sins to the Creator, and so he will figuratively "cast our sins into the depths of the sea" (Micah 7:18-20).

Opposition to the custom

The Kabbalistic practise of shaking the ends of one's garments at the ceremony, as though casting off the qliphoth, caused many non-kabbalists to denounce the custom. In their view, the custom created the impression among the common people that by literally throwing their sins they might "escape" them without repenting and making amends. The maskilim in particular ridiculed the custom and characterized it as "heathenish". A popular satire from the 1860s was written by Isaac Erter, in his "HaẒofeh leBet Yisrael" (pp. 64–80, Vienna, 1864), in which Samael watches the sins of hypocrites dropping into the river. The Vilna Gaon also did not follow the practice.

Mainstream acceptance today

Today, most mainstream Jewish religious movements view tashlikh as acceptable. It is generally not practised by Spanish and Portuguese Jews, and it is opposed by the Yemenite Dor Daim movement and by a small group of followers of the Vilna Gaon in Jerusalem.

Many Jews in New York City perform the ceremony each year in large numbers from the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges. In cities with few open bodies of water, such as Jerusalem, people perform the ritual by a fish pond, cistern, or mikveh.[6]

References

- Zivotofsky, Ari. "What's the Truth About ... Tashlich?". Jewish Action online. Archived from the original on 2007-08-10.

- Antiquities of the Jews 14:10, § 23

- Zohar, "Vayikra" 101a,b

- "Ask the Rabbi: Shabbat Rosh Hashana 5765". Eretz Hemdah Institute.

- Isserles, Moshe. Torat ha-'Olah. p. 3:56.

- Rabbi Yirmiyahu, Kaganoff. "Appreciating Tashlich". Yeshiva.co. Retrieved 2 September 2013.