Tanbur

The term Tanbur (Persian: تنبور, pronounced [t̪ʰænˈbuːɾ, t̪ʰæmˈbuːɾ])[lower-alpha 1] can refer to various long-necked, string instruments originating in Mesopotamia, Southern or Central Asia.[1] According to the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, "terminology presents a complicated situation. Nowadays the term tanbur (or tambur) is applied to a variety of distinct and related long-necked lutes used in art and folk traditions. Similar or identical instruments are also known by other terms." These instruments are used in the traditional music of Iran, India, Kurdistan, Armenia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkey, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan.[2][3][4]

Man playing a tanbur-family instrument | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Plucked string instrument; fretted lute |

| Related instruments | |

Origins

Tanburs have been present in Mesopotamia since the Akkadian era, or the third millennium BC.[1]

Three figurines have been found in Susa that belong to 1500 BC, and in hands of one of them is a tanbur-like instrument.[5] Also an image on the rocks near Mosul that belong to about 1000 B shows tanbur players.[5]

Playing the tanbur was common at least by the late Parthian era and Sassanid period,[6] and the word 'tanbur' is found in middle Persian and Parthian language texts, for instance in Drakht-i Asurig, Bundahishn, Kar-Namag i Ardashir i Pabagan, and Khosrow and Ridag.[note 1][5]

In the tenth century AD Al-Farabi described two types of tanburs found in Persia, a Baghdad tunbūr, distributed south and west of Baghdad, and a Khorasan tunbūr.[1][5] This distinction may be the source of modern differentiation between Arabic instruments, derived from the Baghdad tunbūr, and those found in northern Iraq, Syria, Iran, Sindh and Turkey, from the Khorasan tunbūr.[1]

The Persian name spread widely, eventually taking in Long-necked string instruments used in Central Asian music such as the Dombura and the classical Turkish tambur as well as the Kurdish tembûr.[1][7] Until the early twentieth century, the names chambar and jumbush were applied to instruments in northern Iraq.[1] In India the name was applied to the tanpura (tambura), a fretless drone lute.[1] Tanbur traveled through Al-Hirah to the Arabian Peninsula and in the early Islam period went to the European countries. Tanbur was called 'tunbur' or 'tunbureh/tunbura' in Al-Hirah, and in Greek it was named tambouras, then went to albania as tampura, in Russia it was named domra, in Siberia and Mongolia as dombra, and in Byzantine Empire was named pandura/bandura. It travelled through Byzantine Empire to other European countries and was called pandura, mandura, bandura, etc.[5]

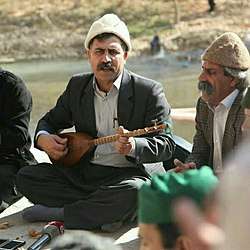

Later the Iranian (Kurdish) tanbur became associated with the music of the Ahl-e Haqq, a primarily Kurdish ghulat religious movement similar to a Sufi order, in Kurdish areas and in the Lorestān and Sistan va Baluchestan provinces of Iran, where it is called the 'tembûr'.[8]

Types

Iranian Tanbur

Nowadays Kermanshahan tanbur (or Kurdish tanbur or tembûr or tanboor or tanbour) is played all over Iran, and that is what is called just "tanbur" in Iran nowadays. Iranian tanbur is mainly designed in Kermanshahan (about Kermanshah Province), Kurdistan Province and Lorestan. Kermanshahan tanburs are more famous and accepted and are specially designed in Kermanshah's Goran Region and Sahneh.[5] The tanbur is currently the musical instrument used in Ahl-e Haqq rituals, and practitioners venerate tembûrs as sacred objects.[7]

There is also a Taleshi tanbur in small region Talesh in the north of Iran, and Tanburak (Tanburg) in Balochistan in the southeast of Iran.[9] But Kermanshahan tanbur is the main and the most famous tanbur in Iran.[5][10]

The Iranian tanbur has a narrow pear-shaped body that normally is made with 7 to 10 glued together separate ribs. Its soundboard is usually made of mulberry wood and some patterned holes are burned in it. The long neck is separate, and has three metal strings that the first course is double. The melody is played on the double strings with a unique playing technique with three fingers of the right hand. Iranian tanbur is associated with the Kurdish Sufi music of Western Iran.[2]

It measures 80 cm in height and 16 cm in breadth.[8] The resonator is pear-shaped and made of either a single piece or multiple carvels of mulberry wood.[8] The neck is made of walnut and has fourteen frets, arranged in a semi-tempered chromatic scale.[8] It has two steel strings tuned in fifth, fourth, or second intervals.[7][8] The higher string may be double-coursed.[7][8]

Central Asia

- The Afghan tanbur (or tambur) is played mainly in the North of Afghanistan, in Mazar Sharif and Kabul. Afghan tanbur used to have a wide, hollow neck and gourd-like body, but nowadays they seem to resemble more the Herati dutar, but its body contour is rounder, and the neck is hollow. It is similar to the Tajik setor. The body is made from one piece of (mulberry) wood, and the neck is separate, and the neck usually has some decoration. It has 3 courses(either single or double) of metal strings. The Afghan tanbur is played in the same style as the normal tanbur and sitar, with a wire finger plectrum. The music can be accompanying singing and dancing, or (more rarely) playing classical ghazals.[3] The Afghan tanbur has sympathetic strings.[11]

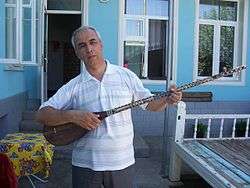

- The Tajik/Uzbek tanbur has four metal strings that run over a small loose bridge to a bit of wood at the edge of the body. It is always played with a wire plectrum on the index-finger. Its body is carved from a hollowed out piece of mulberry wood, and the front is made from mulberry. Its neck is often decorated with inlay bone or white plastic.[3] It can also be played with a bow.[12]

- The Uyghur tembor is played in Sinkiang. Its neck is very long and has five friction pegs. It has five metal strings that are in fact three courses, both first (fingered) and 3rd are double.[3]

Turkish tanbur

- The Turkish tanbur (or Tambur or Turkish tambur) has a very long thin neck and its body is made of about 20 to 25 thin wooden ribs in a very round shape. It has six (three pairs of) metal strings.[2]

- The yaylı tanbur is also played in Turkey.[2] Derived from the older plucked tanbur, it has a long, fretted neck and a round metal or wooden soundbox which is often covered on the front with a skin or acrylic head similar to that of a banjo.

Other plucked string instruments

- Kazakhstan's National instrument the dombra (or dombyra or dombira or dombora) looks quite similar to the dutar although it is made of staves, and it has a flat peghead instead of a neck extension.[3]

- The Afghanistan dambura is mainly played in the North of Afghanistan. It has two slightly different kinds: the Turkestani dambura and the Badachstan dambura.

- Turkestani dambura is fretless, and has two gut or nylon strings fixed to T-shaped flat pegs, and run over a small wooden bridge to a pin at the end of the body.[3]

- The Badachstan dambura is similar to the Turkestani dambura, but it is a bit smaller, and the neck and body are carved from one single piece of (usually mulberry) wood.[3]

- The Punjabi tanburag is a long-neck lute with a big bowl, and has three metal strings, called tanburag [tanboorag] or dhambura, but also called damburo, or kamach(i).[3]

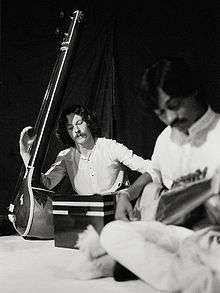

- The Indian Tanpura (tanpura, tamboura or taanpura or tanipurani) is found in different forms and in many places even as electronic tanpura.

- The Shirvan tanbur has a pear-shaped form and belongs to the same family of instruments as the saz. The total length of the tanbur is 940 mm. The length of the body is 385 mm, the width is 200 mm and the height is 135 mm. The length of the neck is 340 mm, and the length of the head is 120 mm. The Shirvan tanbur ranges from the "do" of the first octave to the "mi" of the second octave.

- The Pamiri tanbur is considered to be a more solemn instrument. Its tone is deeper and its tuning more complex than that of the rubab. The tanbur is 80–85 cm in length, and is carved from the trunk of a mulberry or apricot tree. Its sounding board is made of goat or sheep skin. Its unfretted fingerboard has a hollow to create a more powerful voice, and its top is shaped like a half moon. It has seven nylon strings and an eight-string, which duplicates the highest note.[13]

- Similar instruments include the Tamburica (Tamboura or tamburrizza), and the Ukrainian bandura. The Greek tambouras is a long-neck fretted instrument of the lute family, similar to the Turkish saz and the Persian tanbur.

Furthermore, the fretted Tanbur influenced the design of many instruments other than those above, notably;

- The baglama (saz) is found in the Caucasus, Iran, Turkey, northern Syria, western Iraq, and Southeast Europe.[1] In Turkey, the terms bağlama and saz both refer to a long-necked lute used in folk music.[1] Closely related are the Greek bouzouki and the buzuq, an instrument found in urban areas such as Baghdad, Damascus, and Beirut.[1]

- The dutar and setar, found in Iran and Central Asia, are derived from the Khorosanian tunbūr.[1]

- Tamburica or Tamboura (Bosnian: Tamburica, Bulgarian: Тамбура, Croatian: Tamburica, Serbian: Тамбурица, meaning "little Tamboura"; Hungarian: Tambura; Greek: Ταμπουράς, sometimes written tamburrizza) refers to any member of a family of long-necked lutes popular in the Balkans, particularly Hungary, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Serbia (especially Vojvodina), North Macedonia where it is an essential instrument to the Macedonian folklore, alongside the kaval and the bagpipe, Slovenia, Croatia (especially Slavonia). It is also known in Burgenland. All took their name and some characteristics from the Persian tanbur but also resemble the mandolin, in that its strings are plucked and often paired. The frets may be moveable to allow the playing of various modes.

Other instruments

The name also came to apply to several other instruments of different classes including:

- Drums such as the tabor and tambourine.[14]

- The tanbūra (lyre) is a bowl lyre of the Middle East and East Africa. It takes its name from the Persian tanbur via the Arabic tunbur (طنبور), though this term refers to long-necked lutes.[15] The instrument plays an important role in zār rituals.[15] The instrument probably originated in Upper Egypt and the Sudan [15] and is used in the Fann At-Tanbura in the Persian Gulf Arab states.

See also

- Dombra

- Kurdish music

- Balochi music

- Turgun Alimatov

- Category:Eastern lutes players

- Pandura

Notes

- Also variously spelt, romanized or translated as: Tanbūr, Tambur, Tembur, Tanbuur, Tampur, Tempur, Tanbura, Tampolles, Tanpura, Tanpenes, Tembûr, Tambura, Tamboura, Tanboor, Tanbour, Turunbo, Tænbur, Tenbur, Tənbur, Tänbur, Tanbo'er, etc.

References

- Scheherezade Qassim Hassan; Morris, R. Conway; Baily, John; During, Jean (2001). "Tanbūr". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. xxv (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. pp. 61–62.

- "ATLAS of Plucked Instruments - Middle East". ATLAS of Plucked Instruments. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- "ATLAS of Plucked Instruments - Central Asia". ATLAS of Plucked Instruments. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2013.

- McCollum, Jonathan (2014). "Tambur(iv) [tampur, tanbur, tanpur]." New Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Second Edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743391.

- "تنبور (یا تمبور/ طنبور)". Encyclopaedia Islamica. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- Jean During, Spirit of Sounds : The Unique Art of Ostad Elahi (1895-1974), ASSOCIATED UNIVERSITY PRESS, ISBN 978-0-8453-4884-0, ISBN 0-8453-4884-1

- Shiloah, Amnon (2001). "Kurdish music". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. xiv (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. p. 40.

- Scheherezade Qassim Hassan; Morris, R. Conway; Baily, John; During, Jean (2001). "Tanbur". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. xxv (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. pp. 61–62.

- "Grup Müştak Hıdırellez 2016" (PDF). alevibektasikulturenstitusu.de. Alevitisch-Bektaschitisches Kulturinstitut E. V. 8 May 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

In the Northern parts of Iran, Northwest of Gilan province, a version of Tanbour called Taleshi Tanbour is played in Taleshi people Rituals.

- درویشی, محمدرضا (۱۳۸۳). "تنبور - کرمانشاهان (Tanbur-kantot-Kermanshahan)". دایرةالمعارف سازهای ایران. تهران: موسسه فرهنگی هنری ماهور. pp. 95, 213, 303. ISBN 9646409458. Check date values in:

|year=(help) - "Instruments, Tanbur". akdn.org. Aga Khan Development Network. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- Cerys Matthews, BBC Radio 6, 22 June 2018

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-07-06. Retrieved 2010-06-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Chambers Twentieth Century Dictionary 1977, "Tambourine".

- Poché, Christian (2001). "Tanbūra". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. xxv (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. pp. 62–63.

External links

- Atlas of Plucked Instruments: Central Asia

- Analysis and Physical Modeling of Tanbur from the Helsinki University of Technology (Turkish Tambur)

.jpg)