Qanbūs

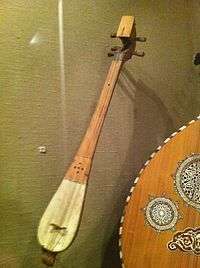

A qanbūs or gambus (Arabic: قنبوس) is a short-necked lute that originated in Yemen[1] and spread throughout the Arabian peninsula. Sachs considered that it derived its name from the Turkic komuz, but it is more comparable to the oud.[2] The instrument was related to or a descendant of the barbat.[3] It has twelve nylon strings that are plucked with a plastic plectrum to generate sound, much like a guitar. However, unlike a guitar, the gambus has no frets. Its popularity declined during the early 20th century reign of Imam Yahya; by the beginning of the 21st century, the oud had replaced the qanbūs as the instrument of choice for Middle-Eastern lutenists.

Yemen migration saw the instrument spread to different parts of the Indian Ocean. In Muslim Southeast Asia (especially Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei), called the gambus, it sparked a whole musical genre of its own. Today it is played in Johor, South Malaysia, in the traditional dance Zapin and other genres, such as the Malay ghazal and an ensemble known as kumpulan gambus ("gambus group"). Kumpulan gambus can also be found active in Sabah, especially in the Bongawan district of East Malaysian Borneo. In the Comoros it is known as gabusi,[4] and in Zanzibar as gabbus.

In Yemen and Oman

The qanbus is a traditional instrument from Yemen carved from a single block of wood. It is also played in Oman, where it is called gabbus. The lower half of the top is covered in skin, and the upper half has a wooden soundboard, often with small soundholes. It has a floating bridge, a sickle-shaped pegbox and usually 7 nylon or gut strings in 4 courses, with the lowest course single. There also exist 3 course versions, with 6 or 5 strings, though these are less common. [5][6]

In East Africa

In Kenya and Tanzania, a related instrument is played called the Kibangala. It is built and strung in the same way as the Qanbus. In the Comoros islands, a related instrument called the Gambusi is played, which is built in the same way but often has a flat-shaped pegbox, rather than the sickle-shape, and sometimes has a differently shaped soundbox. Both usually have 4 courses of strings, which can be double or single. [7][8][9]

In Malaysia and Indonesia

in Malaysia and Indonesia, a large group of related instruments are built and played in much the same way. These include the gambus panting and gambus melayu. These are built the same way, but can have either a skin top or a wooden soundboard. They can have 3, 4 or 5 courses of strings. In Malaysia, the word gambus can also refer to the oud, so to avoid confusion, various descriptors are used in the names. The dambus is a related instrument which always has a wooden soundboard and a carved deer on the end of the pegbox.

Some modern luthiers in Malaysia and other countries have begun to made hybrid instruments, combining the Gambus or Dambus with the Oud or other instruments.[10][11][12]

Similar instruments

- Gittern - a medieval European instrument built in the same way, but with a completely wooden soundboard.

Sources

- Urkevich, Lisa (2014). Music and Traditions of the Arabian Peninsula: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar. Routledge. p. 341.

- The gambus (lutes) of the Malay world: its origins and significance in zapin Music, Larry Hilarian, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 06 Jul 2004

- Hiliarian, Larry Francis. "Documentación y rastreo histórico del laúd malayo (gambus) [translation: Documentation and historical tracking of the Malayan lute (gambus)]". scielo.org. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

El gambus melayu que ahí llegó podría ser, o bien un descendiente directo del barbat persa, o del qanbus yemenita, que a su vez evolucionó del barbat.[translation: The melayu gambus that arrived there could be either a direct descendant of the Persian barbat, or the Yemenite qanbus, which in turn evolved from the barbat.]

- Simon Broughton; Mark Ellingham; Richard Trillo (1999). World Music: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. Rough Guides. pp. 505–. ISBN 978-1-85828-635-8. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- https://atlasofpluckedinstruments.com/middle_east.htm#yemen

- http://inthegapbetween.free.fr/pierre/webpage_HTML1/GAMBUS_PROJECT_page.htm

- https://atlasofpluckedinstruments.com/africa.htm#east

- https://stringedinstrumentdatabase.aornis.com/j.htm

- http://inthegapbetween.free.fr/pierre/webpage_HTML1/GAMBUS_PROJECT_page.htm

- https://atlasofpluckedinstruments.com/se_asia.htm#malaysia

- https://stringedinstrumentdatabase.aornis.com/g.htm

- http://inthegapbetween.free.fr/pierre/webpage_HTML1/GAMBUS_PROJECT_page.htm

References

- Poche, Christian. "Qanbūs". Grove Music Online (subscription required). ed. L. Macy. Retrieved on August 15, 2007.

- Gambus - Musical instruments of Malaysia

- Charles Capwell, Contemporary Manifestations of Yemeni-Derived Song and Dance in Indonesia, Yearbook for Traditional Music, Vol. 27, (1995), pp. 76–89 reg

Kinzer, Joe. "The Agency of a Lute: Post-Field Reflections on the Materials of Music." Blog post. Ethnomusicology Review: Notes from the Field. UCLA,2016.

External links

French anthropologist, Jean Lambert, singing a Sana’ani song using Qanbūs and other Yemeni musical instruments on YouTube

Further reading

- Qanbus, Kigangala, & Gabusi: A Portfolio. Monoxyle Lutes/Index v.21 March 2016