Tamar Bridge

The Tamar Bridge is a major road bridge over the River Tamar between Saltash, Cornwall and Plymouth, Devon in southwest England. It is 335 metres (1,099 ft) long, running adjacent to the Royal Albert Bridge, and part of the A38, a main road between the two counties.

Tamar Bridge | |

|---|---|

View from the Royal Albert Bridge, 2009 | |

| Coordinates | 50°24′29.29″N 04°12′12.20″W |

| Carries | A38 trunk road |

| Crosses | River Tamar |

| Locale | Saltash – Plymouth in southwest England |

| Website | Official website |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Suspension bridge |

| Longest span | 335 metres (1,099 ft)[1] |

| History | |

| Constructed by | Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company |

| Construction start | July 1959 |

| Construction end | October 1961 |

| Opened | 26 April 1962 |

| Rebuilt | 1999–2001 |

| Statistics | |

| Toll | £2.00 (cars) eastbound only |

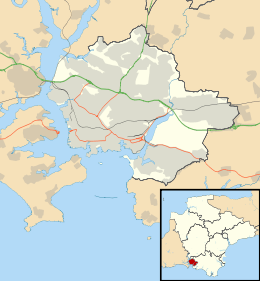

Tamar Bridge Location near Plymouth | |

During the 20th century, there was increasing demand to replace or supplement the Saltash and Torpoint ferries, which could not cope with the rise in motor traffic. The Government refused to prioritise the project, so it was financed by Plymouth City Council and Cornwall County Council. Construction was undertaken by the Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company and began in 1959. It was unofficially opened in October 1961, with a formal presentation by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother in April 1962. A reconstruction of the bridge began in 1999 after it was found to be unable to support a European Union requirement for goods vehicle weights. The work involved building two new parallel decks while the original construction was completely rebuilt. The project was completed in late 2001 and formally opened by Princess Anne in April 2002. The extra decks have remained in use, increasing the bridge's capacity.

The bridge is tolled for eastbound travel, with a discount available via an electronic payment scheme. It has become a significant landmark in Plymouth, Saltash and the surrounding area, and used on several occasions for protests or to highlight the work of charities and fundraisers.

Location

.jpg)

The bridge runs over the River Tamar from near Wearde, Saltash in the west to Riverside, Plymouth in the east. It has a central span of 335 metres (1,099 ft) and two side spans of 114 metres (374 ft).[1] It is part of the A38, a major cross-country road that runs across Cornwall and Devon, and lies immediately north of the Royal Albert Bridge, a significant railway bridge designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel that opened in 1859. Both bridges are north of the Hamoaze, the estuary that the Tamar feeds into, and the Torpoint Ferry.[2]

The bridge is owned and maintained by the Tamar Bridge and Torpoint Ferry Joint Committee, a conglomerate between Plymouth City Council and Cornwall County Council.[1] It has a main span of three lanes, which use a tidal flow arrangement to maximise traffic flow at rush hour, and two outer lanes. The north of these is used as a local access route from Saltash, while the south is used by cyclists and pedestrians but could be converted to meet future vehicle demand if alternatives for pedestrians and bicycles were provided, a dedicated ferry, shuttle bus, cable car or bridge have been considered.[1]

Tolls

The current tolls are £2.00 for cars, and £4.90, £8.00 and £11.00 for 2, 3 and 4-axle goods vehicles over 3.5 tonnes respectively. An electronic device called the Tamar Tag can be affixed to a vehicle window, which allows the driver to travel at half-fare. Tolls are only payable when travelling eastbound from Saltash to Plymouth.[3]

There is no charge for pedestrians, cyclists and motorcycles.[3] Disabled drivers can apply for concessions online or via an office next to the Torpoint Ferry.[4]

Construction

Requirement

For centuries, road users wishing to go from Saltash to Plymouth had two main choices. Travel by coach involved a long detour north either to Gunnislake New Bridge (a one-lane bridge constructed in 1520), or other bridges further north along the Devon – Cornwall border.[5] The alternative was to catch a ferry across the Tamar. The Torpoint Ferry had been running successfully since 1791 (and is still in active service)[6][7] while the Saltash Ferry ran near to the bridge's present location.[8] While popular, the ferries did not have sufficient capacity by the 20th century to cater for motor traffic.[9] The idea for a fixed crossing across the Tamar had been floated around since the early 19th century,[10] and proposals had been discussed in Parliament as early as 1930.[11]

In 1950, Cornwall County Council and Plymouth City Council discussed the feasibility of building a road bridge. The government was unenthusiastic about the idea, as they did not believe it was financially viable and there were more urgent projects in post-war Britain. After being rebuked, both councils agreed to self-fund the entire project, which would be paid for in tolls.[10] The scheme received Royal Assent in July 1957.[12] Invitations to tender were sent on 4 March 1959, and a proposal from the northeast England-based Cleveland Bridge & Engineering Company was accepted on 9 June.[10]

Building

Preparatory work on the bridge started in July 1959. The bridge was built using suspended construction, which involved building two 67 metres (220 ft) concrete towers with support cables over these. Hangers were attached to these cables and the road deck was transported by barge and lifted into place.[13] Cleveland Bridge and Engineering later used the same technique to construct the first Severn Bridge.[14]

The central span of the bridge was 1,848 feet (563 m). The support cables were both 2,200 feet (670 m) long, with a combined weight of 850 tons. They were constructed for Cleveland Bridge and Engineering by British Ropes Ltd.[15] The deck was made out of a concrete base covered with 20-millimetre (0.79 in) steel plates approx and 200-millimetre (7.9 in) of standard road tarmac.[16] The roadway catered for three lanes of traffic and was designed to be 33 feet (10 m) wide, with an additional 6 feet (1.8 m) for pedestrians either side of the bridge.[15] It could support an estimated capacity of 20,000 vehicles a day,[15] with a maximum individual vehicle weight of 38 tons.[16] Bridge materials had a similar colour to the Royal Albert Bridge, which it runs parallel to.[17]

The bridge was unofficially opened at 6am on 24 October 1961, when the construction barriers were removed.[15] It was formally opened by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother on 26 April 1962.[18]

The total cost of the bridge was £1.8 million (now £40 million).[15] It was the first major suspension bridge to be constructed in the UK after World War II, and the longest suspension bridge in Britain.[2]

Operation

The initial toll for cars was 3s (15p) for a single journey across the bridge, or 4/6 (22½p) for a return, while for lorries it was 14s (70p) and £1 respectively.[15] The Saltash Ferry closed, but the Torpoint Ferry remained in operation; management of the ferry and the bridge is shared so the two crossings are not in direct competition with each other.[19]

By 1979, the toll had risen to 30p for a single car journey.[20] It had risen again to £1 by 1995,[21] which remained in place until 2010, when they were increased to £1.50.[22] On 19 November 2019 the new standard toll was set at £2.00.[23]

In 1961, approximately 4000 vehicles used the Tamar Bridge each day.[16] This significantly increased in the following decades; in 1998 the hourly rate during the morning rush hour was 2500 vehicles. The average weekday saw 38,200 vehicles cross the bridge and the summer weekday flow was 42,900. Conversely, the Torpoint ferry link could transport a maximum of 300 vehicles per hour.[24]

Widening and strengthening

Though the original bridge was designed for 38-ton vehicles, when it was inspected around 1995 it was found unable to comply with a European Union directive for supporting vehicles up to 40 tons,[25] and would only be able to support 17-ton vehicles.[26] A feasibility study was carried out for a new Tamar Crossing in 1991,[27] but was rejected as the estimated cost would be around £300 million.[26] The existing bridge could not be closed as it was being used by over 40,000 vehicles a day.[28]

The eventual solution was to add two additional orthotropic cantilever lanes either side of the bridge, which traffic could run on while the original road deck was replaced. The work was designed by Hyder Consulting and constructed by the descendent company of Cleveland Bridge that had worked on the original project. Reconstruction started in 1999, and was slightly delayed owing to an influx of tourists travelling to Cornwall to watch the Solar eclipse of 11 August 1999, whose line of totality passed through the county.[28] The new deck contained 82 orthotropic panels, each one measuring 6 metres (20 ft) by 15 metres (49 ft) and weighing 20 tons.[10] Work was completed in December 2001 at a total cost of £34 million; the two additional lanes were retained to increase the bridge's capacity.[28] The completed construction weighed 25 tons less than the original bridge.[16]

The Tamar Bridge was officially reopened by Princess Anne on 26 April 2002, exactly forty years after the initial opening.[29] Traffic was not expected to increase following the expansion of the bridge, as the Saltash Tunnel further west acts as a buffer for capacity.[28] It was the world's first suspension bridge to be widened using cantilevers, and the world's first suspension bridge to be widened and strengthened while remaining open to traffic. The project won the British Construction Industry Civil Engineering Award for 2002, the Historic Structures category (30 years or older) of the Institution of Civil Engineers Awards 2002, and was one of eight finalists for the Prime Minister's Better Public Building Award 2002.[30]

Bill Moreau, chief engineer of the New York State Bridge Authority, was impressed by the project. He visited the bridge shortly after its reconstruction, and hoped that similar methods could be used on numerous ageing bridges in New York, such as the George Washington Bridge.[31]

The bridge capacity is around 1,800 vehicles per hour per lane over each main and added decks:[32]

- 3,600 per hour for the combined two peak direction main deck lanes

- 1,800 per hour for the off peak direction main deck lane

- 1,800 per hour for the eastbound local link from Saltash over the northern cantilever lane

- southern cantilever lane used for pedestrians and cycles

The toll booth capacity in the eastbound direction only as operated in 2013 was 4,200 vehicles per hour and not considered to be constraining the route flow even though it's less than the potential eastbound 5,400 vehicles per hour from two main lanes and Saltash local.

The actual capacity of the link has other constraints:

- 3,600 vehicles per hour of the A38 dual carriageway in Plymouth east of the bridge and toll booths

- the Plymouth Pemros Road roundabout has an evening peak westbound capacity of 3,400 vehicles per hour, below the combined 3,600 of the two allocated main bridge lanes

- the Plymouth Pemros Road roundabout has a morning peak westbound capacity determined by the two into one lane merge on exiting the roundabout and the need to give way to busses

- 3,600 peak direction and 1,800 off peak to the west of the bridge in the Saltash Tunnel

- the two into one lane merge on the eastbound approach during pm peaks when one bridge lane is allocated constrains that flow to below 1,800 vehicles per hour of the single bridge lane used

Legacy

.jpg)

The Tamar Bridge is a recognisable symbol of the local area, as well as a main road connection between Cornwall and the rest of England. A supporter for devolution in Cornwall, following that of Wales and Scotland, has said the county is "a bit like a parallel universe over the Tamar Bridge".[33]

In March 1998, after the closure of Europe's last tin mine at South Crofty in Cornwall (which later reopened for a period, and subsequently closed), the Cornish Solidarity Action Group (CSAG) encouraged commuters to pay the then-£1 toll in pennies. The group thought this would slow down collection of tolls and cause widespread congestion across the local area. The CSAG believed Cornwall should receive similar subsidies to South Wales and Merseyside, which were receiving regeneration grants from the government.[34]

On 23 January 2004 four protesters climbed onto the gantry over the Tamar Bridge to highlight the work of the group Fathers 4 Justice who promote the rights of fathers in child custody disputes. The protest caused rush-hour tailbacks on both sides of the bridge.[35] Charges against the protesters were later dropped after it was felt there would not be a realistic chance of conviction.[36]

In 2012 local councillors complained when the Olympic organising committee declined to run the Olympic Torch across the Tamar Bridge in the lead-up to the Olympics in London. One councillor said the handover should have been "one of the iconic moments of the whole torch relay in Cornwall". The official organisers said it was not practical to do so as it would involve closing the bridge.[37]

References

Citations

- Plymouth & Cornwall 2013, p. 15.

- Brown 2007, p. 1.

- "Tamar Bridge Tolls". Tamar Crossings. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Mobility Scheme". Tamar Crossings. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- Otter 1994, p. 32.

- Otter 1994, p. 33.

- "Torpoint Ferry". Tamar Crossings. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- Tait, Derek (2014). The River Tamar Through Time. Amberley Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-445-62593-5.

- "River Tamar Crossing (report)". Hansard. 27 October 1954. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Brown 2007, p. 3.

- "River Tamar Bridge". Hansard. 29 April 1930. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Royal Assent". Hansard. 31 July 1957. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Brown 2007, pp. 3,4.

- Brown 2007, p. 4.

- "Road Bridge over Tamar opened". The Times. 25 October 1961. p. 5. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Brown 2007, p. 6.

- Brown 2007, p. 5.

- "Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother cutting the tape to open the Tamar Bridge linking Devon and Cornwall yesterday". The Times. 27 April 1962. p. 6. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Brown 2007, p. 2.

- "Toll Bridges and Tunnels". Hansard. 4 December 1979. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Toll Bridges". Hansard. 19 December 1995. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Tamar Bridge toll goes up to £1.50". BBC News. 15 March 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- McDonald, Gayle (19 November 2019). "Tamar Bridge and Torpoint Ferry tolls rise today". Plymouth Herald. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- "Select Committee on the Tamar Bridge Bill". 9 July 1998. Archived from the original on 22 February 2001.

- "Tamar Bridge Bill". Hansard. 11 June 1998. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Brown 2007, p. 8.

- "Projects and Contracts". Hansard. 2 February 1994. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Brown 2007, p. 9.

- "Today's royal engagements". The Times. 26 April 2002. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- Brown 2007, p. 10.

- "New York inspired by Tamar Bridge". BBC News. 4 January 2002. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- Plymouth & Cornwall 2013, p. 20-24.

- Barford, Vanessa (18 August 2014). "Scottish independence: Is Cornwall more like Scotland than England?". BBC News. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Cornwall demands economic help". BBC News. 14 March 1998. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Man's bridge protest continues". BBC News. 24 January 2004. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "Tamar Bridge protester walks free". BBC News. 6 April 2005. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- "London 2012: Cornwall Olympic torch Tamar Bridge dismay". BBC News. 17 May 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

Sources

- Otter, R. A. (1994). Southern England : Civil engineering heritage. Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-727-71971-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, A.J. (2007). The Tamar Bridge (PDF) (Report). University of Bath.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- River Tamar Crossings Study (PDF) (Report). Plymouth City Council, Cornwall County Council. July 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tamar Bridge. |

- Official Tamar Bridge website

- Official Torpoint Ferry website

- Archive film showing the original construction

- Tamar Bridge at Structurae

UK legislation

- Text of the Tamar Bridge Act 1998 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.