Synagogue architecture

Synagogue architecture often follows styles in vogue at the place and time of construction. There is no set blueprint for synagogues and the architectural shapes and interior designs of synagogues vary greatly. According to tradition, the Divine Presence (Shekhinah) can be found wherever there is a minyan, a quorum, of ten. A synagogue always contains an ark, called aron ha-kodesh by Ashkenazim and hekhal by Sephardim, where the Torah scrolls are kept.

.jpg)

Blueprint for synagogues

The ark may be more or less elaborate, even a cabinet not structurally integral to the building or a portable arrangement whereby a Torah is brought into a space temporarily used for worship. There must also be a table from which the Torah is read. The table, called bimah by eastern Ashkenazim, almemmar (or balemmer) by Central and Western Ashkenazim and tebah by Sephardim, where the Torah is read (and from where the services are conducted in Sephardi synagogues) can range from an elaborate platform integral to the building (many early modern synagogues of central Europe featured bimahs with pillars that rose to support the ceiling), to elaborate free-standing raised platforms, to simple tables. A ner tamid, a constantly lit light as a reminder of the constantly lit menorah of the Temple in Jerusalem. Many synagogues, mainly in Ashkenazi communities, feature a pulpit facing the congregation from which to address the assembled. All synagogues require an amud (Hebrew for "post" or "column"), a desk facing the Ark from which the Hazzan (reader, or prayer leader) leads the prayers.

A synagogue may or may not have artwork; synagogues range from simple, unadorned prayer rooms to elaborately decorated buildings in every architectural style.

The synagogue, or if it is a multi-purpose building, prayer sanctuaries within the synagogue, are typically designed to have their congregation face towards Jerusalem. Thus sanctuaries in the Western world generally have their congregation face east, while those east of Israel have their congregation face west. Congregations of sanctuaries in Israel face towards Jerusalem. But this orientation need not be exact, and occasionally synagogues face other directions for structural reasons, in which case the community may face Jerusalem when standing for prayers.

Historically, synagogues were built in the prevailing architectural style of their time and place. Thus, the synagogue in Kaifeng, China looked very like Chinese temples of that region and era, with its outer wall and open garden in which several buildings were arranged.

The styles of the earliest synagogues resembled the temples of other sects of the eastern Roman Empire. The synagogues of Morocco are embellished with the colored tilework characteristic of Moroccan architecture. The surviving medieval synagogues in Budapest, Prague and the German lands are typical Gothic structures.

For much of history, the constraints of anti-semitism and the laws of host countries restricting the building of synagogues visible from the street, or forbidding their construction altogether, meant that synagogues were often built within existing buildings, or opening form interior courtyards. In both Europe and in the Muslim world, old synagogues with elaborate interior architecture can be found hidden within nondescript buildings.

Where the building of synagogues was permitted, they were built in the prevailing architectural style of the time and place. Many European cities had elaborate Renaissance synagogues, of which a few survive. In Italy there were many synagogues in the style of the Italian Renaissance (see Leghorn; Padua; and Venice). With the coming of the Baroque era, Baroque synagogues appeared across Europe.

The emancipation of Jews in European countries and of Jews in Muslim countries colonized by European countries gave Jews the right to build large, elaborate synagogues visible from the public street. Synagogue architecture blossomed. Large Jewish communities wished to show not only their wealth but also their newly acquired status as citizens by constructing magnificent synagogues. Handsome nineteenth synagogues form the period of Jewish imagination stand in virtually every country where there were Jewish communities. Most were built in revival styles then in fashion, such as Neoclassical, Neo-Byzantine, Romanesque Revival Moorish Revival, Gothic Revival, and Greek Revival. There are Egyptian Revival synagogues and even one Mayan Revival synagogue. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century heyday of historicist architecture, however, most historicist synagogues, even the most magnificent ones, did not attempt a pure style, or even any particular style, and are best described as eclectic.

Chabad Lubavitch has made a practice of designing some of its Chabad Houses and centers as replicas of or homages to the architecture of 770 Eastern Parkway.

Central Europe: Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The great exceptions to the rule that synagogues are built in the prevailing style of their time and place are the wooden synagogues of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and two forms of masonry synagogues: synagogues with bimah-support and nine-field synagogues (the latter not totally confined to synagogues).

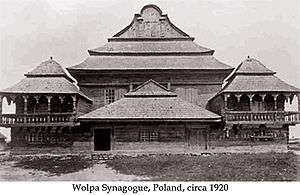

Wooden synagogues

The wooden synagogues were a unique Jewish artistic and architectural form.[1] Characteristic features include the independence of the pitched roof from the design of the interior domed ceiling. They had elaborately carved, painted, domed, balconied and vaulted interiors. The architectural interest of the exterior lay in the large scale of the buildings, the multiple, horizontal lines of the tiered roofs, and the carved corbels that supported them. Wooden synagogues featured a single, large hall. In contrast to contemporary churches, there was no apse. Moreover, while contemporary churches featured imposing vestibules, the entry porches of the wooden synagogues was a low annex, usually with a simple lean-to roof. In these synagogues, the emphasis was on constructing a single, large, high-domed worship space.[2][1][3][4]

According to art historian Stephen S. Kayser, the wooden synagogues of Poland with their painted and carved interiors were "a truly original and organic manifestation of artistic expression—the only real Jewish folk art in history."[5]

According to Louis Lozowick, writing in 1947, the wooden synagogues were unique because, unlike all previous synagogues, they were not built in the architectural style of their region and era, but in a newly evolved and uniquely Jewish style, making them "a truly original folk expression," whose "originality does not lie alone in the exterior architecture, it lies equally in the beautiful and intricate wood carving of the interior."[6]

Moreover, while in many parts of the world Jews were proscribed from entering the building trades and even from practicing the decorative arts of painting and woodcarving, the wooden synagogues were actually built by Jewish craftsmen.[6]

Art historian Ori Z. Soltes points out that the wooden synagogues, unusual for that period in being large, identifiably Jewish buildings not hidden in courtyards or behind walls, were built not only during a Jewish "intellectual golden age" but in a time and place where "the local Jewish population was equal to or even greater than the Christian population.[7]

Synagogues with bimah-support

In the second half of the 16th century masonry synagogues whose interiors present an original structural solution, found in no other kind of building, were constructed in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. These were synagogue halls whose bimah was surrounded by four pillars. Placed upon a podium, connected above by arcading, in one powerful pier, the pillars constituted the bimah-support (or bimah-tower) supporting the vault, consisting of four barrels witl lunettes intersecting at the corners. The bases of the vault-rips rested on the podium or were transmitted through a balustrade, solid or pierced. A small cupola covered the field above the bimah. These cupolas were occasionally significantly lowered in comparison with the remaining fields of vaulting. Thus a kind of inner chapel, built inside the bimah-tower, was created.[8]

One of the first synagogues with a bimah-support was the Old Synagogue (Przemyśl), which was destroyed during World War II. Synagogues with a bimah-tower were built up to the 19th century and the concept was adopted in various Central European countries.[9]

Nine-field synagogues

Around the beginning of the 1630s the first synagogues with nine-field vaulting were constructed. They allowed for much greater halls than hitherto and were also called nine-bay synagogues. The Great Suburb Synagogue in Lviv and the synagogue in Ostroh were erected virtually at the same time (1625 and 1627). In these halls the vaulting rested on four tall pillars and on correspomding wall pilasters. The columns and the pilasters were situated in equal spacing and dividing the roof-area into nine equal fields. In these synagogues the bimah was a free-standing podium or a bower situated within the central field between the pillars.[10]

Egyptian Revival

Egyptian Revival style synagogues were popular in the early nineteenth century. Rachel Wischnitzer argues that they were part of the fashion for Egyptian style inspired by Napoleon's invasion of Europe.[11] According to Carol Herselle Krinsky, they were meant as imitations of the Temple of Solomon and intended by architects and governments to insult Jews by portraying Judaism as a primitive faith.[12] According to Diana Muir Appelbaum, they were expressions of Jewish identity intended to advertise Jewish origins in ancient Israel.[13]

Moorish influence

In medieval Spain (both Al-Andalus and the Christian kingdoms), a host of synagogues were built, and it was usual to commission them from Moorish and later Mudéjar architects. Very few of these medieval synagogues, built with Moorish techniques and style, are conserved. The two best known Spanish synagogues are in Toledo, one known as El Tránsito, the other as Santa María la Blanca, and are now preserved as national monuments. The former is a small building containing very rich decorations; the latter is especially noteworthy. It is based upon Almohad style and contains long rows of octagonal columns with curiously carved capitals, from which spring Moorish arches supporting the roof.

Another significant Mudéjar synagogue is the one at Córdoba built in 1315. As in El Tránsito, the vegetal and geometrical stucco decorations are purely Moorish, but unlike the former, the epigraphic texts are in Hebrew.

After the expulsion from Spain there was a general feeling among wealthy Sephardim that Moorish architecture was appropriate in synagogues. By the mid-19th century, the style was adopted by the Ashkenazim of Central and Eastern Europe, who associated Moorish and Mudéjar architectural forms with the golden age of Jewry in Al-Andalus. As a consequence, Moorish Revival spread around the globe as a preferred style of synagogue architecture, although Moorish architecture is by no means Jewish, either in fact or in feeling. The Alhambra has furnished inspiration for innumerable synagogues, but seldom have its graceful proportions or its delicate modeling and elaborate ornamentation been successfully copied.

Moorish style, when adapted by the Ashkenazi was believed to have been a reference to the Golden Age of Spanish Jewry,[14] it was not the primary intention of the Jews and architects who chose to build in the Moorish style.[15] Rather, the choice to use the Moorish style was reflective of pride in their Semitic or oriental heritage.[15] This pride in their heritage and understanding of Jews as "semitic" or "oriental" led architects like Gottfried Semper (Semper Synagogue Dresden, Germany) and Ludwig Förster (Tempelgasse or Leopoldstädter Tempel, Vienna, Austria and Dohány Street Synagogue, Budapest, Hungary) to build their synagogues in the Moorish style.[16] Moorish Style remained a popular choice for synagogues throughout the rest of the 19th and early 20th century.

Modern synagogue architecture

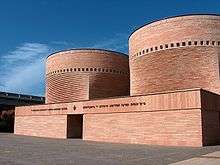

_ShiftN_cropped.jpg)

In the modern period, synagogues have continued to be built in every popular architectural style, including Art Nouveau, Art Deco, International style, and all contemporary styles. In the post-World War II period "a period of post-war modernism," came to the fore, "characterized by assertive architectural gestures that had the strength and integrity to stand alone, without applied artwork or Jewish iconography."[17] A notable work of Art Nouveau, pre-World War I Hungarian synagogue architecture is Budapest's Kazinczy Street Synagogue.[18] In the UK, synagogues built in the early 1960s, such as a Carmel College (Oxfordshire) in the UK, designed by the British architect,Thomas Hancock,[19] were decorated with the stained glass of windows of Israeli artist, Nehemia Azaz. The stained glass windows were praised by art and architecture scholar Nikolaus Pevsner as using "extraordinary technique with rough pieces of coloured glass like crystals"[20] and by Historic England as "brilliant and innovative artistic glass".[19]

The interior

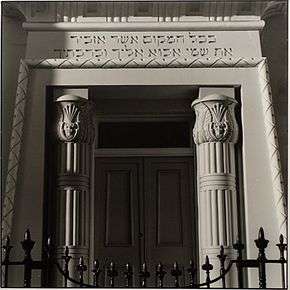

The most common general plan for the interior of the synagogue is an Ark at the eastern end opposite the entrance, and with an almemar or pulpit. In older or Orthodox synagogues with separate seating, there may be benches for the men on either side, and a women's gallery reached by staircases from the outer vestibule. Variations of this simple plan abound: the vestibule became larger, and the staircases to the women's gallery were separated from the vestibule and given more importance. As the buildings became larger, rows of columns were required to support the roof, but in every case the basilican form was retained. The Ark, formerly allowed a mere niche in the wall, was developed into the main architectural feature of the interior, and was flanked with columns, covered with a canopy and richly decorated. The almemar in many cases was joined to the platform in front of the Ark, and elaborate arrangements of steps were provided.

The Ark

The Torah Ark (usually called Aron Hakodesh or Hekhál) is the most important feature of the interior, and is generally dignified by proper decoration and raised upon a suitable platform, reached by at least three steps, but often by more. It is usually crowned by the Ten Commandments and the Torah. The position of the pulpit varies; it may be placed on either side of the Ark, and is occasionally found in the center of the steps.

Other interior arrangements

The modern synagogue, besides containing the minister's study, trustees' rooms, choir-rooms, and organ-loft, devotes much space to school purposes; generally the entire lower floor is used for class-rooms. The interior treatment of the synagogue allows great latitude in design.

For the thirty-three synagogues of India, American architect and professor of architecture Jay A. Waronker has learned that these buildings tend to follow the Sephardic traditions of the tevah (or bimah, the raised platform where the service is led and Torah read) being freestanding and roughly in the middle of the sanctuary and the ark (called the hekhal by Sephardim and the aron ha-kodesh by Ashkenazim) engaged along the wall that is closest to Jerusalem. The hekhals are essentially cabinets or armoires storing the sefer Torahs. Seating, in the form of long wooden benches, is grouped around and facing the tevah. Men sit together on the main level of the sanctuary while women sit in a dedicated zone on the same level in the smaller synagogues or upstairs in a women's gallery.

Interesting architectural and planning exceptions to this common Sephardic formula are the Cochin synagogues in Kerala of far southwestern India. Here, on the gallery level and adjacent to the space provided for women and overlooking the sanctuary below, is a second tevah. This tevah was used for holidays and unique occasions. It is therefore interesting that on more special events, the women are closest to the point where the religious service is being led.

In Baghdadi synagogues of India, the hekhals appear to be standard-sized cabinets from the outside (the side facing the sanctuary), but when opened a very large space is revealed. They are essentially walk-in rooms with a perimeter shelf holding up to one hundred sefer Torahs.

Interior decoration

There are but few emblems that may be used that are characteristically Jewish; the interlacing triangles, the lion of Judah, and flower and fruit forms alone are generally allowable in Orthodox synagogues. The ner tamid hangs in front of the Ark; the tables of the Law surmount it. The seven-branched candlestick, or menorah, may be placed at the sides. Occasionally the shofar, and even the lulav, may be utilized in the design. Hebrew inscriptions are sparingly or seldom used; stained-glass windows, at one time considered the special property of the Church, are now employed, but figured subjects are not used.

Gallery

.jpg) 4th century synagogue in Capernaum, Israel

4th century synagogue in Capernaum, Israel The Central Synagogue of Aleppo. The oldest surviving inscription at the site dates to 834 CE.

The Central Synagogue of Aleppo. The oldest surviving inscription at the site dates to 834 CE. The oldest parts of the Old Synagogue in Erfurt, Germany date to the late 11th century

The oldest parts of the Old Synagogue in Erfurt, Germany date to the late 11th century- The 15th century Old Synagogue in Kraków, Poland

The 17th century Husiatyn Synagogue in Husiatyn, Ukraine

The 17th century Husiatyn Synagogue in Husiatyn, Ukraine The Touro Synagogue (1759) in Newport, Rhode Island is the oldest synagogue in the United States

The Touro Synagogue (1759) in Newport, Rhode Island is the oldest synagogue in the United States The 1869 Rumbach Street Synagogue in Budapest, Hungary

The 1869 Rumbach Street Synagogue in Budapest, Hungary 1869 Great Synagogue in Romantic style in Pécs, Hungary

1869 Great Synagogue in Romantic style in Pécs, Hungary.jpg) 1902 Sarajevo Synagogue in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

1902 Sarajevo Synagogue in Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina- Sinagoga Or Torah (1927) of Buenos Aires, Argentina

.jpg)

Cymbalista Synagogue (1997) by Mario Botta in Tel Aviv, Israel

Cymbalista Synagogue (1997) by Mario Botta in Tel Aviv, Israel

See also

- List of Jewish architects

- Oldest synagogues in the world

References

- Murray Zimiles, Stacy C. Hollander, Vivian B. Mann, and Gerard C. Wertkin, Gilded Lions and Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue to the Carousel, University Press of New England, 2007, p. 5

- Maria and Kazimierz Piechotka, Heaven's Gate: Wooden Synagogues in the Territory of the Former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Institute of Art, Polish Academy of Sciences, Wydawnnictwo Krupski I S-ka, Warsaw, 2004

- Rachel Wischnitzer, The Architecture of the European Synagogue, JPS, Philadelphia, 1964, pp. 125–147

- Carol Herselle Krinsky, Synagogues of Europe: Architecture, History, Meaning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1985, Dover Publications, 1996, pp. 53–58 and in individual town sections

- Alfred Werner, Wooden Synagogues, Commentary, July 1960

- cited in Mark Godfrey, Abstraction and the Holocaust, Yale University Press, 2007, p. 92

- Ori Z. Soltes, Our Sacred Signs: How Jewish, Christian, and Muslim Art Draw from the Same Source, Westview Press, 2005, p. 180

- Maria und Kazimierz Piechotka: Landscape With Menorah: Jews in the towns and cities of the former Rzeczpospolita of Poland and Lithuania. Salix alba Press, Warsaw 2015. Page 73. ISBN 978-83-930937-7-9

- https://publikationsserver.tu-braunschweig.de/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/dbbs_derivate_00009149/Doktorarbeit.pdf Bimah-support. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- Maria und Kazimierz Piechotka: Landscape With Menorah: Jews in the towns and cities of the former Rzeczpospolita of Poland and Lithuania. Salix alba Press, Warsaw 2015. Page 75. ISBN 978-83-930937-7-9

- Rachel Wischnitzer, Architecture of the European Synagogue, Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1964

- Carole Krinsky, Synagogues of Europe; Architecture, History, Meaning, MIT Press, 1985; new edition 1996

- Diana Muir Appelbaum, "Jewish Identity and Egyptian Revival Architecture", Journal of Jewish Identities, July 2012.

- Kalmar, I. D. (2001). "Moorish style: Orientalism, the Jews, and synagogue architecture". Jewish Social Studies, 7(3), 68–100. 69.

- Davidson, Moorish Style. p. 70

- Davidson, Moorish Style. p. 84

- Henry and Daniel Stoltzman, Synagogue Architecture in America; Path, Spirit, and Identity, Images Publishing, 2004, p. 193

- "Synagogues". Jewish heritage Walking tours in Budapest.

- "Jewish Synagogue at Carmel College" Historic England List Entry, retrieved November 4, 2018

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Buildings of England - Oxfordshire - Pevsner Architectural Guides. Penguin. p. 712.

Further reading

- Goldman, Bernard, The Sacred Portal: a primary symbol in ancient Judaic art, Detroit : Wayne State University Press, 1966

- Brian de Breffny, The Synagogue, Macmillan, 1st American ed., 1978, ISBN 0-02-530310-4.

- Carol Herselle Krinsky, Synagogues of Europe; Architecture, History, Meaning, MIT Press, 1985; revised edition, MIT Press, 1986; Dover reprint, 1996

- Rachel Wischnitzer, Synagogue Architecture in the United States, Jewish Publication Society of America, 1955

- Rachel Wischnitzer, Architecture of the European Synagogue, Jewish Publication Society, 1964

- Stolzman, Henry & Daniel, Ed. Tami Hausman (2004). Synagogue Architecture in America: Faith, Spirit, and Identity. Images Publishing. ISBN 1864700742

External links

- Synagogue Architecture, Jewish Encyclopedia

- Early Synagogue Architecture, My Jewish Learning

- American Synagogue Architecture

- Slideshow of Contemporary American Synagogue Sanctuary Architectural Elements