Symphony No. 6 (Haydn)

The Symphony No. 6 in D major (Hoboken 1/6) is an early symphony written in 1761 by Joseph Haydn and the first written after Haydn had joined the Esterházy court. It is the first of three that are characterised by unusual virtuoso writing across the orchestral ensemble. It is popularly known as Le matin (Morning).

Background and scoring

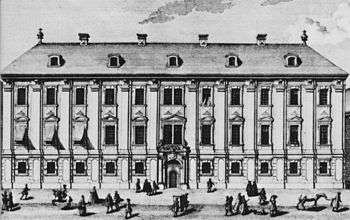

Haydn wrote this, his first symphonic work for his new employer Prince Paul II Anton Esterházy, in the spring of 1761, shortly after joining the court. He had signed his employment contract with him on May 1, 1761. Prince Paul gave Haydn the three times of day as a theme for composition.[1]

The Esterházys maintained in permanent residence an excellent chamber orchestra and with his first contribution for it in the symphonic genre, Haydn fully exploited the talents of the players. In this, Haydn was consciously drawing on the familiar tradition of the concerto grosso, exemplified by the works of Antonio Vivaldi, Giuseppe Tartini, and Tomaso Albinoni then much in vogue at courts across Europe. All three symphonies (Nos. 6, 7 and 8) feature extensive solo passages for the wind, horn and strings, including rare solo writing for the double bass and bassoon in the third movement of No. 6. The work is scored for flute, 2 oboes, bassoon, 2 horns in D, violin I, violin II, viola, cello, double bass, and harpsichord ad libitum.[2][3]

It has been commonly suggested that Haydn's motivation was to curry favour both with his new employer (by making reference to a familiar and popular tradition) and, perhaps more importantly, with the players upon whose goodwill he depended.[4] Typically during this period, players who performed challenging solo passages or displayed unusual virtuosity received financial reward. By highlighting virtually all of the players in this regard, Haydn was, literally, spreading the wealth.

Nickname (Le matin)

The nickname (not Haydn's own, but quickly adopted) derives from the opening slow introduction of the opening movement, which clearly depicts sunrise. The remainder of the work is abstract, as, indeed, are the other two symphonies in the series. Because of the initial association, however, the remaining were quickly and complementarily named "noon" and "evening".[5]

Movements

- Adagio, 4

4 – Allegro, 3

4 - Adagio, 4

4 – Andante, 3

4 – Adagio in G major, 4

4 - Menuet e Trio (Trio in D minor), 3

4 - Finale: Allegro, 2

4

Following the sunrise-depicting introduction, the Allegro kicks off immediately with solo passages for flute and oboe. At the end of the development, a solo horn states the opening flute theme in the tonic, reminding modern listeners of the premature entry of the horn at the end of the development of Ludwig van Beethoven's Eroica Symphony composed forty years later.[6]

The slow movement is an Andante featuring passages for solo violin and solo cello bracketed by an Adagio on both ends. The leading Adagio is based on a hexachord.[6]

The minuet also contains concertante passages. A solo flute is heard accompanied by violins as well as a section with wind-band scoring. The trio begins with solo passages by the double bass and bassoon and are later joined by solo viola. The finale has a concerto grosso feel with virtuosi passages for cello, violin and flute.[6]

See also

- List of symphonies by name

Notes

- Stapert, Calvin (2014). Playing before the LORD. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. pp. 39, 44. ISBN 9780802868527.

- See H. C. Robbins Landon's edition of the score for Symphony No.6 at the German web site Haydn100&7. To display the score for each movement click the link "Partitur lesen" ["Read score"]. The instrumentation for the symphony is shown on page two of the section for the first movement. Accessed 29 May 2009.

- The harpsichord is marked ad libitum, since there is disagreement whether it should be used. Although Landon insists that it is required, James Webster (for Christopher Hogwood) argues that it should not be used, since Haydn was the only keyboard player in the Esterházy orchestra, and he conducted from the violin. Furthermore, there are no figured bass or keyboard parts in any of the authentic Haydn symphony scores (summarized by Threasher, p. 51).

- For a typical commentary, see D. McCaldin, "Haydn Well Served", The Musical Times, Vol. 132, No. 1783 (September 1991), p. 448.

- For information on this symphony generally and for further details, consult H. C. Robbins Landon, The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn (London: Universal Edition. and Rockliff, 1955)

- Brown, A. Peter, The Symphonic Repertoire (Volume 2). Indiana University Press (ISBN 025333487X), pp. 71–72 (2002).

References

- Threasher, David. "Four Seasons in One Day". Gramophone (June 2009), pp. 48–53.