Sydney School of Arts building

The Sydney School of Arts building, now the Arthouse Hotel, is a heritage-listed meeting place, restaurant and bar, and former mechanics' institute, located at 275-277a Pitt Street in the Sydney central business district in the City of Sydney local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by John Verge and built from 1830 to 1861. It is also known as Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1]

| Sydney School of Arts building | |

|---|---|

Sydney_School_of_Arts_Pitt_Street.jpg) The façade of the former School of Arts building, pictured in 2014 | |

| Location | 275-277a Pitt Street, Sydney central business district, City of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33.8723°S 151.2079°E |

| Built | 1830–1861 |

| Architect | John Verge |

| Website | www |

| Official name: Sydney School of Arts; Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts; Arthouse Hotel | |

| Type | State heritage (built) |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 366 |

| Type | School of arts |

| Category | Community facilities |

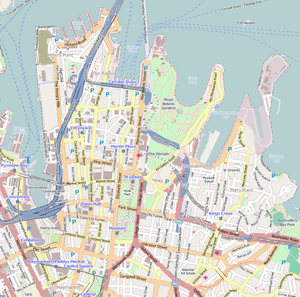

Location of Sydney School of Arts building in Sydney | |

History

The Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts traces its origins to Scotland. In 1800, at the Anderson Institute in Glasgow, George Birkbeck had been appointed Professor of Natural Philosophy. He started giving free talks to working men (then called mechanics). Over the course of the next 20 years these became increasingly popular so in 1821 he opened the first Mechanics' Institute in Glasgow. In the same year a School of Arts was opened in Edinburgh. The aims of both were identical - the diffusion of scientific and other useful knowledge to the working classes.[1]

In 1830 in Colonial New South Wales, John Dunmore Lang, a Presbyterian minister, had ambitions to build an Australian College in Sydney. For this he needed craftsmen so he dispatched his colleague, Henry Carmichael (also a Presbyterian minister in the colony) to Scotland to recruit men to build this college. In 1831 The Stirling Castle sailed from Glasgow to Sydney and on the voyage out Carmichael gave classes to these "mechanics" with the aim of them forming the nucleus of a Mechanics' Institute in Sydney. They arrived on 13 October 1831 and 18 months later the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts was founded on 22 March 1833. The aims and objectives of this institution were the intellectual improvement of its members and the cultivation of literature, science and art. In the years that followed classes and courses in the entire range of liberal arts and sciences were held for both men and women and the SMSA flourished for many years.[2][1]

Early lectures covered chemistry, history and astronomy, but also more quotidian topics such as the principles of taste, the choice of a horse and vulgarities in conversation. Classes, quickly thrown open to women, covered everything from elocution to "simple surgery in 20 lessons". The Rev Samuel Marsden was a member, future Prime Minister Sir Edmund Barton a debater, explorer Ludwig Leichhardt a lecturer. For almost a century the school - temperate, Protestant and Masonic in tone - flourished.[3][1]

The mid 1820s saw the rise of a movement for education in colonial New South Wales. And as was traditionally the case, much educational activity was undertaken by the churches, amidst sectarian disputes. Learned and philanthropic individuals - whether catholic or Protestant - were to participate rigorously in these developments. But as it generally occurred, a large portion of the funds for educational schemes came from public finances.[1]

Establishment

The inauguration of the Sydney Mechanics School of Arts (SMSA) took place over March and April 1833. In the same years, the charter of the Clergy and Schools Corporation - an instrument which bestowed privileged treatment upon the Church of England's Schools via the granting of land, was repealed by the British government. This left the provision of schools in New South Wales as unsystematic as it had been in pre-Corporation days and just as dependent on government funding.[4][1]

After an audience with Governor Sir Richard Bourke, Henry Carmichael - Master of Classics at the Australian College - convened a meeting at the College to discuss the establishment of an "association for the diffusion of scientific and other useful knowledge among the mechanics" of the colony.[5][1]

Difficulties in finding suitable and permanent accommodation were experienced for a time until January 1836, when negotiations to acquire the lease on an allotment in Pitt Street, adjoining the Independent Chapel, were commenced. Plans for a building had been accepted earlier that month, and on 6 February 1838, the new building was used for the first time. The building comprise a theatre, a lecture room, a museum and a library. The theatre, situated on the ground floor, had a curved front and was accessible via the centrally placed Colonial Georgian doorway with pediment which provided entry to the building. The library and reading room - both on the first floor - had a public entrance up stairs at the left rear of the building.[1]

Early in 1845, the Committee purchased the leasehold of their Pitt Street allotment and plans to add two rooms for the Librarian were commenced. Supervised by J. S. Duer and undertaken by a Mr Mackeller, these private apartments were completed early in the following year.[1]

Having received permission by a special Act of Parliament in 1853 to dispose of a piece of land reserved for the SMSA in the Haymarket, the Trustees commenced searching for a new site. Finally on 7 January 1855, the Independent Chapel was advertised for sale. The Chapel was quickly purchased and incorporated into the SMSA.[1]

During the period 1845 to 1855, the original SMSA had required constant renovation and repair. On 3 May 1855, Bibb reported to the Committee that pending work suggested reconstruction of the two buildings rather than further renovations. (The Chapel had been found to be built without solid foundations on low, damp ground). Costs of rebuilding and the need to amend the Sydney Mechanics School of Arts Act, 1852, caused delays. In the interim the old theatre was converted to a reading room while an opening was created to allow access to the Chapel which was then used as a new lecture theatre.[1]

The first set of plans for reconstruction were drawn up by John Bibb though only the façade design was brought to fruition. The foundation stone was laid by Governor Sir William Denison, the school's patron, at a ceremony on 19 December 1859. Work on the façade was completed late in April 1860.[1] The second set of plans were also designed by Bibb, though this time work was divided into two stages in order to allow the School to continue functioning. The first stage included all stonework and most of the alterations, narrow corridors giving access to various rooms, a library and reading room located on the ground floor, reductions in the size of the classrooms and the librarian's accommodation, and three single sets of stairs. Work commenced in September 1860 and was finalised in 1861. The second stage entailed rebuilding the Independent Chapel which was to continue as the lecture hall. Rebuilding began in December, 1861, and was completed on 6 September 1862. Work was delayed as a result of Bibb's death in February 1862. Special attention was paid to the Chapel's ventilation.[1]

The SMSA had commenced its institutional life for literary and recreational proposes and as a place where science and technical drawing, the keys and blueprints to nature, could be imparted to ordinary men. The desire for theoretical knowledge was to grow during the 19th century. As industrialisation took root, setting off the education revolution of the 1870s and 1880s, knowledge and its acquisition became central to the generation of wealth. Now, more than ever, Mechanics' Institutes could assist in colonial development and in the 'process of upward social mobility among workmen ambitious to "improve themselves in all ways".[6][1]

Thus in February 1873, the establishment of a Technical or Working Men's College was discussed and in July 1874, arrangements were made to lease a vacant allotment behind the School of Arts in George Street. These arrangements, however were not concluded until May 1877, though the plans for a college building were accepted from Benjamin Backhouse, having won the Committee's competition for a design.[1]

The Technical or Working Men's College was to provide specialised Technical Education - advocated by engineer Norman Selfe and others.[2][1]

With a grant from the Minister for Public Instruction towards the project, a tender from Messrs. Creber and Roberts was accepted on 30 July 1877. Stage 1 of the work was completed in October 1878. Stage 2 was finalised in March of the following year. The lack of funds hampered the growth of the College and its courses until at last, in 1888, the colonial government established a Board of Technical Education. During September, arrangements were made for the transferral of the Working Men's College to the Board.[1]

The State took over the running of the College and in time it became the Sydney Technical College - later to be formed into the University of Technology Sydney.[2][1]

Subsequently, the SMSA reverted to its previous functions and in 1887, architect John Smedley redesigned its accommodation. A Ladies Reading room, a Smoke room and a stage in Bibb's lecture theatre were added. These alterations were finished in September 1888. With the removal of the college, the SMSA's revenue declined. As a result, the Committee moved to incorporate shops into the Pitt Street frontage. The library, the Ladies Reading room and the Secretary's office were relocated and the shops installed. Work was supervised by architect A. McQueen and was completed by June 1896.[1]

Developments during the twentieth century

By the 1930s, its prospects were bleak. Other education centres had been spun off. State funding and Vice-Regal patronage had been withdrawn. Membership, which had peaked at more than 3,000, had plummeted.[3][1] By the 1970s the SMSA was in difficulties. Education was no longer provided by the SMSA as this function had long been assumed by the State and Federal Governments. The Board were left with a large heritage building to maintain, a membership that had long been in decline but who nonetheless supported the large library. Developer Alan Bond offered to purchase the building outright and he signed a mortgage with the Board of Trustees. Then Bondcorp collapsed.[1]

In 1992 a Japanese consortium bought out the mortgage and with the now substantial funds the Board purchased 280 Pitt Street (an 11-storey office block from 1925) from the Uniting Church, refurbished it as a new home for the SMSA (which occupies three floors) and created offices and retail spaces on other floors.[2][1]

Today the School of Arts' building has been restored as the Arthouse Hotel.[3][1]

Description

A two-storey sandstone façade. The ground floor has been drastically altered. The façade is an example of restrained classicism in the Palladian style and is typical of late Georgian sandstone elevations now rare in Sydney.[1]

Condition

As at 26 August 1997, the physical condition of the building was good.[1]

Modifications and dates

- 1830 - Independent Chapel built for Congregationalists by John verge

- 1836 Original Sydney Mechanics School of Arts (SMSA) commenced construction around April

- 1838 - SMSA building first used 6 February

- 1838/39 Two rooms erected at rear SMSA on southern side: completed 7 January 1839

- 1849 Completion of two rooms at rear of building, northern end for Librarians "private apartments" early this year

- 1845-55 Constant renovation and repair: including roof reshingled, interior and exterior wall cleaned, gutters cleaned, skylight repaired, water supplied to building.

- 1855 Independent Chapel advertised for sale 7 January: purchased by Trustees and incorporated into SMSA.

- c. 1855-7 Old theatre in original building converted to a Reading Room and opening created through to the Chapel; Chapel then used as new Lecture Theatre.

- 1858-62 Bibb asked to prepare plans for new building 5 August 1858.

- 1859 Foundation stone laid on 19 December.

- 1860 Façade completed late April, though remainder of plan not carried out.

- 1860 Plans prepared by Bibb for rebuilding in 2 stages.

- 1860-1 Stage 1 - stonework and most alterations except new hall commenced September and finished late January 1861. Included narrow corridors giving access to various rooms; Library and Reading Room located on ground floor; classrooms and Librarian's accommodation reduced; three single sets of stairs.

- 1861-2 Stage 2 - rebuilding lecture hall (former Independent Chapel) commenced December, 1861, and completed 6 September 1862.

- 1878-9 Technical or Working Mens College, designed by Benjamin Backhouse, constructed at rear of SMSA: Stage 1 completed October 1878; Stage 2, alterations to building, completed March 1879.

- 1883 Late 1883, Working Mens College transferred to Board of Technical Education: SMSA reverted to a place of literary and recreational pursuits.

- 1887-8 John Smedley engaged to redesign SMSA accommodation in 1887: alterations also included provision of a Ladies Reading Room, a Smoke Room and the addition of a stage in Bibb's lecture theatre. Alterations completed September, 1888.

- 1896 Shops incorporated into Pitt Street front (architect A. McQueen). Also included relocation of Library, Ladies Reading Room and Secretary's office. Completed June, 1896.[1]

Heritage listing

As at 20 October 2004, the School of Arts building is an important link in the history of Sydney's cultural growth. It has stood on the present site since 1837, and has seen important early cultural and educational activities, including the first courses in drawing for Australian trained architects, and the first performance of a Gilbert and Sullivan musical in Sydney. It is directly linked with the formation of Sydney Technical College.[1]

The facade of the School of Arts is an important survivor of 19th Century Sydney. It shows John Bibb's skills as a later Regency/early Victorian designer, and this transitional aspect is of real interest showing a high degree of creative achievement.[1]

The surviving 19th Century interior reveals fashionable taste and detail, especially plasterwork, stencilling and sklights. The remains of the 1830 chapel interior give further significance to the interior, and reveal acceptance of building re-use and adaption.[1]

The School of Arts was an important educative and social centre for Sydney's intelligensia in the 19th century and its character and spaces still demonstrate aspects of an earlier way of life. The Governor was its patron and leading citizens such as J.H. Goodlet (brick manufacturer) and Norman Selfe (engineer) served on its committee.[1]

Technical education in New South Wales has its chief focus in the School of Arts prior to the transfer of the facility to the government in the later 19th century[7][1]

Sydney School of Arts was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999.[1]

See also

References

- "Sydney School of Arts". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00366. Retrieved 13 October 2018.

- Sydney Mechanics School of Arts, 2007,6

- Huxley, in The Sydney Morning Herald, 15–16 March 2008, p.11

- Burnswoods and Fletcher 1980

- Riley 1982

- Cannon 1978

- Tanner & Associates 1987

Bibliography

- "Sydney School of Arts". 2007.

- Attraction Homepage (2007). "Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts".

- Howard Tanner & Associates (1987). Conservation Plan.

- Huxley, John (2008). "Oasis of reading quenches thirst for knowledge - 175 years young". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts (2007). Annual Report & Audited Accounts of the SMSA for the year 1 January 2007 to 31 December 2007.

Attribution

![]()

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sydney School of Arts building. |