Swa Saw Ke

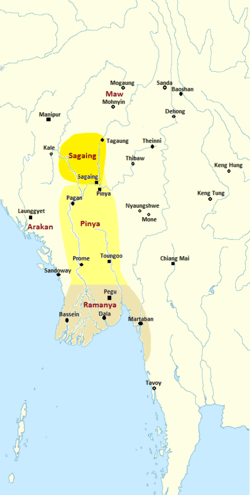

Mingyi Swa Saw Ke (Burmese: မင်းကြီး စွာစော်ကဲ, pronounced [mɪ́ɴdʑí swà sɔ̀ kɛ́]; also spelled စွာစောကဲ, Minkyiswasawke or Swasawke; 1330–1400) was king of Ava from 1367 to 1400. He reestablished central authority in Upper Myanmar (Burma) for the first time since the fall of the Pagan Empire in the 1280s. He essentially founded the Ava Kingdom that would dominate Upper Burma for the next two centuries.

| Swa Saw Ke စွာစော်ကဲ | |

|---|---|

| King of Ava | |

| Reign | 5 September 1367 – April 1400 |

| Coronation | 29 March 1368 or (16 March 1368) |

| Predecessor | Thado Minbya |

| Successor | Tarabya |

| Chief Minister | Min Yaza |

| Governor of Amyint | |

| Reign | 1351 – 5 September 1367 |

| Successor | Tuyin Theinzi |

| Governor of Yamethin | |

| Reign | 1351 |

| Predecessor | Thihapate |

| Successor | Thilawa |

| Governor of Talok | |

| Reign | c. 1344 – 1351 |

| Successor | Yazathu |

| Born | 16 July 1330 Monday, 1st waxing of Wagaung 692 ME Thayet, Pinya Kingdom |

| Died | April 1400 (aged 69) c. Kason 762 ME Ava (Inwa), Ava Kingdom |

| Consort | Khame Mi Shin Saw Gyi Saw Omma Saw Taw Oo |

| Issue among others... | Tarabya Minkhaung I Theiddat Thupaba Dewi |

| House | Pinya |

| Father | Min Shin Saw |

| Mother | Shin Myat Hla |

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism |

When he was elected by the ministers to succeed King Thado Minbya, Swa took over a small kingdom barely three years old, and one that still faced several external and internal threats. In the north, he successfully fought off the Maw raids into Upper Burma, a longstanding problem since the waning days of Sagaing and Pinya kingdoms. He maintained friendly relations with Lan Na in the east, and Arakan in the west, placing his nominees on the Arakense throne between 1373 and 1385. In the south, he brought semi-independent kingdoms of Toungoo (Taungoo) and Prome (Pyay) firmly into Ava's orbit. But his attempts to extend control farther south touched off the Forty Years' War (1385–1424) between Ava and Pegu. After three defeats, Swa had to agree to a truce with King Razadarit of Pegu in 1391.

For the most part, his long reign was peaceful. In contrast to the short reigns by various kings since the fall of Pagan, Swa's 32-year reign brought much needed stability to Upper Burma. He redeveloped the economy of the kingdom by repairing the irrigation system, and reclaiming much of the arable land which had lapsed into wilderness for nearly a century as the result of the Mongol invasions and repeated Maw raids. Under Swa's leadership, Upper Burma centered in Ava, finally achieved stability it had lacked for much of the past hundred years.

Early life

The future king was born Saw Ke (စောကဲ)[note 1] on 16 July 1330[note 2] in Thayet to the ruling family of the region, which was then a vassal state of Pinya.[1] His father Gov. Min Shin Saw of Thayet was a son of King Kyawswa of Pagan, and his mother Shin Myat Hla was a niece of King Thihathu of Pinya and granddaughter of King Narathihapate of Pagan. The third child of six, Ke had two elder brothers Shwe Nan Shin and Saw Yan Naung, and three younger sisters, Saw Pale, Saw Myat and Saw Omma.[1] Then reigning king Uzana I of Pinya was their paternal half-uncle.

Ke spent his formative years in Launggyet, the capital of Arakan, the kingdom to the west of Thayet. In early January 1334, the Arakanese raided Thayet, and sent the entire family of the governor to Launggyet on 7 January 1334.[2] The family was treated well at the Arakanese court where the children were educated by one of the most learned Arakanese monks of the day. Becoming a scholar in his own right, the young prince conducted himself well, and became popular in court circles and also with common people.[3]

Early career

Governorships

In 1343/44,[note 3] the family was allowed to leave Launggyet. They returned to Pinya. At Pinya, the family was well received. His father was reappointed to his old post at Thayet. His two elder brothers became governors of Myinsaing and Prome (Pyay). Ke, still in his early teens, was made governor of a small town called Talok in central Burma, with the title of Tarabya (တရဖျား, "Righteous Lord"). When he grew older, c. 1351, he was made governor of Yamethin, a larger town by King Kyawswa I of Pinya, his first cousin once removed.[note 4]

Defection to Sagaing

In December 1350, King Kyawswa I suddenly died, and was succeeded by his son Kyawswa II. Ke did not get along with Kyawswa II, who was not only his second cousin but also brother-in-law. (Kyawswa II's chief queen was Saw Ke's youngest sister Saw Omma.[4]) Ke defected to Sagaing, whose reigning king Tarabya II was also a second cousin of his. His defection was a second major defection to Sagaing in two years, following an even higher profile defection of Gov. Nawrahta of Pinle in 1349.[5] But the king of Sagaing sent an embassy led by Princess Soe Min and Gov. Thado Hsinhtein of Tagaung to cool the tensions. The embassy was successful, and the peace between the two Burmese-speaking kingdoms was maintained.[6] Tarabya II appointed Ke governor of Amyint, a small region west of Sagaing.[1][7]

Early Ava

Saw Ke's rise to power began in the mid-1360s. In September 1364, Prince Thado Minbya of Sagaing seized both Sagaing and Pinya capitals, which had been left in ruins by a devastating Maw Shan raid earlier that year, and declared himself king of both Sagaing and Pinya kingdoms.[8] Ke pledged allegiance to the 18-year-old king, who was not only his second cousin once removed but also brother-in-law. The young king had married Ke's sister Saw Omma.[8] On 26 February 1365, Thado Minbya founded the Kingdom of Ava as the successor state of both Sagaing and Pinya.[9]

Despite his proclamation, the young king still had no control over Pinya's southern vassals. Over the next two years, the young king launched repeated campaigns to gain control of the southern regions. By his sudden death in September 1367 from smallpox, the young king had only partially completed the conquests. The southernmost regions Prome, Toungoo (Taungoo) and Sagu (Minbu granary) all remained out of Ava's grasp.

Accession and coronation

Saw Ke became king due to the recommendation of his brother-in-law Gov. Thilawa of Yamethin. After Thado Minbya's death, Queen Saw Omma and Commander Nga Nu tried to seize the Ava throne but the court drove them out.[10] The court initially gave the throne to Thilawa. But the taciturn governor of Yamethin refused, reportedly saying: "I do not open my mouth to speak three or four words a day. You had better choose Saw Ke."[11][3] The court offered the throne to Ke, who accepted. He became king of Ava on 5 September 1367.[12]

His first job as king was to retake Sagaing where his sister and her lover had been trying to revive the old Sagaing Kingdom. His forces easily retook Sagaing. Over the next few months, he was able to use diplomacy to persuade the southern vassals, whom Thado Minbya could not conquer militarily, to acknowledge him as king. That Gov. Saw Yan Naung of Prome and Gov. Theinkhathu Saw Hnaung of Sagu were his elder brother and brother-in-law, respectively, may have helped. To be sure, his authority was nominal: Pyanchi I of Toungoo offered nominal allegiance to Ava only because he himself was consolidating his power at Toungoo, and would later attempt to revolt.[13]

On 16 March 1368 or on 29 March 1368, the date deemed propitious by his court astrologers, Saw Ke, 37, was crowned king.[note 5] Now known as Mingyi Swa, ("Exalted Great King"),[12] he made his first wife Khame Mi the chief queen, and raised Thado Minbya's three younger sisters as his principal queens.[14]

Reign

Swa shared Thado Minbya's dream of restoring the erstwhile Pagan Empire.[15] He would spend the next two decades gradually reestablishing central authority throughout the Irrawaddy valley and its periphery. The king came to rely on the advice of his court, led by Chief Minister Min Yaza, a commoner who joined his service in 1368. Despite the ambition, at his accession his real authority did not exceed outside the immediate core region of Central Burma. He decided to bide his time, and deal with his internal and external issues one at a time. At the top of his list was the Shan state of Maw (Mong Mao), which had been assiduously raiding Upper Burma since 1356.[15][16]

Establishing borders

Ramanya

In order to deal with the Maw threat, Swa initially pursued a conciliatory policy towards his other neighbors.[3] To be sure, the neighboring states themselves looked at the newly rising power from Central Myanmar, the traditional home of political power in Myanmar, with caution. In 1370, King Binnya U of the southern kingdom of Ramanya proposed friendly relations. The king of the Mon-speaking kingdom wanted a quiet northern border as he had been facing a serious rebellion in Martaban (Mottama) and the Irrawaddy delta since 1363/64.[17] Swa too wanted a quiet border, and in particular Binnya U's assurance that Ramanya would not assist Toungoo. The two kings met later in the year 1370/71 at the frontier, and signed a treaty demarcating the border.[18][19]

Maw

With his rear secure, Swa turned his attention to the north. The situation turned to his favor when the longtime sawbwa Tho Kho Bwa (Si Kefa) died in 1371. Swa took full advantage of the ensuing chaos and infighting between Mohnyin and Kalay states. Following the court's advice, he marched to both Kalay and Mohnyin only after the two states were exhausted from their war. Both states submitted to the rising power.[20][21] But the Ava-installed sawbwa of Mohnyin was overthrown soon after the Ava forces left. Swa wanted to retaliate but was stopped by the court, which advised that he was not yet strong enough to engage in an extended war. Heeding the court's advice, Swa agreed to re-calibrate his northern border farther south to Myedu, where the court considered defensible. To be sure, the new sawbwa at Mohnyin did not agree with Ava's new border. The Maw forces occupied Myedu in 1372 but Swa drove them out by early 1373.[22][note 6] An Ava inscription dated 7 February 1375 triumphantly commemorates the victory over the "heretic Shans".[23]

An uneasy ceasefire of sorts followed for the next 14 years. The Maw state still wanted to regain Kalay and Myedu but stopped its raids into the lowlands now that it faced a more united lowland kingdom in Ava. The next Maw attacks would come in 1387–88 and 1392–93 while Ava was immersed in its ultimately unsuccessful effort to take over Pegu.

Arakan

His success in containing the Maw threat gave Swa additional leeway to deal with other issues. In 1373, Swa sided with an Arakanese (Rakhine) faction over the recently vacated Arakense throne at Launggyet.[note 7] Swa's nominee, his uncle Saw Mon II proved an able ruler and ruled Arakan until his death in 1380/81 (or 1383/84).[note 8] This time, Swa sent Saw Me, governor of Talok and one of his long-serving loyalists, to Arakan.[note 9] But Saw Me proved to be a tyrant and was driven out of Arakan in 1385/86.[24][25] Swa chose not respond as his attention was now focused on Pegu. Ava would return to Arakan and finish off the Launggyet dynasty in 1406.

Toungoo

Despite his relative successes in his near abroad, Swa still had little control over his own vassal Toungoo. He never trusted Gov. Pyanchi of Toungoo, who was educated in Pegu and had been contact with Pegu during Ava's brief war with Maw. As a first step, in 1374, Swa asked Toungoo's eastern neighbor Lan Na not to interfere. Chronicles say after he had threatened to send a sizable force to the frontier, Chiang Mai sent an embassy to Ava, and agreed to a peace treaty.[26] But Chiang Mai might have simply let Ava and Pegu fight it out. At any rate, Pyanchi now recognized that Ava was trying to isolate him, and asked Pegu for military aid. Despite the 1370 non-aggression pact, Binnya U sent a sizable force consisting of infantry, cavalry and war elephants to Toungoo.[27]

Ava was not yet willing to go to war with Pegu over Toungoo. Instead, the king sought another way, and enlisted the help of his brother Gov. Saw Yan Naung of Prome. In 1375, Yan Naung proposed a marriage of state between his daughter and Pyanchi's son, Pyanchi II, with the marriage ceremony to be held in Prome (Pyay).[27] Pyanchi understood the proposal of marriage to be the first step toward joint rebellion against Ava. A Toungoo−Prome axis backed by Pegu would form a formidable Lower Burma bulwark against Central Burma-based Ava. Pyanchi I agreed to the proposal, and went to Prome with a small battalion. It was a trap. The Toungoo contingent was ambushed near Prome, and Pyanchi was killed although his son and son-in-law Sokkate both escaped.[28][29]

Even then, Ava still had little control. The Peguan army led by Commander Ma Sein remained in control of Toungoo before the city was retaken three months later.[30][31] By then, Ava had sent three expeditions against Toungoo, causing widespread starvation in Toungoo.[32] Swa allowed Pyanchi I's son Pyanchi II to take office in early 1376. But Pyanchi II was assassinated three years later by his brother-in-law Sokkate. Swa initially accepted Sokkate's allegiance in 1379/80 but changed his mind after Sokkate proved to be a tyrant. He had Sokkate assassinated by a spy of his, and appointed the assassin, Phaungga, in 1383. In Phaungga, Swa believed he finally had a trustworthy vassal at Toungoo.[30][33]

At half-way point

By 1384, at the half way point of his 32-year reign, Swa had successfully consolidated his rule over Upper Burma. He faced no immediate internal or external threats. Lan Na and Arakan, were never a threat to Ava. In the south, King Binnya U of Pegu had died and his teenage son Razadarit was facing two major rebellions. Swa's main concern remained in the north, despite the uneasy truce that had held since 1373. He followed the developments in Yunnan where the Chinese Ming dynasty had been reestablishing Beijing's authority since 1380, and pressuring Shan migrations towards the Irrawaddy valley. According to Ming records, Swa asked China for a joint operation against the border Shan states but Burmese chronicles make no mention of such a request.[note 10]

At any rate, he had helped restore a semblance of normalcy throughout the country. It was especially true in war-torn northern Burma (former Sagaing Kingdom) which had seen repeated Mongol and later Shan invasions since the late 13th century. Indeed, several paddy fields that had been since the Mongol invasions were restarted only in 1386.[32] By all accounts, he had successfully established some degree of central control over his vassals, including Toungoo, by the eve of the war with Pegu. One notable natural disaster during the first half of his reign was a major earthquake that struck on 30 December 1372.[note 11]

War with Pegu

Circa April 1385, he appointed his eldest son Min Na-Kye (Tarabya) heir-apparent. In a marriage of state, he married his son to his niece, daughter of Thilawa of Yamethin.[34] Meanwhile, the king received an embassy from Gov. Laukpya of Myaungmya, seeking military assistance in exchange for his submission to Ava. Swa's acceptance of Laukpya's invitation resulted in the Forty Years' War between Ava and Pegu.

Initial invasions

At first, the Ava court, though still concerned about the situation in the north, believed that Lower Burma was winnable. The teenage king at Pegu barely controlled one out of the three Mon-speaking regions of Lower Burma. The southern Martaban province and the entire Irrawaddy delta had been essentially independent since 1363/64, and formally independent since Binnya U's death in 1384. All Ava needed to do, it seemed, was to take the Pegu province (present-day Yangon Region and southern Bago Region). The court advised Swa to accept Laukpya's offer.

In December 1385,[note 12] Swa launched a two-pronged invasion of Lower Burma down the Irrawaddy and Sittaung rivers, and Laukpya sent in his navy from the delta. The two Ava armies (combined 13,000 men, 1000 cavalry, 40 elephants) were officially led by Swa's young sons, Crown Prince Tarabya, 17, and Prince Minkhaung of Pyinsi, 12; the youngsters were aided by Swa's two best generals, Thilawa and Theinkhathu. The invading armies, assisted by Laukpya's forces, went on to occupy much of the Pegu province but could not break through the Hmawbi–Pegu corridor for over five months. Then, Razadarit made a tactical error. The young king came out of Pegu, and counterattacked the Ava-occupied Fort Pankyaw. Ava forces nearly cornered Razadarit outside Pegu but Razadarit made it inside the capital due to Minkhaung's failure to follow orders.[35][36]

It turned out to be the best shot Ava had at toppling Razadarit. The Ava armies would not come as close to defeating Razadarit until 1414–15. Swa decided to lead the next invasion in the following dry season himself. What was the largest mobilization yet, nearly 30,000 troops invaded by the Irrawaddy, and by land in late 1386. Swa led the riverborne invasion force (17,000 troops on 1000 small war boats, and 1200 cargo boats) while Tarabya led the army (12,000 troops, 600 cavalry, 40 elephants). Minkhaung stayed behind to guard the capital. This time, Peguan defenses were ready. Although they were outnumbered, Razadarit's over 11,000 troops staved off several Ava attacks at Dagon, Hlaing, Dala (modern Twante) and Hmawbi. The invaders once again had to retreat at the onset of the rainy season.[37][38]

Hiatus

Swa was stunned by the failures, and paused the war effort to reassess. At any rate, he needed to deal with his northern border, as it was again restive. Perhaps encouraged by Ava's failures in the south, Maw was breaching Kalay's border. Ava had to send an army in 1387−88 to restore order.[39] The situation remained tense until 1389/90 when Ava and Maw agreed to a truce. King Tho Ngan Bwa of Maw sent his daughter Shin Mi-Nauk to Ava in a marriage of state to Swa's second eldest son Minkhaung.[40]

Meanwhile, Razadarit took full advantage of Ava's preoccupation in the north. In 1387–88, Razadarit managed to capture the Martaban province after a long invasion.[41] By 1389, Razadarit felt ready to take on Ava's ally Laukpya, and invaded the Irrawaddy delta. As in Martaban, Razadarit was close to defeat when he pulled out a victory. The Pegu forces went on to occupy the entire delta, including Ava's territory, Gu-Htut (modern Myan-Aung).[42][43][44]

Resumption and truce

Razadarit's occupation of Gu-Htut forced Swa's hand. In 1390,[note 13] he launched another two-pronged invasion, again by the Irrawaddy and land. Just as in the second invasion, Swa himself led the 17,000-strong river-borne invasion forces and Tarabya led the 12,000-strong army by the Toungoo route.[45] But unlike with the second invasion, the invaders faced unified more numerous southern forces. They could not even breach the border forts. The smaller Peguan navy held off repeated charges by the Ava navy near Gu-Htut. Likewise, Tarabya's army could not take Fort Pankyaw. Despite the success, the Pegu command decided to cede Gu-Htut in exchange for peace. It was a face-saving measure, and Swa accepted the deal.[46]

The truce almost broke down the following dry season. Ava sent an army to Tharrawaddy (Thayawadi) in 1391–92 but Pegu sent a sizable force to the front. The fragile peace held.[47]

Resumption of war with Maw

In the meantime, the fragile peace with Maw had broken down. The cause was again Myedu, the territory Ava wrested away from Maw two decades earlier. Maw forces occupied Myedu in 1392. In the dry season of 1392–93, Swa responded with a combined land and naval attack. But the army led by Theinkhathu Saw Hnaung and Tuyin was badly defeated, and chased all the way back to Sagaing. But Maw forces had overextended, suddenly found themselves deep in central Burma. The Ava counterattack led by Thilawa wiped out all 15 regiments of the Maw army, at Shangon, 30 km northwest of Sagaing.[48][49] After the crushing defeat, the Maw raids ended for the rest of Swa's reign.[28]

Final years

The rest of his reign saw no more wars. He had successfully built a stable state in Upper Burma. After an impactful reign of 32 years, the king died in April 1400.[note 14] He was succeeded by Tarabya.[12] His formal royal titles were: Assapati Narapati Bhawa Natitya Pawara Dhamma-Raja and Siri Tiri Pawanaditya Pawara Pandita Dhamma-Raja.[12]

Administration

Swa heavily relied on the advice of his court led by Chief Minister Min Yaza. He continued to employ Pagan's administrative model of solar polities[50] in which the high king ruled the core while semi-independent tributaries, autonomous viceroys, and governors actually controlled day-to-day administration and manpower.[51][52]

| Vassal state | Region | Ruler (duration in office) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pagan (Bagan) | Core | Uzana II of Pagan (1325−68) Sithu (1368–90?) Uzana III (1390?–1400) |

Uzana III, also known as Thinkhaya, may have been governor earlier than 1390.[note 15] |

| Myinsaing | Core | Shwe Nan Shin (c. 1344–90?) Thray Sithu (by 1390–1426) |

Swa's eldest brother grandson of King Uzana I of Pinya |

| Mekkhaya | Core | Saw Hnaung (1367–?) | |

| Pinle | Core | Min Letwe (c. 1349−86)[note 16] Thray Thinkhaya (1386–?)[45] |

Min Letwe, son of Kyawswa I of Pinya, KIA (1386) |

| Pinya | Core | Thray Waduna (1380s)[45] | |

| Paukmyaing | Core | Min Pale (c. 1347−1402) | |

| Lanbu | Core | Yandathu I (1340s)[53] | |

| Wadi | Core | Thinkhaya (c. 1344–?)[53] | |

| Sagaing | North | Yazathingyan (c. 1367−1400) | |

| Dabayin | North | Theinkhathu (?)[13] | |

| Tagaung | North | Thihapate (1367–1400) | also known as Nga Nauk Hsan; assassin of Tarabya (1400) |

| Kalay | North | Tho Chi Bwa (1371–?)[18] | |

| Myedu | North | Thet-Shay Kyawhtin (c. 1373–?)[13] | |

| Yamethin | Mid | Thilawa (c. 1351−95/96) Maha Pyauk (1395/96−1400) |

Swa's brother-in-law Pretender to Ava throne (1400) |

| Taungdwin | Mid | Thihapate (by 1366–?)[54] | |

| Nyaungyan | Mid | Baya Kyawthu (1360s)[13] | |

| Sagu | Mid | Theinkhathu (c. 1360s–90s) | Swa's brother-in-law |

| Prome (Pyay) | South | Saw Yan Naung (1344–77/78) Myet-Hna Shay (1377/78–1388/89) Htihlaing (1388/89–90) Letya Pyanchi (1390–1413) |

Swa's younger elder brother Swa's nephew Son-in-law of Laukpya of Myaungmya |

| Toungoo (Taungoo) | South | Pyanchi I (1367–75) Pyanchi II (1376–79/80) Sokkate (1379/80−1383) Phaungga (1383–97) Saw Oo I (1397–99) Min Nemi (1399–1408) |

Legacy

Swa left a unified Upper Burma although he could not restore the Pagan Empire. His 32-year reign brought much needed stability to Upper Burma. The stability in turn allowed the populace to repair the irrigation system, and reclaim much of the arable land which had lapsed into wilderness as the result of the Mongol invasions nearly a century earlier.[3][32] This redevelopment recharged Upper Burma's economic and manpower that would allow Ava to pursue more expansionist policies by its later kings.

Family

The king had several queens and at least 13 issue. Most chronicles say that his successor Tarabya was born to his chief queen consort Khame Mi. But the chronicle Yazawin Thit cites a 1401 inscription by Queen Shin Saw Gyi herself which says she was the mother of Tarabya.[note 17]

| Queen | Rank | Issue |

|---|---|---|

| Khame Mi | Chief queen (r. 1367−c. 1390s) | Min Padamya Saw Salaka Dewi Minkhaung Medaw Yan Aung Min Ye |

| Shin Saw Gyi | Queen of the Northern Palace (r. 1367−c. 1390s) Chief queen (r. c. 1390s–1400) |

Tarabya, King of Ava (r. 1400) Saw Myat Ke Saw Swe |

| Saw Omma | Queen of the Middle Palace (r. 1367−c. 1390s) Queen of the Northern Palace (r. c. 1390s–1400) |

Saw Chantha Kyawswa |

| Saw Taw Oo | Queen of the Western Palace (r. 1367−c. 1390s) Queen of the Central Palace (r. c. 1390s–1400) |

Soe Min Wimala Dewi |

| Saw Nanda[12] | Junior queen | ? |

| Shin Shwe[12] | Junior queen (m. 1351/52) | ? |

| Saw Beza | Junior queen (m. 1373) | Minkhaung I, King of Ava (r. 1400–22) Theiddat Thupaba Dewi |

Historiography

| Source | Birth–Death | Age | Reign | Length of reign | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zatadawbon Yazawin (List of Kings of Ava Section) | c. July 1331 – 1401 | 69 (70th year) |

1367/68 – 1401 | 33 | [55] |

| Zatadawbon Yazawin (Horoscopes Section) | 5 July 1331 – 1400 | 68 (69th year) |

1366/67 – 1400 | 33 | [note 18] |

| Maha Yazawin | c. 1331 – November/December 1400 | 69 (70th year) |

29 March 1368 – November/December 1400 | 33 [sic] | [56] |

| Mani Yadanabon | c. 1330/31 – mid 1400 | 16 March 1368 – mid 1400 | [57] | ||

| Yazawin Thit | c. 1330/31 – mid 1400 | 29 March 1368 – mid 1400 | [58] | ||

| Hmannan Yazawin | c. 1331 – November/December 1400 | 29 March 1368 – November/December 1400 | [59] | ||

| Inscriptions | ? – [early-to-mid 1400] | ? | 5 September 1367 – [early-to-mid 1400] | 32 | [12] |

Ancestry

| Ancestry of Mingyi Swa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- The prevailing spelling စော်ကဲ is based on the pronunciation when spoken together with Swa. Among the major chronicles, only Yazawin Thit uses the formal spelling instead of the more common pronunciation-based one.

- The chronicle Zatadawbon Yazawin (Zata 1960: 46, 72) says he was born on Monday, the 1st nekkhat of the 5th month of 693 ME (1st waxing of Wagaung 693 ME), which translates to Friday, 5 July 1331. But 693 ME is most probably a typographical error. It should be 692 ME for a couple of reasons. First, he died c. April 1400 based on a contemporary inscription (Than Tun 1959: 128), which says Swa and his successor Tarabya were already dead by 25 November 1400, as well as the main chronicles (Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 304) and (Hmannan Vol. 1 435−436) which say that he died in 1400 in his 70th year (age 69) and his successor Tarabya ruled for seven months. It means Swa Saw Ke was most likely born in 692 ME (29 March 1330 to 28 March 1331). Secondly, 1st waxing of Wagaung 692 ME gives the correct weekday of Monday, 16 July 1330.

- The Arakanese chronicle Rakhine Razawin Thit (Sandamala Linkara Vol. 1 1999: 181) says the family left Launggyet for Pinya in 705 ME (28 March 1343 to 27 March 1344) but the Burmese Hmannan chronicle (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 403) says the family returned near the end of King Uzana I c. 704 ME (28 March 1342 to 27 March 1343). According to inscriptional evidence (Than Tun 1959: 124), Uzana I's reign ended on 1 September 1340.

- Chronicles (Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 280) and (Hmannan Vol. 2003: 403) say Swa defected to Sagaing during the reign of Tarabya II of Sagaing (r. 1349–52). According to a contemporary inscription (Than Tun 1959: 128), he was still governor of Talok at age 21 (22nd year). Therefore he likely became governor of Yamethin sometime between 24 July 1351 (Swa's 21st birthday) and 23 February 1352 (Tarabya II's death).

- Hmannan (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 402) says he was crowned king on the new year's day of 730 ME (29 March 1368). But Mani Yadanabon (Mani Yadanabon 2009: 35) says he became king on Thursday, 12th waning of Tabaung 729 ME (Thursday, 16 March 1368).

- His forces were probably in Myedu c. January 1373, if not earlier. His son Minkhaung I, by Saw Beza, whom Swa first met on campaign near Myedu per (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 410), was born on 13 September 1373 per (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 264, footnote 3).

- (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 190, footnote 4): No Arakanese chronicles say that the Launggyet court asked for a nominee. Instead, the period was ruled by King Min Hti who ruled for 106 years between 1283 and 1389. (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 195): But the 15th century Rakhine Minthami Eigyin says no native Arakense kings ruled for 24 years.

- This is another case of Burmese numerals ၂ (2) and ၅ (5) being miscopied: Main chronicles (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 410–413) say Saw Mon died in 742 ME (1380/81). But Mani Yadanabon (Mani Yadanabon 2009: 62) says he died in 745 ME (1383/84).

- According to the British historian GE Harvey (Harvey 1925: 86), the nominee was Swa's his own son by the daughter of Minister Min Yaza. But the chronicles (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 414–415) do not list Saw Me as a son; they mention him as a long-time loyal servant of Swa. Moreover, according to the chronicles, Swa met Yaza only in 1368/69 (730 ME). Even if Swa had married Yaza's daughter in 1368, their son would only be about 11 years old in 1380.

- (Htin Aung 1967: 87): Chinese records claim that Swa sought help from Ming China, and that he was given recognition as King of Ava. But Burmese chronicles make no mention of such a request.

- (Than Tun 1959: 128): A contemporary inscription says the earthquake took place on Thursday, 4th waxing of Pyatho 734 ME, which translates to Sunday, 28 November 1372 using the standard ME-to-CE calendar translator by the Universities Research Center in Myanmar and Than Tun. But per (Eades 1989: 82) 734 ME was a great intercalary year. It means Thursday, 4th waxing of Pyatho 734 ME = Thursday, 30 December 1372.

- December 1385 per (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 195−197), which says the invasion began in 747 ME, as Tarabya was about to turn 17 (enter his 18th year). But the standard chronicles (Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 290−293) and (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 417−420) say the invasion took place in 1386−87. But the chronicle Razadarit Ayedawbon (Pan Hla 2005: 164) suggests that the invasion took place in the dry season following Razadarit's accession, 1384–85.

- According to Razadarit Ayedawbon (Pan Hla 2005: 197), the invasion took place two years later in 1392−93. But according to the standard Burmese chronicles, the Ava forces were fighting the Maw Shans in 1392−93.

- Standard chronicles (Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 304) and (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 435–436) say he died in Nadaw 762 ME (17 November 1400 to 15 December 1400) in his 70th year (i.e. age 69); he was succeeded by Tarabya, who ruled for seven months; Tarabya in turn was succeeded by Minkhaung I. Per (Than Tun 1959: 128), inscriptional evidence shows that Minkhaung I became king on 9th waxing of Nadaw 762 ME (25 November 1400), which means that the chronicle reported date of death of Swa is actually the date of death of Tarabya, and that Swa had died earlier. While the main chronicles say that he died 7 months earlier, other chronicles (Zata 1960: 46, 72) and (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 206−207) say Tarabya ruled for 5 months. (Mani Yadanabon 2013: 65) says Tarabya ruled for 5 months and 7 days.

- (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 405) says Swa appointed Sithu as governor of Pagan in 1368. Per (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 430), Uzana III, governor of Pagan, commanded a flotilla in the 1390–91 campaign against Pegu. Uzana III may also have been the unnamed governor of Pagan who commanded a regiment in the 1385–86 campaign per (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 418).

- Chronicles do not say the name of Lord of Pinle who died in 1386 per (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 418). Per (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 380) Min Letwe was governor of Pinle at the end of Pinya.

- (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 206) cites a 1401 inscription by Queen Shin Saw Gyi which says that she was "Hsinbyushin Me" (ဆင်ဖြူရှင်မယ်), which Yazawin Thit takes to be "mother of Lord of the White Elephant (Tarabya)". (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 206, footnote 3) and (Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 435): Hmannan rejects Yazawin Thit's correction, saying that the term "Hsinbyushin Me" could also mean a title "Lady Lord of the White Elephant", and that all the prior chronicles say Tarabya's mother was Khame Mi. However, the main chronicles' also say that Tarabya was born c. 1369, and the eldest child of Khame Mi. This means Khame Mi had her first child in her late 30s before having four other children—quite unlikely. On the other hand, Shin Saw Gyi, born in the late 1340s, would still be about 20 when Tarabya was born in 1368.

- (Zata 1960: 72): Monday, 1st nekkhat of Wagaung 763 ME = Friday, 5 July 1331 [sic]. He became king in his 36th year (age 35). All other major chronicles including Zata's own List of Ava Kings section say he became king in his 37th year (age 36).

References

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 402–403

- Sandamala Linkara Vol. 1 1999: 180–181

- Htin Aung 1967: 86

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 384

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 380

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 384–385

- Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 280

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 393–394

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 396, 398

- Harvey 1925: 80–81

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 401

- Than Tun 1959: 128

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 405

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 404

- Htin Aung 1967: 87−88

- Than Tun 1959: 124

- Pan Hla 2005: 57

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 408

- Pan Hla 2005: 59−60

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 408−409

- Harvey 1925: 85–86

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 409

- Than Tun 1959: 131

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 414–415

- Mani Yadanabon 2009: 63

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 413

- Sein Lwin Lay 2006: 23

- Htin Aung 1967: 87

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 414

- Hmannan Vol. 2 2003: 164

- Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 335

- Than Tun 1959: 129

- Sein Lwin Lay 2006: 24

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 435

- Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 290−293

- Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 195−197

- Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 295−297

- Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 198−199

- Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 199−200

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 424

- Pan Hla 2005: 171–175

- Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 299

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 427

- Pan Hla 2005: 189−190

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 429

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 431

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 432

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 433

- Harvey 1925: 85

- Aung-Thwin and Aung-Thwin 2012: 109

- Lieberman 2003: 35

- Aung-Thwin 1985: 99–101

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 382

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 400

- Zata 1960: 46

- Maha Yazawin Vol. 1 2006: 279, 304

- Mani Yadanabon 2009: 35

- Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 184, 206−207

- Hmannan Vol. 1 2003: 402, 435−436

Bibliography

- Aung-Thwin, Michael (1985). Pagan: The Origins of Modern Burma. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 0-8248-0960-2.

- Aung-Thwin, Michael A.; Maitrii Aung-Thwin (2012). A History of Myanmar Since Ancient Times (illustrated ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-1-86189-901-9.

- Eade, J.C. (1989). Southeast Asian Ephemeris: Solar and Planetary Positions, A.D. 638–2000. Ithaca: Cornell University. ISBN 0-87727-704-4.

- Fernquest, Jon (Spring 2006). "Rajadhirat's Mask of Command: Military Leadership in Burma (c. 1348–1421)" (PDF). SBBR. 4 (1).

- Hall, D.G.E. (1960). Burma (2013 ed.). Read Books. p. 204. ISBN 9781447487906.

- Harvey, G. E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Htin Aung, Maung (1967). A History of Burma. New York and London: Cambridge University Press.

- Kala, U (1724). Maha Yazawin (in Burmese). 1–3 (2006, 4th printing ed.). Yangon: Ya-Pyei Publishing.

- Lieberman, Victor B. (2003). Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830, volume 1, Integration on the Mainland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80496-7.

- Maha Sithu (2012) [1798]. Kyaw Win; Thein Hlaing (eds.). Yazawin Thit (in Burmese). 1–3 (2nd ed.). Yangon: Ya-Pyei Publishing.

- Royal Historians of Burma (c. 1680). U Hla Tin (Hla Thamein) (ed.). Zatadawbon Yazawin (1960 ed.). Historical Research Directorate of the Union of Burma.

- Royal Historical Commission of Burma (1832). Hmannan Yazawin (in Burmese). 1–3 (2003 ed.). Yangon: Ministry of Information, Myanmar.

- Sandalinka, Shin (1781). Mani Yadanabon (in Burmese) (2009, 4th printing ed.). Yangon: Seit-Ku Cho Cho.

- Sandamala Linkara, Ashin (1931). Rakhine Razawin Thit (in Burmese). 1–2 (1997–1999 ed.). Yangon: Tetlan Sarpay.

- Sein Lwin Lay, Kahtika U (1968). Min Taya Shwe Hti and Bayinnaung: Ketumadi Taungoo Yazawin (in Burmese) (2006, 2nd printing ed.). Yangon: Yan Aung Sarpay.

- Taw, Sein Ko; Emanuel Forchhammer (1899). Inscriptions of Pagan, Pinya and Ava: Translation, with Notes. Archaeological Survey of India.

- Than Tun (December 1959). "History of Burma: A.D. 1300–1400". Journal of Burma Research Society. XLII (II).

Swa Saw Ke Ava Kingdom Born: 16 July 1330 Died: April 1400 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Thado Minbya |

King of Ava 5 September 1367 – c. April 1400 |

Succeeded by Tarabya |

| Royal titles | ||

| Preceded by |

Governor of Amyint 1351–67 |

Succeeded by Tuyin Theinzi |

| Preceded by Thihapate of Yamethin |

Governor of Yamethin 1351 |

Succeeded by Thilawa of Yamethin |

| Preceded by |

Governor of Talok c. 1344–51 |

Succeeded by Yazathu |