Thibaw Min

Thibaw Min, also Thebaw or Theebaw (Burmese: သီပေါမင်း, pronounced [θìbɔ́ mɪ́ɰ̃]; 1 January 1859 – 19 December 1916) was the last king of the Konbaung Dynasty of Burma (Myanmar) and also the last Burmese sovereign in the country's history. His reign ended when Burma was defeated by the forces of the British Empire in the Third Anglo-Burmese War, on 29 November 1885, prior to its official annexation on 1 January 1886.

| Thibaw သီပေါမင်း | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Thibaw c. 1880 | |||||

| King of Burma Prince of Thibaw | |||||

| Reign | 1 October 1878 – 29 November 1885 | ||||

| Coronation | 6 November 1878 | ||||

| Predecessor | Mindon Min | ||||

| Successor | Queen Victoria as the Empress of India | ||||

| Prime Minister | Kinwun Mingyi U Kaung | ||||

| Born | Maung Pu (မောင်ပု) 1 January 1859 Saturday, 12th waning of Nadaw 1220 ME[1] Mandalay, Konbaung Burma | ||||

| Died | 19 December 1916 (aged 57) Tuesday, 10th waning of Nadaw 1278 ME Ratnagiri, Bombay State, British India | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | Supayalat | ||||

| Issue Detail | 2 sons, 6 daughters, including: Myat Phaya Gyi Myat Phaya Lat Myat Phaya Myat Phaya Galay | ||||

| |||||

| House | Konbaung | ||||

| Father | Mindon Min | ||||

| Mother | Laungshe Mibaya | ||||

| Religion | Theravada Buddhism | ||||

Early life

Prince Thibaw was born Maung Pu (မောင်ပု), the son of King Mindon and one of his consorts, Laungshe Mibaya. Thibaw's mother had been banished from the palace court by Mindon and spent her final years as a thilashin, a kind of female Burmese Buddhist renunciant. During the early years of his life, Thibaw studied Buddhist texts at a kyaung to win his father's favor. He passed the Pahtamabyan religious examinations and gained respect and recognition from his father and the chief queen.

One of Mindon's chief consorts, the Queen of the Middle Palace, Hsinbyumashin, helped to broker a marriage between her second daughter, Supayalat and Thibaw, who were half-siblings by blood.

Accession

In 1878, Thibaw succeeded his father in a bloody succession massacre. Hsinbyumashin, one of Mindon's queens, had grown dominant at the Mandalay court during Mindon's final days. Under the guise that Mindon wanted to bid his children (other princes and princesses) farewell, Hsinbyumashin had all royals of close age (who could potentially be heir to the throne) mercilessly slaughtered by edict, to ensure that Thibaw and her daughter Supayalat would assume the throne.

At the time of his accession, Lower Burma, half of the kingdom's former territory, had been under British occupation for thirty years and it was no secret that the King intended to regain this territory. Relations had soured during the early 1880s when the King was perceived as having made moves to align his country with the French more closely. Relations deteriorated further in an incident later called "The Great Shoe Question", where visiting British dignitaries refused to remove their shoes before entering the royal palace and were subsequently banished.

At the time, the kingdom's treasury reserves had diminished, forcing the government to increase taxation on the peasants. In 1878, the national lottery was also introduced on a trial basis, which became popular but soon went awry, with many families losing their livelihoods.[2] The lottery experiment was ended in 1880.[2]

In October to November 1878, a meeting at Mandalay Palace's North Garden significantly expanded the size of the Hluttaw from four departments to 14:

- Agriculture

- Public works

- Land warfare

- Taxation

- Religious knowledge

- Royal estate management

- Sassamedha (Personal taxes)

- Criminal justice

- Civil justice

- Water-borne warfare

- Foreign affairs

- Partnerships

- Town and village affairs

- Mechanised industries

During King Thibaw's reign, a new administrative unit, the district (ခရိုင်, khayaing), based on the administrative units of British India, was created, in order to centralize administration from the court. Altogether, the kingdom was divided into 10 districts and administrated by district ministers (ခရိုင်ဝန်), who had authority over smaller administrative units, the villages and towns.[2] Thibaw also rolled back the conversion of local administrators from myothugyi (မြို့သူကြီး) to myook (မြို့အုတ်), which had been part of administrative reforms carried out by Mindon, based on the prevailing administrative system in Lower Burma.[3]

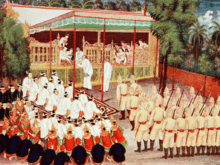

A proclamation issued by the court of King Thibaw in 1885 which called on his countrymen to liberate Lower Burma was used by the British as pretext that he was a tyrant who reneged on his treaties and they decided to complete the conquest they had started in 1824. The invasion force which consisted of 11,000 men, a fleet of flat-bottomed boats and elephant batteries, was led by General Harry Prendergast.

Abdication

British troops quickly reached the royal capital of Mandalay with little opposition. Within twenty-four hours, the troops had marched to the Mandalay Palace to demand the unconditional surrender of Thibaw and his kingdom within twenty-four hours.[4] At the time, the king and queen had retired to a summer house in the palace gardens.

The following morning, King Thibaw was forced on a bullock cart, along with his family, and proceeded to a steamer on the Irrawaddy River, in the presence of a huge crowd of subjects.[4]

According to some accounts, Thibaw begged for his life to be saved before being exiled:[4]

Here a guard of British soldiers was drawn up: they presented arms on the appearance of the royal prisoners. As their bayonets flashed in the sunlight, the king fell on his knees in abject terror. "They will kill me," he cried wildly. "Save my life." His queen was braver. She strode on erect — her little child clinging to her dress — fierce and dauntless to the last. So the king and queen of Burma were exiled."

Life in exile

After abdicating the throne, Thibaw, his wife Supayalat and two infant daughters were exiled to Ratnagiri, India, a port city off the Arabian Sea. During their first five years in India, Thibaw's family lived at Sir James Outram's bungalow in Dharangaon, inland from Ratanagiri, while an official residence was being built.[5] The family then moved into a two storey brick building, colloquially "Thibaw's Palace," built of laterite and lava rock, on a 20 acres (8.1 ha) property.[5]

For his first five years at Ratanagiri, Thibaw received a monthly government pension of 100,000 rupees ($30,000).[5] In subsequent years, his pension was halved; at his death, his pension was 25,000 rupees.[5] He was reportedly reclusive and did not leave the property during his time in Ratanagiri, although Thibaw financed and sponsored local festivals, particularly during Diwali.[5] He died at age 57 on 15 December 1916 and was buried at a small walled plot adjacent to a Christian cemetery, along with one of his consorts, Hteiksu Phaya Galay.[5]

The surviving exiled royal family were relocated to Burma in 1919 after the kings death. The first born daughter, Myat Phaya Gyi, returned to Ratnagiri despite the royal family’s opposition. She had a romance with the indian driver, Gopal Sawant, during exile which had resulted in a daughter, Tutu. Gyi and Tutu lived in poverty and survived by making paper flowers to sell on the markets because Sawant took all of her pension from the british government, he did however buy them a house. Tutu went on to live in poverty and had 11 children who never knew their past until recent interests in the royal family. The second daughter, Myat Phaya Lat, became the pretender to the throne and married her fathers private secretary, Khin Maung Lat, who also was his nephew. They did not have any children but Lat adopted her nepalese maidservants son. The third daughter, Myat Phaya, went on to marry twice. Her first marriage was to a burmese prince, Hteik Tin Kodawgyi, whom she had a daughter with, Phaya Rita, and after their divorce she got remarried with a burmese lawyer, Mya U. Phaya Rita married her cousin, Taw Phaya, son of Myat Phaya Galay. The fourth daughter, Myat Phaya Galay, married a former burmese monk, Ko Ko Naing, and had six children one of whom was pretender to the throne, Taw Phaya, who married his cousin, Phaya Rita, daughter of Myat Phaya. Both the third and fourth daughter were born in India but died in Burma and two of their children married each other, pretender to the throne Taw Phaya and princess Phaya Rita, they had seven children thus securing the true royal family line.

Renewed interest

In December 2012, the president of Burma Thein Sein paid homage at the run-down tomb of the King in the western Indian coastal city of Ratnagiri and met the late monarch’s descendants. He was the first head of Burmese government to visit the grave.[6]

Family

- Parents:

- Consorts and children:

- Supayalat

- Myat Phaya Gyi

- Myat Phaya Lat

- Myat Phaya

- Myat Phaya Galay

- 2 sons (unnamed)

- Supayagyi

See also

- Konbaung dynasty

- France-Burma relations

References

- Konbaung Set Vol. 3 2004: 475

- Thant Myint-U (2001). The Making Of Modern Burma. Cambridge University Press. p. 9780521799140.

- J. George Scott, ed. (1901). Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States. 1. Rangoon: Government of Burma.

- Synge, M.B. (1911). "Annexation of Burma". Growth of the British Empire.

- Christian, John LeRoy (1944). "Thebaw: Last King of Burma". The Journal of Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies: 309–312. doi:10.2307/2049030.

- Thein Sein visits grave of Burma’s last king. Retrieved 2012-12-26.

- The Baldwin Project: Growth of the British Empire by M. B. Synge at www.mainlesson.com

- Political Topics And Discussion > Who Really Killed General Aung San? at www.bearpit.net

Bibliography

- Candier, Aurore (December 2011). "Conjuncture and Reform in the Late Konbaung Period". Journal of Burma Studies 15 (2).

- Charney, Michael W. (2006). Powerful Learning: Buddhist Literati and the Throne in Burma's Last Dynasty, 1752–1885. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

- Hall, D.G.E. (1960). Burma (3rd ed.). Hutchinson University Library. ISBN 978-1406735031.

- Htin Aung, Maung (1967). A History of Burma. New York and London: Cambridge University Press.

- Maung Maung Tin, U (1905). Konbaung Set Yazawin (in Burmese). 1–3 (2004 ed.). Yangon: Department of Universities History Research, University of Yangon.

- Myint-U, Thant (2006). The River of Lost Footsteps—Histories of Burma. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-16342-6.

- Myint-U, Thant (2001). The Making Of Modern Burma. Cambridge University Press. pp. 9780521799140.

- Scott, J. George, ed. (1901). Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States. 1. Rangoon: Government of Burma.

- Phayre, Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur P. (1883). History of Burma (1967 ed.). London: Susil Gupta.

Links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thibaw Min. |

Thibaw Min Konbaung Dynasty Born: 1 January 1859 Died: 19 December 1916 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Mindon |

King of Burma 1 October 1878 – 29 November 1885 |

Succeeded by Burmese monarchy abolished |

| Royal titles | ||

| Preceded by Kanaung |

Heir to the Burmese Throne as Prince of Thibaw 19 September 1878 – 1 October 1878 |

Succeeded by Myat Phaya Lat (Presumed) |