Suessiones

The Suessiones were a Belgic tribe, dwelling in the modern Aisne and Oise regions during the La Tène and Roman periods.[1][2]

During the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC), their oppidum Noviodunum (Pommiers) was besieged and conquered by Caesar. Following their defeat by the Romans at the end of the campaign of 57 BC, they fell into dependence upon Rome and remained faithful to the Romans during the revolt of 51 BC.[3]

Name

Attestations

They are mentioned as Suessiones by Caesar (mid-1st c. BC) and Pliny (1st c. AD),[4][5] as Souessíōnes (Σουεσσίωνες) and Ou̓essíōnas (Οὐεσσίωνας) by Strabo (early 1st c. AD),[6] and as Ouéssones (Οὐέσσονες) by Ptolemy (2nd c. AD).[7][8]

Etymology

The etymology of the name Suessiones is uncertain. It could stem from Gaulish suexs ('six'; compare with Welsh chwech), following a custom of using numbers in tribal names among Gauls (e.g., Vo-corii, Tri-corii, Petru-corii).[9][10] Other proposed etymologies include *su-ed-ti-ones ('rich in food'), or a formation from the root *swe- ('proper, to oneself').[9] The tribal name Suessetani, attested in Iberia, could be linguistically related.[10]

The city of Soissons, attested as Augusta Suessionum in the 4th c. AD (Suessio in 561, Soisson in 1288), and the region of Soissonnais, are named after the tribe.[11]

Geography

Territory

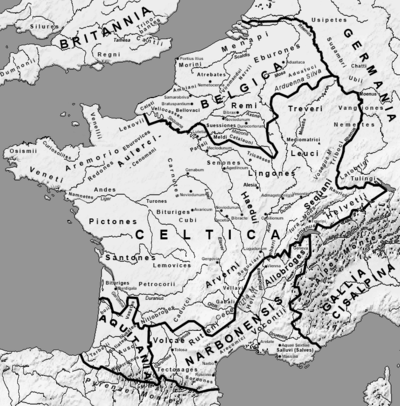

The territory of the Suessiones was bordered by the forest of the Oise valley to the west, and by wooded heights along the Marne river (near Épernay) to the southeast.[1] They dwelled northeast of the smaller Meldi and Silvanectes, and west of the Remi.[1][2]

Settlements

La Tène period

The oppidum of Villeneuve-Saint-Germain, founded on a plain near the Aisne river in the middle of the 1st century BC, was the main settlement of the Suessiones before the Roman conquest.[12][13] It was an important Gallic agglomeration, reaching 70ha at its height.[12]

From the period of the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC), their chief town became the oppidum of Pommiers, generally identified with the fortress of Noviodunum (Gaulish: 'new fortress') mentioned by Caesar.[14][13] Pommiers was progressively abandoned and became unoccupied after the end of reign of Augustus (27 BC–14 AD), when their chief town became Augusta Suessionum.[15]

Smaller oppida were also located at Ambleny, Pont-Saint-Mard, or Epagny.[13]

Roman period

Augusta Suessionum (modern Soissons), founded ca. 20 BC on an area more adapted to urbanization than Villeneuve-Saint-Germain and Pommiers, became the capital of the civitas Suessionum during the Roman period.[12] Reaching 100–120ha at its height, it was one of most important settlements of northwestern Gaul.[16] The Germanic Migrations in the 3rd century AD led to the erection of fortifications in the city. Rome was only able to defend the region until the defeat of Syagrius against the Frankish king Clovis in 486.[12]

Smaller agglomerations within the civitas were also located at Château-Thierry, Ciry-Salsogne, Épaux-Bézu, Blesmes, Sinceny, and Ressons-le-Long.[17]

History

La Tène period

According to archaeologist Jean-Louis Brunaux, large-scale migrations occurred in the northern part of Gaul in the late 4th–early 3rd century BC, which may correspond to the coming of the Belgae. Those cultural changes emerged later among the Suessiones, who were probably culturally integrated to the Belgae only after the 3rd century. New funerary customs (from burial to cremation) are noticeable by 250–200 BC on the territories of the Ambi or Bellovaci, whereas incineration occurred later in the Aisne valley from 200–150.[18]

Around 80 BC, the Suessones king Diviciacus gained supremacy in areas of southeastern Britain.[2]

Gallic Wars

Caesar recounts in his Gallic Wars that in 57 BC the Suessiones were ruled by Galba.[19]

Political organization

Until the Gallic Wars (58–50 BC), the Suessiones shared a common cultural identity with the neighbouring Remi, which with they were linked by the same law, the same magistrates and a unified commander-in-chief.[2] In reality, this virtual state of union between the two tribes probably leaned in favour of the Suessiones. The Remi asked the protection of the Romans by the time Caesar entered Gallia Belgica in 57 BC, thus gaining independence from a possibly asymmetrical relationship.[1][3] The Meldi were also probably tributary to the more powerful Suessiones.[1]

During the Roman period, the Suessiones were regarded as dependant upon Rome, whereas the Remi were considered the allies of the Romans. Parts of the Suessionean territory were given to the Remi, the Meldi, and perhaps to the Sulbanectes. The dependency of the Suessiones upon the Remi appears to have lasted until the beginning of the 1st century AD, and a Roman military presence is attested in Suessionean territory at the camp of Arlaines (Ressons-le-Long) until the Flavian period.[20]

Religion

In Augusta Suessionum were found a votive stele dedicated to the native goddess Camuloriga (Camloriga), and a statuette of the Roman god Mercury.[21] The divine name Camuloriga stems from of the Gaulish term camulos, possibly translated as 'champion, servant' (denoting one who makes efforts) and attached to the suffix -riga- (< rigani 'queen'; compare with Old Irish rígain 'queen').[22][23]

Rural sanctuaries have been identified at Fossoy, Grand-Rozoy, and Pasly. Archaeologists have not been able to identified which deities were worshipped there.[21]

Economy

The Suessiones straddled two river routes, the Aisne and the Marne.[1] Coinage minted by Belgic Gauls first appeared in Britain in the mid-2nd century BC with the coinage now categorized as the "Gallo-Belgic A" type.[24] Coins associated with King Diviciacus of the Suessiones, issued near or between 90 and 60 BC, have been categorized as "Gallo-Belgic C." Finds of this issue of coin extend from Sussex to the Wash, with a concentration of finds near Kent. A later issue of coin, "Gallo-Belgic F" (c. 60-50 BC), has concentrated finds near Paris, throughout the lands of the Suessiones, and the southern, coastal areas of Britain. These finds lead scholars to suggest that the Suessiones had significant trade and migration into Britain during the 2nd and 1st centuries prior to Roman conquest.[25] Caesar describes the Belgae as going to Britain looking for booty: "The inland part of Britain is inhabited by tribes declared in their own tradition to be indigenous to the island, the maritime part by tribes that migrated at an earlier time from Belgium to seek booty by invasion."[26]

See also

- List of peoples of Gaul

- List of Celtic tribes

References

- Wightman 1985, p. 27.

- Schön 2006.

- Pichon 2002, p. 78.

- Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, 2:3

- Pliny. Naturalis Historia, 4:6

- Strabo. Geōgraphiká, 4:3:5; 4:4:3

- Ptolemy. Geōgraphikḕ Hyphḗgēsis, 2:9:6

- Falileyev 2010, p. entry 2356.

- Delamarre 2003, p. 285.

- Busse 2006, p. 199.

- Nègre 1990, p. 157.

- Roussel 1999, p. 129.

- Pichon 2002, p. 76.

- Brun 2002, p. 307.

- Pichon 2002, p. 80.

- Pichon 2002, p. 81.

- Pichon 2002, p. 82.

- Pichon 2002, p. 74.

- Gaius Julius Caesar (57 BC), Commentarii de Bello Gallico, II:4.

- Pichon 2002, pp. 78–79.

- Pichon 2002, p. 84.

- Delamarre 2003, p. 101.

- Lindsay 1961, p. 732.

- "Gold stater ('Gallo-Belgic A' type)". British Museum. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- Togodumnus (2011). "The Celtic Tribes of Britain: The Belgae". www.Roman-Britain.org. Retrieved 2015-04-16.

- Gaius Julius Caesar (57 BC), Commentarii de Bello Gallico, V:12.

Bibliography

- Brun, Patrice (2002). "Territoires et agglomérations chez les Suessiones". Territoires Celtiques: Espaces ethniques et territoires des agglomérations protohistoriques d'Europe occidentale. Actes du XXIVe colloque international de I'AFEAF. Martigues, 1-4 juin 2000. Errance.

- Busse, Peter E. (2006). "Belgae". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 195–200. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental (in French). Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Falileyev, Alexander (2010). Dictionary of Continental Celtic Place-names: A Celtic Companion to the Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. CMCS. ISBN 978-0955718236.

- Lindsay, Jack (1961). "Camulos and Belenos". Latomus. 20 (4): 731–743. ISSN 0023-8856. JSTOR 41522086.

- Nègre, Ernest (1990). Toponymie générale de la France (in French). Librairie Droz. ISBN 978-2-600-02883-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pichon, Blaise (2002). Carte archéologique de la Gaule: 02. Aisne (in French). Les Editions de la MSH. ISBN 978-2-87754-081-0.

- Roussel, Dominique (1999). "Soissons". Revue archéologique de Picardie. 16 (1): 129–137. doi:10.3406/pica.1999.2053.

- Schön, Franz (2006). "Suessiones". Brill's New Pauly.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wightman, Edith M. (1985). Gallia Belgica. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05297-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Debord, Jean. Un statère anépigraphe des Suessiones découvert à Berzy-le-Sec (Aisne). In: Revue archéologique de Picardie, n°1-2, 1985. pp. 21–24. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/pica.1985.1458] ; www.persee.fr/doc/pica_0752-5656_1985_num_1_1_1458