Straw Dogs (1971 film)

Straw Dogs is a 1971 psychological thriller film directed by Sam Peckinpah and starring Dustin Hoffman and Susan George. The screenplay, by Peckinpah and David Zelag Goodman, is based upon Gordon M. Williams's 1969 novel, The Siege of Trencher's Farm. The film's title derives from a discussion in the Tao Te Ching that likens people to the ancient Chinese ceremonial straw dog, being of ceremonial worth, but afterwards discarded with indifference.

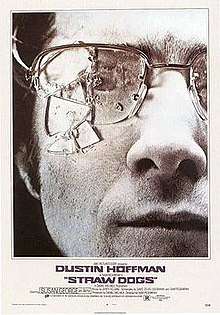

| Straw Dogs | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sam Peckinpah |

| Produced by | Daniel Melnick |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Siege of Trencher's Farm by Gordon M. Williams |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Jerry Fielding |

| Cinematography | John Coquillon |

| Edited by |

|

Production company |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 117 minutes[3] 113 minutes[4] (Edited cut) |

| Country | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.2 million[5] |

| Box office | $8 million (rentals)[5] |

The film is noted for its violent concluding sequences and two complicated rape scenes, which were subject to censorship by numerous film rating boards. Released theatrically in the same year as A Clockwork Orange, The French Connection, and Dirty Harry, the film sparked heated controversy over a perceived increase of violence in films generally.[6][7]

The film premiered in the UK in November 1971. Although controversial at the time, Straw Dogs is considered by some critics to be one of Peckinpah's greatest films.[8] A remake directed by Rod Lurie and starring James Marsden and Kate Bosworth was released on September 16, 2011.

Plot

After securing a grant to study stellar structures, American applied mathematician David Sumner moves with his glamorous young English wife Amy to her home village of Wakely in the Cornish countryside. Amy's ex-boyfriend Charlie Venner, along with his cronies Norman Scutt, Chris Cawsey, and Phil Riddaway, immediately resent that the meek outsider has married one of their own. Scutt, a former convict, confides in Cawsey of his jealousy of Venner's past relationship with Amy. David meets Venner's uncle, Tom Hedden, a violent drunkard whose flirtatious teenage daughter Janice seems attracted to Henry Niles, a mentally deficient man despised by the entire town.

The Sumners have taken an isolated farmhouse, Trenchers Farm, that once belonged to Amy's father, and still contains his furniture. They hire Scutt and Cawsey to re-roof its garage, and when impatient with lack of progress add Venner and his cousin Bobby. Tensions in their marriage soon become apparent. Amy criticizes David's condescension towards her and his escape from the volatile, politicized campus, suggesting that cowardice was his true reason for leaving America. He responds by withdrawing deeper into his studies, ignoring both the hostility of the locals and Amy's dissatisfaction. His aloofness results in Amy's attention-gathering pranks and provocative demeanor towards the workmen, particularly Venner. David even struggles to be accepted by the educated locals, as shown in conversation with the vicar, Reverend Barney Hood, and the local magistrate, Major John Scott.

When David finds their missing cat hanging dead in their bedroom closet, Amy reckons Cawsey or Scutt is responsible. She presses David to confront the workmen, but he is too intimidated to accuse them. The men invite David to go hunting the following day. They take him to a remote location and leave him there with the promise of driving birds towards him. With David away, Venner goes to Trenchers Farm where he attempts to initiate sex with Amy. She resists at first, then submits. After, Norman Scutt enters silently, motions Venner to move away at gunpoint and rapes Amy while Venner reluctantly holds her down. David returns much later, smarting from the practical joke the men pulled on him. Amy, though clearly upset, says nothing about the intruders and what they did to her, apart from a cryptic comment that escapes his attention.

The next day, David fires the workmen, ostensibly for their slow progress. Later, the Sumners attend a church social where Amy becomes distraught on seeing her rapists. They leave the social early, driving through thick fog, and accidentally hit Henry Niles. They take him to their home and David phones the local pub to report the accident, not knowing that Niles had just killed Janice, strangling her in a panic when she tried to seduce him. Hedden, now searching for her, learns that she was last seen with Niles, and from David's phone call is alerted to Niles's whereabouts. Soon, Hedden, Scutt, Venner, Cawsey and Riddaway are drunkenly pounding on the Sumners' door. Inferring their intention to lynch Niles, David refuses to let them take him despite Amy's pleas. The standoff seems to unlock a territorial instinct in David: "I will not allow violence against this house."

Major Scott arrives to defuse the situation, but is accidentally shot dead by Hedden during a struggle. Realizing the danger in witnessing this homicide, David improvises various makeshift traps and weapons, including boiling oil, to fend off the siege. David inadvertently forces Hedden to shoot his own foot, knocks Riddaway temporarily unconscious and bludgeons Cawsey to death with a poker. Venner holds him at gunpoint, but Amy's screams alert both men when Scutt assaults her. Scutt suggests Venner join him in another gang rape, but Venner shoots him dead. David disarms Venner and in the ensuing fight snaps an ornamental mantrap around Venner's neck, killing him. Watching the mayhem around him and surprised by his own violence, David mutters to himself, "Jesus, I got 'em all." An awakened Riddaway then brutally attacks him, but is shot by Amy as he tries to break David's spine.

David gets into his car to drive Niles back to the village. Niles says he does not know his way home. David says he does not either.

Cast

- Dustin Hoffman as David Sumner

- Susan George as Amy Sumner

- Peter Vaughan as Tom Hedden

- T. P. McKenna as Major John Scott

- Del Henney as Charlie Venner

- Jim Norton as Chris Cawsey

- Donald Webster as Phil Riddaway

- Ken Hutchison as Norman Scutt

- Len Jones as Bobby Hedden

- Sally Thomsett as Janice Hedden

- Robert Keegan as Harry Ware

- Peter Arne as John Niles

- Colin Welland as Reverend Barney Hood

- Cherina Schaer as Louise Hood

- David Warner as Henry Niles (uncredited)[9]

- Michael Mundell as Bertie Hedden (uncredited)

- June Brown as Mrs Hedden (scenes deleted)

- Chloe Franks as Emma Hedden (scenes deleted)

Production

Sam Peckinpah's two previous films, The Wild Bunch and The Ballad of Cable Hogue, had been made for Warner Bros.-Seven Arts. His connection with the company ended after the chaotic filming of Cable Hogue wrapped 19 days over schedule and $3 million over budget (equivalent to $15 million in 2018).[10] Left with a limited number of directing jobs, Peckinpah was forced to travel to England to direct Straw Dogs. Produced by Daniel Melnick, who had previously worked with Peckinpah on his 1966 television film Noon Wine, the screenplay began from Gordon Williams' novel The Siege of Trencher's Farm,[11] with Peckinpah saying "David Goodman and I sat down and tried to make something of validity out of this rotten book. We did. The only thing we kept was the siege itself".[12]

Beau Bridges, Stacy Keach, Sidney Poitier, Jack Nicholson, and Donald Sutherland were considered for the lead role of David Sumner before Dustin Hoffman was cast.[13] Hoffman agreed to do the film because he was intrigued by the character, a pacifist unaware of his feelings and potential for violence that were the same feelings he abhorred in society.[14] Judy Geeson, Jacqueline Bisset, Diana Rigg, Helen Mirren, Carol White, Charlotte Rampling, and Hayley Mills were considered for the role of Amy before Susan George was finally selected.[15] Hoffman disagreed with the casting, as he felt his character would never marry such a "Lolita-ish" kind of girl. Peckinpah insisted on George, a relatively unknown actress in the US at that time.[16]

Location shooting took place around St Buryan near Penzance in Cornwall, including at St Buryan's Church. Interiors were shot at Twickenham Studios in London.[17] The film's production design was by Ray Simm.

Reception

Box office

The film earned rentals of $4.5 million in North America and $3.5 million in other countries. By 1973 it had recorded an overall profit of $1,425,000.[5]

Critical response

Roger Ebert of The Chicago Sun-Times rated it 2/4 stars and described the film as "a major disappointment in which Peckinpah's theories about violence seem to have regressed to a sort of 19th-Century mixture of Kipling and machismo."[18] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called it "a special disappointment" that is "an intelligent movie, but interesting only in the context of his other works."[19] Variety wrote, "The script (from Gordon M. Williams' novel The Siege of Trencher's Farm) relies on shock and violence to tide it over weakness in development, shallow characterization and lack of motivation."[20] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post wrote, "People who are sensitive to both the sight and the implications of violence will probably be disgusted and angered by 'Straw Dogs' because there is no credible motivation for the violence. For the first time Peckinpah really seems to be specializing in violence rather than exploring its effects and meanings ... I would have walked out of 'Straw Dogs' at several points if I'd been anything but a professional critic."[21]

Other reviews were positive. Paul D. Zimmerman of Newsweek stated, "It is hard to imagine that Sam Peckinpah will ever make a better movie than Straw Dogs. It flawlessly expresses his primitive vision of violence — his belief that manhood requires rites of violence, that home and hearth are inviolate and must be defended by blood, that a man must conquer other men to prove his courage and hold on to his woman."[22] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film 3 out of 4 stars and wrote that even though he disagreed with Peckinpah's apparent worldview that "Man is an animal, and his passion for destroying his own kind lies just beneath his skin," it was nevertheless "a superbly made movie. Peckinpah creates a mood of impending violence with great skill."[23] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it "an overpowering piece of storytelling, certain to remind every viewer of the wells of primal emotion lurking within himself, beneath the fragile veneer of civilized control. It is, I think, a better picture than 'The Wild Bunch,' less ritualistic and less appallingly graphic in its violence, and in fact less cynical."[24]

Among later assessments, Entertainment Weekly in 1997 wrote that the contemporary interpretation was that of a "serious exploration of humanity's ambivalent relationship with the dark side", but it now seems an "exploitation bloodbath".[25] Nick Schager of Slant Magazine rated it 4/4 stars and wrote, "Sitting through Peckinpah's controversial classic is not unlike watching a lit fuse make its slow, inexorable way toward its combustible destination—the taut build-up is as shocking and vicious as its fiery conclusion is inevitable."[26] Philip Martin of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette wrote, "Peckinpah's Straw Dogs is a movie that has remained important to me for 40 years. Along with Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, Straw Dogs stands as a transgressively violent, deeply '70s film; one that still retains its power to shock after all these years."[27] Rotten Tomatoes, a review aggregator, reports that 83% of 40 surveyed critics gave the film a positive review; the average rating is 8.46/10. The consensus reads: "A violent, provocative meditation on manhood, Straw Dogs is viscerally impactful -- and decidedly not for the squeamish".[28]

Controversy

The film was controversial on its 1971 release, mostly because of the prolonged rape scene that is the film's centerpiece. Critics accused Peckinpah of glamorizing and eroticising rape and of engaging in misogynistic sadism and male chauvinism,[29] especially disturbed by the scene's intended ambiguity—after initially resisting, Amy appears to enjoy parts of the first rape, kissing and holding her attacker, although she later has traumatic flashbacks. Author Melanie Williams, in her 2005 book, Secrets and Laws: Collected Essays in Law, Lives and Literature, stated, "the enactment purposely catered to entrenched appetites for desired victim behavior and reinforces rape myths".[30] Another criticism is that all the main female characters depict straight women as perverse, in that every appearance of Janice and Amy is used to highlight excessive sexuality.[31]

The violence provoked strong reactions, many critics seeing it an endorsement of violence as redemption, and the film as fascist celebration of violence and vigilantism. Others see it as anti-violence, describing the bleak ending consequent to the violence. Dustin Hoffman viewed David as deliberately, yet subconsciously, provoking the violence, his concluding homicidal rampage being the emergence of his true self; this view was not shared by director Sam Peckinpah.[6]

The village of St Buryan was used as a location for the filming with some of the locals appearing as extras. Local author Derek Tangye reports in one of his books that they were not aware of the nature of the film at the time of filming, and were most upset to discover on its release that they had been used in a film of a nature so inconsistent with their own moral values.

Censorship

The studio edited the first rape scene before releasing the film in the United States, to earn an R rating from the MPAA.[32]

In the UK, the British Board of Film Classification banned it in accordance with the newly introduced Video Recordings Act. The film had been released theatrically in the United Kingdom, with the uncut version gaining an 'X' rating in 1971 and the slightly cut US R-rated print being rated '18' in 1995. In March 1999 a partially edited print of Straw Dogs, which removed most of the second rape, was refused a video certificate when the distributor lost the rights to the film after agreeing to make the requested BBFC cuts, and the full uncut version was also rejected for video three months later on the grounds that the BBFC could not pass the uncut version so soon after rejecting a cut one.

On July 1, 2002, Straw Dogs finally was certified unedited on VHS and DVD. This version was uncut, and therefore included the second rape scene, in which in the BBFC's opinion "Amy is clearly demonstrated not to enjoy the act of violation".[33] The BBFC wrote that:

The cuts made for American distribution, which were made to reduce the duration of the sequence, therefore tended paradoxically to compound the difficulty with the first rape, leaving the audience with the impression that Amy enjoyed the experience. The Board took the view in 1999 that the pre-cut version eroticised the rape and therefore raised concerns with the Video Recordings Act about promoting harmful activity. The version considered in 2002 is substantially the original uncut version of the film, restoring much of the unambiguously unpleasant second rape. The ambiguity of the first rape is given context by the second rape, which now makes it quite clear that sexual assault is not something that Amy ultimately welcomes.

Influence

Home Alone production designer John Muto identified that film as a "kids version of Straw Dogs".[34]

Director Jacques Audiard cited Straw Dogs as the basis for his 2015 film Dheepan.[35]

See also

References

- "Straw Dogs (1971)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 2017-08-31.

- "Straw Dogs - Details". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- "STRAW DOGS (X)". British Board of Film Classification. 1971-11-03. Retrieved 2013-01-21.

- "STRAW DOGS (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 2002-09-27. Retrieved 2013-01-21.

- "ABC's 5 Years of Film Production Profits & Losses", Variety, 31 May 1973 p 3

- Simmons 1982, pp. 137–138.

- Sragow, Michael (July 29, 1999). "Eyes Opening Up". Salon.com. San Francisco, California: Salon Media Group. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- Weddle 1994, p. 12.

- Harris, Will (2017-07-26). "David Warner on Twin Peaks, Tron, Titanic, Time Bandits, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles II". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 2017-11-05.

- Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2019). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved April 6, 2019. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- Weddle 1994, pp. 391–393.

- Hayes 2008, p. 101.

- Weddle 1994, p. 403.

- Simmons 1982, p. 125.

- Weddle 1994, p. 410.

- Simmons 1982, p. 126.

- Derek Pykett. British Horror Film Locations. McFarland, 2014. p.109-111

- Ebert, Roger (December 27, 1971). "Straw Dogs". The Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago, Illinois: Sun-Times Media Group. Retrieved February 6, 2015 – via rogerebert.com.

- Canby, Vincent (January 20, 1972). "Peckinpah's 'Straw Dogs' Starring Hoffman Arrives". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Retrieved February 16, 2019.

- "Review: 'Straw Dogs'". Variety. Los Angeles California: Penske Media Corporation. December 31, 1970. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- Arnold, Gary (December 29, 1971). "A Horror Show". The Washington Post. B1, B7.

- Zimmerman, Paul D. (December 19, 1971). "Newsweek Acclaims 'Straw Dogs'". Los Angeles Times. Calendar, p. 20.

- Siskel, Gene (December 24, 1971). "Peckinpah's 'Straw Dogs'". Chicago Tribune. 15.

- Champlin, Charles (December 24, 1971). "Violence Theme of 'Straw Dogs'". Los Angeles Times. Part II, p. 2.

- "Straw Dogs". Entertainment Weekly. January 10, 1997. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- Schager, Nick (March 28, 2003). "Straw Dogs". Slant Magazine. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- Martin, Philip (September 16, 2011). "First Straw Dogs about killer within". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- "Straw Dogs (1971)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 30, 2019.

- Weddle 1994, pp. 25, 399–400, 426–428.

- Wiliams 2005, p. 71.

- Williams, Linda Ruth (February 1995). "Straw Dogs: Women can only misbehave". Sight & Sound. Vol. 5 no. 2. pp. 26, 27. ISSN 0037-4806.

- Simmons 1982, p. 137.

- "BBFC passes STRAW DOGS uncut on video". 2002-07-01. Archived from the original on 2008-08-27.

- Siegel, Alan. "Home Alone Hit Theaters 25 Years Ago. Here's How They Filmed Its Bonkers Finale". slate.com. Slate. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- Donadio, Rachel (2016-04-20). "For Its Star, 'Dheepan' Was the Role of His Lifetime". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-06-05.

Sources

- Hayes, Kevin J. (2008). Sam Peckinpah: Interviews. Jackson, Mississippi: Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-934-110645.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simmons, Garner (1982). Peckinpah, A Portrait in Montage. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-76493-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weddle, David (1994). If They Move...Kill 'Em!. New York City: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3776-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Melanie (2005). Secrets and Laws: Collected Essays Law, Lives and Literature. Abingdon, England: Psychology Press. ISBN 1-84472-018-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Straw Dogs on IMDb

- Straw Dogs at AllMovie

- Straw Dogs at Box Office Mojo

- Straw Dogs at Rotten Tomatoes

- Straw Dogs: Home Like No Place an essay by Joshua Clover at the Criterion Collection

- Essay by Michael Sragow at Salon.com